If you look online for an answer to the question of how important tones are when learning Chinese, you typically find two types of answers:

If you look online for an answer to the question of how important tones are when learning Chinese, you typically find two types of answers:

Tones are essential and you should make sure to learn them properly from the start.

Or:

Tones actually don’t matter that much and even native speakers don’t really use them.

I have so far never seen anyone with some training in Mandarin phonology claim that tones are not important, and it’s also exceedingly rare for teachers to hold this view. The reason is that tones actually are important, so this is the correct answer.

Still, there are people out there who believe that tones aren’t that important. It would be easy to just dismiss this as being ignorant, but I think there’s more to it than that.

Why does this misconception persist?

Why would otherwise sensible people claim something that is outright wrong?

In this article, I will explore a number of things that might explain this and also show some interesting things speaking and listening ability.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many other platforms!

Let’s start with what I believe is the main reason tones are underestimated by learners:

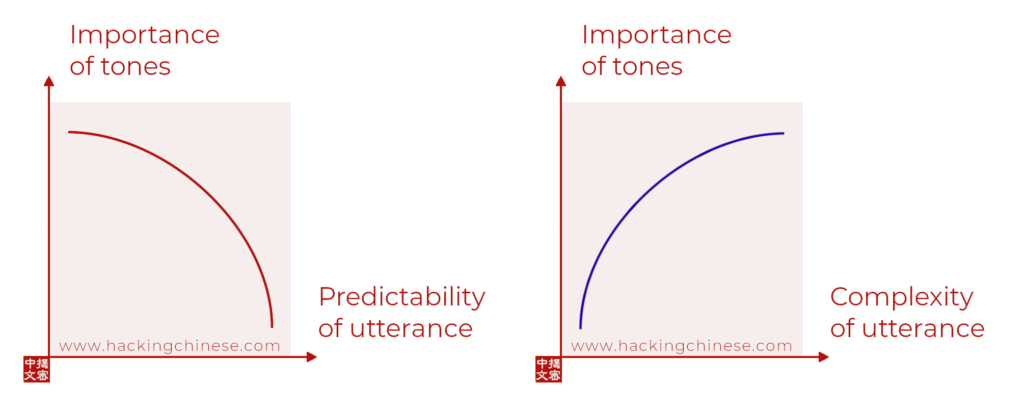

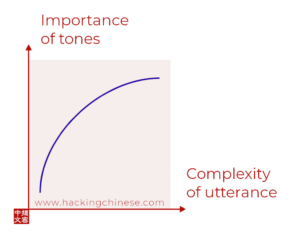

The importance of Mandarin tones is inversely proportional to the predictability of what you say

The graph on the right shows what this statement means. The more predictable an utterance is, the less important tones become, and vice versa: the less predictable an utterance is, the more important tones become.

The graph on the right shows what this statement means. The more predictable an utterance is, the less important tones become, and vice versa: the less predictable an utterance is, the more important tones become.

Let’s look at two examples before I explain why this is the case and what it means.

- High predictability context: Going to the airport – You’re standing outside one of the most popular hotels for foreigners in the city, looking for a taxi to take you to the airport. You have a big suitcase with you. An empty taxi is prowling along the street and you hail it. The driver helps you with your luggage and you say that you want to go to the airport in your best Mandarin. He nods and off you go. In this situation, you’re like to get away with a lot in terms of tone issues. While it could be that you want to go to the train station and not the airport, the driver almost knows what you’re going to say before you open your mouth. You could speak Swedish with him and he might still understand. This is a good example of a high-context situation where tones don’t matter much.

- Low predictability context: Going to your friends house – Let’s look at a situation that looks similar, but is actually completely different. You’re hailing a cab, but this time without your luggage, and this time your destination is a friend’s house five kilometres away in an area of the city where few foreigners ever go. It’s also on a street with a name that isn’t all that commonly used (so not 南京路 or something like that). You do your best to pronounce the street name, but you probably got one or two tones wrong. The driver looks confused. You try again. And again. And again. Finally, you manage to find the name on your phone and show it to him. He smiles, says something that to you sounds exactly like what you just said and off you go. In this case the driver has no context whatsoever to go on and if you get even one tone wrong, he might be unable to guess which street you want to go to. This is a good example of a low-context situation where tones matter a lot.

It’s easy to see how these different scenarios can give rise to different ideas about the importance of tones. If you often find yourself in the first type of situation, you might draw the conclusion that you can get away with bad tones, but if you’re using Chinese in a wider range of contexts, you’ll quickly realise that tones really are important.

To be honest, most people who claim that tones are not important are themselves students. Either they have mostly used Mandarin in high-context situations or they are simply unable to evaluate how other people use tones when speaking Chinese, including native speakers, thus thinking that they don’t use tones in natural conversations (they do of course, more about this below). This misconception can be further enhanced if native speakers praise the student’s pronunciation, even if it’s actually quite bad, giving rise to a false sense of competence.

Another common misconception is that speaking quicker somehow makers your Chinese better. It might if your goal is to fool someone who’s ability is much lower than yours, but you certainly don’t fool native speakers! If you want to sound like a native speaker, the key is not to speak quickly, but to follow the guidelines laid out in this article by David Moser:

Naturally, it’s easy to claim that tones are not important if you yourself don’t hear the tones. It would be like someone learning English mixing up “bitch” and “beach” and then claiming that it’s fine to ignore vowel difference like that, as long as you speak quickly enough.

That obviously isn’t true, but that is how it sounds when people claim tones are not important in Mandarin.

Real conversations occur between the two extremes

Of all realistic situations we might find ourselves in, saying the name of an unknown, obscure place in a big city is very unpredictable for the listener. People’s names are in the same league.

Most conversations don’t take place in this realm of extreme unpredictability, because there usually is more context to help the listener understand.

But most conversations aren’t like going to the airport either. What’s the purpose of having a conversation if you’re limited to saying things that the other person can guess before you say them? Clearly, you want to be able to communicate!

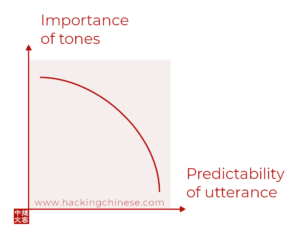

In general, the importance of tones increases in proportion with the complexity of what you’re saying.

In general, the importance of tones increases in proportion with the complexity of what you’re saying.

In particular, the number of words you use when you speak Chinese has a big impact on predictability. If you only know 200 words and have spoken with the same person for a while (maybe your teacher, partner or good friend), the guess-what-the-foreigner-is-saying game becomes quite easy, because there are limits to what you can say. However, if you know 20,000 words, it’s much harder.

The importance of tones also increases in proportion with the complexity of the message. If it would require mental effort to understand what you’re saying even if said perfectly by a native speaker, do you really want people to spend their cognitive resources trying to figure out what words you’re using?

Clearly not. Instead, the goal of learning pronunciation is to limit the distorting effect mistakes have on our ability to communicate.

Native tones in connected speech

Regarding the nonsense about native speakers not using tones, that is clearly just that: nonsense. Tones are an integral part of Mandarin phonology and they can’t be ignored more than vowels can.

That being said, pronunciation in connected speech is rarely exactly as it is taught in a classroom. This is true in any language, but how much speakers of that language are aware of it varies between individuals. Native speakers of English pronounce words in wildly different ways depending on context, so some variation is to be expected with tones in Mandarin as well. Most native speakers are not aware of this!

Most of these changes in pronunciation are optional for speakers, though, and most of them come naturally with increased fluency in the language. The variation can make it harder to understand and learn initially, but that doesn’t mean that tones aren’t there, or that they are morphed beyond recognition in most cases. The only such case is the third tone, which I have covered in a separate article:

I’ve been meaning to write an article about tones in connected speech for almost a decade now, but in the meantime, check this article from John Pasden over at Sinosplice: Seeing the Tones of Mandarin Chinese with Praat. I have spent literally hundreds of hours in Praat looking at native and non-native pronunciation, and believe me, the tones are definitely there!

Not just tones

In fact, this argument can be made for anything related to speaking and accuracy, such as initials, finals, words choice, grammar and more. The more context, the less accurate you need to be to make yourself understood. The reason is that when we listen to someone talking, we must rely on two different kinds of processing:

- Bottom-up processing extracts information from an utterance itself, perceiving and categorising sounds, parsing the linguistic information in them and connecting them to words and meaning stored in long-term memory. When listening to a second language learner, this processing can run into problems, simply because the utterance itself contains errors. However, the listener doesn’t rely only on bottom-up processing.

- Top-down processing starts with things you know and provides a framework where known information can be reconciled with the information extracted via bottom-up processing. The listener can draw on knowledge about the situation and the language to predict or guess what the other person is saying. In fact, we do this all the time even when listening to our native language.

We use both these types of processes all the time when listening, and listening wouldn’t be possible without them. Experienced listeners will be able to make sense of what you say as a second language learner, even if you make mistakes, provided that they can employ knowledge about context and language to fill in the gaps. The more serious the mistakes and/or the less context is available, the more likely it is that the listener fails to understand.

Tones are more important than most people think

I suppose this was just a rather long-winded way of saying that tones are important. Don’t overlook tones. Don’t think you’ve mastered tones after studying for a semester or two, because it’s unlikely that you have. Don’t believe people who say you shouldn’t bother with tones or that you can learn them later.

The fact that your teacher, good friend or partner seems to understand what you say most of the time when using basic sentences is not a stamp of approval saying your tones are good enough.

Teachers are used to hearing foreigners speak Chinese and know roughly what you’re going to say. When you leave the classroom, bad tones will cause trouble.This doesn’t mean that you have to obsess about tones and avoid speaking at all, it just means that tones should be on your mind until you can confirm that you really know them. My favourite way of analysing tone problems is with the simple guessing game I have described in this article, why don’t you try it out next time you have a native speaker around?

Naturally, there’s more to learning Chinese than tones and pronunciation, but if it’s something you really shouldn’t overlook as a beginner or indeed intermediate learner, it’s tones.

A question to the reader: While I can explain the cognitive processes involved in listening comprehension in some depth, my theory about why people keep claiming tones are not important is just that: a theory.

What do you think? Why is it that some people maintain that tones aren’t that important? If you’re one of those people, what’s your counter-argument to what I’ve said here? Please leave a comment below!

Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence

This video course is for those who want to learn Mandarin pronunciation, from beginners who struggle with tones and Pinyin to more advanced learners who want to fix errors or polish their accent. Pronunciation is essential; get it right now and save yourself a ton of trouble later!

This video course is for those who want to learn Mandarin pronunciation, from beginners who struggle with tones and Pinyin to more advanced learners who want to fix errors or polish their accent. Pronunciation is essential; get it right now and save yourself a ton of trouble later!

The course only periodically opens for registration, but if it’s not open when you check it out, you can sign up to the waiting list to get notified when the course opens again.

More about tones on Hacking Chinese

- The Hacking Chinese guide to Mandarin tones

- Learning to hear the sounds and tones in Mandarin

- A smart method to discover problems with Chinese tones

- Learning the third tone in Mandarin Chinese

Editor’s note: This article, originally published in 2012, was rewritten and massively updated in June, 2021.

32 comments

I agree with all this completely. The analogy I use is that hearing the wrong tone is like hearing the wrong vowel sound- which as in English would be understandable in a simple and predictable situation, but would fail otherwise.

Spoken Mandarin has fewer possible syllables and relatively shorter words, so has a high degree of ambiguity when compared to English and other European languages. Both of these factors mean that context is more important anyway- 1 or 2 perfectly spoken mandarin words in isolation are difficult to work out anyway. Take away the tones, and the search space for the listener has increased to perhaps dozens or hundreds of possibilities for each syllable.

Pinyin input systems do pretty well at understanding which characters you intend in long sentences, but cannot guess if you only type 1 or 2 characters with no other context.

Do you use Quora much? A few days ago I wrote a similar critique of someone who claimed that tones weren’t important. We must be thinking on the same wavelength. 🙂

I live the consiseness of the title here. It describes perfectly how I feel about the importance of tones (and pronounciation and grammar as well!) in languages.

No, I don’t, but perhaps I should. 🙂 Yes, it’s true that what I say can be extended to anything, not just tones. I just feel that tones are particularly interesting in Chinese because it’s so easy to overlook their importance coming from a non-tonal language. I mean, we all (most of us at least) know that tones are important, but do we really feel it? There’s a difference between knowing it intellectually and actually feeling that it’s true.

When I initially began studying Chinese in Taiwan a few months ago I was very frustrated by tones, because I did not understand their importance to the native’s ear and because of the extra work they required. Hearing and speaking tones are not something you learn like vocabulary or sentence structure. It is more akin to acquiring a skill and there is a lot of embarrassment and correction in obtaining this skill.

To be honest, I was put off by tones because of laziness and a desire to advance more quickly. I have abandoned the naive idea of becoming fluent in a short period of time and have decided to let it take as long as it takes while enjoying the process. With that unnecessary pressure gone I feel free to give tones as much attention as they need.

For the record, I think tones are important and I like to order the occasional píjiǔ 🙂

This made me remember the time when my parents came to visit me in China, and as I was also attending classes, they had to walk around the city by themselves from time to time. And once they went to Macdonald’s and along with the main order which they showed on the picture, they tried to order tea in Chinese, because they knew that it sounds like cha. Only with the exception of the tone, and thus their version was much closer to the 4th tone and not the 2nd… they failed completely. The Chinese side didn’t understand even after them repeating it for 10 times xD though you would think it’s quite predictable here. But maybe poor Chinese guys was trying to figure out what is lacking… 😀

So even my parents which were a bit unbelieving about the tones had a proof that tones are absolutely important : )

As long as it makes people think that tones are important, I’m happy! Sure, context might not always give native speakers enough information to guess what someone is trying to say, but it does help. I just don’t want people to imagine that just because someone understands what they’re saying it automatically follows that tones and pronunciation is correct. Context can make up for sloppy pronunciation, but of course not all the time!

After 3,5 years of studying and several stays in China, I can nothing but approve your article. I can’t add anything, because I’ve experienced the same. Ppl with wrong tones are understood either because the other part can predict what he’s saying or/and because they’re used to speak with foreigners.

Thanks for this post! 🙂

Oh, wait. I think of something which makes it even harder to realize what someone is saying is wrong: overdosed praising!

I know that the intention is a good one, being friendly to guests etc. I don’t wanna value that Chinese behaviour.

But I want to stress that a person who isn’t enough self-aware of his abilities or even can’t here himself while he’s speaking (in order to compare that sound to another)could’t that way think his Chinese is flawless.

Yeah, praise is perhaps even a bigger problem. In fact, I have already addressed that in an article (Advancing in spite of praise). The crux is that the problem becomes more and more severe the better you get. Just because someone has never heard a foreigner speak so good doesn’t mean it’s good at all.

Great article and definitely true!

Street names can be tricky if they use a word not often used. Sometimes, I have to point a driver in the right direction with landmarks before he gets my meaning. This really does illustrate the prediction and ‘in context’ understanding.

I feel safer rambling off a well used sentence but lose confidence if and when I am only required to give a one word answer. It’s much easier to bury wrong tones in predicted sentence structure.

My favorite scenario is when an easily predictable conversation takes place between myself and a waitress in some small village restaurant and said worker gets totally thrown by hearing a foreigner speak Chinese. That seizure of thought process can throw ’em for a whack.

…Just the other day, I was in a HongQi and a five year old girl starting speaking to me and I responded in Chinese;

me: 你好小朋友。

child:啊,你说的什么我听不懂。

me: 你没听懂我敢说的什么?

child:啊,我听不懂。

me: 呢,你怎么能回答?

She’s got it in her mind no matter what that foreigners can’t speak so she can’t connect the dots that we are talking to each other.

On another note, even smaller children will automatically assume that you can understand, just like mommy and daddy.

Not sure where I got derailed but, I absolutely agree that tones are important! (sorry, my brain is fried)

Yes,tones are significantly vital in every Chinese dialect.it is so naturally a intergral part of the Chinese language that it is acquired without any conscisousness. The tones are in the same way to convey the very meaning of one word with the vowels. When a tone-adapted ear hear a sound with incorrcect tones,it can’t tell the accurate meaning unless the context can clearly speak itself.

the vowels accompanied with repective tones to tell and distinguish a specific meaning makes Chinese faster to spread out and be well received by a hearer.

Very good blog post. I absolutely love this site.

Keep writing!

I am learning chinese in Lesotho, Southern Africa and the one thing my instructors always put emphasis on is tones. At times you’d find that in class, we all use the same vocabulary but fail to understand each other because of tones. What makes things difficult here is the most chinese here are business people who aren’t really willing to speak chinese to any mosotho. How does one improve their listening skill towards differentiating tones?

By listening a lot to tones and focusing on them. Preferably, you should listen to different people, so don’t use only your textbook. If you use Anki or such programs, you can add audio to the vocabulary. Quantity is quite important. Know the difference between the tones in theory, then listen to as many different practical examples as possible. That should gradually allow you to hear the difference.

In my classes I ask students to record themselves and to mimic exactly the lesson phrases.

We do this rather than focus on individual character tones.

After just a few weeks of lessons they can correctly pick out (and reproduce) the tones from learned expressions.

We make clear from the outset that a character or phrase learned without the correct tone is building up serious difficulties for the future, material that will have to be unlearned and relearned correctly.

This is far less laborious than learning character by character. Plus the tonal adjustments are automatically incorporated.

It helps a lot that our learning platform allows them record and re-record sentences and that I can review these as their teacher.

So yes I agree with you completely, learn tones from the start and learn it correctly. Developing that mental space that stores a phrases tone is a new skill that needs to be learned at the get go.

Not knowing a new words tone needs to feel like trying to go asleep knowing you haven’t brushed your teeth.

Sounds like a good approach to me! Mimicking is, in my opinion, the best way to approach most pronunciation issues. It does differ a bit from student to student, though, some really don’t pick it up just by mimicking on their own. How old are your students? The younger they are, the better your approach works, I think. It also works best with beginners who haven’t already established bad habits. 🙂

Thank you. I will sure follow your advice.

It should be noted that not only context helps, but also how many syllables the word has an how many close homophones there are. If you say “malaixiya” or “kafei” in any alien tone you will still be understood simply because there is no other “kafei” than the coffee “kafei” itself and the Malaysian country.

To show how tones are important to my students, I always use the “wo mai huar” example, in which you may mean “I buy flowers”, “I sell flowers”, “I buy pictures” and “I sell pictures”.

Although I agree with the premise of this article, in my experience studying in China those foreigners who were most fluent in Chinese had awful pronunciation and when asked about their tones admitted not paying much attention and advised us to just “speak fast and they will understand” whilst those of us who tried to get tones right were often not making much progress :/ From what I saw it was quite rare to find fluent speakers who had nailed tones. Bit difficult to find a balance

You mean “fluent” as in “speaking without interruption”, I assume? Yes, that’s definitely easier to do if you don’t care about accuracy at all! The balancing act you mention is real, though. Obviously, we can’t make sure that everything we say is 100% correct before we say it, that way we will get nothing said, but even if the opposite is better, it’s not the ideal either. I think the solution is rather simple, though, just separate meaning-oriented practice (conversations) from form-focused practice (such as mimicking to improve pronunciation). In most areas and situations, meaning takes precedence, but it’s quite clear than “just speaking” doesn’t really lead to good pronunciation in most cases. I also think pronunciation is a lot about caring and paying attention, which will lead to gradual progress over time.

Interesting discussion. It got me wondering if one could use Google translate or Dear translate to practice pronunciation including tones. I first said to Google translate:

关于这个东西,我没有那么熟。I am not sure if this is a correct sentence in Chinese but the translation was OK. Then I repeated the same sentence while deliberately getting the tone wrong in 熟. It worked and I had 树 instead of 熟 : 关于这个东西,我没有那么树.

I actually wrote two articles about this exact topic a while back, checking how good it would be to use the Android or iOS speech recognition for practising pronunciation. You can check out the first part here:

Using speech recognition to improve Chinese pronunciation, part 1