One of the interesting, and sometimes frustrating, things about learning Chinese characters is that there’s always more to learn. While it’s true that there are always things to learn about writing any language, I’m not talking about finer details of composition and style here, I’m talking about the basic units needed to write words.

One of the interesting, and sometimes frustrating, things about learning Chinese characters is that there’s always more to learn. While it’s true that there are always things to learn about writing any language, I’m not talking about finer details of composition and style here, I’m talking about the basic units needed to write words.

This is interesting, because it’s an excellent way of learning how to learn. I’ve had many opportunities to try different things and see what works and what doesn’t. But it’s also frustrating sometimes, because it literally never ends. Of course, this is partly my own fault as I insist on maintaining the ability to write the 5,000 most common characters by hand, when it would be perfectly feasible to ignore handwriting beyond the most common characters.

In this article, I will share with you seven mistakes I’ve made when reviewing characters recently, and what I learnt from these mistakes. There’s currently a vocabulary challenge running over at Hacking Chinese Challenges, and even if you learn about this when it’s too late to join, you can still sign-up for the next round!

The real challenge when learning Chinese characters

When you first start learning Chinese characters, the struggle is to remember how to write the components (even if you might not think of them as components yet).

Everything is new and the challenge is to remember what a component looks like, how the strokes fit together, stroke order. and so on. Learning new characters is difficult.

When you have learnt Chinese for a while, the situation changes. You now know most of the common components, and writing them becomes trivial. You sometimes forget which component it’s supposed to be, but you seldom forget how to write the component itself. Learning new characters is pretty easy, but a new challenge emerges: keeping similar characters apart.

I have written more about this in this article:

I place myself squarely in the second category. I almost never forget how to write a part of a character, it’s mostly a matter of not remembering what component it’s supposed to be or mixing it up with a similar component.

Thus, the mistakes that I will share with you below might be more useful for intermediate and advanced learners. It might not be useful because you struggle with the same characters as I do, but because the underlying principles are the same and the solutions are applicable to your problems, too.

I should also note that I’m mostly focusing on traditional characters, but that the general principles of course apply to simplified characters as well!

If you’re a beginner, you should probably read this article instead:

7 mistakes I made when writing Chinese characters and what I learnt from them

Below, I present seven mistakes I made recently when reviewing characters in Skritter. I explain what I wrote, what I was supposed to write and then try to analyse and categorise the mistake.

I then describe my solution to the problem and how I deal with this kind of problem. This is a way of tracing my errors, which I recommend you do, too. I’ve written about that in this article:

Taking decisive action is the only option when it comes to learning characters, because ignoring tricky vocabulary will just turn them into leeches that drain both time and energy.

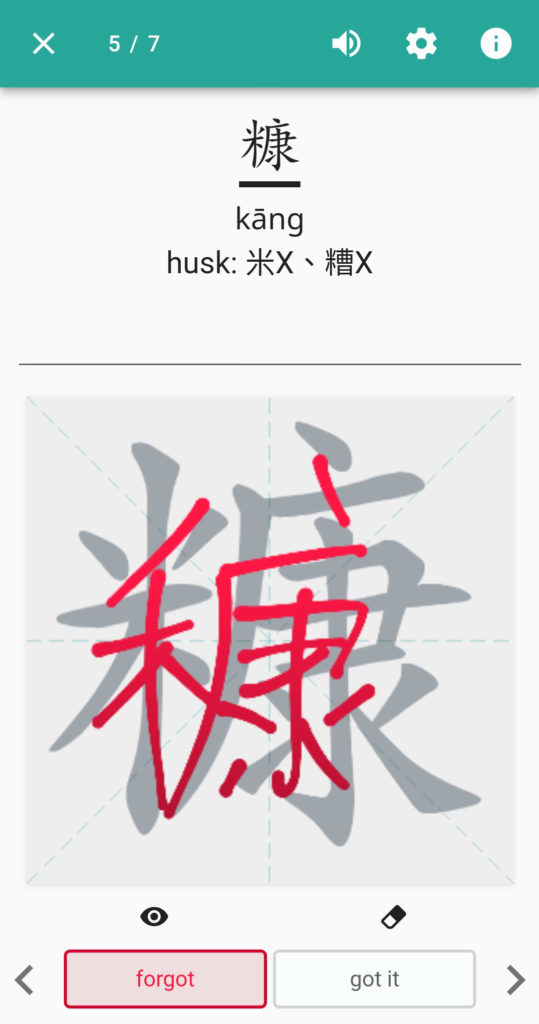

Mistake #1: Writing 禾 instead of 米

What I should have written: 糠, kāng, “chaff; husk”

What I should have written: 糠, kāng, “chaff; husk”- What I wrote instead: 穅 (this character is exceedingly rare and I have not studied it)

- Analysis: These characters are phono-semantic compounds where the right part indicates the sound and the left part indicates the meaning. I sometimes find it hard to remember if characters with meanings related to cereal or grain uses 禾, “grain”, or 米, “rice”. There are plenty of each, so guessing doesn’t work. Here I got it wrong.

- Note: If you struggle with the right part here and keep mixing it up with e.g. 唐 and 庸, you need to pay more attention to phonetic components, because characters containing 唐 are pronounced tang and those with 庸 are pronounced yong.

- Solution: I associate the right part with the 康熙 emperor, so I summon up the picture of a hale and hearty-looking emperor (flushed cheeks). I see him sitting by a table, carefully removing the husks from his rice; the secret to his healthy demeanor. I also add another word with this character in it to my deck so that I see it a bit more often for a while.

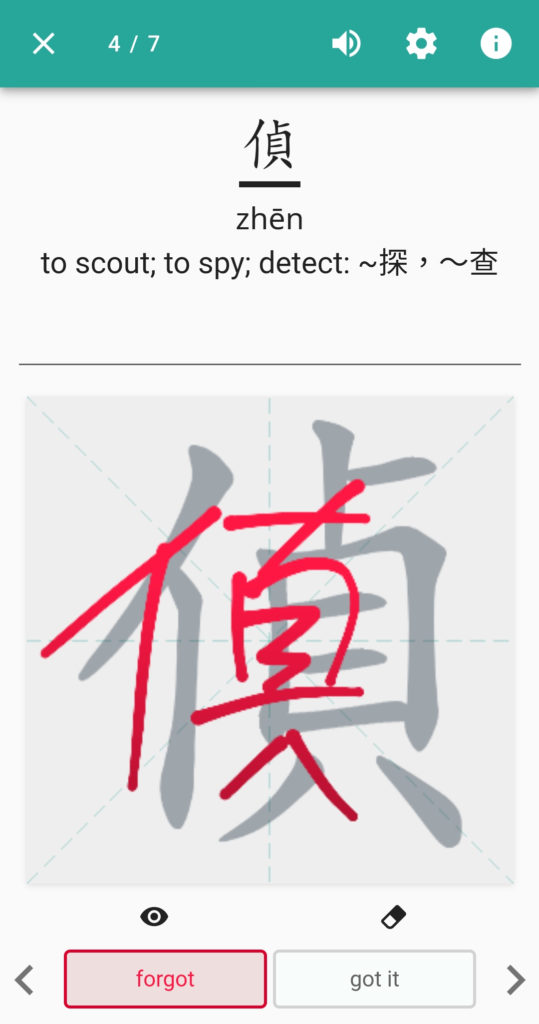

Mistake #2: Writing 真 instead of 貞

What I should have written: 偵, zhēn, “scout; seek out”

What I should have written: 偵, zhēn, “scout; seek out”- What I wrote instead: ⿰ 亻真 (this character does not exist)

- Analysis: This is a case of guessing too quickly and not thinking before writing. I know the pronunciation well, as this character is fairly common, but I forgot that it has a somewhat unusual phonetic component.

- Solution: Outlier Linguistics Dictionary of Chinese Characters says that 亻, “person”, is semantic and that 貞, zhēn, “loyal; chaste”, is both phonetic and semantic. I had never considered that it could be semantic here, to be honest. The original meaning is “divination”, which seems related to the meaning “seek out”. This is quite helpful, but I still add an extra word with this character to see it a bit more often.

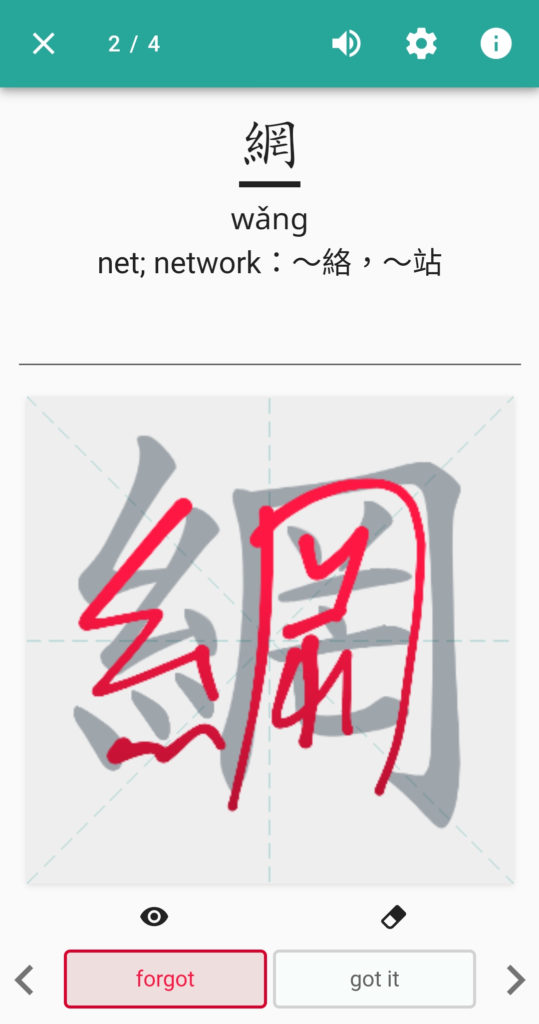

Mistake #3: Writing 岡 instead of 罔

What I should have written: 網, wǎng, “net; network”

What I should have written: 網, wǎng, “net; network”- What I wrote instead: 綱, gāng, “headrope of fishing net; guiding principle”

- Analysis: Both these have meaning components on the left and sound components on the right, and they both have the same ending, so no alarm bell rings because the composition is plausible. Both characters are fairly common.

- Solution: This mistakes is blindingly obvious with hindsight and I don’t know why I made it. The fact is that 罔 is pronounced wǎng and that all characters it appears in are also pronounced wang (it also has 亡 in it, which is also pronounced wáng), while 岡 is pronounced gāng, and all characters it appears in are also pronounced liket hat. Furthermore, Outlier Linguistics Dictionary of Chinese Characters notes that 罔 is also a meaning component (it means “net”), which is quite obvious in retrospect. Just noticing these things will make it highly unlikely that I mess any of these characters up again.

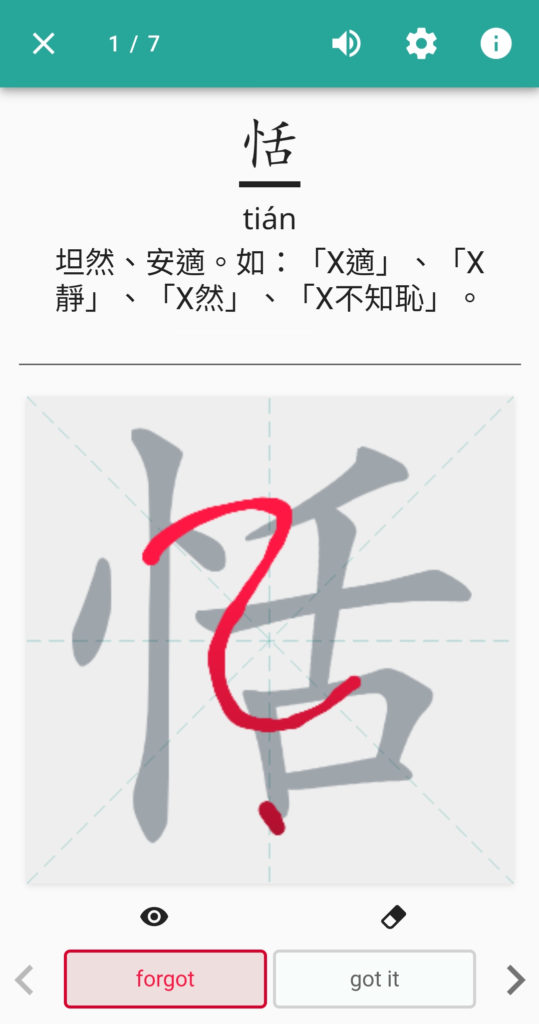

Mistake #4: Completely forgetting how to write 恬

What I should have written: 恬, tián, “quite; tranquil”

What I should have written: 恬, tián, “quite; tranquil”- What I wrote instead: Nothing

- Analysis: This happens to most people sometimes: You want to write something and you just draw a blank. I could not for the life of me remember how to write this character. If you had asked me the day before or the day after, maybe I would have remembered it, maybe not. I think part of the difficulty here is that the phonetic component is not obvious. It seems to be half of 甜, tián, but I would spontaneously not think of only the left part having this pronunciation.

- Solution: This kind of mistake can be hard to avoid entirely, but in this case, there seems to be a solution in that 甜 is i very easy character and is the abbreviated sound component in 恬. Now that I know that and have spent all this time writing about the character, I probably won’t forget it anytime soon!

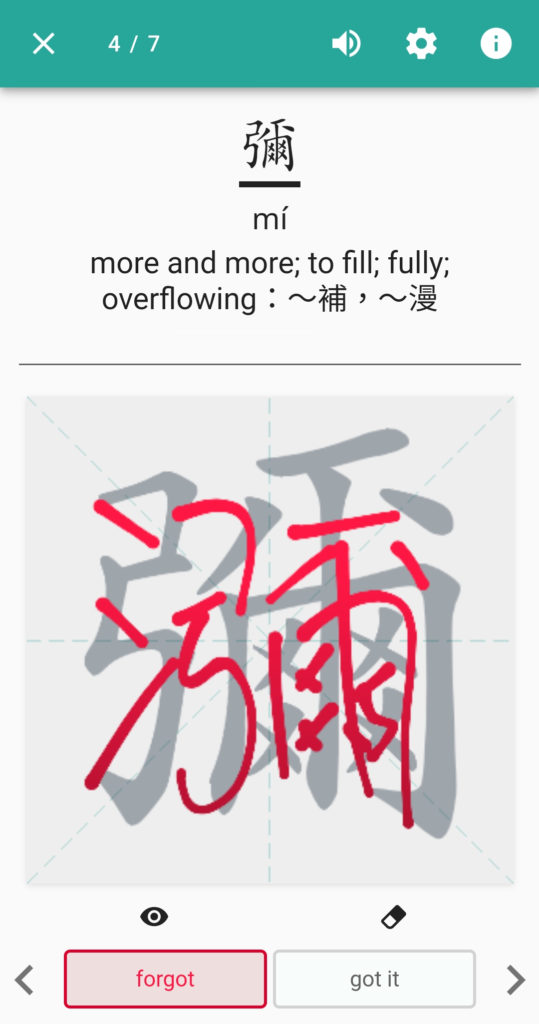

Mistake #5: Adding an extra 氵 to 彌

What I should have written: 彌, mí, “overflow; fill”

What I should have written: 彌, mí, “overflow; fill”- What I wrote instead: 瀰, mí, “overflow; fill”

- Analysis: I have learnt both these characters and obviously can’t keep track of which is which. After looking into this further, 瀰 is a rarely used variant that overlaps more or less completely with 彌 in modern Chinese. It has a simplified counterpart, but it sits snugly on rank 6714 in a frequency list, so it’s not very common. Taiwan’s MoE dictionary also refers to 彌, even though 瀰 has its own entry.

- Solution: I don’t know why I decided to learn 瀰. It’s exceedingly rare and keeps tripping me up, so I’ll just delete that character. Obviously, I can only delete it from Skritter, not delete it from my memory. Maybe I will add the three drops of water by mistake again some time, but having talked about it here and doing the research makes that less likely.

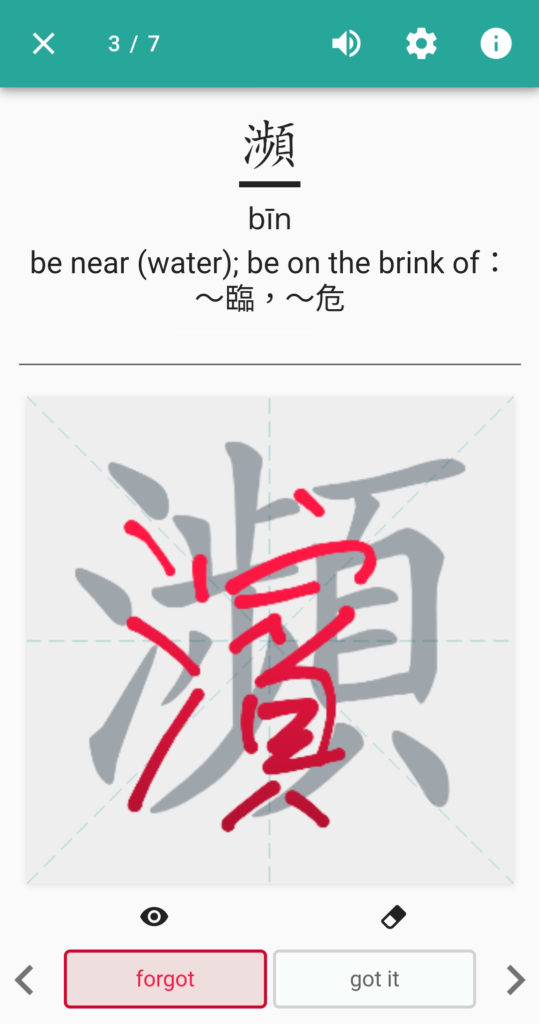

Mistake #6: Mixing up 瀕 and 濱

What I should have written: 瀕, bīn, “close to; border on”

What I should have written: 瀕, bīn, “close to; border on”- What I wrote instead: 濱, bīn, “close to; border on”

- Analysis: These characters have the same pronunciation and the same meaning, but slightly different usages. 濱 is a straight-up phono-semantic compound, but I’m somewhat confused by 瀕. My amateur intuition tells me that it’s probably phonetic 頻 pín and semantic 氵, but Outlier says it should be semantic 涉, “wade into water” (which is easy enough) plus 頁 “head”, which is a form component. Other sources I can find concur, so this is really interesting, because it’s so easy to think that 頻 is a sound component! Both ways of analysing the character helps, but the correct way makes it easier to keep this character separate from 濱.

- Solution: The above analysis has little to do with the actual problem, which is mixing up 瀕 and 濱. They mean roughly the same thing, but are used in different situations. 瀕 is used more as a verb (such as in 瀕臨) and 濱 is often used with a noun directly after it, as in 濱海. I know this, because I asked about it on Stack Chinese eight years ago (time really does fly). My problem here was that the prompt in Skritter didn’t include a proper clue, so I wrote the wrong character. I added propre context and will probably get it right from now on (in the screenshot it has already been fixed).

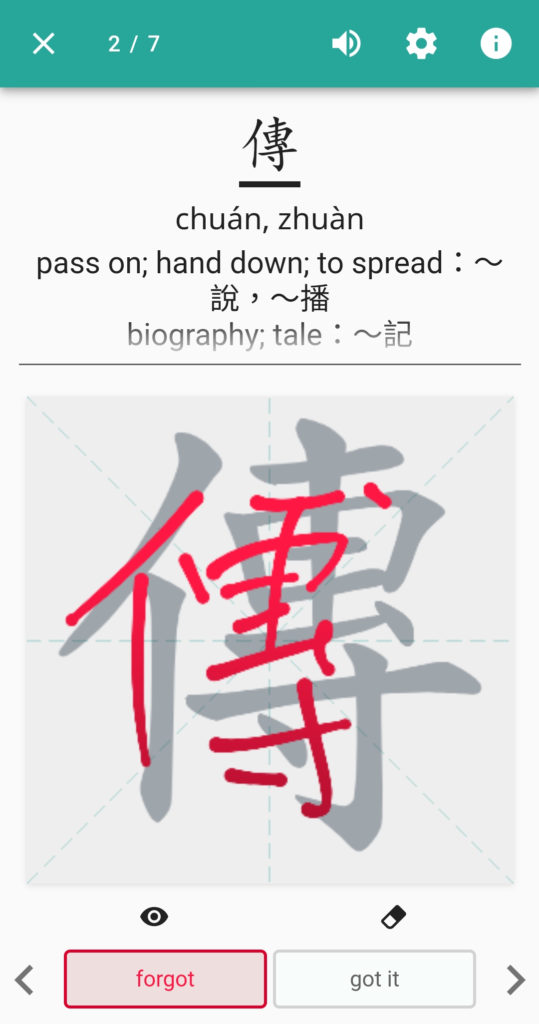

Mistake #7: Adding an extra dot to 傳

What I should have written: 傳, chuán, “pass on; transmit”

What I should have written: 傳, chuán, “pass on; transmit”- What I wrote instead: 傳 with an extra dot

- Analysis: Small, meaningless things are the hardest to remember, which is why we need to make them meaningful. I discussed in this article how paying attention to phonetic components can make even a single dot meaningful, so let’s see if we can figure something out here. After removing extra fluff (亻 and 寸), we have 叀 left, which according to Outlier is “a kind of tile used in weaving”. No dot. There are some similar components that do have dots, though, such as 甫, which is where I think I got the dot from. It’s used in male names and also has some uses in classical Chinese, but it also seems related to 父 (it’s even listed a sa phono-semantic compounds in some sources, with 父 being the phonetic component and 用 being the semantic component).

- Solution: This is a very good example of a problem that only appears in handwriting, as I’d never misread these characters or mistype them. I think that the reference to 父 here might help, using it as a memory hook to know when there’s supposed to be a dot. There is a possibility I’m adding the dot for some other reason, though, but this is a good start!

Naturally, I have forgotten more than seven characters, but most of them are of the “I have no idea what I’m supposed to write here” or “I should have created a better prompt for this”, so they aren’t very interesting to analyse.

Conclusion: Rote learning does not work

What is abundantly clear to me after having learnt Chinese for all these years is that rote learning, i.e. trying to remember how to write Chinese characters simply by repeating them a lot without really understanding what’s going on, really doesn’t work.

Of course, it works for native speakers, but they spend thousands of hours on handwriting over twelve years of compulsory education and countless nights of extra homework. I don’t want to do that and I doubt you want to do that either.

The only solution is to constantly deepen your knowledge of how characters work, find meaningful ways of practising and tracing errors when they occur. If you’re like me and want an efficient (a fancy word for lazy) approach to learning, I suggest you check out this article:

A minimum-effort approach to writing Chinese characters by hand

In this article, I shared seven mistakes I’ve made recently in my character reviews. What characters are you struggling with? What did you learn by looking them up and tracing the error to its source?

You probably don’t struggle with the same characters as I do, but as I hope you have benefited from reading this article, we can also benefit from reading about your learning, so please leave a comment and share your experience below!

5 comments

On your “Mistake #2” I have a book of “handwritten Chinese”-technically Xing-Style fonts, and the way you wrote 貞 actually looks exactly like the one in my book.. I only looked it up because I recently looked up the same character in regards to a note I got. To be honest though, reading my friends’ handwritten notes lately got me so completely confused..it seems everyone has their own style and they rarely look like anything in the book they sent me.

I’ve come to the conclusion that reading & understanding notes written by physicians and scientists deserves its own specialized degree…? (I also usually have them drop me a message with their note’s “translation“ in WeChat..I PREFER just a typewritten note to start with but… ??)

Very interesting article, Olle! I appreciated getting a more intimate peek into your own study routines.

拨 and 拔 tripped me up recently as they look similar, have a similar pronunciation, and both involve an action with the hand. Of course this probably isn’t an issue in traditional writing, as 拨 is 撥. I don’t really have a great solution at this time, other than 拨 has the 发 component and so one meaning of 拨 (to allocate, set aside, or distribute, as in 拨款) is a bit similar to some meanings of 发.

I agree with every single point in your article except maybe the conclusion part. I would argue that if you’re learning Chinese as a second language rote learning might work, especially in combination with understanding the etymology and stroke composition of a character. I guesss it worked for me (though, I’m not very proficient 🙁

I’d also like to make a point about traditional vs simplified. It seems like traditional characters are easier to memorise mnemonically, whereas simplified are stripped of many useful clues.

I have a question. I read on https://pandaspeakschinese.com/chinese-names-general-information that Mandarin and Cantonese speakers enjoy 100% intelligibility in writing. Does that also mean that people from mainland China can easily read traditional and vice versa?

I think maybe we use different definitions of “rote learning”! You say “rote learning might work, especially in combination with understanding the etymology and stroke composition of a character”, but I would argue that that isn’t rote learning any more. 🙂 Merriam Webster defines “rote” as “the use of memory usually with little intelligence: learn by rote”. So I agree with you, rote learning works if you add understanding to it. 🙂

The other questions are a bit trickier. Written colloquial Cantonese is definitely not mutually comprehensible with written Mandarin, although it’s sometimes possible to guess what some things mean. The reason people say that is because people who speak Cantonese write in Mandarin. This question on SE Chinese might help clarify things for you. When it comes to simplified and traditional Chinese, you can check this article, which gives a very in-depth answer to the question of which is easier. As to your last question, learning to read the other set is very easy. Learning to use it actively in handwriting is harder, but not anywhere near as hard as learning to write in the first place.

Useful post, It’s best to learn from other’s mistakes than to feel the urge to commit one by oneself & then think of learning. I think we’ve all made some of these mistakes to some degree or another.