There is no perfect method for learning Chinese. Instead, methods can be good in some ways and bad in others.

There is no perfect method for learning Chinese. Instead, methods can be good in some ways and bad in others.

The best method would be one that is efficient and fun, while also focusing on just the right content, but such methods are elusive.

Instead, increasing one factor often comes at the cost of another factor. How can you deal with this as learners of Chinese?

For example, what happens if you find a method that everybody swears by, but you truly hate it? Or the opposite, what if you enjoy using a method that isn’t good for some other reason?

These are two questions I will explore in this article!

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

What is a good method for learning Chinese anyway?

What is a good method for learning Chinese? An intuitive answer might be:

“A method that helps you learn the language.”

This doesn’t add any information that wasn’t already present in the question, however. Let’s try again:

“A good method for learning Chinese is one that helps you reach your goals for learning the language.”

This is much better, at least if you’re clear about what your goal is and what you need to learn to get there, but we still need to dig deeper to see in what way the method helps you reach your goal!

A method for learning Chinese can be good in three ways

A method can be good in at least three ways:

By helping you learn the content (vocabulary, grammar, etc.) required to reach your goal. For example, if your goal is to converse with business partners in Chinese, a method that exposes you to spoken language used in that context is better than one that focuses on writing characters by hand from a frequency list. Learning the right things is important!

By helping you learn the content (vocabulary, grammar, etc.) required to reach your goal. For example, if your goal is to converse with business partners in Chinese, a method that exposes you to spoken language used in that context is better than one that focuses on writing characters by hand from a frequency list. Learning the right things is important! By being efficient, meaning that using one method for an hour brings you closer to your goal than spending an hour using a different method. For example, if your goal really is to be able to write characters by hand, then flashcards is a much better method than copying the same character over and over.

By being efficient, meaning that using one method for an hour brings you closer to your goal than spending an hour using a different method. For example, if your goal really is to be able to write characters by hand, then flashcards is a much better method than copying the same character over and over. By enabling you to spend more time because learning is more enjoyable or interesting compared to other methods. Even if you study the right things and use the most efficient method, you won’t learn anything if you don’t invest enough time. Thus, a good method is a method that you are willing to use and use a lot.

By enabling you to spend more time because learning is more enjoyable or interesting compared to other methods. Even if you study the right things and use the most efficient method, you won’t learn anything if you don’t invest enough time. Thus, a good method is a method that you are willing to use and use a lot.

To learn as much as possible, you need to optimise all three of the above factors. This is something I’ve dedicated an entire article to; check it out here: Three factors that decide how much Chinese you learn.

Most methods for learning Chinese are both good and bad

Let’s have a look at a few concrete examples of methods for learning Chinese that are good in some regards, but not others. Naturally, much of this comes down to personal preference, so these specific examples might not apply to all of you, but I’ve chosen examples based on what I see and hear from students.

Flashcards are efficient, but not fun. Flashcards rely on two psychological effects that are extremely powerful for learning in general: spaced repetition and active recall. This makes flashcards great for learning some things, such as Chinese characters. But what if you have tried flashcards and hate them? Should you force yourself to use them, or should you find other methods, even if they might be less efficient?

Flashcards are efficient, but not fun. Flashcards rely on two psychological effects that are extremely powerful for learning in general: spaced repetition and active recall. This makes flashcards great for learning some things, such as Chinese characters. But what if you have tried flashcards and hate them? Should you force yourself to use them, or should you find other methods, even if they might be less efficient? Listening to Chinese learner podcasts with lots of English in them is not efficient, but it’s more relaxing than Chinese-only alternatives. Should you ditch these podcasts even though you like the hosts and think you’re learning some Chinese at least? You’d get more out of each hour you spend, but on the other hand, you might listen for fewer hours in total.

Listening to Chinese learner podcasts with lots of English in them is not efficient, but it’s more relaxing than Chinese-only alternatives. Should you ditch these podcasts even though you like the hosts and think you’re learning some Chinese at least? You’d get more out of each hour you spend, but on the other hand, you might listen for fewer hours in total. Talking with a familiar person is easier than talking to a stranger but won’t teach you as much. If you want to level up your listening ability, you should expose yourself to a broader range of Chinese. The question is, should you switch teachers regularly and constantly seek out new language exchange partners, even if you get along perfectly well with those you have now?

Talking with a familiar person is easier than talking to a stranger but won’t teach you as much. If you want to level up your listening ability, you should expose yourself to a broader range of Chinese. The question is, should you switch teachers regularly and constantly seek out new language exchange partners, even if you get along perfectly well with those you have now? Reading about topics that genuinely interest you is great for motivation but might be forbiddingly difficult. Unless you’re already at an advanced level, most topics outside learner materials will be hard, meaning that reading about them is intensive reading, rather than extensive reading. One thing I really wish I had done less of is to read texts that are too hard, but what if the only texts you find interesting are also very hard?

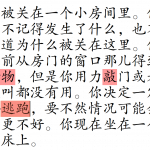

Reading about topics that genuinely interest you is great for motivation but might be forbiddingly difficult. Unless you’re already at an advanced level, most topics outside learner materials will be hard, meaning that reading about them is intensive reading, rather than extensive reading. One thing I really wish I had done less of is to read texts that are too hard, but what if the only texts you find interesting are also very hard? Leaving your comfort zone will help you learn more but is, by definition, uncomfortable. I’ve never made quicker progress with listening ability than when thrown into a new immersion environment, but the experience is far from enjoyable. Should you push yourself to immerse more even though it makes you feel frustrated?

Leaving your comfort zone will help you learn more but is, by definition, uncomfortable. I’ve never made quicker progress with listening ability than when thrown into a new immersion environment, but the experience is far from enjoyable. Should you push yourself to immerse more even though it makes you feel frustrated?

I could make this list longer, but I think it’s clear enough that there are many situations where you must weigh something being good for your Chinese against how much you enjoy doing it.

Having fun is essential, but it’s usually not the main goal

While it’s certainly true that it doesn’t matter how good a method is if you don’t use it, how much you enjoy something can’t be the only factor for determining if it’s a good method for learning Chinese.

This would lead to absurd choices of method, because “eating cookies”, “sleeping in on the weekend” and “watching cute kittens on YouTube” might all be enjoyable, but these activities don’t bring you any closer to your goal for learning Chinese.

This becomes even trickier for teachers, because now you must make this choice for your students. Should you persist in speaking mostly in Chinese to beginners because you know that’s by far the best way for them to learn, even if the students complain that they think your lessons are too hard?

I’m not even going to try to answer all the questions posed above in this article, but I am going to discuss the problem in general and the trade-offs between efficient and enjoyable methods for learning Chinese.

Always try a method thoroughly before deciding if it’s for you

It’s one thing to read about a method and another to have tried it yourself. This works both ways, so methods that sound fun might turn out to be tedious, and methods that sound weird might turn out to be awesome. Don’t just read about language learning methods, try them!

I recently listened to a podcast where the hosts had no experience of memory techniques, and after interviewing memory champion, discarded most of the strategies discussed in the interview because they sounded bizarre. That made me a bit sad. If they had tried out mnemonics themselves, I think they would have reached a different conclusion. Remembering really is a skill you can learn.

Do you like the method? How effective is it?

Once you’ve given the method a fair chance, it’s time to take a step back and analyse your situation. Ask yourself hone of these questions, depending on the case:

- How much do you love the method? How inefficient is it?

- How much do you hate the method? How efficient is it?

While this is not necessarily a simple education where enough plus signs on one side balances minus signs on the other, it’s important to pay attention to if you just feel lukewarm about a method or hate it with a passion. Similarly, some methods might only be slightly better than others, in which case what you think about them should be the determining factor.

Save boring but efficient methods for limited cases

If you dislike flashcards but realise that they can be extremely good for memorising certain things, limit your use of flashcards to only these things.

Explore ways of making flashcards less tedious, such as trying different software, spreading out reviews over the day or even using paper flashcards.

Add only flashcards for things that don’t seem to stick using other methods; delete anything you later realise you don’t need.

Similarly, if you don’t like creating fanciful mnemonics to memorise characters but realise that this can be useful in some cases, then don’t create mnemonics for every part of every character you learn. This is not even a good idea if you like mnemonics!

Understand why a method is useful

It’s often good to dig a little deeper than the basic description of how a method works. I’ve mentioned flashcards a few times in this article, and I have also mentioned two factors that make flashcards work: spaced repetition and active recall, but do you know what those are and why they are helpful?

I explain both in my review of Skritter, a flashcard learning Chinese characters, in this way:

- Active recall means that when reviewing, you do so by actively searching your long-term memory for the right answer. It’s a well-established fact that just seeing the right answer is a bad way of reviewing. Similarly, writing a character while looking at a model character does very little for your long-term memory. So, instead of just staring at the character 我 and hoping you will remember it, you need to ask yourself a question: How do I write the character that means “I; me” in Chinese? Then you write it from memory. Successfully remembering how to write it leaves gradually stronger memory traces.

- Spaced repetition means that rather than asking yourself how a certain character is written repeatedly in a short period of time, you space (spread) the reviews out over days, weeks and months. This has been shown to be many times more efficient than massing repetitions together. You can further boost efficiency by gradually increasing the spacing between each review, so the better you know a character, the less often you review it.

By understanding why and how the method works, you might find that it’s also more interesting to use. Sometimes, using a method is more motivating simply because you know it’s good for you!

This is also the main reason articles on Hacking Chinese tend to be long. I want you to understand why I’m recommending something, not just tell you what to do. You should be in charge of your own learning, and that requires some understanding of the methods you use.

Find other ways of repairing the benefits of efficient but boring methods

When you understand the method on a deeper level, you can start looking around for other methods that rely on the same principles but might be more interesting

For example, spaced repetition is not limited to flashcards. Extensive reading and listening are natural ways of spreading exposure to vocabulary out over time and can be even better than using a vocabulary app!

Read more about this example in this guest post: Reading is a lot like spaced repetition, only better.

What about enjoyable but inefficient methods for learning Chinese?

Now that we have looked at efficient but boring methods, let’s look at the other scenario: methods that you enjoy, bu not good for other reasons. This is related to infotainment in general, where what’s entertaining is often more popular than what provides the best information.

Again, I don’t mean to imply that there is a simple equation for calculating how good a method is for you, but magnitude matters here as well. Listening to a podcast which is mostly in English really won’t help you improve your listening ability much, so you must love the hosts an awful lot to make it a good method for learning Chinese.

To put it briefly, a decrease in efficiency must be balanced by a corresponding increase in the amount of time you’re willing to spend. Since this time could have been spent on more efficient ways of learning, you should be careful with “fun but bad” methods.

How much do you care about reaching your goals? At what cost?

As I have said several times already, we are all different. Some learn Chinese mostly because they enjoy it, others learn because they must; most are somewhere in between.

- If you care a lot about reaching your goals quickly, you don’t have time for inefficient methods, even if they are pleasurable.

- If you’re mostly learning Chinese for fun, efficiency becomes less important, and even a slight drop in how enjoyable a method is might be enough to discard it in favour of a more fun way of learning.

Some learners are extremely motivated and don’t mind if a method is a bit boring as long as it gets the job done, others are sensitive and might quit learning Chinese altogether if the experience is too tedious.

Conclusion: Explore, experiment, enhance

To summarise, explore different methods, experiment with them in your own learning routine, and constantly strive to enhance the way you learn. I know this is not as clear advice as some of you want, but you really are the only person who can and should decide what works for you.