I think most languages have a saying or an idiom meaning that teaching is a great way to learn. This article isn’t about actual teachers and students (so don’t think that you need to be a teacher to benefit), but rather about a certain way of remembering and/or understanding things that are difficult and complicated. Studying Chinese, I think idioms and grammar are two good examples, but before we look closer at them, I’ll give you a background story.

Learning idioms by explaining them

Last year, I was preparing for a test and decided to learn quite a large number of idioms (成语) because I knew that some parts of the exam would be loaded with these and it would be hard to pass without having passive knowledge of them. Therefore, I generated a list of slightly more than one thousand idioms and learnt them over a relatively short period of time (less than a week). This was doable because I knew most of the characters in these idioms already, otherwise it would have been impossible (read more about learning individual characters here).

Even though I think idioms are interesting and I plan to write something about learning them in the future, the idioms themselves aren’t the topic of this article. Instead, I want to highlight something I noticed much later. I reviewed a number of these idioms together with a few friends (who don’t speak a single word of Chinese) and whenever I encountered an idiom I didn’t know, I checked the answer, gave them the four characters (translated into Swedish) and let them guess what the idiom meant. Then, I explained what it really meant and what the connection between the underlying characters and the surface meaning was.

The thing is that now, months later, I see a pattern. All those idioms I explained to my friends in Swedish are clear and vivid in my mind and I almost never fail them in my flashcard reviews. Other idioms from that batch have much higher failure rates. Now, the obvious explanation is that I simply spent more time learning these idioms and therefore I remember them better, but I don’t think that such an explanation is adequate (I spent only perhaps 30 seconds with an idiom, which isn’t much). Instead, I want to suggest another solution.

Explaining what you’re doing really helps your own learning

There is nothing truly controversial with the above statement, but have you really tried it? What I mean is that yes, time spent matters, but how you spend that time matters even more. If you spend 30 seconds writing a 成语 over and over, it is probably wasted effort. If you spend that time explaining to your friend why four characters combine to form an idiom, well, then that seems to be very effective indeed, at least in my case. Explaining something, you approach what you want to learn in a different way and create new links to other things you know. Simply repeating something isn’t always the best, even if you’re wise enough to use spaced repetition software.

Another reason teaching or explaining is so useful as a learning method is that you expose your own weaknesses. If you’re telling someone else about an idiom, you really have to know the component characters and the story behind the idiom, you can’t just say “oh, yeah, I know this” and skip to the next flashcard (and then only later find out that you actually weren’t sure about the last character). Explaining something is a good way of making sure that you understand the concept or idea yourself.

Teach your imaginary friend, teach yourself

Most of us don’t have friends sitting around all day, eager to hear us drawling about learning Chinese, but I don’t think that’s necessary. Explaining something to your imaginary friend is good enough (i.e., explain to yourself). To make this feel real and to ascertain that what you say makes sense, you should do one of the following:

- Actually explain the words aloud, imagining that you have a person in front of you

- Write the explanation down or draw pictures explaining it

This is a very active way of learning and/or reviewing which is useful whenever you encounter something you find difficult. It’s probably not very efficient for learning simple words, but it works well for leeches (i.e. flashcards that just refuse to stick in your memory and drain time and energy).

The Feynman Technique

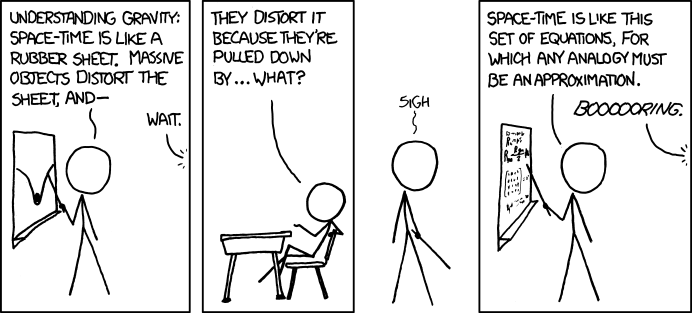

This concept is similar to what Scott Young calls “the Feynman Technique” (watch his explanation on YouTube here). His idea is basically that you should reduce the concept you want to learn into manageable chunks that can be explained using everyday language you understand (in Chinese, this would mean using words you actually know, probably in your native language). In other words, you explain concepts as if you’re introducing them to a child or a complete beginner.

Image credit: xkcd.com

I mentioned grammar in the introduction and this is where I think this kind of thinking works best. If you encounter grammatical concepts you find hard to understand, write them down and explain them as if introducing them to someone who knows nothing. If you’re successful, you will have solidified a mental model of the grammar you’re trying to learn, and if you fail, you will at least know where you need to improve. Go back to your teacher and/or reference book and try again. Even if you don’t arrive at a perfect model (there might be no such thing), this process still helps you understand how the language works.

Mental models and learning

As I have argued elsewhere, learning a language is all about adjusting mental models of how the language functions. This means two things:

- You need exposure to real language (reading and writing, but also being corrected by others) to see if your model matches reality

- Models are by definition not the thing they represent and will therefore not be 100% accurate; you need to update them continuously

The Feynman Technique is really nothing more than an explicit way of enhancing and strengthening the models you have. The models are always there, but by writing them down or saying them aloud, you will be able to either understand better what you already know or you will find gaps or flaws in the models you currently have, which will prompt you to investigate further and update your models according to the information you find.

No substitute for actual teaching

Having taught both Chinese and English, I find that actual teaching is one of the best ways to learn. This is not to say that imaginary friends aren’t useful (they are), just that real students are better. Having taught Chinese pronunciation to classes of complete beginners several times, I know much, much more about it than I did before. This isn’t only because I’ve spent more time reading about it, but also because I’m forced to take implicit knowledge and make it explicit.

Also, a drawback of explaining things to yourself is that you’re probably not critical enough and you sometimes understand what you yourself are saying/writing, even if it wouldn’t make sense to a real beginner or an actual child. Students will ask lots of questions when they don’t understand (most of these questions are very hard to predict), which is a wonderful way of learning more.

Still, explaining to ourselves as if instructing beginners is very useful. Generally speaking, the more complicated the topic is, the better this method works. Give it a try next time you run into something you find hard to learn!

Finally, I’d like to ask a few questions:

- Have you noticed positive effects of teaching Chinese (either as a real teacher or casually)?

- Have you tried other ways of making implicit knowledge explicit (I can come up with some, but I’ll save them for the newsletter)?

- Have you any other ideas or advice about implicit/explicit knowledge and/or teaching?

3 comments

These comments have been manually retrieved after a server crash:

Emma: Learning and teaching are also seperate parts of the brain. As is shown in many studies, if you activate more than one part of the brain while learning something that information is more bound to stay. In your case, in order to learn you didnt have to use your analytical skills, you just had to store information, but to teach you hade to break down the idiom in tasks, thus using different parts of your brain.

By saying it out loud, you use your speak-centra (or whatever the word is) and then you interact and you process the information you hear from your friends, thus using a much larger portion of your brain than in the first case of reviewing the idioms and writing them (two things).

In your first example you aldo had to translate them word by word – and translate the meaning of the idiom, which is yet another process.Interesting article! (ie MISS YOU 🙂

February 26th, 2012 at 10:38

Sara K.: It never occurred to me to use drawing to help me learn Chinese … but now that you mention it, that seems like a lot of fun. Next time I go after leeches, I will squash them with doodles.Speaking of doodles, I remember there were a couple classes in college where I drew doodles over all of the tests. Of course, I also answered the questions regularly, but I added the doodles because I felt like it, and I knew the teacher wouldn’t dock my score. Well, not only did the teacher not dock my score, the teacher said that the doodles actually improved my score because there were times when my written answer was unclear, but he could tell by the doodles that I understood the concept.There is one doodle I still remember years later. The question had something to do with par cans. I doodled Jimi Hendrix’s guitar and Jimi Hendrix’s par can. Whereas Jimi Hendrix’s guitar was broken, Jimi Hendrix’s par can was as good as new. A par can is type of bright light which was originally used by the army in WWII, but after the war, because the military did not need as many, they were quite cheap, as well as quite durable. They were particularly popular with rock bands because they were so inexpensive and difficult to break – which is why Jimi Hendrix’s par can was still in good shape. If I hadn’t made that doodle, I’m not sure I would have remembered that much detail about par cans.

February 26th, 2012 at 13:31

Hugh Grigg: Olle I love your posts! Yeah I agree so much that getting actively involved with what you’re learning makes such a difference. It’s actually worth spending quite a bit of time with individual characters, say, because then they’ll stick and you won’t waste time in future reviewing them repeatedly (John Pasden described this, actually: http://www.sinosplice.com/life/archives/2008/06/30/ode-to-heisig-and-rtk.It)’s also a flaw with SRS, in a way. It’s tempting to think that you can just load stuff into the SRS and learn it, but actually it’s incredibly difficult to internalise stuff long-term without a deeper context and active engagement. Seems natural learning out in the field wins every time, no matter how much you’d like technology to make it simple.

February 27th, 2012 at 14:09

vermillon: A real coincidence! As part of my 2012 language programme, I bought some notebooks to rewrite the grammar I’m learning in Korean. I read some grammar books that explain some sentence structures, the use of some prepositions etc, but I make a point of rewriting it my own way in the notebook, with my own examples and understanding… and it works well. I didn’t do this consciously though, I just felt the need to do it.And of course, I completely agree with your post. A few examples:

-During my MSc degree, I’ve asked a teacher about a topic I didn’t quite get, and he told me “I only really understood this topic after I had taught it the second time to a class of students”.

-Also, during that year, what made me understand the concepts of the courses (and get a nice row of As) was that some of my classmates were not very good at those courses and I spent quite a lot of time explaining them the concepts of those courses in simpler way. It has had 2 very positive effects: 1) my understanding of the courses was much better later (sometimes it even went from “I don’t understand at all” to “I understand fully”) and 2) my classmates also had a better understanding… I guess that’s what you call a win-win situation.

-Finally, during my engineering studies, I’ve taught maths to quite a lot of high school students: this helped me keep a fresh knowledge of (high school) maths, and made my reasoning much clearer.Now I should try to find how to apply this to language learning… coming to think of it, when you teach maths, there’s a rather limited amount of “raw data” to know, and the rest is reasoning… but when learning languages, you do need “tons” of vocabulary… finding explanations for all of them seems rather difficult. I’m curious, how many hours did you spend learning those 1000 idioms in a week?

February 29th, 2012 at 12:50

Jonathan: This is very interesting to make the distinction between simply time spent and the quality of that time spent when learning something.I find that speaking Chinese with other Chinese learners below my level (who do not speak English) can be very helpful. I don’t mean actually teaching them explicitly. But I find when I speak to them and slow my speech and am more conscious of my language, pronouncing everything very clearly so to be understood – this exercise seems to solidify or consolidate my basics.Seems similar to teaching – though not explicitly so, my brain goes into a sort of teaching mode. I do find myself guiding the listener along in some fashion.

March 2nd, 2012 at 04:47

Sam Reeves: Traditionally in Asia teaching is considered the second part of the learning process. So yes Olle, you’ve definitely stumbled upon a truism. I’ve heard this more around the martial arts scene in my own country and China, more than most other subjects for some reason.I think there is also a saying about it, the exact form of which escapes me at the moment but goes something like: ‘to be competent study, to be a master teach’.Teaching reaches a depth of understanding of the subject matter that makes it your own and leads to further clarity. This is one of the reasons why teaching is a very respected profession in China, as I’m sure you know. They understand that each individual that teaches may reach a unique level of understanding that can aid students growth and skill (and the overall culture).

I guess you could liken it to ‘letting a thousand flowers blossom’ (although I dislike to quote Mao). A thousand creates two thousand, two creates four… and on and on… hopefully with ever deepening insights.

Liked your article by the way. Clarified some thoughts I’ve had.

March 2nd, 2012 at 09:30

Olle Linge: @Emma: I will definitely think/read more about this. Do you have any recommendations for what to read? I’ll probably write an article about this, focusing on why it’s good to learn something five times in different ways rather than five times the same way.@Sara: Cool! I wish I could magically learn to draw. I’m too self-conscious to draw very ugly doodles. :)@Vermillion: Excellent examples, thanks. Regarding the idioms, I spent quite a lot of time, perhaps a total of 30 hours. This was a deliberate “can it be done” experiment; otherwise I would never dream of spending that much time in a week. 🙂

@Jonathan: Yes, I agree. I’m usually trying to avoid that situation, not because I think you’re wrong, but because I really enjoy the challenge of attacking material which really is too hard. I think what you describe is an excellent approach and way of thinking about other students which should make people more tolerant (I hope). Also, this article might be of interest.

@Sam: In a sense, I think teaching has to be the second stage, because if you don’t learn something first, you can’t teach it. However, we don’t need to separate the two stages with time counted in years. It’s perfectly okay to teach something you know even if you’ve only known it for a short time. Of course, if you want someone to pay you for doing it, then you need more, but that’s another topic altogether. 🙂

March 2nd, 2012 at 13:57

Sara K.: I’m not good at drawing myself, but I am willing to doodle shamelessly (just as I’m willing to speak Mandarin shamelessly).

March 3rd, 2012 at 14:45