The goal of studying foreign languages used to be reading and translation, at least if we’re talking about institutional learning, but a more modern, communicative approach has taken over in many educational systems. Language is seen as a means to communicate with other people, and your ability is determined by what you can do in the language, not what you know about it.

This is a welcome change, as it’s more aligned with most people’s motivation for learning languages. Furthermore, while translation requires understanding, it’s not true that someone who understands is necessarily good at translating, and the written language is only one aspect of the whole.

So, if we assume that the goal of learning Chinese is to be able to communicate in Chinese, students sometimes ask if accuracy matters.

- If the other person understands what I want to order in a restaurant, what does it matter if my tones are wrong?

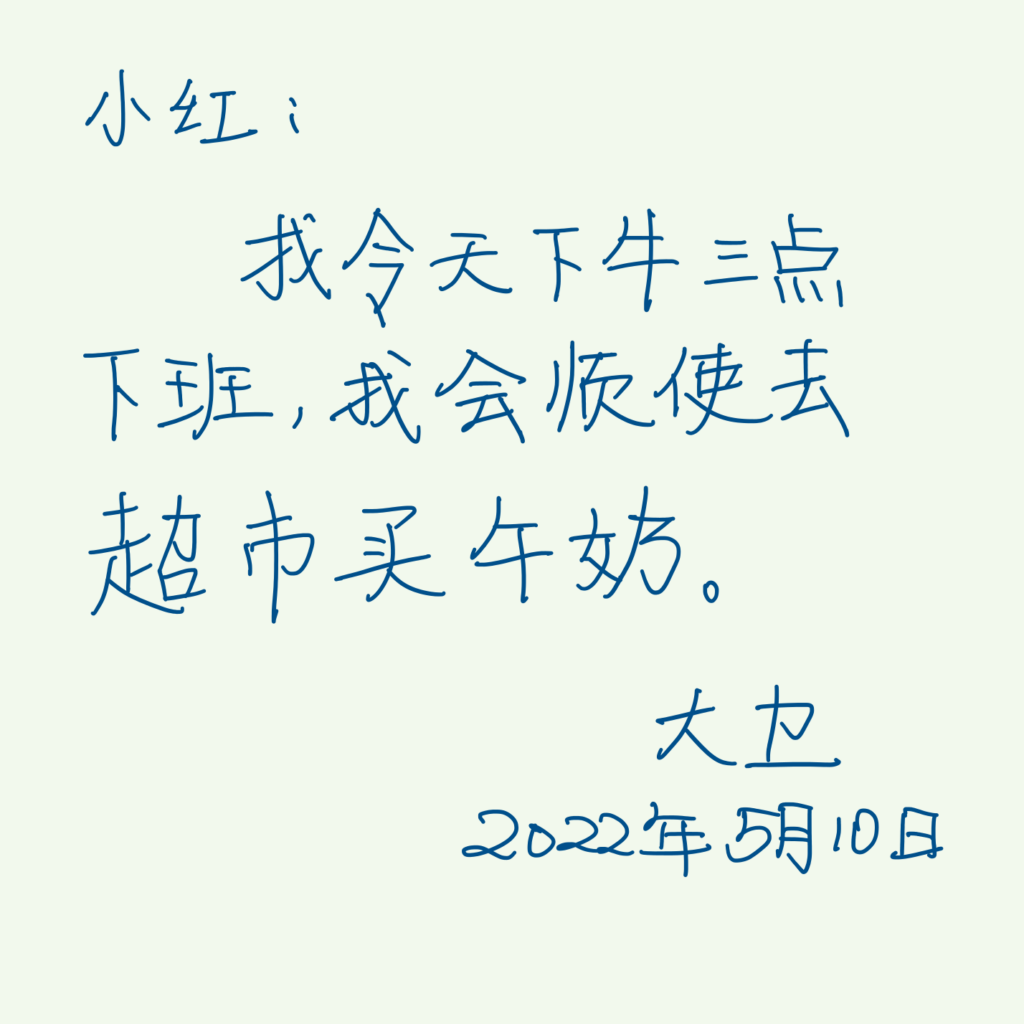

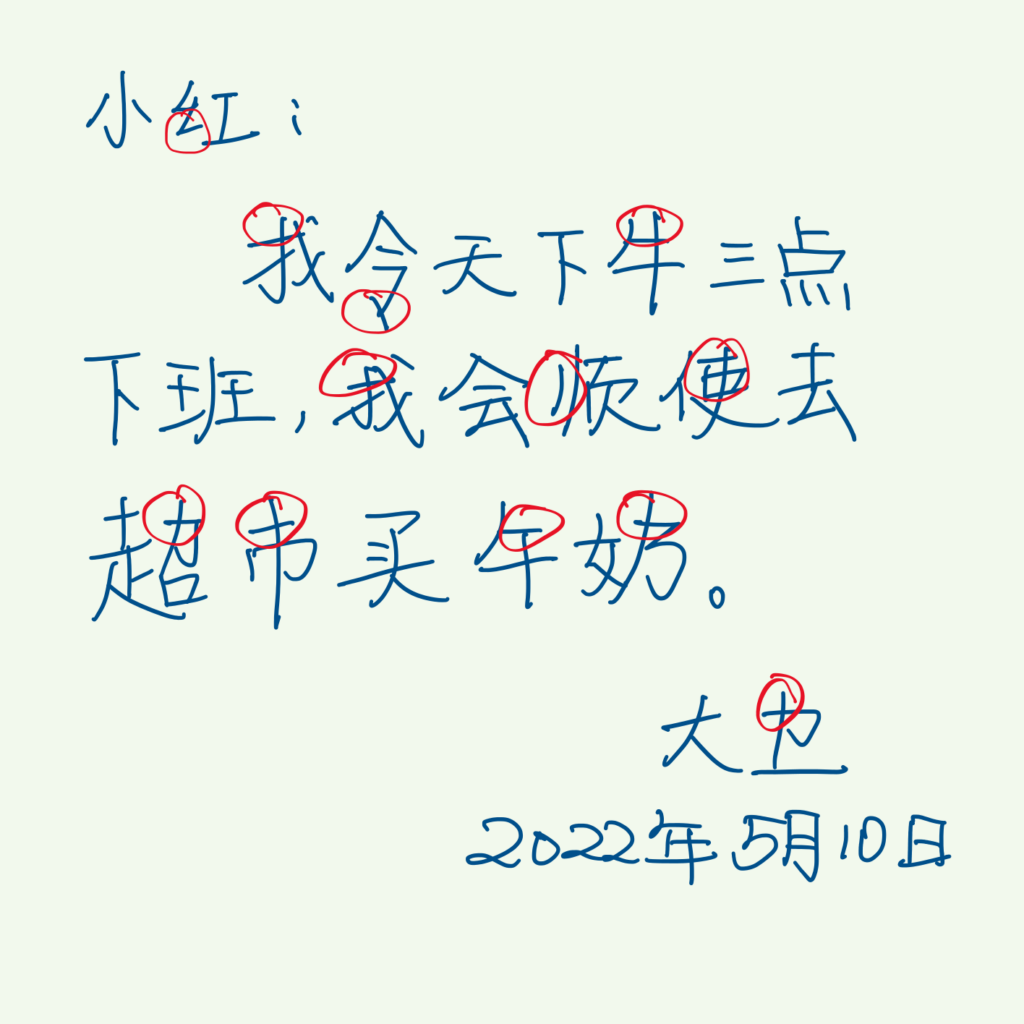

- If my landlord can read the note I left on her door, does it matter if some characters were written incorrectly?

- Is it okay if emails to my colleagues use strange word order, provided that they understand what I mean?

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

On accuracy, communication and comprehensibility when learning Chinese

There are many ways of approaching these questions. For example, there has been (and still is) much debate over how serious errors are when learning a language. Some people say that errors are not important as long as the other person understands what you want to say, but others say that errors are serious and that you should avoid them, lest they’ll fossilise and hard to fix later. I’ve written more about fossilisation and why I don’t like the term here.

Another aspect of errors is to note that people generally do judge books by their covers, so your pronunciation and handwriting do influence how other people regard you, however unfairly. I wrote more about this here when it comes to pronunciation. This is much less important than other aspects, but it’s still worth mentioning.

In this article, I’m not going to try to find an answer to the above questions, but I will discuss the role of errors when it comes to communication. Some people make the mistake of contrasting communication with accuracy, thinking that because the goal is to communicate, accuracy is not necessary. This contrast makes sense when choosing or designing learning activities, so you decide in advance to practice one or the other, but they are not each other’s opposite. Others go too far in the other direction, putting accuracy as the main goal of language learning.

Sometimes errors don’t influence communication at all

Sometimes, isolated errors will have little or no impact on your ability to communicate. Usually, if you write a character incorrectly or even if you choose the wrong character (a typo), people will still understand what you mean. The same goes for isolated pronunciation mistakes. I say “usually”, because even isolated errors on key elements of an utterance can definitely hinder communication! I’ll have to write an article about that some day, but it’s hard to collect good examples.

It’s not hard to find examples of the opposite though, of how errors don’t influence communication much. People are good at reading words even with egregious typos in them, for example. In fact, we can even read texts where the letters in the middle of words are mixed up, even though though it’s certainly not true that we only read tho first and last letters of words. Btu yuo cna porablby raed tihs. And if you read quickly enough, you might not even notice the weird spelling. Here’s a decent overview of this phenomenon, including the viral email I think most of you have seen.

Chinese characters with additional strokes and swapped components are sometimes readable

When it comes to Chinese, it’s often possible to replace certain components or write them incorrectly and still be understood. Not only that, but proficient readers might not even notice that you have written the wrong component! There’s an excellent post about this over at The Hexacoto: The persistence of comprehension (credit to John Pasden for bringing this to my attention back in 2014). You can see an example here, which is perfectly readable, even though it has lots of extra strokes that result in incorrect or entirely made-up characters:

View this post on Instagram

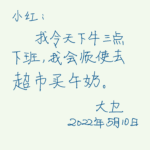

And here’s the cover image for this article again, with considerably smaller (and more realistic) errors in handwriting. As a fun exercise, see if you can spot the errors! Hint: There are 12 errors.

Here’s the same image with errors highlighted:

Sometimes errors really do affect communication

Examples like these should not be taken as a blank cheque to ignore accuracy completely. If you dig deeper into to the orthographic examples, you’ll find that only certain types of scrambles are allowed, and that we’re only talking about specific errors, such as spelling, not several types of errors at once. Also, the examples above are visual, and even though it’s probably possible to create somewhat similar examples in spoken language (speaking very quickly and deliberately using weird sounds on heavily reduced syllables, for example), listening is not chunked in the same way as reading is.

The reason some people are amazed by these examples is probably that they overlook the importance of top-down processing. Understanding comes in the shape of models we build as we read and listen, but these are heavily based on what we know and what we expect to encounter. As long as what we hear and see don’t deviate too much, we’re able to accommodate minor differences.

However, the more and the bigger the differences are, the more likely it is that our top-down processes fail. A good example of this is that the importance of accuracy is inversely proportional to the predictability of what you say or write, or in other words, if it’s easy to guess what you want to say based on context, you can make a lot of errors before people misunderstand. I wrote more about this here when it comes to tones: The importance of tones is inversely proportional to the predictability of what you say.

The importance of tones is inversely proportional to the predictability of what you say

The number and type of errors can make understanding difficult

So, the main reason all this is not proof that you can ignore accuracy is that the problem for learners of Chinese is not isolated errors, Instead, our output (speaking or writing) is filled with errors of different kinds and degrees of severity. It’s not a matter of the occasional tone mistake, but also problems with some initials and finals, maybe a stilted prosody, somewhat strange word order and frequent word choice issues. Small errors compound and make your output significantly harder to understand.

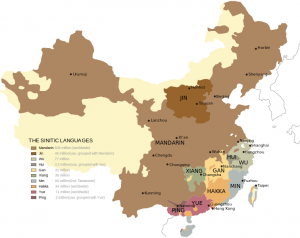

It also matters what type of errors you make. Readers and listeners have somewhat flexible models for how the language works, so native speakers don’t find it difficult to understand people from other regions, provided that they have had some exposure to it. This goes for learners as well. If you’ve only ever studied Chinese with people born and raised in Shanghai, you will find it hard to understand someone from Dongbei, and vice versa, but if you’ve had some exposure to these accents, you’ll be okay. Read more here: Learning to understand regionally accented Mandarin.

You can probably find good analogies in your native language: I find it very easy to understand people speaking Swedish with an English accent because I had a maths teacher in high school who spoke like that and I’ve met many other native English-speakers in Sweden. It’s much harder if someone has an accent I’ve never heard before.

This is true for the written language as well. Most learners find it difficult to read native handwriting because it’s not as neat as the characters used in printed textbooks and the characters the teacher writes on the board, but that doesn’t mean that native speakers find it difficult, because they take largely the same shortcuts and write in similar ways. If you as a learner were to make up your own semi-cursive Chinese handwriting, however, it would be very hard to understand.

Standard Chinese and what happens when you deviate from it

That means that there are several possible relationships with the standard forms in both spoken and written Chinese:

You follow the standard completely. This is normally the goal for most students and generally speaking something desirable as it has the highest chance of being easy to understand, even though there are exceptions in specific cases. I wrote more about this regarding pronunciation here: Standard pronunciation in Chinese and why you want it.

You follow the standard completely. This is normally the goal for most students and generally speaking something desirable as it has the highest chance of being easy to understand, even though there are exceptions in specific cases. I wrote more about this regarding pronunciation here: Standard pronunciation in Chinese and why you want it. You deviate from the standard in a well-known way. This would be the case of a native speaker with an accent. Other native speakers are used to this and will not find it very hard to understand, even if some errors might seem serious to us language learners (such as mixing up f and h, for example). See the post I linked to above about regionally accented Mandarin.

You deviate from the standard in a well-known way. This would be the case of a native speaker with an accent. Other native speakers are used to this and will not find it very hard to understand, even if some errors might seem serious to us language learners (such as mixing up f and h, for example). See the post I linked to above about regionally accented Mandarin. You deviate from the standard in your own idiosyncratic way. Most native speakers are not used to hearing foreigners speak Mandarin, so most errors will not be familiar to them, which also means that they will be harder to understand. An exception to this is if you speak to an experienced teacher. They are often accustomed to hearing students speak and will find it significantly easier to understand what you say that the average native speaker you meet. It’s common to hear from students that they can communicate perfectly well with their teacher, but struggle with basic conversations outside the classroom.

You deviate from the standard in your own idiosyncratic way. Most native speakers are not used to hearing foreigners speak Mandarin, so most errors will not be familiar to them, which also means that they will be harder to understand. An exception to this is if you speak to an experienced teacher. They are often accustomed to hearing students speak and will find it significantly easier to understand what you say that the average native speaker you meet. It’s common to hear from students that they can communicate perfectly well with their teacher, but struggle with basic conversations outside the classroom.

It’s clear that some, but not perfect, accuracy is needed to communicate successfully. It should also be clear that there’s much more to learning Chinese than being accurate, which raises the question of how to deal with all this as a learner. This is a big topic I won’t be able to cover in this article, but which I might return to later if people are interested in hearing my thoughts about it, but let’s say at least something about it here as well.

Caring too much about accuracy is bad for your Chinese

On the one hand, we have teachers and students who mostly care about accuracy. This will lead to much anxiety and slow progress towards communicative goals, as accuracy is only a small part of the overall equation. As I have argued many times in different ways, quantity often beats quality when it comes to languages. It’s much better to know twenty words poorly than to know one word perfectly, at least if your goal is to communicate with other people. I wrote more about this here: Learning Chinese words: When quantity beats quality.

Also, if you spend too much time on accuracy, you miss out on communicative strategies, which you definitely need when interacting with real people. What do you say when you don’t understand? How do you deal with breakdowns in communication? How do you communicate even when your language is clearly not up to the task? These things are certainly possible, but they require some practice, and you simply won’t get that if you only stick to safe language you’re sure to be able to use accurately.

Not caring about accuracy is all isn’t ideal either

On the other hand, not caring about accuracy at all can have certain consequences, and repeatedly making the same error or mispronouncing the same tone will make it harder to fix these problems later. As I’ve argued above, it’s also the case that the more advanced your Chinese becomes, the higher the demands on accuracy will be. I have met many students who were rather happy with their level of accuracy until they needed to use Chinese for something other than everyday life, at which point they realised that they’d missed out on much and needed to go back to the basics.

This is not an argument for or against enrolling in a Chinese course (I’ve discussed that in detail here), as there are courses that don’t focus much on accuracy at all and others obsess over it, and there are independent learners who don’t mind making mistakes and others who very much do.

Should you enrol in a Chinese course or are you better off learning on your own?

Figuring out where you are on the spectrum can help you reach your goals

However, it’s important to figure out where on the spectrum you are as a learner and consider if it’s worth moving towards the centre. If you’re in a course where every single error is pointed out and fixed, but you rarely have the chance to use Chinese to actually communicate, you should probably switch to another course or at least make sure that you get more realistic communicative practice on the side. If you’re in a situation where you get no feedback at all regarding accuracy beyond if people understand you or not, you’d probably benefit from a small dose of that, if nothing else then at least to make sure your Chinese is as good as you think it is, so you don’t end up wondering why your Chinese isn’t as good as you think it ought to be

Then we also have the debate about the role of feedback, instruction and input when it comes to building accurate mental models for the Chinese language in your brain, but this article is already long enough. I will point the curious to a couple of related articles though:

- How to get honest feedback to boost your Chinese speaking and writing

- An introduction to comprehension-based Chinese teaching and learning

- An introduction to extensive reading for Chinese learners

How to get honest feedback to boost your Chinese speaking and writing

An introduction to comprehension-based Chinese teaching and learning

https://www.hackingchinese.com/introduction-extensive-reading-chinese-learners/