Learning characters is the most obvious challenge for students of Chinese. It’s obvious because no other world language requires you to learn thousands of unique symbols to be able to read and write; it’s a challenge because of the sheer number of characters and because there’s nothing similar in any other language, except Japanese.

Learning characters is the most obvious challenge for students of Chinese. It’s obvious because no other world language requires you to learn thousands of unique symbols to be able to read and write; it’s a challenge because of the sheer number of characters and because there’s nothing similar in any other language, except Japanese.

Understanding is key when learning something. Research clearly shows that learning meaningful things is much easier than learning meaningless things.

This becomes abundantly clear when learning Chinese characters. While it’s possible to learn to read and write by mindless repetition without understanding, this task is so daunting that it borders on being impossible for adult learners.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many other platforms!

In this article, we will look at five levels of understanding Chinese characters and how they relate to memorising characters. The levels range from surface structures to accurate understanding of how characters work. While more understanding is generally beneficial, I will argue that there’s a limit to how deep into the rabbit hole you should go.

Let’s see how much understanding you should aim for to get the most out of your learning!

5 levels of understanding Chinese characters: Superficial forms to deep structure

I have ranked the five levels and how they can be used for learning Chinese characters according to depth, with the most superficial form of understanding first and the deepest last:

- Inventing pictures that disregard composition and structure of characters

- Creating stories and associations that obscure functional components

- Using superficial pictures while being aware of functional components

- Using superficial pictures and encoding functional components

- Etymologically correct mnemonics with no shortcuts

Let’s have a look at each in turn to figure out how far down the list you should go.

Level 1: Inventing pictures that disregard composition and structure of characters

The most superficial form of understanding can’t really be called understanding at all, because instead of caring about how a character is composed, it only looks at the written form and finds something that at least the author or artist thinks resembles the character.

The most superficial form of understanding can’t really be called understanding at all, because instead of caring about how a character is composed, it only looks at the written form and finds something that at least the author or artist thinks resembles the character.

Such pictures have little use except as decoration or to attract the attention of children.

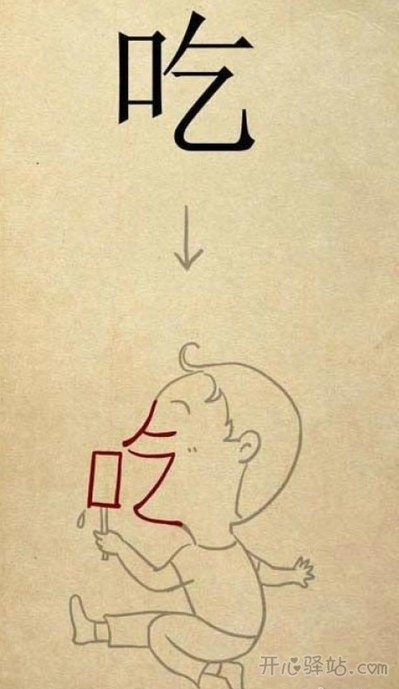

The picture on the right is a good example. Someone looked at the character 吃 (to eat) and thought that drawing a boy eating ice cream would make the character easier to remember.

And they may be right, but only if this is the only Chinese character you want to learn. 口 (“mouth; opening”) is a very common character component, so what are you going to do with other characters that share this component, such as 吗, 吧, 呢, 喝 叫 and so on? Are you going to draw 口 as ice cream in these cases, too?

If yes, then so be it, it’s just a bit unnecessary, but if no, you’re effectively making the task of learning to read and write Chinese many times harder. Learning thousands of unique pictures is much, much harder than learning combinations of a few hundred components.

To do this, however, you need to be consistent. The easiest way to be consistent is to use the real meaning whenever possible. Associating ice cream with 口 does not help you understand other characters, but learning that 口 means “mouth” or “opening” helps quite a bit.

I have written more about the problem of using pictures like this when learning characters:

If you want to learn Chinese for real and not just learn a few dozen characters for fun, I suggest that you stay as far away as you can from this type of learning material.

Level 2: Creating stories and associations that obscure functional components

The next step towards deeper understanding is to actually use the correct components, but to do so without being aware of their true relationship. This is very common in explanations of Chinese characters directed at people who don’t learn Chinese, and is often used to draw on ancient Chinese “wisdom”.

I’ve seen many examples of this, such as claiming that the ancient Chinese thought music had healing powers by pointing to the fact that 藥, “medicine”, contains the character 樂, “music” (this only works with traditional characters, because different components are used in simplified Chinese).

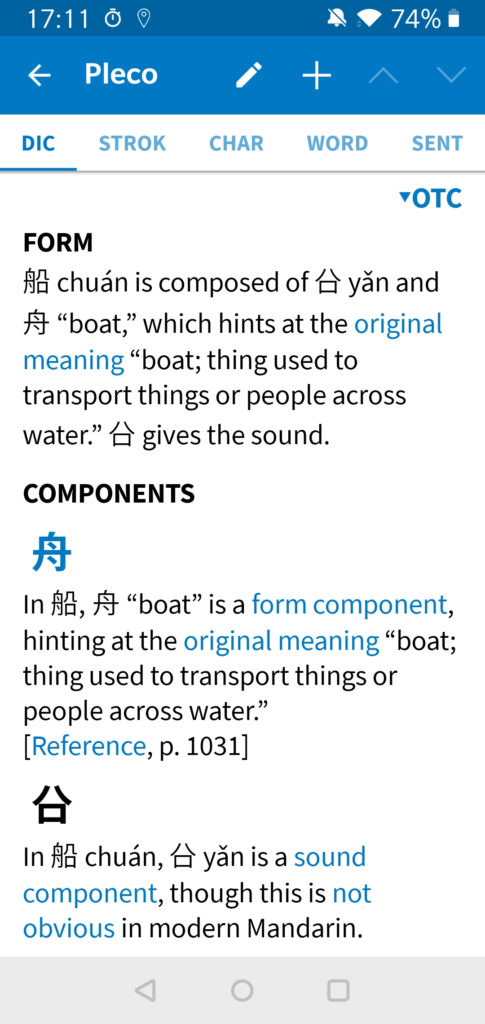

Another example is that the character 船, “boat”, alludes to Noah and his ark by saying that it contains 舟 “boat” and 八 “eight” 口 “mouth” (representing people), referring to Noah and his family. Both these are examples I’ve seen, by the way; I’m not making this up!

The problem is of course that to believe these stories, you need to have missed one of the most fundamental things about how Chinese characters work, namely that most characters contain components that are there for no other reason than to indicate pronunciation.

The real story is that 樂, “music”, is included in 藥, “medicine”, because originally, these characters were pronounced similarly or the same; only the grass component refers to the meaning of the character. In 船, 舟 means “boat”, but the right component is only there for pronunciation reasons (although that’s not obvious in modern Mandarin).

Learn more about phonetic components in these articles:

- Phonetic components, part 1: The key to 80% of all Chinese characters

- Phonetic components, part 2: Hacking Chinese characters

Another example of this is components whose superficial form is actually different from its actual function. For example, in 美 “beautiful”, the top part looks like 羊 “sheep”, but it is some kind of headgear (the bottom part is the person wearing the headgear). Thinking that 美 consists of “sheep” and “big” gives you the superficial form, but hides the true etymology.

I would advise students and teachers to not stop on this level because without knowledge about phonetic components, you haven’t even begun to understand how Chinese characters work.

Level 3: Using superficial pictures while being aware of functional components

Next on our quest for true understanding and a better way of memorising characters is to do the same as above, but with the insight that a vast majority of characters are combinations of meaning and sound components, just like the two characters for “medicine” and “boat” in the previous section.

However, it’s a fact that concrete images are easier to remember than abstract notions. Thus, one way of approaching the task of learning characters is to deliberately make use of the method described in the previous section while being aware of how functional components work.

It’s far less problematic to invent the story about Noah and his ark to remember how to write 船 than it is to try to use that story to prove that the ancient Chinese were Christians. The first is a clever mnemonic device to remember the components, the second is just stupid.

When it comes to cases like 美 “beautiful” mentioned above, I think it’s enough to be aware that this is happening. Since the modern form is written exactly like 羊 plus 大, building mnemonics based on this is fine for practical reasons, although you should be aware of the fact that this is not actually how this character came to be.

Learn more about functional components here:

Why you should think of characters in terms of functional components

This is the first level where I think it’s okay for serious learners to stop. Knowing about functional components will help you remember the characters, how to write them and sometimes even how to pronounce them. Combine that with a vivid and easy-to-remember mnemonic and you’re good to go.

Almost all my own character memorisation takes place on this level.

Level 4: Using superficial pictures and encoding functional components

Outlier Linguistics dictionary in Pleco.

If you really care about functional components and maybe have an interest in characters beyond their use for communication, you can deliberately encode information about functional components in the mnemonics you create. I seldom find it necessary to do so myself, but my friend Ash Henson from Outlier Linguistics suggested that it could be helpful if etymological correctness is highly valued.

There are many ways of doing this, but the most straightforward is to incorporate a specific element into each story or picture you make that lets you know what function a certain component has. Meaning components don’t need any special treatment if you use a picture matching the actual meaning of the component of course, but to indicate sound components, you could picture them as being made out of glass or something similar. This is a bit like using elements to represent tones.

For example, if you’re using the picture of Noah and his family to remember how to write 船, then you visualise 舟 as a boat, nothing strange there as it actually is there to indicate the meaning “boat”, but then you picture the eight people (represented by eight mouths), but in your mental picture, they are transparent glass figurines rather than real people. You can do this consistently, which will allow you to remember that the right part of the character is not actually related to meaning.

You could do something similar with the empty component “sheep” in 美, “beautiful”.

Personally, I find this to be overkill in most cases, but I can also see that it could be useful sometimes.

Level 5: Etymologically correct mnemonics with no shortcuts

Finally, we reach the last level, where only true etymology is allowed. This means that you are only allowed to use etymologically correct mnemonics and that no shortcuts are allowed. No music-induced happiness or glass figurines here!

The problem with this approach is that our brains have a much easier time remembering concrete images. Meaning is easier to visualise than sound, for obvious reasons, so creating mnemonics becomes very hard.

I don’t advise anyone to be this strict when memorising characters, but maybe it is the natural result of learning to speak before you learn to write, at least in some cases. It can also be used by very advanced students who already know thousands of characters.

For example, if a native speaker or advanced learner encounters the character 鰈, which is not very common, it’s fairly easy to just think of it as “that fish which is pronounced dié“. While there could be more than one phonetic component that gives the sound dié, it’s not really necessary to form a mental image here, just seeing it once does the trick because it’s so regular and all the components are already well-known.

This is not really a strategy, but more something that occasionally just happens.

What level of understanding works best for you?

I place myself smack in the middle of my spectrum from superficial form to deep structure. I don’t mind using concrete images for phonetic components or using an empty component, even though I know it’s actually not what it looks like, as long as it helps me remember the character. I also enjoy looking into actual etymology to better understand the characters, but that is, at least for me, a separate process in most cases.

If you’re at all interested in the etymology of characters, I strongly suggest you check out Outlier Linguistics dictionary, which is an add-on to Pleco. This will make looking these things up a breeze.

What do you think? How much do you need to know about a character to really learn it? How much do you want to encode in your mnemonics? Leave a comment below!

16 comments

If the component requires a convoluted explanation (verbal or graphic), my memory won’t keep it. Since visualisation is also a challenge for me, I tend to be extremist (!) and need an etymologically rational explanation.

But there’s no contradiction between visual and etymological? I mean, many of the actual etymologically correct explanations are visual as well. I’m curious what you mean here, though, how do you create mnemonics if they aren’t visual? Or do you mean that you still associate concepts in a meaningful way, but verbally rather than actually visualising them taking place?

Thanks for this blog post. I took the Outlier Linguistics Character course last year, and I’m glad that I did. I am now more careful about accepting what I read in this area. Whatever memory tricks I manage to come up with, I want to stay aware of what the reality is.

Yes, I think it’s important to realise that you can separate the two. I think it’s perfectly acceptable to use outrageous mnemonics (those do after all often work better than reasonable ones), as long as you don’t think that that’s how it actually works!

Olle, I think I have read this five times. It gets better every time. I am at almost 500 characters, and almost every day I have to go back and relearn a character that is a component in another character, because of the ‘ice cream cone’ problem. I got the outlier dictionary for Pleco, and it helps enormously. I am trying to stay with levels four and five, along with outrageous visualizations and tone markers.

Thanks for the great work, as always!

A (very pedantic) correction: the modern form of 美 is not “written exactly like 羊 plus 大”. The stroke order and visual appearance of the upper part of 美 is not the same.

Yes, what I meant was “written exactly like 羊 is written when it’s the top component in other characters and it actually is 羊”!

It’s far less problematic to invent the story about Noah and his ark to remember how to write 船 than it is to try to use that story to prove that the ancient Chinese were actually Christians. The first is a clever mnemonic device to remember the components, the (second is just stupid.)

1. The use of stupid, helps to…,in what way

2. …It’s far less problematic to invent the story about Noah and his ark to remember to write 船 than it is to try to use that story to prove that the ancient Chinese were actually Christians. (Ancient Chinese were actually Christians), The use and making of this character was in what year, does it pre-date Christianity?

Hey Olle. I tried to make this brief given the question at hand. @Fearchar’s comment seemed to relate to my struggle regarding best approaches to learning characters.

My struggle is likely partly b/c I don’t fully understand how best to create a mnemonic (I’ve read your great articles).

My Current Strategy: if I fail to remember a word in Anki, I check SmartHanzi’s component breakdowns (drawn from an Etymological Dictionary that breaks characters into one phono-semantic and one semantic component). I guess this is ‘Level 5 depth’. DongChinese is my backup (it’s breakdowns differ; matching your teaching: characters have one semantic and one phonetic component).

My (untested) impression is that creating a “convoluted” story with many details (that don’t *logically* follow each other), might be difficult for me; I’m certainly overwhelmed by the prospect of having hundreds(+) of these stories, and the prospect of initially setting them up poorly vis-a-vis each other.

Whereas, if this dictionary’s authors are correct: that 94% of characters have one phono-semantic and one semantic component, then I can use logic (something we intuitively understand) to deduce character meanings, without creating anything additional (story or otherwise).

Yet, I assume a story often is more memorable, and that the meaning of characters is not (indeed often isn’t) straight-forwardly deduced by a learner who knows component meanings, (this is evident in the dictionary’s entries).

So perhaps the upfront work is more intimidating to me (inventing vivid stories, and doing so correctly vis-a-vis each other), but long-term retention is better. Whereas, I guess what I (and maybe Fearchar) are currently doing is relying on our existing understanding of logic/rationality to piece together the semantic and phono-semantic (actual/etymological) meanings of components.

E.g.,

1. ‘上’ often means ‘on/above’, and

2. ‘坡’ is made from ‘土’ ‘earth’ (Semantic) + ‘皮’ ‘align’ (Phonosem.);

together depicting: “aligned hillsides, slopes or embankments”.

So, granted I memorize the components (which is possible I think right(?); i.e., there aren’t too many),

my mind doesn’t need an additional unrelated story to link these two components/to realize the meaning of: ‘上坡’ (uphill; upslope; to move upwards, etc.). i.e., logic does that linking for me.

However, this linkage/realization is probably very difficult, because it’s not always crystal clear how the two components connect to create the word meaning (a comparatively small number of components cannot cover the hundreds of thousands of words/meanings), and (I think?) each component can mean multiple things.

And to your question, I guess the only way a visual story differs from this process is that there is less that is being created/invented (b/c 1. component meanings are memorized/known, 2. logic is intuitive to humans).

As you can see, I’m still unsure what strategy is better, but probably it’s your story/mnemonic method.

Appreciate any insight and advice you have, this has been bothering me a while.

Hi! You bring up some good questions here. In general, understanding is the key to remembering anything, so the first thing you should always do is to at least try to understand what you’re trying to memorise. For characters, this means looking at a serious explanation of it (not just a graphical breakdown). For words, it means understanding how word formation works, which will solve almost all casse for you. If you haven’t already, I suggest that you check out my series about the building blocks of Chinese, especially the part 5 and part 6, which are both about words. In most cases, no mnemonic is needed. Most people don’t need a fancy story to remember that “fire” + “vehicle” = “train”. At least for me, making sense of the construction is enough.

This is true for single characters as well, but it requires a thorough understand of how they work. The issue with characters, though, and this is the topic of this article, is that oftentimes, the true etymological explanation of the character is not helpful. I don’t think what you describe is on level 5, that would imply that you cut no corners and never invented anything. I like using the example of 看 to explain this. Most people, including native speakers and teachers, think that this is a hand shading an eye. It’s not. The top part is actually a corrupted phonetic component that is not used anywhere else as far as I know. Now, it would, in my opinion, be a mistake to ignore the hand-shading-an-eye visualisation, because that’s so easy to remember and makes so much sense, even if it’s wrong. This is the level 3 I advocate in this article: You split the character the correct way, but you are okay with making stuff up if necessary, and when you do so, you do so consistently. Level 3 also implies that you don’t make a point of remembering that the top of 看 is actually not a hand and not even a meaning component, because the goal is to remember how to write the character, not learn the origins of all characters.

I don’t think this fully answers your question, and if not, feel free to ask a follow-up question based on what I wrote! I’ll consider addressing this in an upcoming podcast episode, but it’ll need to be in a somewhat simplified form.

@Olle. Amazing. Thank you so much. That clears some things up.

Apologies, seems I’m unable to comment within comment threads (maybe it’s Safari).

1. “For characters, this means looking at a serious explanation of it (not just a graphical breakdown)”.

By ‘graphical breakdown’ you mean Level 1 depth, or otherwise just trying to remember the components and their orientation within a character without understanding semantic or phonetic meanings, correct?

2. You mention: “most characters contain components that are there for no other reason than to indicate pronunciation”. Is the SmartHanzi (sourced from EDHCC) etymological breakdown (that both character components have semantics, with one also hinting at phonetic) an accurate depiction (or otherwise inaccurate but helpful)? I see that Smart Hanzi lists the top of 看 as a hand. So, it seems a SmartHanzi-derived mnemonic would fall under Level 2 depth of understanding (except that it leaves room for phonetics)?

I’m struggling to word exactly how, but it seems this question has implications for which mnemonics/what strategy to use for learning characters.

3. “You split the character the correct way, but you are okay with making stuff up if necessary, and when you do so, you do so consistently.”

If I understand then, to be consistent, hypothetically if 看’s corrupted phonetic component did show up elsewhere, I should then treat it like a hand(?). Or because it doesn’t show up elsewhere, this question is irrelevant and I don’t need to worry about consistency in this rare case.

Maybe this is where I’m confused, and where the distinction between SmartHanzi’s etymological character component breakdown and the conventional (1 semantic, 1 phonetic) breakdown might clear things up(?).

Indeed, if we used a different character whose ostensibly phonetic component is used in other characters, SmartHanzi’s phono-*semantic* definition of that phonetic component would theoretically be worth remembering(?). But, perhaps this then just becomes a similar strategy to what you advocate – applying a meaning (be it visual or solely ‘logical’) to both char. components (e.g., eye + hand 看), even if one mnemonic is factually incorrect (the hand).

Albeit, thereafter it seems we return to the question of which mnemonic is most effective. This brings up 2 quick last questions. In the above case, we are applying made-up meanings to phonetic components when that is more helpful for remembering the character than trying to link the phonetic component to the character’s exact pronunciation ([1.] which would almost always be the case?). And, 2., is this Level 3 depth?).

1. “For characters, this means looking at a serious explanation of it (not just a graphical breakdown)”.

By ‘graphical breakdown’ you mean Level 1 depth, or otherwise just trying to remember the components and their orientation within a character without understanding semantic or phonetic meanings, correct?

Yes, I refer to tools that analyse characters only based on what they look like.

2. You mention: “most characters contain components that are there for no other reason than to indicate pronunciation”. Is the SmartHanzi (sourced from EDHCC) etymological breakdown (that both character components have semantics, with one also hinting at phonetic) an accurate depiction (or otherwise inaccurate but helpful)? I see that Smart Hanzi lists the top of 看 as a hand. So, it seems a SmartHanzi-derived mnemonic would fall under Level 2 depth of understanding (except that it leaves room for phonetics)?

I’m struggling to word exactly how, but it seems this question has implications for which mnemonics/what strategy to use for learning characters.

It’s hard for me to verify any single resource, as I’m not an expert in palaeography, but I always recommend using the Outlier Character Dictionary if you want more correct information.

3. “You split the character the correct way, but you are okay with making stuff up if necessary, and when you do so, you do so consistently.”

If I understand then, to be consistent, hypothetically if 看’s corrupted phonetic component did show up elsewhere, I should then treat it like a hand(?). Or because it doesn’t show up elsewhere, this question is irrelevant and I don’t need to worry about consistency in this rare case.

Yes

Maybe this is where I’m confused, and where the distinction between SmartHanzi’s etymological character component breakdown and the conventional (1 semantic, 1 phonetic) breakdown might clear things up(?).

Indeed, if we used a different character whose ostensibly phonetic component is used in other characters, SmartHanzi’s phono-*semantic* definition of that phonetic component would theoretically be worth remembering(?). But, perhaps this then just becomes a similar strategy to what you advocate – applying a meaning (be it visual or solely ‘logical’) to both char. components (e.g., eye + hand 看), even if one mnemonic is factually incorrect (the hand).

Yeah, this seems to be inline with what I’m saying.

Albeit, thereafter it seems we return to the question of which mnemonic is most effective. This brings up 2 quick last questions. In the above case, we are applying made-up meanings to phonetic components when that is more helpful for remembering the character than trying to link the phonetic component to the character’s exact pronunciation ([1.] which would almost always be the case?). And, 2., is this Level 3 depth?).

I’m not entirely sure what you’re asking here, but in my opinion, remembering pronunciation is much easier than remembering how to write the character. I rarely, if ever, rely on mnemonics to remember how a character is pronounced. That knowledge will also come more or less automatically as you learn more characters. So, using your words, I think that the phonetic component is (usually) already linked to the character’s pronunciation; you don’t need a mnemonic for that. If the link is extremely weak, as in 他 for example, I would just ignore the phonetic information and memorise it as if it were a meaning + meaning compound. Level 3 would mean that you do this, but you’re aware that this is for memorisation, not actual etymology.

Thanks for making this article a while back ago when I was learning Chinese characters!!

As an avid Outlier Linguistics dictionary user myself (and a bit of a nerd with researching character etymology often since it’s the main time I really enjoy doing!), I feel like I stand between the levels of 4 and 5 here since I just prefer to remember the characters I come across by logic and their real etymology rather than come up with a made up story myself. And because I guess I’m an advanced learner who wants to take learning Chinese characters seriously and know all of the real roles of each component.

Some examples I usually make for myself that I have of this are (and taking some characters from the article too):

– 美: A man (大) wearing sheep horns (羊): beautiful (I know 羊 is an empty component in this character but I personally like to use this mnemonic since it helps me remember the shape more.)

– 藥: Something made out of herbs (艹) that makes a person happy (樂) again: medicine (I know 樂 is sound component here but again, this is to help me remember it’s shape and the sound component this character has)

– 活: Water (氵) in the mouth (𠯑): alive, to live (Here, I’m aware that the sound component 𠯑, which is certainly commonly written into 舌 often, is used here so I use it instead of 舌 (shé) because I know that’s the real sound component)

As for some phonetic loan characters, I would usually try to connect the original meaning and the modern meaning together together in a logical way in something like this:

– 其: picture of a woven basket made out of bamboo

Original meaning: basket made out of bamboo (now written as 箕)

basket > ∆carries object inside > ∆object in a basket shows ownership > his, her, its

(Here I use ∆ in my system to show that it’s not a real meaning but rather to indicate some sort of logical connection between the original meaning and the modern meaning)

And yeah, that’s how I usually memorize characters learning their real etymology and maybe occasionally me coming up with some logical mnemonics that is related to the character itself. Thought I wanted to show you some examples to see if I’m doing this thing correctly at all 🙂

First and foremost, thank you for sharing detailed examples of how you memorise characters. I think this is interesting, but I’m sure that many other learners will find it interesting, too! You are pretty close to what I’ve been doing before, even though I don’t focus so much on learning characters these days. I think this approach is suitable if you have some interest in characters beyond merely being able to write them (and maybe if you’re after long-term retention and systematic understanding of the writing system as well). It’s a bit more detailed than I would recommend for the “average” student, but then again, that doesn’t matter. When it comes to memory and especially mnemonics, we’re all different. Your method might not work for somebody else (perhaps someone less interested in characters in themselves), but that’s not a problem for you! I think it sounds like you’ve found a great approach. I think it fits pretty well around level 4 according to the article.

Would a level 5 understanding be easier to achieve if someone learned with a filter that turned every 熊 into 能-over-大 or every 朕 into 舟 next to 火-over-廾? How weird would spelling such characters look to the average native?

I see how it might be odd to spell gœese plural of goose or strœngth for the strong, (analogical spellings of English umlaut that I made up) but I know that myce lyce and kyng are etymologically more correct than mice, lice and king (historical spellings).

I don’t think spelling is a good analogy here, but I think I understand what you mean! As mentioned in the article, I don’t think that a deeper level of understanding is always better. Most people don’t learn characters just to learn characters, so there’s always an opportunity cost. It would certainly be easier to learn if you have the information readily available, but the filter you mention would be incomprehensible without commentary anyway. It also would directly impede your ability to read modern Chinese, which is after all what most people are after!