Listening and reading in Chinese can be a challenge, especially when your level is not high enough. To understand more and thereby also learn more, use scaffolding!

Listening and reading in Chinese can be a challenge, especially when your level is not high enough. To understand more and thereby also learn more, use scaffolding!

The idea behind scaffolding is to erect porting structures to allow you to perform at a more advanced level, then gradually remove these structures until you learn to manage without them.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

A very simple example would be to read a text in Chinese with the aid of a dictionary. This allows you to access texts that would be too difficult without any supporting structures. As you keep reading texts at a similar level, you will need to use the dictionary less and less, until one day you can read and understand unaided.

8 great ways to scaffold your Chinese listening and reading

In this article, I want to discuss ways of scaffolding your Chinese listening and reading practice. Like most articles here on Hacking Chinese, this article takes a student’s perspective, but when it comes to scaffolding, teachers are uniquely well-placed to provide scaffolding if they know their students.

For example, when I teach Chinese, I can find different ways of supporting the students’ understanding by using language they know. When using my adventure text game 逃出去 in a classroom, I can scaffold their listening and reading by drawing maps or pictures, using simple props or paraphrasing.

This is harder to do for yourself as a student because comprehension is a prerequisite for creating such scaffolding; you can’t draw an image illustrating a scene if you don’t understand the language used to describe that scene!

Still, there are some ways you can scaffold your Chinese listening and reading practice as a student, without the aid of a teacher. This is what this article is about!

Easy Chinese unaided or difficult Chinese with scaffolding

Before we dive into different ways of scaffolding your Chinese listening and reading practice, I want to preface that discussion with a reminder that scaffolding is not always the best option.

Scaffolding is about adding support that allows you to deal with tasks that you could otherwise not perform. However, while this is useful, it doesn’t mean that scaffolding is always the best idea or that you should focus on material way above your level. This is especially true when the scaffolding takes time and energy to use, such as when using a dictionary to look up unknown words, or when using the scaffolding detracts from the practice itself, such as if you rely on Pinyin instead of reading the characters.

So, while a beginner could in theory read an authentic newspaper article in Chinese with the aid of a pop-up dictionary and a grammar reference resource, this is not a good idea, because you end up spending most of your time on the scaffolding, not processing the language in the article.

Instead, your first option should always be to choose listening and reading materials at an appropriate level. For most of your practice time, this means material you can deal with with minimal or no scaffolding. Only use scaffolding when you have to tackle something harder or when you’re truly motivated to do so.

To help you find suitable listening and reading resources, I have compiled two curated lists of the best recommendations on all levels:

The 10 best free Chinese listening resources for beginner, intermediate and advanced learners

The 10 best free Chinese listening resources for beginner, intermediate and advanced learners

The 10 best free Chinese reading resources for beginner, intermediate and advanced learners

The 10 best free Chinese reading resources for beginner, intermediate and advanced learners

As a beginner, you often don’t have much choice, as most listening and reading resources will be hard for you without scaffolding. For more advice about beginner listening and reading, check these two articles:

The best Chinese reading practice for beginners

Beginner Chinese listening practice: What to listen to and how

Beginner Chinese listening practice: What to listen to and how

4 ways of scaffolding your Chinese listening practice

There are many reasons why you might struggle to understand something said in Chinese, and depending on what the reason is, different scaffolding is needed. If you’re not used to meaning-focused listening, simply listening to the same passage more than once might do the trick, but if your main problem is that you don’t know many of the important words, then using a dictionary will be more beneficial.

Here are four things you can try if the Chinese you listen to is a bit too challenging:

Listen more than once – Too many students give up after listening just once. In real life, you are indeed often limited to listening only once, but nothing says you can’t listen more than once when you practice on your own. Listening a second, third, fifth or twentieth time can do wonders for your comprehension! This should always be the first thing you try when listening to an unfamiliar passage: if you don’t understand hardly anything after the second listen, listen to something else. If your understanding increases with each listen, repeat until you’ve understood everything or until you feel bored (if so, return t the passage later). Learn more here: Listen more than once: How the replay button can help you learn more Chinese

Listen more than once – Too many students give up after listening just once. In real life, you are indeed often limited to listening only once, but nothing says you can’t listen more than once when you practice on your own. Listening a second, third, fifth or twentieth time can do wonders for your comprehension! This should always be the first thing you try when listening to an unfamiliar passage: if you don’t understand hardly anything after the second listen, listen to something else. If your understanding increases with each listen, repeat until you’ve understood everything or until you feel bored (if so, return t the passage later). Learn more here: Listen more than once: How the replay button can help you learn more Chinese Lower the rate of speech – There are three basic ways of slowing down spoken language: reducing the playback speed, inserting pauses and asking the speaker to talk more slowly. The last one is typically beyond your control as an independent student without a teacher, but the other two are feasible. To reduce playback speed, use the built-in feature for this on platforms like YouTube (cogwheel, “change playback speed”), or use a free program like Audacity (the effect is called “change tempo). Inserting pauses is somewhat tedious to do manually, but you can use Audacity to do it automatically by using plugins like Extend Silences. These three ways of lowering the rate of speech have different effects on your learning experience, and I think decreasing the tempo by using software is both the easiest and most useful.

Lower the rate of speech – There are three basic ways of slowing down spoken language: reducing the playback speed, inserting pauses and asking the speaker to talk more slowly. The last one is typically beyond your control as an independent student without a teacher, but the other two are feasible. To reduce playback speed, use the built-in feature for this on platforms like YouTube (cogwheel, “change playback speed”), or use a free program like Audacity (the effect is called “change tempo). Inserting pauses is somewhat tedious to do manually, but you can use Audacity to do it automatically by using plugins like Extend Silences. These three ways of lowering the rate of speech have different effects on your learning experience, and I think decreasing the tempo by using software is both the easiest and most useful. Use written support – Listening is difficult partly because it’s instantaneous; if you don’t understand something it’s gone after a few seconds. You can’t dwell on a specific word until understanding dawns like you can with reading. If you think it’s an unknown word, you need to be able to identify where it begins and ends, as well as to type the characters or at least the correct Pinyin to look it up. For this reason, using written support can be a good idea. This could be subtitles for a movie, close captions on YouTube, the lyrics to a song or the transcript of a podcast or news broadcast. However, as I have pointed out in the article Listen before you read: Improve your listening ability, make sure you listen before you read, otherwise, you’re not practising listening ability any more.

Use written support – Listening is difficult partly because it’s instantaneous; if you don’t understand something it’s gone after a few seconds. You can’t dwell on a specific word until understanding dawns like you can with reading. If you think it’s an unknown word, you need to be able to identify where it begins and ends, as well as to type the characters or at least the correct Pinyin to look it up. For this reason, using written support can be a good idea. This could be subtitles for a movie, close captions on YouTube, the lyrics to a song or the transcript of a podcast or news broadcast. However, as I have pointed out in the article Listen before you read: Improve your listening ability, make sure you listen before you read, otherwise, you’re not practising listening ability any more. Visualise or illustrate the audio – This is a non-linguistic version of the above. Instead of relying on written support, you can make use of other types of visual input, such as pictures, video or similar. A movie is easier to understand than a radio play, and a news broadcast on TV is not as hard as one on the radio). The reason is that you can understand much by just watching, which will help you process the spoken language. This is also more realistic than audio-only listening because, in real life, conversations often happen in a clear context! As a student, you can access visual support in two ways: First, select listening material that has a visual component, such as movies, TV series, articles with images, and stories with illustrations. Second, you can use AI to generate images for you. This is not always reliable and your mileage may vary depending on content and the AI service you use.

Visualise or illustrate the audio – This is a non-linguistic version of the above. Instead of relying on written support, you can make use of other types of visual input, such as pictures, video or similar. A movie is easier to understand than a radio play, and a news broadcast on TV is not as hard as one on the radio). The reason is that you can understand much by just watching, which will help you process the spoken language. This is also more realistic than audio-only listening because, in real life, conversations often happen in a clear context! As a student, you can access visual support in two ways: First, select listening material that has a visual component, such as movies, TV series, articles with images, and stories with illustrations. Second, you can use AI to generate images for you. This is not always reliable and your mileage may vary depending on content and the AI service you use.

There are more ways to scaffold your listening practice, but these broadly cover the ones you can do on your own. If you have further suggestions for outside-the-classroom situations, please leave a comment!

As mentioned, to scaffold your listening practice properly, it’s necessary to go beyond simply noticing that you didn’t understand. For a deep dive into how listening comprehension works for learners of Chinese, please refer to the series Beyond tīng bu dǒng, part 1: A guide to Chinese listening comprehension.

Beyond tīng bu dǒng, part 1: A guide to Chinese listening comprehension

4 ways of scaffolding your Chinese reading practice

Scaffolding for reading Chinese is a bit more straightforward, and you might be using some of these methods already. Let’s go through them to make sure you know about the tools you have available!

Use pop-up dictionaries – This is by far the most important tool of all. As David Moser points out in his guest article The new paperless revolution in Chinese reading, it’s something that has revolutionised Chinese reading. The main point is that when you can look up an unknown character or word in a fraction of a second, you can deal with difficult texts on less than geological timelines; no more time wasted flipping through the pages of a paper dictionary! This type of scaffolding is so powerful that you might be tempted to use it too much, so keep in mind that you will learn what you practise, meaning that if you never try to understand texts without the aid of a dictionary, you won’t develop the skills needed to read unaided.

Use pop-up dictionaries – This is by far the most important tool of all. As David Moser points out in his guest article The new paperless revolution in Chinese reading, it’s something that has revolutionised Chinese reading. The main point is that when you can look up an unknown character or word in a fraction of a second, you can deal with difficult texts on less than geological timelines; no more time wasted flipping through the pages of a paper dictionary! This type of scaffolding is so powerful that you might be tempted to use it too much, so keep in mind that you will learn what you practise, meaning that if you never try to understand texts without the aid of a dictionary, you won’t develop the skills needed to read unaided. Annotate the text – There are multiple ways you can annotate a text to make it easier to understand. This includes adding pronunciation in Pinyin, Zhuyin or just tone marks (check Purple Culture), and generating custom word lists (check Mandarin Spot). Generating wordlists is especially useful if you tend to overuse pop-up dictionaries; simply generate a word list and manually refer to it when needed. This is much faster than a traditional look-up in a printed dictionary, but significantly more effortful than simply clicking or tapping an unknown word. For more about using lists to enhance your learning, check Vocabulary lists that help you learn Chinese and how to use them.

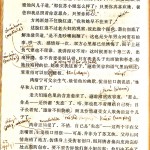

Annotate the text – There are multiple ways you can annotate a text to make it easier to understand. This includes adding pronunciation in Pinyin, Zhuyin or just tone marks (check Purple Culture), and generating custom word lists (check Mandarin Spot). Generating wordlists is especially useful if you tend to overuse pop-up dictionaries; simply generate a word list and manually refer to it when needed. This is much faster than a traditional look-up in a printed dictionary, but significantly more effortful than simply clicking or tapping an unknown word. For more about using lists to enhance your learning, check Vocabulary lists that help you learn Chinese and how to use them. Visualise the text – Most of what I said above about visualising spoken Chinese can also be done for text, and it’s easier too! Naturally, you should start by picking reading resources that already have some visualisation, from simple illustrations or pictures to graphic novels and comics. As was the case for listening comprehension, simply having some idea of the context the language appears in makes it easier to understand. With fully visual media, such as graphic novels and comics, the illustrations will support you a lot!

Visualise the text – Most of what I said above about visualising spoken Chinese can also be done for text, and it’s easier too! Naturally, you should start by picking reading resources that already have some visualisation, from simple illustrations or pictures to graphic novels and comics. As was the case for listening comprehension, simply having some idea of the context the language appears in makes it easier to understand. With fully visual media, such as graphic novels and comics, the illustrations will support you a lot!- Listen to the written text – For people who have more problems with reading than listening, being able to hear the written text can help a lot. There are many ways of doing this. To start with, you can use the same type of resources as you do for listening provided that they have transcripts but instead focus on the written text first. For example, read a written news article and then use the spoken version to fill in the blanks. Text-to-speech has also become very good and is now at a level where it works well for at least some listening practice.

Conclusion: Scaffolding can be very useful, but don’t overdo it!

It’s important to adjust your Chinese listening and reading practice to a level that is suitable for your current level, your current state of mind and the specific situation you’re in. This vastly increases the material available to you and by making you understand more, you will also learn more.

Here, scaffolding can play an important role, broadening the scope of Chinese you can access, offering more variety and a more interesting learning experience. Remember, understanding is key for learning, so if you don’t understand what you’re listening to or reading, scaffold it so you can understand!

Or just choose easier listening or reading material in the first. place. Don’t fall into the trap of focusing on difficult Chinese too much. This won’t expose you to enough language to help you build a mental model of how the language works, what words mean and so on. Reading ten relatively easy texts is almost always preferable over reading one relatively difficult text of the same length.

Finally, I would like to hear what you think. Are you using some kind of scaffolding I haven’t mentioned here? Do you have a clever approach that perhaps fits in one of the categories, but you want to share it with me and others because it’s so useful? Leave a comment below or check out what others have already written!

Editor’s note: This article, originally published in 2017, was rewritten from scratch and massively updated in January 2024.

7 comments

For reading Chinese text on Android devices, you can consider our Hanping Chinese Popup app. This app works on top of whichever app you happen to be using so you don’t need to take a screenshot and/or leave the app you are using.

You can find a video demo in the app store listing: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.embermitre.hanping.app.popup

Thanks!

Good point! I’ll wait a bit longer until there are more suggestions for things I have missed and then update the article.

FlipWord is a great app for learning effortlessly. It is quite simple and effortless yet also quite different from other apps. It is currently available as an add-on for Google Chrome. https://flipword.co/

Great article. For more advanced learners, try the app ”得到“ by 罗辑思维‘s presenter 罗胖. You can download tonnes of little free snippets of audio talking about various interesting topics betwen 3-5 mins each. The audio can also be slowed down to 0.7x speed instead of the more common 0.5x speed, which makes a world of difference (as in the narrator sounds chilled out, not drunk!).

If you do intend on slowing the audio though, I would advise you change the settings to only download the guest narrators audio as 罗胖’s 安徽 accent makes him hilariously inebriated.

Here’s the best part: You can download everything and play it over and over, and also read any article you’re listening to at the same time.

This might be something you’d like to use yourself Ollie, if you aren’t already. It’s been very useful to me as a source of truly engaging advanced content on the go.

That’s a great suggestion; I’ll be sure to check it out!

Actually, a “drunkard” is someone who is habitually drunk – and might be capable of speaking quickly. Someone who has over-imbibed is just at “drunk”. Yes, it’s nitpicking, but in the absence of an editor, you’ll have to put up with me. 😀

Thank you for the correction! I must have missed your comment when you posted it, but now, four years later, I’m referring to this article in a podcast and saw your comment. I always appreciate help with fixing mistakes!