One of the biggest challenges learning Chinese as an adult is to master the tones. While some students have an easier time, the large majority of students struggle with even with basic tones and tone combinations.

One of the biggest challenges learning Chinese as an adult is to master the tones. While some students have an easier time, the large majority of students struggle with even with basic tones and tone combinations.

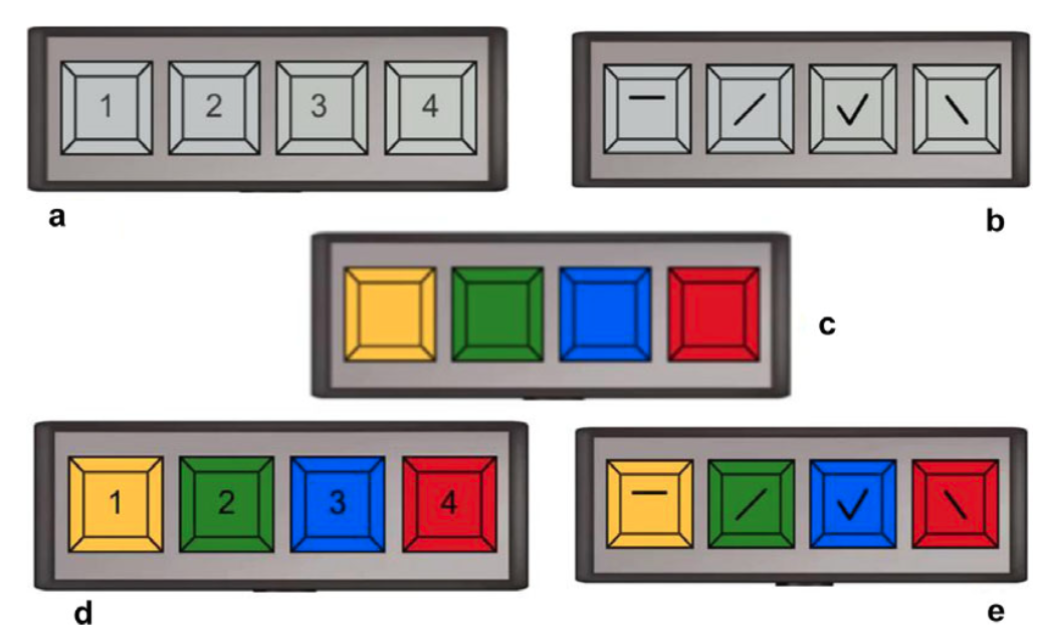

Many things have been tried to make tone learning easier, including various forms of visual representation, such as using tone marks or symbols (jiēmì zhōngwén) or tone numbers (jie1mi4 zhong1wen2).

Another such representation is colour, meaning that each tone associated with a certain colour, often in combination with some other representation, such as tone marks (jiēmì zhōngwén). It’s also possible to ignore the Pinyin altogether and simply colourise the Chinese characters directly: 揭密中文.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many other platforms!

In this article, I will discuss using colours to learn and remember tones. I will talk about why it can be helpful, what research tells us about it’s role as a learning tool, and some tools you can use if you want to spice up your learning with nifty colours.

This article doesn’t cover learning tones in general, so if you want to learn more about that, please check out The Hacking Chinese guide to Mandarin tones.

Does using colour to represent Mandarin tones make them easier to learn?

While this question may seem straightforward, it hides at least three different questions:

- Does adding colour make it easier to learn to hear/say tones?

- Does adding colour make it easier to remember tones?

- Does adding colour have some other practical benefit for learners?

I will discuss each of these separately, because as we shall see, which aspect you look at has a big impact on the answer of whether colours really do help or not.

Does adding colour make it easier to learn to hear/say tones?

Learning tones is a complex process and something I’ve spent a lot of time researching myself. I have summarised the passive (listening) part of tone learning in this article: How to learn to hear the tones in Mandarin.

One thing I’ve learnt after reading almost everything published about this specific topic is that what intuitively seems to make sense doesn’t always work.

For example, adding more information doesn’t always make it easier to learn (so adding both tone marks and colours might sound like it should be better than leaving one of them out, but this isn’t necessarily the case; see Van Merrienboer & Sweller, 2005). Another example is that minimal feedback (right or wrong) can be more useful than more verbose feedback (right or wrong, plus what ought to have done; see Maddox et al. 2008).

So, even if the gut reaction is “why not”, just adding colour support to the learning process might not be a good idea. Fortunately, there is some empirical research into this very question.

In 2017, Godfroid, Lin and Ryu conducted an experiment with zero beginners, comparing different visual representations, namely tone mark, tone number and colour. They found that all three had positive effects, but that colour did worse, especially in tests done some time after the initial learning took place.

This, however, doesn’t tell us much, because I don’t think anyone really proposes to use only tone colour, but rather to use colour in combination with some other support, such as tone marks (e.g. jiēmì zhōngwén). Fortunately, they tested this as well, but found no significant benefit compared to using only tone marks or tone numbers. To put it very briefly, adding fancy colours didn’t improve learning compared to traditional black-and-white, but actually performed slightly worse.

Naturally, this is only one study and it only pertains to the learning process for beginners. Maybe it would have been different in the long-term, maybe different students would have preformed differently, or maybe the colours chosen were not the right ones (more about this later). But then again, it’s perfectly reasonable to assume, for now, that adding colours in the learning process does not make it easier to learn tones.

Does adding colour make it easier to remember tones?

To the casual reader, this question may look similar to the previous one, but it is in fact very different. In order to pronounce tones correctly, it’s not enough to learn how to say them, you also need to remember what tone or combination of tones a word has. This is much more akin to recalling other aspects of vocabulary, such as other parts of pronunciation or even meaning.

The question of recall was not tested in the study cited above and it’s much more reasonable to assume that more indeed is better when it comes to recall. In general, using different paths to the same information is beneficial for recall, including using different senses (modalities).

One concrete way of using colours to remember tones is to use them as part of your mnemonics. I will not go into memory techniques in detail in this article, but one way of doing it would be to associate each colour with an element, and then include that element in your mnemonics. Like so:

- High tone, red, fire – Put the story/picture in a burning inferno

- Rising tone, yellow, gold – Coat everything in gold or make it shine

- Low tone, green, vegetation – Visualise the story/picture in a jungle

- Falling tone, blue, water – Let the story/picture take place under water

I have written more about this here:

There are other ways colours could be used, including more indirectly. Maybe after seeing the same colours being used for the same tones over and over, certain words will be easier to associate with the correct tones? Something similar has been investigated for learning gender in German, but I’m not sure if that’s entirely applicable to what we’re talking about here (see Dias de Oliveira Santos, 2015). Colour was found to not be beneficial in that study.

Does adding colour have some other practical benefit for learners?

Finally, let’s discuss some practical aspects of using colour to indicate tones. One benefit is that for most people, it’s easier to see colours than tone marks. I don’t have very good eyesight myself and colours could help me if the tone mark is simply too small. Another benefit is that colour can be easily applied to characters to indicate tones without even showing Pinyin (揭密中文). I’ve written more about this here:

Focusing on Chinese tones without being distracted by Pinyin

For some people, this might be more intrusive than adding tone marks, but for others, the mixed colours might be distracting. I prefer tone marks myself, but I can see why some people like colours.

What colour should represent what tone?

I’m sure many of you think using red for the first tone is deeply unintuitive. Maybe you prefer blue instead? The paper by Godfroid, Lin and Ryu (2017) cited above actually has an overview of research into mapping colour to pitch, basically stating that lower pitch and falling tones are generally associated with darker colours. They ended up with a colour scheme that looks like this (from page 829):

However, I believe that which colours make sense is probably individual and is mostly determined by what colours you started out with.

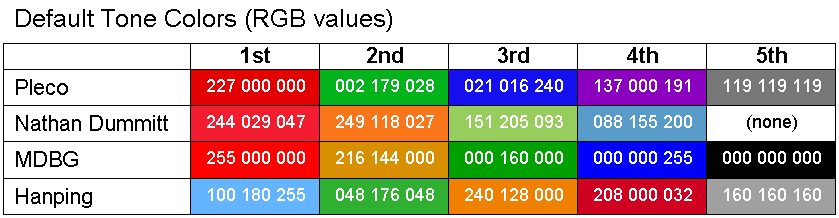

And this is important, because there are a lot of different systems being used. This table is from a blog post by Alfred Wolfe titled Tone Colors and What Pleco Did with Them:

If you want to learn more about the story behind these colours, I strongly suggest you read the whole article. For our purposes, though, it’s enough to conclude that it’s a mess. I mean, just look at the second and third tones! Half of these systems use orange/yellow for second tone, the other half uses green. Fine, but then for the third tone, the situation is almost reversed!

Advice for teachers, learning material authors and app developers

Any benefits with colours for tones is dependent on learning the mapping thoroughly, which is hard or impossible if different materials use different mappings. Therefore, if you teach beginners or create materials for them, then by all means use colours if you think it’s helpful, but make sure you pick one system and stick with it. Your students will not be familiar with any other way of doing it and will probably accept your mapping.

If you target anyone else, though, either skip the colour entirely or make it something the user can set as a preference. Being forced to use what amounts to the wrong colour-tone mapping is certainly bad and outweighs any marginal benefits colours might have.

Tools for colouring your Pinyin/characters

As promised, here are some tools you can check out if you like colours:

- This tone colouring tool from Purple Culture allows you to choose between six different colour mappings and is the one I recommend in the article about showing tones without Pinyin.

- Chinese Support Redux v0.13.0 for Anki allows you to automatically colour both Pinyin and characters for all your flashcards. This is not a reason to start using Anki if you aren’t already, but it is a neat plugin that may people simply don’t know about.

- Pleco can show tone colours, both for characters and Pinyin. As usual, Pleco is the best when it comes to configurability and you can actually choose exactly what colours to use for each tone. Very cool!

- Hanping also offers configurable colours (with the default shown in the list above). I think maybe in dictionaries is one of the few places where I truly appreciate colours, as it makes it considerably easier to quickly see the tone.

Do you know of any other tools that implement colours well or that can be used if you want to add colour to your learning? Be sure to let me know in the comments!

Conclusion

In summary, colours probably don’t make the initial learning process much easier. They can have some benefits for remembering tones if you use them correctly, though, and maybe colours have some other practical benefits, such as being useful for showing tones without Pinyin or simply being easier to see than tone marks.

However, the downside of all this is that colours have to be consistent to be useful, so it’s only really useful for beginners or when the student can choose which colours to use. Since there are so many different systems around, colour is likely to confuse more than it helps!

References

Dias de Oliveira Santos, V. (2015). Can colors, voices, and images help learners acquire the grammatical gender of German nouns?. Language Teaching Research, 19(4), 473-498.

Godfroid, A., Lin, C. H., & Ryu, C. (2017). Hearing and seeing tone through color: An efficacy study of web‐based, multimodal Chinese tone perception training. Language Learning, 67(4), 819-857. Accessible online here.

Maddox, W. T., Love, B. C., Glass, B. D., & Filoteo, J. V. (2008). When more is less: Feedback effects in perceptual category learning. Cognition, 108(2), 578–589. Accessible online here.

Van Merrienboer, J. J., & Sweller, J. (2005). Cognitive load theory and complex learning: Recent developments and future directions. Educational psychology review, 17(2), 147-177. Accessible online here.

Wolfe, A. (2014). Tone Colors and What Pleco Did with Them. Laowai Chinese 老外中文

Tips and Strategies for Learning to Speak Mandarin Chinese. Accessible online here.

11 comments

From my point of view, “not knowing the tone” usually entails “not knowing the pinyin at all”, so a reminder of the tone without the remaining pinyin is also useless.

When I write in LaTeX, I write pinyin with tones above unknown characters (and I strive to minimize these annotations), much like 语文 textbooks. I use colors, but not for tones: I highlight in separate colors (a) people’s names, (b) chengyu and other idioms, and (c) new words.

When I read, I edit in colors as I go. In addition to (a)–(c) above, I use colors for (d) measure words, and (e) words that I’m not (yet) interested in learning. (If I’m reading from a physical book, I’ll do this using pens and highlighters.)

Great article! I’d just like to point out that Hanping also allows you to configure tone colors exactly.

I have added Hanping! Sorry for always forgetting to include it, so thanks for reminding me!

Colour coding tones, was used by Michel Thomas decades ago…. to learn Mandarin. It works well, he coupled it with hand gestures too.

This wasn’t meant to be an historical overview, but what is your “it works well” based on? Do you mean that it works well for you, or that maybe he has some reason to think it works? I doubt there was any research into this that long ago, but I could of course be wrong. As the paper I cited indicates, though, students thinking that colours work doesn’t make them work! The group that used colours thought well of them in the post-experiment survey, yet they performed worse than the group that didn’t use colours. I’m not saying colours never work for anyone, but that the evidence so far seems to point that they don’t help on average.

…and the MT tone colours are different again to those listed above! (1st: green; 2nd: blue; 3rd: red; 4th black; none for 5th…)

I originally started with Trainchinese, and it might be good to mention this platform uses Dummit scheme exclusively. If anyone plan to use the Trainchinese resources, they should be aware of that when combining with Pleco and Hanping and configure them accordingly.

Hello Olle, Thanks for the article, especially the 2017, Godfroid, Lin and Ryu research paper. It completely supports my hypothesis that tone contour is the best method for increasing tone precision.

From my experience of a tone-deaf person trying to learn the tones, colors proved to be very useful when drilling the correct tone pitch in texts. Its a one less middle-step for my brain go through, hence faster and more fluent my production.

Personally I think it is not too good to use colors for remembering Chinese characters tones. Now let me tell you why I think so. Chinese is a language generated from 412 syllables adding 4(5) tones makes it around 1600. The problem I encounter when trying to recollect a specific character tones is that there are too many homophones, extreme amount compared to my native language. The other issue I see is that Chinese written discourse and Chinese spoken discourse are very dissimilar as to structures and characters used.

Chinese learners need the tones mostly for production, speaking. Reading, even when subvocalized, needs pinyin first, tones are secondary. For understanding and reading (subvocalization included) texts tones are marginal.

Does using colors to represent tones help learning the tones? I would argue it does not. In the sense that recollection of specific tone-character combination is not increased. However it helps me to find and practice tone pitch, focus more on tones and diction than the message.

I started with TrainChinese app. And they use the red, yellow, green , blue system. This is the system I have gotten used to and makes sense when you think of rainbow color order. AS long as you look at the vocab for arpund 30 days straight you will naturally remember the colors. Now for example, 老师 is always green, red and 现在 is always blue, blue in my head. I think it is a very useful technique.

I think it’s useful mostly because of the extra pegging it allows for. Remembering something abstract like a number or tone contour is rather hard, but if you have something concrete, like a colour, this makes it easier to create mnemonics, which can be great for remember the pronunciation of characters you don’t read aloud very often. I think colours are still too abstract, but the step to something like elements (blue = water, red = fire, etc.) is pretty small. I wrote more about this here if you’re interested!

But the thing is ..that… you don’t have to put any effort into remembering the tone colours. It will come naturally if you put a chart of vocab on your fridge etc.. and look at it once or twice for 25~30 days. After that it goes into long-term memory. And I know that many Hanxi have homophones using diiferent tones so this system is best mainly for words.