So far in this series, we have looked at characters that started out as pictures, such as 女 (nǚ), “woman”, 子 (zǐ), “son; child”, and 马/馬 (mǎ), “horse”. Learning such characters often becomes easier by looking at the historical forms of the characters and learning about their origins.

So far in this series, we have looked at characters that started out as pictures, such as 女 (nǚ), “woman”, 子 (zǐ), “son; child”, and 马/馬 (mǎ), “horse”. Learning such characters often becomes easier by looking at the historical forms of the characters and learning about their origins.

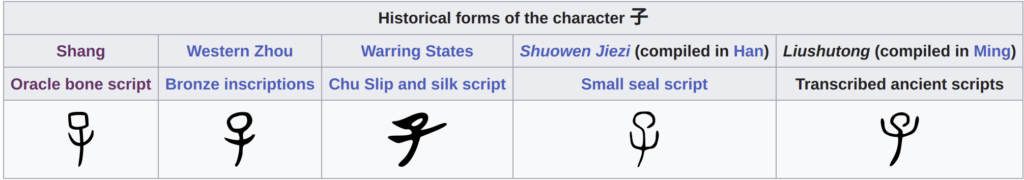

For example, 子 might not look like a child to you, but check out the historical forms from Wiktionary below. Once you’ve seen that, it’s easier to see the arms sticking out to the sides of 子 and thus also easier to remember how to read and write the character. We looked at many more such examples in part two of this series.

If this doesn’t work for you, it’s time to get creative! As long as you associate the shape of the character with its meaning, you’re okay, it doesn’t matter if you’re being true to the actual origin of the character.

For example, in part two, I created a mental image for 舟 (zhōu), “boat”, thinking of it as a submarine tower sticking up out of the water with two people in it and a periscope at the top. Obviously, this character predates the invention of submarines by thousands of years, so there’s no real connection between the two, but if that image helps you remember how to write this fairly common building block, that doesn’t matter!

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many other platforms!

Articles in this series (all have podcast episodes too):

- Part 1: Chinese characters in a nutshell

- Part 2: Basic characters and character components

- Part 3: Compound characters

- Part 4: Learning and remembering compound characters

- Part 5: Making sense of Chinese words

- Part 6: Learning and remembering compound words

Mnemonics are memory techniques to aid learning

Such aids for learning and remembering things are called mnemonics, and I will return to this later in this article. For now, though, it’s enough to say that mnemonics can be effective and that research suggests that coming up with your own mnemonic device is more efficient that learning from someone else.

This is probably because our brains are wired quite differently and what you consider easy might be hard for me and vice versa. Try searching for the character in question plus “mnemonic” in an image search and judge for yourself! Here are links to Google Images for the characters I mentioned above but didn’t explain or show images for:

Personally, I find most of these images next to useless. Many of them seem like someone has just taken an image of representing the meaning of the character and then simply pasted the character on top of it. But then again, if you see an image that just clicks for you, that’s great, even though creating one for yourself is probably better.

I’ve written more about mnemonics for learning characters here (for specific articles about mnemonics for pronunciation, abstract character components and so on, just search for “mnemonics” here on Hacking Chinese):

Not all Chinese characters are easy to learn, but most make sense!

In the previous article, we learnt that these pictographs are rarely used as stand-alone characters in modern Chinese, making up only a few percent of the total. That doesn’t mean that they aren’t important, though, because they still appear as components (or building blocks) in compounds, and almost all Chinese characters are compounds!

We also learnt that components can have different functions, such as indicating the meaning of the compound, such as both components in 好 (hǎo), “good”, consisting of 女 (nǚ), “woman” and 子 (zǐ), “son; child”. In most compounds, one component is included because of its pronunciation, such as马 (mǎ), “horse” in 妈 (mā), “mother”.

We also saw that some characters are just so chaotic that looking up their origin doesn’t seem to be all that useful, such as 因 (yīn), “reason; cause” or 他 (tā), “he”. Knowing that the 囗 in the first originally represented clothes and that 也 (yě) is the sound component in the second might be interesting and help you understand how characters work in general, but it won’t necessarily help you remember those particular characters. In fact, most educated native speakers don’t have a clue about why 因 looks the way it does, but they can still read and write perfectly fine!

My general advice to learners is to pay attention to components, especially those that appear often and especially those that offer clues to pronunciation (those that offer clues to meaning are often more obvious, it doesn’t take a PhD to note that 木 often appears on the left of characters related to trees). If you are interested, you can look this up, and if the information helps you understand the character, that’s great! If it doesn’t, then rely on your own creativity to come up with clever ways of remembering how to read and write the character. You shouldn’t feel that you have to learn the actual etymology of the character, but at least look it up in case it’s actually helpful!

So, to summarise, most characters you encounter are neither as easy as 好 nor as hard as 因 to understand. Most characters are like 妈, albeit sometimes with a less obvious sound component.

Character composition: How components fit together

We have now talked about compound characters a bit and you have seen many examples that all combine components in various ways. Sometimes they are put beside each other (好), sometimes on top of each other (骂), sometimes enclosing one another (因).

You now know enough about characters to see that this matters greatly. To break down characters into components and understand what roles they play, you have to split compounds the right way! You also need to know when to not split characters at all, as we saw in the part two.

The different structures actually have their own Unicode characters and can therefore be typed. Here they are (source on Wikipedia):

- ⿰ left to right

- ⿱ above to below

- ⿲ left to middle and right

- ⿳ above to middle and below

- ⿴ full surround

- ⿵ surround from above

- ⿶ surround from below

- ⿷ surround from left

- ⿸ surround from upper left

- ⿹ surround from upper right

- ⿺ surround from lower left

- ⿻ overlaid

In part two, I said that it’s okay to note that 鱼 (yú), “fish”, contains 田 (tián), “field”, but that you should not expect to gain any insight into this character by breaking it down like this. Likewise, for someone who knows characters, it’s obvious that 因 contains of two components, one inside the other, but a beginner might be tempted to think of it as a single image. It’s hard for me to say what it might look like for an uninitiated beginner if considered as an image, but maybe a wrapped up gift seen from above? A tent, perhaps?

Make sure you pay attention to character composition to identify the correct building blocks

Ignoring actual character composition is extremely bad for long-term learning. The reason is that if you think of 因 in terms of 囗 and 大, you have identified the correct components. These appear in dozens of other characters you will encounter in the near future. If you think of the character as a unit (a gift or a tent), you will not be able to use this for learning any other character.

Another example is the character 想 (xiǎng), “to think”. What do you think the structure of this character is?

There are three identifiable building blocks here, whereof we have learnt two already: 木 (mù), “tree”, and 目 (mù), “eye”, and the third one is 心 (xīn), “heart”. However, as you can see, there isn’t a character structure like that in the list above. That’s because this is the wrong way of breaking down the character. It’s supposed to be above to below and then the top part is then split left to right. So the whole character is actually 相 (xiāng), “each other; mutual”, and 心 (xīn), “heart”. This should also make it quite obvious that 相 (xiāng) is a sound component. I’ll return to this character again below.

The key takeaway here is that you can be as creative as you want, but do adhere to the actual structure of the character.

The true story behind a character is not always helpful

In an earlier article about this, I identified five levels of character understanding. I strongly suggest that you avoid levels one and two, but anything from three and up is perfectly serviceable. Here’s a quick overview:

- Inventing pictures that disregard composition and structure of characters – This is the worst, illustrated by the example of treating 因 as a gift wrapped in paper with fancy strings or maybe a tent. Another example would be to think of 吃 (chī), “to eat”, as a boy eating ice cream (see the picture in the preview below). This level of understanding is only suitable for very young children and people who don’t actually want to learn Chinese.

- Creating stories and associations that obscure functional components – The most common example of this approach is to think that all components as meaning components, so every time you see a character like 妈, you only think “woman” plus “horse” equals “mother”. Some students study Chinese for years thinking like this. Even highly knowledgeable people overestimate the prevalence of characters that are actually combinations of meaning components.

- Using superficial pictures while being aware of functional components – This is what I recommend that most students to do, and it’s what I’ve been advocating throughout this series. You should know about phonetic components and be conscious of them when you learn, but you can definitely use the superficial forms to boost your memory. For example, it’s fine to create a mental picture of a horse riding on your mother’s back if that image helps you remember how to write 妈, as long as you know that 马 is actually a sound component.

- Using superficial pictures and encoding functional components – This is a somewhat more elaborate method where you do the same as above, but you encode whether or not a component is phonetic in the image you create. Maybe envision the horse in the picture from above as being transparent and made of glass to remember that it’s not a meaning component. This is overkill for most students.

- Etymologically correct mnemonics with no shortcuts – On this level, you only strive to remember characters based on their true structure and the actual function of components. If 马 is only there for phonetic reasons, you shouldn’t think of a horse at all. I see little purpose in being this pedantic in your own learning and while it might help you learn more about the origins of characters, it’s likely to be detrimental to your capacity to learn new characters.

For more about each level, check out the full article here:

5 levels of understanding Chinese characters: Superficial forms to deep structure

Practical mnemonics for compound characters

Before we move on to words in the next article, let’s get a bit more practical. I’ve talked more about mnemonics and memory techniques in this article, but since we are talking about character compounds, I’ll show a few examples of how to remember characters effectively and usually with little effort once you know the components. These mnemonics are on level three on the scale above and is what I recommend most students to use. Like I said before, though, making up your own mnemonics is preferable, these are just ones I happen to find useful. I’ll also add some information about zooming out (looking at the character in the context of other characters or words), zooming in (looking closer at components) and panning (looking at similar characters).

Example 1: 秋 (qiū), “autumn”

Example 1: 秋 (qiū), “autumn”

This character is a left-right composition consisting of 禾 (hé), “grain”, and 火 (huǒ), “fire”. Both relate to the meaning of the character and are very common building blocks. The real etymology of this character is quite helpful, as it shows grain being burnt in the autumn, which is something that was done to get rid of pests. According to the Outlier Linguistics Dictionary of Chinese Characters, the character in its original form showed crickets being burnt. To make this more vivid, imagine yourself setting fire to a field of grain, ready for the autumn harvest. I also associate fall with t fiery colours, making the association even easier!

Zooming out: If you later come across the character 愁 (chóu), “anxious; worry”, which is much rarer, it’s easy to expand on this theme. It is in fact a phono-semantic compound (chóu and qiū are not that different), but it’s easy to remember how to write the character if you think of the worry or anxiety you feel when someone has burnt down the autumn harvest. Also, having “autumn in one’s heart” also seems like a somewhat poetic way of describing anxiety and sorrow.

Zooming out: If you later come across the character 愁 (chóu), “anxious; worry”, which is much rarer, it’s easy to expand on this theme. It is in fact a phono-semantic compound (chóu and qiū are not that different), but it’s easy to remember how to write the character if you think of the worry or anxiety you feel when someone has burnt down the autumn harvest. Also, having “autumn in one’s heart” also seems like a somewhat poetic way of describing anxiety and sorrow.

Example 2: 想 (xiǎng), “to think”

We looked at this very common character above because it’s a good example of why character composition matters. It’s a top-down composition, where the top part is itself a left-right composition, so if you try to understand this character by looking at all three components at once or by connecting one of the top components to the bottom one, you will fail.

After the first split, we get 相 (xiāng), “each other; mutual”, and 心 (xīn), “heart”. 相 (xiāng) should immediately stand out as a possible sound component (only the tone is different), which is also the real explanation. 心 is a reasonable meaning component, because even if we know today that thinking is done in the brain, not the heart, it has been common to associate thinking with the heart throughout different cultures in history.

Zooming in : 想 is more common than 相, so the odds are that you will need to learn this component as a separate character as well. It’s quite common, so it’s worthwhile! It originally meant to see something, or to compare, which was then extended to the more common usage today: “mutual; each other”. The components are 木 (mù), “tree; wood” and 目 (mù), “eye”. Both these relate to the original meaning, i.e. “to see” (an eye closely observing a tree, according to Outlier).

: 想 is more common than 相, so the odds are that you will need to learn this component as a separate character as well. It’s quite common, so it’s worthwhile! It originally meant to see something, or to compare, which was then extended to the more common usage today: “mutual; each other”. The components are 木 (mù), “tree; wood” and 目 (mù), “eye”. Both these relate to the original meaning, i.e. “to see” (an eye closely observing a tree, according to Outlier).

This leads us to an important point: While it often makes sense to zoom in, it’s not always the best way to invest your time. In this case, it was fairly easy and 相 will appear in other characters you’ll need to learn soon anyway, such as 箱 (xiāng), “box; case”, where it’s also the sound component. In other cases, though, it could be that the components are much less common. If you’re worried about this and want to stick to the bare minimum, wait until you see the same components reappear in at least one other character!

Example 3: 很 (hěn), “very; quite”

This is a very common word, especially in spoken Chinese. Beginners encounter it on day one, because it’s used to link nouns and adjectives in phrases like 你很美 (nǐ hěn měi), “you are beautiful”, and 我很高 (wǒ hěn gāo), “I’m tall”, when it’s best translated as just “to be”.

The character is a left-right composition, with the left part contributing to the meaning. 彳 is a fairly common character component and is the left part of 行 (xíng), which here means “to walk” (the original meaning and picture is that of a road intersection). You can often see this in characters related to action or motion, and it’s more that worthwhile to learn.

The right part is 艮 (gèn or gěn), which is rarely used on its own today, but had the original meaning of “to look back” (it almost looks like legs with an eye 目 looking back). It is clearly a sound component in 很 (hěn), “very; quite”.

To illustrate which options you have as a learner here, you could just use the basic meaning of the two components and visualise a picture or make up a story. Can you make up a story with 彳, 艮 and 很? I think you can! Leave a comment below if you think you have a good one!

The other option is to dig a little bit deeper and learn about the other things I mentioned above. This will obviously take longer if your goal is to only learn the character 很, but it will pay off handsomely in the long run. Did you know that the character 艮 appears in a dozen other common characters where it’s also the sound component? Most of these start with h- or g- (two very similar sounds) and they end in -en or -in (also quite similar).

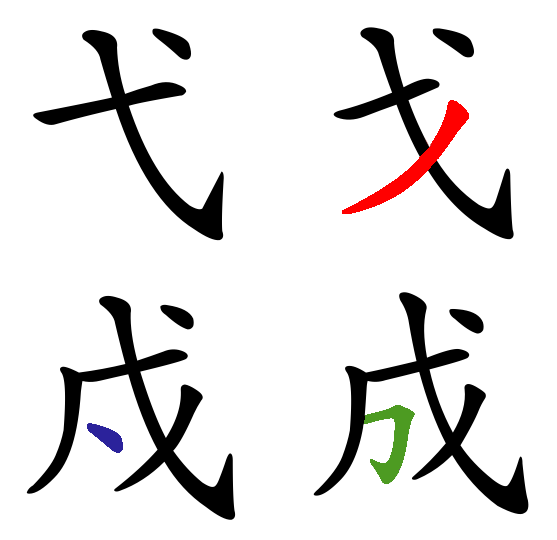

Panning: This character is also a great example of why panning is essential. A problem with learning Chinese characters that becomes more apparent the longer you study (see The real challenge with learning Chinese characters) is that it becomes increasingly likely that you mix characters up. We just looked at 艮, but you might have noticed that we also have 良, which is visually very similar. I don’t do this to scare you (because there’s an easy solution), but how are you supposed to remember if there’s a dot or not in these characters, which are all in use today?

Panning: This character is also a great example of why panning is essential. A problem with learning Chinese characters that becomes more apparent the longer you study (see The real challenge with learning Chinese characters) is that it becomes increasingly likely that you mix characters up. We just looked at 艮, but you might have noticed that we also have 良, which is visually very similar. I don’t do this to scare you (because there’s an easy solution), but how are you supposed to remember if there’s a dot or not in these characters, which are all in use today?

- With dot: 娘, 浪, 狼, 莨, 阆, 琅, 稂, 锒, 粮, 蜋, 酿, 踉

- Without dot: 艰, 限, 垦, 很, 恨, 狠, 退, 垠, 哏, 恳, 根, 痕, 眼, 银, 裉, 跟

The answer is that you shouldn’t think about them as “with dot” or “without dot”. They are sound components in all these characters, and indeed, all the ones without a dot (艮) have similar pronunciation: h- or g- plus -en or -in. Those with a dot (良) are based on the character 良 (liáng) and almost always end in -iang or -ang. Just by knowing this ,you can easily remember how to write these characters! I wrote about this in more detail here:

Learning Chinese character compounds quickly and efficiently

You now know enough to be able to learn Chinese compound characters quickly and efficiently. Of course, identifying and learning the building blocks takes time, and understanding how compounds work also take time, but this is something you’ll be able to learn gradually now that you know the basic principles. Of course, I haven’t explained everything there is to learn about characters in this series, but I have given you enough to avoid the most common problems!

Another process that takes time si to figure out how your memory works. There are very powerful ways of associating objects with each other that will form long-lasting memories, and as I’ve argued elsewhere, remembering is a skill you can learn. This is good news, because it means that there are many things you can do to improve your memory, but it also means that this requires practice.

I have shown you the basic building blocks, some principles for how they are combined and a few hints at how to do that in your mind in such a way that you will remember it later, but in order to learn hundreds or thousands of characters, you need practise all of this in close contact with the actual language!

This series doesn’t end here either, because there is at least one more level to explore: multi-character words. Modern Chinese has a strong preference for two-syllable words, such as 中国 (Zhōnggúo), “China”, which means that they are expressed by combining two characters, so often combinations of compounds! Some words are longer than that, too, such as 星期日 (xīngqīrì), “Sunday”,but there are also many characters that are used as words on their own, such as 我 (wǒ), “I; me”.

Since words are what people actually use to communicate with each other, no discussion of the Chinese writing system would be complete without discussing how they are formed and how to learn and remember them, so that’s what we will do in the next part of this series:

https://www.hackingchinese.com/the-building-blocks-of-chinese-part-5-making-sense-of-chinese-words/

11 comments

there is*n’t a* character structure like that in the list above.

Thank you for pointing out the error; I’ve fixed it now! 🙂

Something I’ve noticed, but have never heard described, is that some components seem to have a secondary pronunciation when used as a component. For example, 京 is pronounced ‘jing1’ but it appears in a lot of characters that are pronounced ‘liang’ (凉, 晾, 谅, 椋, 辌) – so many in fact that I have to believe it’s a pattern of some sort, yet I’ve never seen 京 given that pronunciation even in contexts that include alternative/rare pronunciations. Are you able to shed some light on this? Are there are components that systematically represent a particular sound or meaning only when used as a component that learners should be aware of?

Other times it turns out there is a pattern if you dig a little. For example 月 often appears in words relating to the body (胸,脑,脸,胡,背,etc). I noticed this but I but I couldn’t figure out why, until I read somewhere on this site that 月 can also be the component version of 肉 (月肉旁)。I really feel like this is something I should have know earlier, but when I looked back a lot of dictionaries and other resources I had been using explicitly refer to 月 instead of 肉 when breaking down the characters into components, which is quite misleading. I think knowing the alternative semantic meaning and origin of this component would be helpful to most learners, and makes me wonder if there are other examples of this that I haven’t picked up on.

Regarding your first question, I’m not an expert in these things, but the first thing that comes to mind is that the people who created these characters didn’t speak modern Mandarin, they didn’t even speak Mandarin. Changes in the spoken language across dialects over hundreds of thousands of years have resulted in many sound components not being very consistent. If you’re interested in this, I would read up on the phonology of Middle Chinese or even Old Chinese. There are certainly systematic changes going on, although nothing is ever perfectly consistent when it comes to organically evolving languages.

Regarding your second point, I do indeed find it strange that you’ve avoided noticing 月/肉 for so long! This is much clearer in traditional Chinese where 肉 is more often (but not always) written differently (I wrote about this and related issues here). A similar problem is 玉, which is written as 王 when it appears on the right, both in simplified and traditional.

We have to realise, though, that the purpose of dictionaries is normally not to help us analyse characters, but to sort characters and words into an order that makes them easy to find. If people see 王, but you sort it under 玉, it makes it harder to find if you don’t know that 王 is actually 玉. I don’t know if this is the actual reason, but it does make sense to me. As a learners, knowing about the origin can sometimes be extremely useful (as in your case with moon and meat), but sometimes not. What’s the top part of 看? Well, you’d think it’s a variant of 手, right, and that it’s hand shading an eye, so a semantic component? Nope, according to Outlier, it was originally a phonetic component that looked nothing like 手, but more like 倝.

I haven’t worked with dictionaries, but I’ve spent a lot of time with characters with the Skritter team, and such questions are very tricky. For me, it’s obvious that you should say that 月 in 脸 actually means “meat”, which makes it much easier to make sense of lots of characters with that component. But does it make sense to analyse 看 as 倝 (a character almost no student will ever see) plus 目 and call it a phono-semantic compound, or do you go with the superficial form or folk etymology version that it’s a hand shading an eye? These are two extremes and pretty easy to deal with, but where do you draw the line? How do you draw it? This gets really complicated really fast, especially if your goal is to be pedagogical instead of just being correct. 🙂

Very long response here, but I hope you found at least something interesting in it!

Thanks for your reply – it’s definitely a tricky issue. I suppose in practice it comes down to whether learning the rule saves you time or improves accuracy in the long run, but it’s hard to know and of course people are different. It reminds be of how the top performers in spelling bees memorise the spelling rules of Greek, Latin, French etc and can then spell words they’ve never heard before, but that doesn’t mean it’s worthwhile for the average person to learn that way. It’d be nice if there was a more systematic resource for this find of knowledge. For example I’d love it if dictionaries indicated whether a word’s meaning was obvious, related, or unrelated to its constituent characters, though that would be obvious be very time-consuming to create.

You’re right that I’m learning simplified characters (I live in mainland China before the pandemic) but I also probably could have stood to spent more time on components early on as you suggest on this site. I’ve started to learn traditional characters but it’s not a really priority just yet so I haven’t gone beyond the most common. I think another reason is that I’ve heavily prioritised reading over writing, which I still think is the right decision (I lived in China for two years and only very rarely would writing have been helpful) but I wonder if you have any thoughts how that changes the ways that people learn the characters – you’d still want to be familiar with the components etc for reading of course, but I assume it probably would change the optimal approach somewhat.

I’ve found it most help to focus on links between characters and words – in my Anki deck each vocab card lists, for each character in the word, any other words in the deck that include that character. I’ve found that very helpful to get a better intuitive understanding of the semantic meaning of the character and to identify when it’s just being used for its phonetics and just for general help with remembering. I do also include a breakdown of the character by components which is also often helpful for characters like 想 for the reason you mention in the article, but that actually started off as a bit of a crutch because I didn’t know the components as well as I should have.

To your last paragraph, it is indeed not complete. When is part 5 coming out?

I originally intended to publish it tomorrow, but it’s taking much longer to edit than I thought, so probably the week after that! The fact that you asked about it adds a little bit of energy that I can use to get it done. 🙂

Awesome! These last 2 days I’ve been reading lots of your posts before starting learning Chinese so I can have a smart strategy to learn it efficiently, and it helps a lot! 🙂

There, the article is now published! It took an awful lot of time to write and I’m not even happy with the result, but hopefully, someone might get something out of it. If not, you can wait for next week’s article which will be a bit more practical. This week’s article is here: The building blocks of Chinese, part 5: Making sense of Chinese words

Hi Olle,

I love your site and podcast. I am a long-time beginner struggling to make the jump to intermediate.

One issue I have is that I use Skitter for learning and writing characters, but I don’t find it very helpful for words of two or more characters, especially those with different meanings in different parts of speech or different contexts. Do you have a recommendation for how to split out that part of learning?

Could you provide a few examples and elaborate a bit on why you don’t find it helpful? I think I can guess, but all words have different meanings in different contexts, and clearly the same word being used as a verb will not have the same meaning as when it’s a noun, and this is also very common in Chinese. My general answer to this is that you should use flashcards to learn the basic definition, meaning, pronunciation and so on, but that beyond that, you should much, much more reading and listening than you do flashcards. Then you will see these words being used in context. If you’re struggling with a particular usage that seems completely different from the basic meaning (this does happen), you can study sentences instead. You can do this in Skritter, too, although it’s a little bit awkward because cloze deletion isn’t really built into the app.