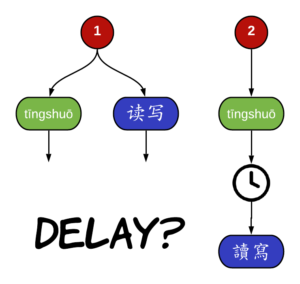

One of the most hotly debated topics in Chinese language pedagogy is the question of when to introduce Chinese characters. As a student, should you learn Chinese characters from the very start, in parallell with the spoken language, or should you delay the learning of Chinese characters and focus on the spoken language first?

One of the most hotly debated topics in Chinese language pedagogy is the question of when to introduce Chinese characters. As a student, should you learn Chinese characters from the very start, in parallell with the spoken language, or should you delay the learning of Chinese characters and focus on the spoken language first?

And if you delay learning characters, then for how long should you delay learning them? The delay can be very short, and relevant only for the content you’re studying.

For example, you can first listen to a dialogue, then talk about it, and then finally read the transcript and learn to write the characters. This is very different from delaying character learning for months or even years, becoming fluent in the spoken language before even starting to learn the written language (that’s what native speakers do, of course).

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to this article:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many more!

Should you learn to speak Chinese before you learn Chinese characters?

Another approach is to treat the written language as a completely separate entity, that could be learnt either in parallel with, after or even before the spoken language. Such an approach acknowledges the fact that something that is easy to say is not necessarily easy to write, and if you learn to write what you learn to say, the learning curve will be very steep indeed.

Compare starting with writing characters like 我, 你 and 是, which are all extremely common in spoken Chinese, with starting with basic building blocks first and gradually building up to more complex and irregular characters.

These types of approaches are very rare in formal education, and in this article, I will focus mostly on the timing issue, rather than whether or not you should learn to write the same words you learn to say. It’s worth noting, however, that the character course I’m currently building for Skritter uses this approach.

If you’re more interested in how to learn characters rather than when to learn them, I suggest you head over to this article instead:

To delay learning Chinese characters…

The reason the question of delaying character learning is a hotly debated topic is that it’s possible to argue either way, depending on your own opinions about the meaning and purpose of learning Chinese.

It’s easy to argue that writing should be delayed for the simple reason that it takes an awful lot of time to learn characters, and if you’re supposed to learn to write everything you learn to say, you will make very slow progress compared to students learning any other language, except Japanese. Besides, the spoken language is the real essence, the thing that makes us human, whereas writing is an artificial construct.

…or not to delay learning Chinese characters

But it’s also easy to argue the opposite and say that the written and spoken language are intertwined and that you can’t really say that you’re learning a language if you only focus on one side of it. Are you learning Chinese if you don’t learn the characters?

While I have nothing but personal experience to back this up, I have a feeling that native speakers who teach Chinese fall into this category more often than non-native speakers.

Some people also claim that Chinese can’t be understood without the writing system, claiming among other things that communication would break down if Pinyin (a proxy for spoken language) was used instead of Chinese characters.

Regardless of the general validity of such claims, it’s nonsense if we’re talking about the majority of people who learn Chinese as a second language. It’s perfectly possible to become fairly advanced in a language without knowing how to read and write, even if this comes with some problems of its own (more about this later).

Delaying Chinese character learning: A tricky question

The debate is further complicated by the fact that it’s almost impossible to do empirical research to prove who’s right, because there are so many variables involved. How long is the delay? What is the purpose of the program? Who are the students? Who’s teaching them? How are they being taught? And so on.

For an overview, see Ye (2011) whose dissertation strives to answer this question and has a comprehensive overview of the literature. For those who want to read more, I have added more articles to the reference section at the end of this post. One thing most people seem to agree on is that delaying character learning is great for developing spoken proficiency, but this ought to be fairly obvious.

Yes, you should delay character learning one way or another

In general, I think it makes sense to delay learning characters in favour of developing the spoken language first. That doesn’t have to mean that the entire process is delayed for months or years, just that I think you make sure you have a solid foundation in the spoken language before starting to learn characters seriously.

In general, I think it makes sense to delay learning characters in favour of developing the spoken language first. That doesn’t have to mean that the entire process is delayed for months or years, just that I think you make sure you have a solid foundation in the spoken language before starting to learn characters seriously.

The problem with learning characters is that it takes too much time, and that it will slow down your learning. The writing system is of course one of the main reasons that learning Chinese is difficult, and if you remove or at least postpone the introduction of that obstacle, you can learn the language at several times the speed.

You also free up time to use in more important areas. Spending time learning characters instead of mastering pronunciation is a really bad idea, and one you will regret later. Doing the opposite, neglecting character learning for some time until you’ve grasped pronunciation, has no serious drawbacks at all.

If you can already speak basic Chinese, learning the writing system becomes much easier as well. You now have those pesky tones and tricky initials and finals under control, freeing up your mental capacity to tackle Chinese characters. Furthermore, there’s lots of research in support of phonology playing a role in reading Chinese, even when reading silently (see for example Ziegler et al., 2000).

Reasons for learning Chinese characters along with the spoken language

That being said, there are several reasons why you might want to learn characters in parallel with the spoken language anyway, or at least why you might not want to delay learning characters for too long.

That being said, there are several reasons why you might want to learn characters in parallel with the spoken language anyway, or at least why you might not want to delay learning characters for too long.

I still don’t recommend that you learn to write everything you can say, but rather that you put significant effort into both areas at once. If you put the same amount of effort into both, your reading and writing will still lag far behind your listening and speaking.

Learning Chinese characters in parallel with the spoken language makes more sense in certain cases:

- If you’re not learning Chinese in an immersion environment, it can be difficult to find materials that support learning without using characters at all. Sure, you can find a few people to speak with, a tutor, a textbook and some podcasts, but without someone to guide you, it will be very difficult to rely only on the spoken language. If you study in an immersion environment or have people around you who can help you and talk to you in Chinese on your level, focusing only on spoken Chinese is more doable.

- If you study Chinese anywhere near full-time, you might find it difficult to spend all your time talking to people or listening to them, especially if you’re an introvert. Sure, you can find learning materials using only Pinyin for reading (or use tools to convert characters to Pinyin), but this is hardly practical. It will be easier to make the most of your time if you can spread the time over completely different areas, simply because it’s more varied and stimulating. This is a matter of time quality.

So, the bottom line is: Yes, you should delay character learning, at least until you have a good grasp of basic pronunciation. This doesn’t mean that you should learn zero characters, it just means that learning characters shouldn’t take up a large proportion of your study time. Later, you can ramp up character learning as much as you want, depending on your goals for learning Chinese.

Short-term delays: Reception before production

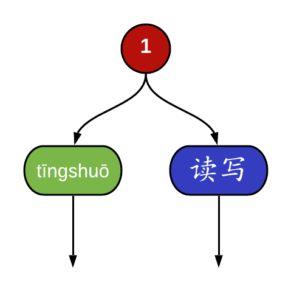

Even if you are learning the spoken and the written language in parallel, as most of us do, you can still sequence the learning in a way that emphasises the spoken language first, and makes sure that reception comes before production. In essence, that means:

- Listen and understand before trying to learn how to speak and make yourself understood.

- Read and recognise characters before learning to write them on your own.

This results in a sequence that looks as follows:

Listening → Speaking → Reading → Writing

Depending on what software you’re using for vocabulary learning and reviewing, this can be handled in different ways. Anki is very flexible in this regard, so I will use it for this example, but you can achieve similar results with other software too.

In theory, each word you learn can have four different flashcards:

- Listening – Audio on the front, the rest on the back

- Speaking – Definition, cloze sentence or picture on the front, the rest on the back

- Reading – Characters on the front, the rest on the back

- Writing – Definition, cloze sentence or picture on the front, the rest on the back

If you want to learn a bunch of words, such as key vocabulary from a story, you then go through the sequence in order. You add all four cards for each word, but you suspend all except the listening card. You then go through those words for a few days or weeks focusing only on listening until you feel comfortable with them, after which you activate the speaking cards and have a go at them. You then move on to reading and writing, although you can of course treat the spoken and written language separately here if you prefer.

For details about how to set up audio flashcards, please refer to this article:

Free and easy audio flashcards for Chinese dictation practice with Anki

Make learning easier by focusing on reception first

This approach is good because it eases you into speaking and writing. It’s very hard to know how to say things correctly if you’ve never heard them before, and the same is true for writing something you haven’t seen enough. This is especially true for beginners and especially true for pronunciation!

To make the most of this approach, you should be at different stages in the cycle for different words, so you don’t take a batch of words and see them through the whole process before you start with the next batch. Instead, you might have one set of words at each stage, adding a new set only when another set exits the process (nothing ever really ends, of course, but rather moves into long-term retention mode).

If you want to do this in class without your teacher’s explicit support, it means you have to start listening and reading ahead of time, making sure you’re at least a few weeks ahead of your classmates, focusing on listening and reading before you’re forced to deal with speaking and writing.

Sadly, many Chinese teachers force you to say things immediately after hearing about them for the first time. Here is a sentence pattern, it works like this, here is one example, now make your own sentence!

A simpler and more natural approach

Another way to use the same principles, but without having a mechanistic approach to vocabulary acquisition, is to simply focus a lot on comprehensible input (listening and reading), then make sure you recycle content enough before you try to do anything active with it.

For example, you listen to a story many times before you start figuring out how to use the words in it by talking about the story with a friend or tutor, or you select which Chinese characters to learn to write by hand by choosing those that you have already seen many times in your reading practice.

Conclusion

Sequencing is a very complicated question when it comes to learning spoken and written Chinese. I don’t pretend to have all the answers, but I hope that you have gained some insight into some of the questions in this area of learning Chinese and that this can guide your own approach.

As I said, one key factor is what the goal of learning Chinese is. If you’re the director of a Chinese program at a university, you will make this choice for all your students, but if you’re a student yourself, it’s up to you what you want to do, and you should choose whatever approach suits you and your ambitions best.

For most people who aim for long-term proficiency in both spoken and written Chinese, I think the case for delaying characters is very convincing.

References and further reading

Dew, J. E. (1994). Back to basics: Let’s not lose sight of what’s really important. Journal of the Chinese Language Teachers Association, 29(2), 31-46.

Knell, E., & West, H. I. (2017). To delay or not to delay: The timing of Chinese character instruction for secondary learners. Foreign Language Annals, 50(3), 519-532.

Packard, J. L. (1990). Effects of time lag in the introduction of characters into the Chinese language curriculum. The Modern Language Journal, 74(2), 167-175.

Poole, F., & Sung, K. (2015). Three approaches to beginning Chinese instruction and their effects on oral development and character recognition. Eurasian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 59-75.

Ye, L. (2011). Teaching and learning Chinese as a foreign language in the United States: To delay or not to delay the character introduction.

Ziegler, J. C., Tan, L. H., Perry, C., & Montant, M. (2000). Phonology matters: The phonological frequency effect in written Chinese. Psychological Science, 11(3), 234-238.

13 comments

I’ll add this as a comment as it is related to the topic, but not really relevant for most readers. This area, i.e. the relationship between spoken and written Chinese, is one the curriculum for secondary education in Sweden gets right. The general principle is that the written language is allowed to lag behind the spoken language.

This doesn’t mean you skip characters entirely, not even the first semester, it just means that as a teacher, you can be highly selective when it comes to which characters to teach. Other languages and most other curricula for Chinese do not allow for this, meaning that if the teacher follows the curriculum, students have to learn to write everything they can say.

Cool article! I have been learning Chinese for 2 months now and I am debating whether to spend the copious time needed to write the complex characters. I can do the basic radicals and I know how stroke order works. I don’t think it is worth it since I am working full time. I feel the time should be spent on oral work and learning the characters more. I feel like you would agree with what I read here. Any advice? Thanks!

Hello,

This is Jennifer. I used be to a Mandarin teacher from Confucius Institute. And I really would love to express my sincere appreciation to your dedication to Mandarin teaching.

I read some of your aticles about Mandarin teaching and learning and get inspired by it.

As for the topic you proposed, should you learn to speak Chinese before you learn Chinese characters. My opinions are as follows:

1. Learning Chinese characters is a must for beginners. Chinese in terms of its written form is a logographic language which is actually a very interesting thing for most learners around the world. It is also a good entry point to know the etymology of Chinese character when starting to learn Mandarin.

2. Learning Chinese characters will not slow down the language learning process but speed up its process since there are so many homophones in Chinese. By developing the ability of visually distinguishing and recognizing Chinese characters at the very beginning can lay a good foundation for future leaning.

3. Speaking alone cannot sastify all the communicative needs here in China. Pinyin is seldom used in our daily life. However, you can see Chinese characrs everywhere.

4. There is shortcut to every language learning, we can learn to speak within a short period of time with the Pinyin. But if the course designed to also give studetns access to Chinese characters will make this shortcut more effective.

5. It is very important to plan the couse based on students’ learning goals and learning habits. Some of my adult students even told me that writing Chinese characers and memorizing Chinese characters are way easier and more interesting than merely learning pinyin alone.

I hope my opnions above will also give you some insights about Chinese learning. Should you have any questions, please let me know via my e-mail zhifengwang@outlook.com

Hi,

Thank you for posting your thoughts on the matter! You highlight a few things I didn’t address directly in the article (mostly because it was already a bit too long), so I think this is a good opportunity to address some of them. I’ll respond argument for argument:

I’m not saying that beginners should not learn characters, only that the emphasis should be on the spoken language, especially pronunciation. Characters being interesting is a reason to learn them, but doesn’t really change the overall argument as I’m not claiming that beginners should not learn characters at all.

I don’t think this is true if you consider progress in the spoken language only, because writing takes up a large proportion of the available time and not bothering with it for some time frees up so much time that can be spent on the spoken language instead. Most university students I teach who are required to learn both in parallel complain that they spend almost all their time writing, which is the reason their speaking and listening falls behind. This also matches my own experience and that of almost every other student I’ve talked to, as well as all research I could find on the topic (see Poole & Sung, 2015; Packard, 1990; and Dew, 1994 for example).

As for homophones, that’s mostly a problem on the syllable level, not on the word level. How many homophones can you come up with that a beginner would run into? And even though there are homophones, I don’t really see the problem. If we compare with English, the sentence “I want to be there” consists of only homonyms (“eye wont two bee their”), and yet no one would say that this sentence has to be written down to be learnt.

I do agree that this becomes a problem later when character-level (and therefore syllable-level) knowledge becomes important, such as for figuring out near synonyms or abbreviations of various kinds, but none of this is relevant for beginners.

No one has claimed that it would! This article is not about whether or not to teach characters, it’s about whether or not to delay character learning a bit to focus on the spoken language first.

I agree that characters should be taught, but again, the article is about delaying character learning, not getting rid of it.

This, I think, is the most important argument against delaying character learning for too long. Many students, not just adult students, choose to learn Chinese precisely because they like the characters. If you then tell them, sorry no, you have to wait six months for that, some of them are going to lose interest. In these cases, I would advocate a selective approach where you teach Chinese characters and how the writing system works, but you still don’t require them to learn to write everything they can say.

My point is that you can satisfy the desire to learn Chinese characters without going all-in and requiring them to learn to write everything.

Best wishes,

Olle

-In theory, each word you learn can have four different flashcards:

Listening – Audio on the front, the rest on the back

Speaking – Definition, cloze sentence or picture on the front, the rest on the back

Reading – Characters on the front, the rest on the back

Writing – Definition, cloze sentence or picture on the front, the rest on the back

Should the flashcard (Anki for example) be set in a way that for Speaking it expects me to pronounce the character and check my pronunciation? Is that even possible in Anki?

I would like to know something:

I’ve been learning for three and a half months, and from day one my teacher has been exposition us to characters. As we progress, she uses less and less pinyin, and sometimes only when introducing a new word or a new character, and I love her approach.

I do a massive amount of listening, reading, shadowing, and flashcards on my own, and I’m now able to read level 1 graded readers and understand a lot of what’s said in children’s tales and such. So far, I’ve put zero effort into handwriting, but I do type a lot on my computer and phone (doing internet searches, leaving comments on social media, writing sentences and words that I want to study later).

So, it confuses me a little that you don’t make a distinction between handwriting, or rather, that you don’t really mention typing as a form of writing, which is really a separate skill. To me, this approach of only using electronic devices to write almost from day one has proven effective, and I don’t feel like it’s making me compromise the other parts of my learning.

I’m a professional wishing to remotely communicate with coworkers in China, both via email and video conferencing (mostly email, though), so does it make sense where I’m coming from? What are your thoughts?

Love your articles, by the way!

Can i do the opposite ???

You advised against this method (in another article) because it usually neglecte the phonetic components in most Chinese characters.

I’m learning characters by their phonetic components (using the Outlier dictionary).

So i guess there’s no reason why i shouldn’t learn Chinese by learning the written part first, right ??

Particularly since if i did so, it will make it easier for me to focus on the tones (when i start learning spoken Chinese later on),, because by then, i will be familiar with many of the syllables/toneless pinyin.

I’m only fascinated by the characters, so i hope this method works.

Thanks.

If your main goal is to read, then you can certainly do that! I’m mostly talking about people who want to learn all aspects of the language here. Tones aren’t very important when it comes to characters, because they are rarely preserved in phonetic components anyway (in fact, Chinese hasn’t always been tonal either, so many characters were created when there were no tones).

Yes, my primary goal is to master reading.

Thanks a lot for your answer.

When I started to learn Chinese I took a very unorthodox approach. I studied characters for years, before beginning to study actual phrases in written Chinese, and before beginning to speak or to pronounce, or even to listen spoken Chinese.

For various reasons this approach did not work for me. One reason is that I ended up having to imagine clearly every single character in my mind while speaking, which is impossible. This approach delayed for years my acquisition of all the other skills needed to speak a language. I had to painstakingly “deconstruct” all that I had learned and I had to begin again from zero. In the short term, I was able to read a novel in Chinese after one year of an intensive course in Chinese (focused more on reading and writing than speaking), but I was not able to buy apples smoothly in the market (this example is real). In the long term I am not even sure that this approach helped to recognize more characters.

Don’t try this at home.

Thank you for sharing! I think the most important thing is to study according to one’s goals. If one wants to read and/or write, then focus on the written language; if one wants to listen/speak, then focus on the spoken language. If a balanced competence is desired, then mix both. This ought to be obvious, but far too often, courses and teachers impose a syllabus very heavy on reading and writing, even if students want to learn the spoken language too.

I just became interested in Chinese TV dramas but have had to stop them often in order to read the English translation. I would like to learn to understand the spoken language so I can watch the dramas without bothering with closed caption English translations.

Since I am 70 years old and never likely to travel to China I don’t believe I have the time or inclination to learn to write the characters. Thank you for your thoughts.

How much do you understand right now? I generally recommend that you spend a majority of your time with materials you can mostly make sense of unaided. You don’t mention how much Chinese you know already, so it’s hard to give more specific advice. You can safely ignore characters up to at least an intermediate level.