Learning to pronounce Mandarin Chinese properly comes with a number of challenges. Some of these are relevant for learning any foreign language, some are particular to Mandarin in particular.

Learning to pronounce Mandarin Chinese properly comes with a number of challenges. Some of these are relevant for learning any foreign language, some are particular to Mandarin in particular.

In general, we need to learn two things:

- First, we need to learn how to pronounce and distinguish sounds that don’t exist in our own language or adjust sounds that do exist in our language, but are pronounced somewhat different. We also need to master pronunciation beyond individual sounds, including tones and intonation. With practise and a good teacher, all students can overcome these challenges.

- Second, we need to learn how the sounds are written down. Learning how sounds are written enables us to use dictionaries, learn the pronunciation of new characters and words, and in general access the sounds via the written language. It’s also more or less a requirement in modern society, because most Chinese input methods on computers and phones are based on typing the sounds rather than the characters.

Pronunciation written down on paper is not the same thing as the sounds themselves, yet they are often mixed up, leading to inefficient learning and teaching, something I wrote about in an earlier article you can check out here: What’s the difference between Chinese pronunciation and Pinyin? Does it matter?

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to this article:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many more!

The currently dominating romanisation system (a system used to convert written text to our alphabet from another script) is called Hànyǔ Pīnyīn (汉语拼音), or just Pinyin for short. There are other systems in use as well, but in this article, I want to focus on Pinyin, as that is what a vast majority of students learn first. My goal is to help you achieve the second goal described above by highlighting and explaining some of the traps and pitfalls that await students learning Pinyin.

If you don’t want to read my preamble and notes for beginners, click here to scroll directly to the overview of Pinyin traps and pitfalls.

Learning Mandarin pronunciation as a beginner

Before I start going into details, I want to say a few words about learning to pronounce Chinese as a beginner. Learning proper pronunciation is a matter of taking responsibility. If you’ve just started learning Chinese, your teacher will probably help you a lot, but the likelihood is that you won’t receive much help once you’ve learnt the basics.

It’s important to realise that if your teacher or other people around you don’t correct your pronunciation, this is most likely not because your pronunciation is perfect. Indeed, Likewise, if native speakers praise your Chinese, be happy, but don’t use it as an assessment of your actual ability. Getting honest feedback is actually much more difficult than it should be. You can get implicit feedback by observing how people react to what you say, but to get explicit feedback where someone directly tells you what you’re doing wrong and does so accurately is not common. I wrote more about this here: How to get honest feedback to boost your Chinese speaking and writing.

In fact, your teacher should have already told you what I’m going to bring up in this article, but since I know that many teachers don’t do that and that many students still make these mistakes, I think these problems are worth highlighting. Also, some students learn on their own without a teacher.

The most important lesson of all is that Pinyin is not English. You should never guess how something is pronounced based on your understanding of English spelling (or German spelling or Spanish spelling). There are only around 60 initials and finals in Mandarin, so you can learn all of them by listening carefully and mimicking. The written word should be an aid to memory, not a guide to how the syllables are pronounced!

Poor understanding of Pinyin doesn’t mean that Pinyin is bad

Please note that these problems usually arise because of a poor understanding of Pinyin. This might be because your teacher didn’t explain it well enough or because the textbook is bad, but it could also be that the student didn’t pay attention, was overwhelmed with other things at the time or simply forgot. For the purpose of this article, it doesn’t really matter which, as the outcome is the same: an incomplete understanding of Pinyin and, as a result of that, poor pronunciation (see Bassetti, 2007, for some empirical data related to this).

Something should also be said about dialects. Mandarin is spoken by hundreds of millions of people over a vast area. Naturally, there is much variation. I’m not writing this article to say that all other variants of Mandarin are useless or bad in any way. Still, I think most people should and want to learn standard pronunciation to start with, even if I encourage people to experiment with accented Mandarin or other Chinese dialects later on.

The Hacking Chinese guide to Pinyin traps and pitfalls

This guide is separated into several areas, and you can click on each to scroll directly to it. Click “back to overview” to scroll back up again, or hit the back button in your browser.

The list of issues below isn’t exhaustive, because I’ve tried to include problems that learners are least likely to be aware of. Thus, this is not an introduction to Pinyin and Mandarin pronunciation in general, but a close look at specific cases where students often make mistakes. If you want a complete guide to Mandarin pronunciation, you can check out my course Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence, which is comprehensive and teaches you everything you need, starting from nothing.

Overview of Pinyin traps and pitfalls

- Vowel omissions and abbreviations

- Vowel overlap (one vowel, many sounds)

- -in/-ing, -an/-ang, -en/-eng

- Aspirated and non-aspirated consonants and glides

- Why is Pinyin so confusing?

I have included sound samples for each problem I discuss, all taken from my course. The voice belong to a native teacher from Beijing. If you want to be able to browse and listen to all syllables in Mandarin, you can check out AllSet Learning’s Pinyin chart here. I’ve used the same IPA symbols as I do in my course, which means it mainly follows Duanmu (The phonology of standard Chinese, 2007) and/or Lin (The Sounds of Chinese, 2007).

1. Vowel omission and abbreviations

Many syllables in Pinyin are abbreviated. If you don’t know this, you will make mistakes!

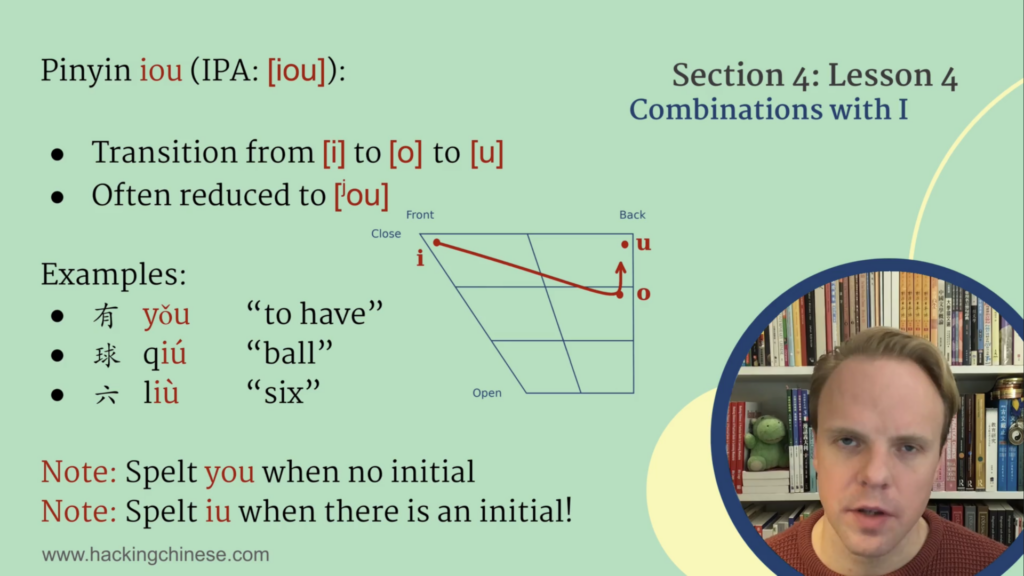

1.1 Spelt –iu, pronounced –iou

The syllables diu, liu, niu, etc., are pronounced -iou and should rhyme with 有 (yǒu) “to have”, for example. The syllables you and liu using IPA phonetic symbols are written as [iou] and [liou] respectively. Note that the “i” is usually pronounced as a glide (noted with a superscript “j” in IPA), but the point here is that these syllables rhyme.

The syllables diu, liu, niu, etc., are pronounced -iou and should rhyme with 有 (yǒu) “to have”, for example. The syllables you and liu using IPA phonetic symbols are written as [iou] and [liou] respectively. Note that the “i” is usually pronounced as a glide (noted with a superscript “j” in IPA), but the point here is that these syllables rhyme.

Just don’t forget the omitted vowel o and you’ll be fine!

To learn more about this, check number 5 here or lesson 4-4 in the pronunciation course.

1.2 Spelt –ui, pronounced –uei

Syllables ending with -ui, such as dui, tui, shui, sui, etc., are actually pronounced as if ending with -uei, which would be [wəi] IPA. Thus, dui should be pronounced [twei], sharing the last two sounds with syllables such as bei, fei, dei, etc. Here’s how the syllables dui and mei are written with phonetic symbols: [twei] and [mei].

Don’t forget the omitted vowel e!

Listen: duì, shuǐ

…and compare: bèi, fēi

Learn more about this in lesson 4-3 in the pronunciation course.

1.3 Spelt –un, pronounced –uen

Syllables such as lun, dun, shun, gun and so on, are all pronounced almost as diphthongs (double vowel sounds). Using IPA, sun would thus be written [swən], but it might help to think of this as su + en. In other words, the final sound is -en, even if there is no “e” in the actual spelling of the word. You don’t need to overdo this, but it’s pretty easy to hear once you know what to listen for. If you find it difficult to hear, syllables with third tones are usually easier to hear, so check gǔn below.

Don’t forget the omitted vowel e, but don’t stress it too much either!

Learn more about this in lesson 4-3 in the pronunciation course.

1.4 Spelt –o, pronounced as –uo

The syllables bo, po, mo, fo are actually pronounced buo, puo, muo, fuo, which means that they rhyme with duo, tuo, nuo, luo and so on. Using IPA, this sound is written [wo]. For example, bo and duo are written as [pwo] and [two] respectively. As we can see, these syllables rhyme. Because the spelling is different in Pinyin, some native speakers will insist that they are different, but it’s easy to show that bo, po, mo, fo are not pronounced with the same final as, for example, lo. You can also say that the lip rounding comes from the preceding consonant, which is fine, but the end result is still that it rhymes with duo, tuo, nuo, etc..

Listen: bō, mò

…and compare: duō, ruò

For a more detailed discussion of this, check number 4 here or lesson 4-4 in the pronunciation course.

2. Vowel overlap (one vowel, many sounds)

Unlike the International Phonetic Alphabet, Pinyin was never designed to have a one-to-one mapping between sounds and written symbols. In this regard, Pinyin is similar to other languages, although the spelling is of course much less chaotic than in English. Here are some important examples where one letter is used to represent many different sounds:

2.1 The letter “e” represents four different sounds

- First, when it’s the only vowel, it is a close-mid back vowel [ɤ]. This is the sound in 饿 (è) “hungry” or 哥 (gē) “older brother”, for example. This is often realised as a diphthong [ɯɤ] (those are both unrounded back vowels). Note that how clear the two sounds are depends on the syllable, too. If you compare è and gē below, you’ll hear it more clearly on è than gē.

Listen: è, gē

Learn more about this in lesson 4-5 in the pronunciation course. - Second, before the nasals -n and -ng, it becomes central vowel [ə], for example in 冷 (cold). A short version of this is pretty close to the sound used when the syllable is reduced, which is the case in common particles like 的 and 了, but also in words like 觉得 (juéde) “to feel; to think”, and 什么 (shénme) “what?”.

Listen: lěng, gēng, juéde, shénme

Learn more about this in lesson 4-5 in the pronunciation course. - Third, following an i, such as in lie, bie or xie, it becomes a close-mid front vowel [e] instead. This is the sound you’re asking about, e.g. 也 (yě) “also”. Note that the final -ie is spelt ye when there’s no initial, but the pronunciation remains the same.

Listen: yě, bié

Learn more about this in lesson 4-4 in the pronunciation course. - Fourth, the “e” in e.g. mei and mie are slightly different sounds, with the first using [e] as we have already discussed, and the second using [ɛ], which is more open (tongue drops a bit). This difference is not crucial for communicative purposes, but should be clearly audible in the below examples if you listen carefully:

Listen: bié, xiě

…and compare: bèi, fēi

2.2 The letter “a” represents three different sounds

- First, as an open central vowel [a], in these combinations: ia, ai, an.

Listen: jiā, ài, ān

Learn more about this in lesson 4-2 and 4-4 in the pronunciation course. - Second, if followed by -ng or -o, it’s pronounced as a back open vowel [ɑ], such as in -ang, -ao, -iao, -iang.

Listen: máng, niǎo

Learn more about this in lesson 4-2 and 4-4 in the pronunciation course. - Third, it can also be pronounced as close-mid front vowel, [æ] (or [ɛ]) in -ian (including yan) and -üan. This is not the same sound as in -an and -uan!

Listen: tiān, juān

…and compare: ān, duǎn

Learn more about this in lesson 4-4 and 4-6 in the pronunciation course.

2.3 The letter “i” represents four different sounds

- First, it’s a front closed vowel [i] and occurs in: ni, bi, xi etc..

Listen: nǐ, xī,

Learn more about this in lesson 4-4 in the pronunciation course. - Second, it can be pronounced further back and slightly more open [ɪ] in -ai and wai.

Listen: wài

Learn more about this in lesson 4-2 in the pronunciation course. - Third, i represents the empty rhyme following z, c and s. This sound can be described in many ways, but it’s fairly close to English [z], but with slightly more air allowed to pass through. It’s a type of vowel that uses the tongue tip, something we don’t see in English, which is why it almost feels like a consonant.

Listen: cì

Learn more about this in lesson 4-7 in the pronunciation course. - Fourth, it also represents the sound following zh, ch, sh and r. This is the same as the previous sound, but pronounced in the retroflex position (i.e., the tongue is retracted and raised as when producing the zh, ch, sh and r sounds; the tongue doesn’t move much). This sound is also fairly close to a thick, retroflex r, so it’s possible to think of these sounds as zhr, chr and shr Be careful not to drop your tongue too much, because then shi might sound more like she.

Listen: chī

…and compare: chē

Learn more about this in lesson 4-7 in the pronunciation course.

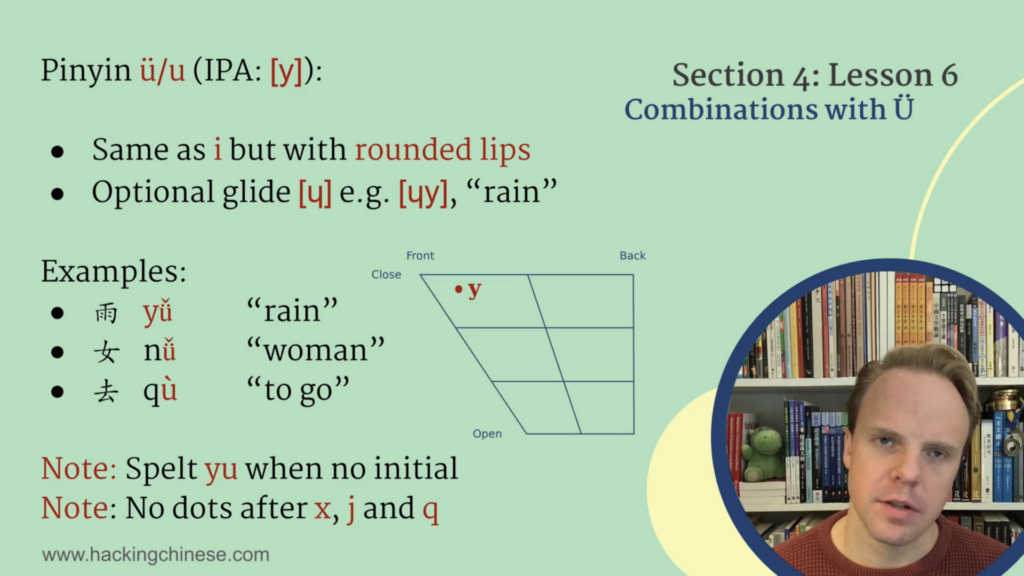

2.4 The letter “u” represents two different sounds

First, it’s a back closed vowel [u] and occurs in: bu, shu, lu etc..

First, it’s a back closed vowel [u] and occurs in: bu, shu, lu etc..

Listen: lù, shù, nǔ

Learn more about this in lesson 4-3 in the pronunciation course.- Second, it can be a front closed rounded vowel [y] after j/q/x/y. This sound is otherwise spelt with two dots: ü, but these are only written when there is ambiguity, so for example in 女 (nǚ) “woman”, compared to 努 (nǔ) “to exert (effort)”. This is one of the most common problems when students don’t learn Pinyin properly. Make sure that you learn to pronounce [y] and that you know when a u is actually ü (after j/q/x/y).

Listen: nǚ, qù

…and compare: nǚ, nǔ

Learn more about this in lesson 4-2 in the pronunciation course.

3. -in/-ing, -an/-ang, -en/-eng

These pairs cause problems, because many students look at the spelling and see the same letter and therefore conclude that the vowel sound in -in is identical to the vowel sound in -ing. This is not the case. In standard pronunciation, the quality of the vowel sound is different in e.g. yin and ying. The first only contains a single vowel sound, whereas the second is a combination of i and -eng and is almost pronounced as a diphthong. Exactly how it’s pronounced depends on the speaker as well as what syllable it is and what tone that syllable has.

Listen and compare: yin [in] and ying [jəŋ].

In the case of -an/-ang and -en/-eng, the vowel sound in the second syllable in each pair is pronounced further back, which is not too hard to hear if you listen carefully.

Actually, the way -n and -ng are pronounced causes some problems, because it’s not entirely the same as in English. The -n is close enough, but the -ng is pronounced much farther back in Chinese than in English, making the difference between the sounds bigger. However, note that depending on region, many native speakers can’t distinguish these two phonemes and pronounce both as -n.

Listen and compare: dan, dang and gen, geng.

4. Aspirated and non-aspirated consonants

Aspiration is usually the first thing I focus on when teaching Mandarin pronunciation. It can be described as a puff of air following the consonant, similar to what you get after the initial “p” in English “put”, but stronger. There is a whole range of sounds in Mandarin that are mainly distinguished based on aspiration, but many learners ignore this and rely on voicing instead. This is a good example of when reading Pinyin as if it were English is not a good idea.

Why learning Chinese pronunciation by using English words is a really bad idea

The difference between the following consonants in Mandarin is aspiration, which is usually written as superscript h with phonetic symbols. This is different from English, where voicing is part of the difference. In Mandarin, the first consonant is not aspirated, the second is aspirated:

- b/p

- d/t

- g/k

- j/q

- zh/ch

- z/c

Note that none of these consonants are normally voiced! If you put your fingers to your throat, you should not feel the vocal cords vibrating as when you say [z] in English. Instead, the difference is that the latter in each pair has a strong puff of air and the first does not. Thus b/p in Mandarin are transcribed as [p] and [pʰ] respectively, d/t is [t] and [tʰ], and so on.

In fact, no consonants or glides in Mandarin are voiced, except these: m, n, ng, l, r

Also note that voicing of these sounds is not straightforward in English either, see this article for more details.

5. Why so many inconsistencies?

After a while, most students ask themselves this question. Why all the irregularities? It’s easy to explain why English spelling is irregular (it wasn’t designed, it has evolved for over a thousand years), but Pinyin is a relatively modern invention. I’m not going to go into details here, but I just want to point out that there are explanations for most oddities, which means that they aren’t really oddities at all.

The key insight is that Pinyin was not designed with foreign learners in mind. Therefore, most things that are difficult for us are actually obvious if you speak Mandarin fluently when you start learning Pinyin, which native children do, but almost no adults do.

Let’s look at a few common gripes students have with Pinyin and why they actually make sense:

- Why is ü sometimes written u? It’s only written u when there is no ambiguity. For instance, xü is redundant, since there is no xu sound in Mandarin. Thus, using u for words where there is only one sounds saves some diacritics and is easier to use once you’ve learnt it. Considering that Pinyin wasn’t designed with foreign students in mind, this becomes a lot more logical.

- Why does the spelling of u, i and ü change at the beginning of words? Let’s use a common example, the word wenyan, which is pronounced uenian. However, as you can see, the second spelling is a bit awkward, because it can be parsed in many different ways (u-en-ian, uen-i-an, etc.), wenyan on the other hand can only be wen-yan because w and y can only occur as initials and there is no risk for misunderstanding. Reading is also faster when segmentation into syllables is easier. Furthermore, have you ever typed the name of the city 西安? In most input systems, you will get the syllable xian (such as in 先), and need to add an apostrophe and type xi’an. If we didn’t have w, y and yu at the beginning of words, this would happen much, much more often.

- Why all the confusion with one vowel, many sounds? This is because the Chinese syllable is typically broken down into three parts: initial, medial and final. Thus, you shouldn’t think of each letter as being a separate unit, but rather being a part of one of either the initial, medial or final. If we look at a, we should regard -an, -ang and -ian as three different units. Sure, they all contain the letter a but you should learn the pronunciation of these units, not of the individual letters. Also, don’t forget that the spoken language comes first, so the question isn’t really why a can be pronounced in many different ways, but rather why a is used to write many different sounds. It’s convenient, of course! Since these different sounds aren’t used to distinguish different words in Mandarin, using a single letter is fine.

Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence

My hope is that you have found this article helpful and I have provided audio recordings and explanations to make sure that you don’t actually need more to avoid these traps and pitfalls. If you want to know more, however, and want a complete guide to everything I’ve mentioned here and much more, please check out my pronunciation course. It’s not always open for registration, but if it’s not open when you check it out, you’ll be able to leave your email address so I can contact you when it comes available again.

Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence

References and further reading

Bassetti, Benedetta (2007) Effects of hanyu pinyin on pronunciation in learners of Chinese as a foreign language. In: Guder, A. and Jiang, X. and Wan, Y. (eds.) The Cognition, Learning and Teaching of Chinese Characters. Beijing, China: Beijing Language and Culture University Press. Available here.

68 comments

1. I also read the book. 🙂 It’s mostly accurate; however, there are a few errors. 還是一本好書,「瑕不掩瑜」啦。

2. The reason why bo, po, mo, fo are not written as buo, puo, muo, fuo is the degree of rounding is not so much as the true -uo syllables. Note that b-, p-, m-, f- are already lip sounds. If we did write buo, puo, muo, fuo, the [w] would sound too strong. In Mandarin Phonetic Symbols, the weak [w] is also missing in the written form. i.e. 用注音寫也是ㄅㄛ、ㄆㄛ、ㄇㄛ、ㄈㄛ,而非ㄅㄨㄛ、ㄆㄨㄛ、ㄇㄨㄛ、ㄈㄨㄛ。

3. In fact, no consonants or glides in Mandarin are voiced, except these:

m-, n, -ng, l-

Plus r- ← But people tend to pronounce it like an approximant, so the voicing is weaker and the following empty rhyme or final is more obvious.

And I wonder whether the -r in er-suffixation also counts (consonant overlap: one r with many sounds).

Hi,

I fixed the spelling mistake you pointed out in your comment, no worries. 🙂 Regarding the pronunciation of -uo, the difference is reflected in both Hanyu Pinyin and Bopomofo (compare bo, tuo, etc.). However, even though there might be a slight difference, I think it should be pointed out that these sounds are much, much closer than some other sounds that are given the same spelling. Also, I think it’s hard to say what is the “correct” way of transcribing this sound. Duanmu uses the same phonetic symbols and he’s not alone. The fact that it’s different from Bopomofo doesn’t mean it’s wrong.

Thanks for pointing out r- and -er, I just plain forgot about them. As you say, there are a number of different ways both of pronouncing and transcribing r-, but should still be mentioned. I think 兒化 should also count, although I don’t consider that crucial in this case. I have added r- to the article, thank you!

About Duanmu’s book, the errors I mentioned have nothing to do with the symbols actually. :p Those are fine. It’s about overgeneralizing partial facts. I remember there’s section on Taiwanese accent in that book. It’s a useful reference and worth reading, but I think the samples the author collected were not sufficient enough to represent all the traits in Taiwan. It has been a long time since I read the book. I need to confirm it.

I’ve learned a lot from your article, informative and clear. Thanks~

Ah, I see. I don’t remember the section on Taiwanese Mandarin very well, but I think overgeneralisation is a quite common error not only in this case, but in most research, especially in secondary sources. Still, I think the book is one of the most interesting one’s I’ve read about languages. It covers a vast area of linguistics and yet manages to be readable and comprehensive. Basically, it’s the book that made me realise that linguistics can be quite fun. 🙂

Oh, my God. It should be “a section.” Another negative transfer from Chinese, ha.

Hey!

Thanks for the discussion on Twitter. I finally managed to make it home and track down some of my old textbooks.

According to Ladefoged’s contribution to the Handbook of the International Phonetic Association, under the conventions section for American English, the consonants [b d g] “have little or no voicing during the stop closure, except when between voiced sounds”. Though my scrawled margin notes show that my lecturer seemed much more insistent that we transcribe using [p t k] instead of [b d g] than the handbook suggests.

Seems to be more a case of allophonic variation, so I’d like to retract my original, more definitive, statement on the subject on Twitter.

Thanks for challenging me on it, as it’s helped my understanding further.

And, again, a great article!

It is I who should thank you for the challenge! I wrote that paragraph without thinking too much and only realised that there might be a possible problem once you raised it. I think challenging and being challenged in a reasonably friendly way is an excellent way to learn, which is partly why I like publishing articles like this and discussing them with people.

Regarding these stops, as I said on Twitter, there is a significant difference between English and Chinese, but it’s not as clear cut as I made it look. As you point out, these stops are often voiceless in English too and there is aspiration as well, although perhaps most native speakers don’t realise it (compare p in spin and pin). So, thanks again for highlighting this!

such a useful article!

however the “Listen” links return an error, “this page cannot be loaded via the proxy”

This is probably an error at your end, the audio works perfectly here and the sound files are available on the server as intended. Based on the error message, something’s wrong with your proxy, but based only on that error message, I have no idea what. You probably know more about thees things than I do anyway! You could try right clicking and saving the audio instead? In any case, the links work fine for me.

yup, sorry about that, I only get that message on my Android phone … using Chrome Beta. Works ok on other Android browsers, on a PC, and on iPad.

While I am here, I can ask you a perhaps more interesting question 🙂

I have always learned using pinyin, but being in Taiwan, I’ve often thought I should learn zhuyin/bopomofo. I imagine it is less wrong, or at least differently wrong, as a system of phonetic representation. So should I learn zhuyin? And which phonetic system do you like best? 🙂

(I recently asked a Chinese teacher which is faster/easier to write for her (on the board), pinyin or zhuyin. She said pinyin because you can write it all in a line.)

I think Pinyin is more practical to use and I type relatively quickly with Dvorak + Pinyin input, switching to Zhuyin would seriously decrease typing speed for a long time. I also find it easier to write by hand, although that’s mostly because I haven’t used Zhuyin in a while and wouldn’t be a big problem if I decided to start using it. From a pronunciation perspective, I think it’s worth learning Zhuyin simply because you’re not as constrained by orthography. This benefit is two-fold. First, you are less likely to suffer transfer from your native language, but instead forced to just listen. This can of course be done with Pinyin is well, it’s just that you have no choice with Zhuyin. Second, there are studies that show that orthography does influence both production and perception of a foreign language. Thus, it might be the case that it’s actually harder to hear/pronounce sounds that are not present in the written system (there are many examples in this article). As you can see, this topic is complicated enough to merit an article of its own, which is indeed in the pipeline!

Zhuyin indeed doesn’t suffer from the problem of transfer, though I agree that pinyin is much better for typing, since it’s actually trying to map against the English letters on the keyboard.

On the other hand, pinyin is too dominating for foreigner’s good. Foreigners should treat pinyin like romanji.

Zhuyin solves most of the problems with Pinyin mentioned in the article. As far as typing, it would decrease speed at first, but later it would increase, because the key strokes are fewer. I had never heard of Dvorak, but it would be the same situation, i.e. typing speed would significantly decrease while learning Dvorak, but afterward would be faster than QWERTY. I know Zhuyin and Pinyin, but I still use Pinyin for typing, for the same reason I won’t learn Dvorak. I don’t want to take the time to get accustomed to it.

Isn’t that more or less exactly what I said in the comment you replied to? 🙂 In general, I think that practical aspects (typing) need to be separated from linguistic aspects (listening and speaking). I highly doubt that it matters for intermediate or advanced learners which transcription you use when typing, but it reasonable to assume that which system you use when first learning to hear and pronounce the sounds of the language does matter. So, in essence, for serious learners, the fact that Zhuyin is harder to type shouldn’t matter, although it certainly does for the average learner. Being able to approximate sounds faster as a beginner is really only a benefit if you’re a tourist, and that’s not the target group of anything I write here. I have written more about Pinyin, Zhuyin and IPA in an article series starting here, but in general I agree that Zhuyin would be better for initial contact with the sounds for the reasons mentioned in my comment above.

Regarding the pronunciation of b/p, actually Chinese and English are similar in that the feature that differentiates them is predominantly aspiration, not voicing. English does have sort-of voiced consonants, but there’s a voice-onset lag (the voiced part comes slightly after the articulation)so they’re arguably not truly voiced.

What this means is it’s not really worth fretting about ‘b’ in Chinese if you’re a native English speaker. P is more or less ok, but in Chinese the aspiration is stronger. For an English speaker, that’s a very easy minor adjustment.

If you’re learning a language like French or Russian which have truly voiced consonants, people can have difficulties understanding you if you don’t work on differentiating voiced/unvoiced consonants, but in Chinese it’s a very minor difference.

Yes, I agree with at least the first part. However, I don’t think that mastering voicing in Chinese is necessarily an easy task for English speakers. Sometimes adjusting existing categories is much harder than creating entirely new ones, at least if we look at a slightly longer time period (it’s of course easier to approximate similar sounds, but it might be hard to move beyond this early approximation). Having taught a number of people with English as their first language, I don’t think that aspirated initials in Chinese are easily mastered, but I do agree that the unvoiced, unaspirated initials typically aren’t a problem since they can be understood even if pronounced as they are in English.

Man that`s fantastic, why don`t you compile all that information spread to your posts (and the other useful things you know from other sites and books as well) in one simple guide in text/pdf? As a recent learner I fell that the biggest problem is that all that information is spread between so many real and virtual pages that ones can`t get it without wasting hours reading unrelated things or thing he already knows, add to that the differences and contractions between different authors and the problem becomes even bigger.

The ideal guide would contain almost everything you need to know about grammar and pronounce without spending too much time discussing about simple and conceptual stuff but without hiding all the details that courses and teachers won`t tell you.

I am in fact working on just such a guide, which is meant to be something like a Hacking Chinese 101 that goes through everything you really need to know without focusing too much on in-depth discussions and detailed descriptions. The problem I face when writing anything like this is that if I could somehow magically transform what I want to write into a book, it would be ten thousand pages long, so I need to figure out what to focus on and how to limit the scope. This isn’t easy!

Olle,

Great article. My wife (他是台灣人)tells me that the Bo po mo and fo are pronounced more as they appear and not as buo puo, etc. She says mainland Chinese mislearn via pinyin, and when they speak 中文 they have an accent. Pretty funny — the Taiwan vs mainland differences in perception run deep. The sounds you provide are helpful. 我的老婆和她的媽媽都說 that I should learn bo po mo fo to learn pronunciation. Looks like that is my next step

I have to disagree with the bo/po/mo/fo pronunciation. It’s pretty much standard to transcribe these finals the same way as those ending with -uo when doing phonetic transcription. The reason many native speakers feel that this isn’t right is that 1) it’s not spelt like that (which matters) and 2) there is a lip-rounding element in the initial already, which makes the “u” part less distinct. It’s still there, though.

No. The lip rounding comes from the consonant, not the vowel. You are trying to map the sound back into English, that’s why you are hearing it.

Mandarins are not stickers about pronunciations the way English is, because it’s not a phonetic language. All the “implicit” sounds you hear are unimportant to Chinese, and trying to distinguish the way you do is what makes learning complicated.

Yes, the lip rounding comes from the consonant, but influences the following vowel in such a way that many linguists transcribe the vowel sound in e.g. bo and duo the same way. I’m not basing this on what I hear. I think treating similar sounds the same way makes learning easier.

Any linguists transcribing as such would be wrong, as these sounds are different to Chinese’s ears, and combining them is forcing a foreign view onto Chinese.

It would be like Chinese telling French that /d/ and /t/ are similar sounds because they are indistinguishable to Chinese’s ears, so therefore should be treated the same.

This is a very offensive comment. Your wife a strong bias against mainland Chinese. The standard pronunciation for Putonghua and Guoyu is based on Beijing. Saying that mainland Chinese people have an accent while speaking 中文 is even more ridiculous. Firstly, you are confusing 中文 with a fixed pronunciation in general. Secondly, you claim that people from Taiwan don’t have an accent. In fact, the way Taiwanese people speak is artificial because they imitate a form of speech that is not native to the island. A final point is the extreme political stance on simplified characters, which contradicts with the daily use of 台灣 instead of 臺灣.

Shouldn’t “dui”, “tui” and “shui” be pronounced “duei”, “tuei” and “shuei” and not as they’re written? Because I think one of the sound files is a mistake.

Overall, I think this guide is helpful.

I just listened to the sound file and I think it sounds perfectly normal (according to the description in the article)! Just to make sure we’re talking about the same thing, I’m referring to the sound file with dui, tui and shui.

Thanks, Olle. I must’ve misheard that sound file. Also, it was 7 in the morning where I live when I first listened to it xD

It is slightly tangential to this discussion, but Hanyu pinyin is not only confusing in its own right but also tends to be reinterpreted according to the wide range in variation of Indoeuropean language backgrounds. In particular, I am very aware that the vowel quality implied (but not explicitly indicated) is often assumed by some English speakers but is entirely foreign to others like myself. (Just listen to someone from central Scotland pronouncing “way” or “now” and compare it to the same from Northern Ireland or the south of England – worlds apart!) It becomes a moot point whether the vagaries of a script that is never actually used in practice, i.e. pinyin, is worth bothering to learn. The detailed description of its quirks above certainly seems to suggest that it isn’t.

Let’s be technical. What’s the 4th way of prounouncing e?

It is mentioned in the article already:

That gives us four readings: [e], [ɛ], [ɤ] and [ə].

I don’t know if there’s a variation or something but that’s very different from the way was taught, specifically:

liu is [ljou] not [ljəu]

leng is [lɤŋ] not [ləŋ]

-ang, -ao, -iao, -iang are [a] only uang uses [ɑ] (the ng do make the frontal vowels go back but not like that audio, they go to the middle of the voice at best looking more like [ɐ])

yan/üan use [œ] not [æ]/[ɛ]

there no such thing as a [ɪ] sound

si zi ci are pronounced with [ɯ]

Now there’re 4 rational explanations for that:

1-The gods of phonetics are testing my faith.

Probably true, but also:

2-They pronounce those sounds halfway in, so nobody knows what symbol to use.

I doubt that, they all seem very different to me.

3-There’s no such thing as a (specific) standard vowel position for mandarin, so everybody draws conclusions based on different accents.

Probably the case here. Btw the guy who taught me spoke taiwanese mandarin (he was suppose to use a standard transcription, but how standard is his standards if there’s no standards in the first place?)

I also consulted a third source, and surprisingly enough, it was different from both what I learned and this post.

There will always be different choices for narrow transcription in any language, partly because phoneticians have different opinions of how to best describe a sound and partly because people pronounce sounds differently, meaning that they will describe different sounds. I’ll comment on your observations one by one:

It took a while to convince me that the second is more accurate. It’s very seldom the case that people pronounce a full [o] in this syllable and it’s more like the tongue passes [ə] on its way to [u]. If you combine [o] and [u] after [i/j], it does not sound natural and is very hard to say.

It’s definitely not [ɤ]. That sound is very far back and no-one I’ve heard pronounces the “e” in 冷 as the “e” in 餓. Of course, if you have defined [ɤ] in some other way, you might get away with it, but I think [ə] is much more accurate.

There is individual variation here, but the audio is recorded by a native speaker born and raised in Beijing who has passed all the relevant pronunciation tests. It’s pretty standard to write any “a” preceeding “-ng” as [ɑ]. I have read MANY books about Chinese phonetics and I have never seen [ɐ]. I think it’s more debatable what to use for “-iao” and “-ao”, but the point here is that they are farther back than the normal “a”. I think the problem might be that this isn’t truly narrow transcription, people just make a difference between front and back “a” and don’t care about the details. This is surely enough for students, though.

In the first case, this is certainly wrong. [œ] is rounded, and the sound in “yan” is definitely not rounded. I suppose you could claim the lip rounding of “ü” influences the following vowel, but I still find it very strange to use a rounded vowel to represent this sound.

This is a matter of taste, I think. You can argue (as I have done) that the “i” in these syllables are slightly further back and more open than [i]. Very few people pronounce “lai” with a cardinal [i]. Still, I wouldn’t consider writing [i] instead wrong, just slightly less accurate.

This is fairly common and the normal way of doing it in modern IPA. The reason I didn’t write this in the article is that almost no students have seen [ɯ] before. It also fails to properly account for the fact that the “i” in these sounds is an apical vowel and not exactly identical to [ɯ] in the IPA chart. In other words, you need to also raise the tongue tip to produce a proper zi, ci, si. If you combine the cardinal [ɯ] with the initial, you won’t end up with good zi, ci, si. Still, I think [ɯ] is the best way of writing this sound!

I hope this makes things clearer!

There will always be different choices for narrow transcription in any language, partly because phoneticians have different opinions of how to best describe a sound and partly because people pronounce sounds differently, meaning that they will describe different sounds. I’ll comment on your observations one by one:

It took a while to convince me that the second is more accurate. It’s very seldom the case that people pronounce a full [o] in this syllable and it’s more like the tongue passes [ə] on its way to [u]. If you combine [o] and [u] after [i/j], it does not sound natural and is very hard to say.

It’s definitely not [ɤ]. That sound is very far back and no-one I’ve heard pronounces the “e” in 冷 as the “e” in 餓. Of course, if you have defined [ɤ] in some other way, you might get away with it, but I think [ə] is much more accurate.

There is individual variation here, but the audio is recorded by a native speaker born and raised in Beijing who has passed all the relevant pronunciation tests. It’s pretty standard to write any “a” preceeding “-ng” as [ɑ]. I have read MANY books about Chinese phonetics and I have never seen [ɐ]. I think it’s more debatable what to use for “-iao” and “-ao”, but the point here is that they are farther back than the normal “a”. I think the problem might be that this isn’t truly narrow transcription, people just make a difference between front and back “a” and don’t care about the details. This is surely enough for students, though.

In the first case, this is certainly wrong. [œ] is rounded, and the sound in “yan” is definitely not rounded. I suppose you could claim the lip rounding of “ü” influences the following vowel, but I still find it very strange to use a rounded vowel to represent this sound.

This is a matter of taste, I think. You can argue (as I have done) that the “i” in these syllables are slightly further back and more open than [i]. Very few people pronounce “lai” with a cardinal [i]. Still, I wouldn’t consider writing [i] instead wrong, just slightly less accurate.

This is fairly common and the normal way of doing it in modern IPA. The reason I didn’t write this in the article is that almost no students have seen [ɯ] before. It also fails to properly account for the fact that the “i” in these sounds is an apical vowel and not exactly identical to [ɯ] in the IPA chart. In other words, you need to also raise the tongue tip to produce a proper zi, ci, si. If you combine the cardinal [ɯ] with the initial, you won’t end up with good zi, ci, si. Still, I think [ɯ] is the best way of writing this sound!

I hope this makes things clearer!

Wow thanks for this long answer, it actually made things more clear. I was noticing some of those things before, like when I say 字 it don’t look like つ despite being both written the same with IPA (I know there’re symbols for that but the book didn’t use them :).

Considering that this didn’t affect my pronunciation I guess it was “good enough for students” like you said, still, I don’t like being left in the dust about how things actually work.

But even if there was such a thing as a perfect IPA transcription it could only take me so far, nothing beats actual audio but a vowel chart would be way more helpful, I looked for one and didn’t find any, which I think it’s a absurd considering that I can easily find vowel charts for very “unpopular” languages like Lao. Those Chinese linguists probably already made a bunch of those ones for every accent on China but it seems that they aren’t googleble, so if you had any of those please share with us!

Hi,

I saw there are some resources linked in the article already, but still decided to add mine here as well. If somebody is looking for a Pinyin table with audio that works great on mobile, I’ve created this guide here https://www.pinyin-guide.com/. Hope it helps some learners who find this via search!

Thanks and keep up the great work.

A great website! I’m currently learning Chinese as a beginner in Taiwan, and having an interest in linguistics, I was dissatisfied with the phonetics the schoolbook offers. So I searched for IPA for Chinese and got onto your website, which got me hooked for hours! Some additional observations:

By my own observations, and confirmed by my teacher, most -in and -ing (e.g. jintian and mingtian) pronounced the same in Taiwan, but different on the mainland.

The “e” in “feng li” (鳳梨 pineapple) sounds like an open o ⟨ɔ⟩ to me.

A Taiwanese friend pronounced dian (either 點 or 店) with an “r” sound after the n, and said this is general for some -ian. “Pleco” app gives “dianr” in some cases.

You have a typo in “the sound is farther backl in the second word”.

Your comments 2014-07-09 at 15:29 and 2014-07-09 at 15:35 are the same?

Yes, but standard Taiwanese Mandarin does make a clear difference, although many people don’t make the distinction. Most teachers do and you wouldn’t pass any pronunciation exam with a merge. The difference is usually more pronounced in northern China, though, so it’s much easier to hear.

Yes, this is also common in Taiwan, but again not part of the standard pronunciation.

This is common in northern China, but not in Taiwan where very few people use 兒化音 (which is what this is called) in natural conversations. In almost all cases, you can remove the r and it means exactly the same thing.

Fixed! Thanks for pointing this out. 🙂

“I think most people will have already learnt this in their first week in class” so glad I found this article because nope my mandarin teacher never introduced me to this. I’ve found that with teachers who are only temporary/won’t be with the same class for more than a year, they’re not as worried about accurate pronunciation as they are about being conversational. First lesson for me was just hello goodbye and all that and I was never taught the technicalities of pronunciation so thats why im here trying to find it now! Would you ever considering putting together your info on pronunciation (even the stuff at the start you said was too basic to go into) to make a sort of master post of all mandarin pronunciation details for beginners with sketchy teachers?

Hi, these links seem broken: “Pinyin table with sounds” and “All syllables in Chinese, including tones”. Could you find the correct urls? Thanks for this useful post!

Thank you for letting me know! I have updated the link so it now goes to the Chinese Pronunciation Wiki, which is overall a much better resource than the one I originally linked to!

Very useful, thanks! In turn, I’d like to suggest some technical improvements.

1. The link to “Traditional Pinyin table in IPA” is out of date.

2. The link to “All syllables in Chinese, including tones” is redirecting to the main page. The same is with two links in https://chinese.stackexchange.com/questions/2479/how-is-the-pinyin-iu-pronounced/2484#2484.

3. The audio for “dui, tui, shui” is the audio for “tui, shui, sui” instead.

Just to make the post excellent. 🙂

And a very minor one: “Pinyin chart with audio” is a bit incorrectly formatted. 🙂

Thank you for pointing these things out! I have fixed the problems and changed/deleted/updated the links. I appreciate that you took the time to comment, because many people must have seen this but you’re the first one to leave a comment about it. 🙂

Hi,

I think there’s 2 broken links, I’m not sure :

1- chē in “Letter i”

2- nǚ in “Letter u”

Both don’t lead to audio clips like the other sounds links,

Thanks.

Excellent catch! I have updated the links so that they now lead to the correct audio files. Thank you for letting me know so I could fix the issue!

You’re so welcome,

It’s not a big deal i think, but one of the nǚ in “Letter u” is still not working, the one in “Listen” to be exact, the other one was fix thou…thanks a lot.

Thanks again! I missed your comment earlier, but I’ve updated that link now, too.

Which system would you think has the least number of pitfalls to an American learner? If there were no political ramifications, would you use Yale or Tongyong?

If transparency is the goal, IPA is the only good option!