This is a guest post about reading in Chinese, written by Sara K. Reading is one of the best ways of picking up new vocabulary once we reached an intermediate or advanced level, but it’s also necessary to read a lot to be able to write Chinese properly. Reading also enables us to understand word usage and brings us closer to the culture behind the language. I’ll now let Sara talk about her approach and experiences of reading in Chinese. Enjoy!

I’ve been studying Chinese for 2-3 years. During that time, I’ve made my share of mistakes and stumbles, and I’ve done a lot of trial and error to discover the most effective studying methods. Here, I present how I read continuous texts in Chinese. such as books, comics, the lease to my apartment, newspaper articles, etc. I will go over the steps that I use, how I modify my steps for different situations, how I benchmark, and other issues. I am not suggesting that my approach is the best or ideal for every learner – rather, my intent is to give fellow learners ideas about how to develop their own approach to reading Chinese.

- Read the text, or a portion of the text, once cold. No notes, no looking up things up in reference books, just trying to enjoy it.

- Read the text or that portion of the text again. This time I make notes of any vocabulary or anything else that I want to look up in a reference, but I do not actually look at references until I are done reading the text. I like to make the notes right in the text itself so that when I actually open my references later, I can see exactly what the context for that word or phrase is. If one does not want to mark the text itself (perhaps it’s a borrowed copy) one can make the notes on a separate piece of paper.

- After the second reading, I look up whatever I marked. Nowadays I turn my notes into cards for Anki without fleshing them out on paper, but in the past I would write out the full explanations on paper.

- Now read the text for a third time. When using paper notes, I did this as soon as I have finished looking everything up in references and completing the notes. Using Anki, I wait until I have reviewed the cards for a few cycles before re-reading the text.

The Approach

This full approach was very helpful to me when I was at an intermediate level. At that time, I felt I needed to re-read the texts to help the new language stick in my brain – and I advise all beginner and intermediate learners to re-read texts. Re-reading texts is also helpful for advanced learners. However my time is not unlimited, so usually I think reading fresh text is a better use of my time so I can see words being used in many different contexts. I still use this approach – I just take out steps. For example, I often do the following –

- Read the text cold and mark anything I don’t understand or am uncertain about.

- Later go through my markings, take note of the context, look things up in references, and turn them into Anki cards.

Notice that in this shortened version I am only reading the full text once (I of course re-read the bits I marked).

One of my basic principles is to never interrupt reading to look things up. I want to get involved in the text, and having to pull out a dictionary every time I see a word I don’t know breaks the flow. Once in a while, if there is a word that is showing up over and over again, is clearly very important, and I have no idea what it means, I might pull out the dictionary in the middle of reading, but that rarely happens.

Which steps?

Of course, I decide which of the above steps to include based on why I am reading a text. Here are the most common situations:

- On a Break: Sometimes I want to focus on skills other than reading, or I just want to take a break from difficult texts. So I pick texts which I find enjoyable and relatively easy. I just read the texts once cold, without markings – putting in any more effort would defeat the purpose of taking a break.

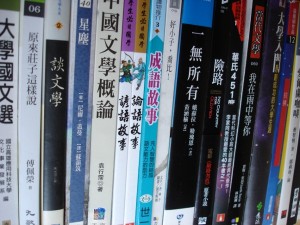

- Casual: These would also be texts which I am mainly reading for enjoyment, not expanding my Chinese – but if I do not consider myself ‘on break’ I will still mark whatever I don’t know, look up things in references, and make Anki cards out of them. The bulk of my reading practice these days is like this – it has to be enjoyable and not excessively difficult for me to be able to put in the many hours it takes to become truly comfortable reading Chinese.

- Pushing my level: This is when I am picking a difficult text so I can increase my Chinese proficiency (though I always pick a text which I am also interested in for its own sake – there are too many interesting things to read in Chinese for me to waste my time on a text I don’t care about). I am far more likely to add steps when the main purpose is to expand my Chinese – and if I feel overwhelmed, I will do the full approach described above.

- Specific purpose, example 1: I plan to write an essay about a text in Chinese. I will probably make the markings and Anki cards and re-read the text at least once (after a few rounds of reviews on Anki), even if it’s not challenging.

- Specific purpose, example 2: I have a prescription for some medicine, and the English instructions are so badly written that they are unreliable (this really happened to me). Even if I am 95% sure of what the Chinese instructions say, I would probably put in extra effort to be absolutely certain that I understand what my prescription says (such as talking with a fluent Chinese speaker to check my comprehension)

There are many other situations where something other than language acquisition goals might affect the way someone approaches a text.

Benchmarking reading comprehension

I like to benchmark two different things when reading Chinese; reading speed, and vocabulary comprehension (see this article for more about benchmarking language skills).

To benchmark reading speed, I need a set of texts which have equivalent length and difficulty, preferably of a type which I have also read in my native language (English). Thus, when I compare the speed I take to reach each text, I am comparing apples to apples, and I can also compare to my English reading speed. The set of texts I use is a manhwa called Goong (我的野蠻王妃 ). Each volume is of a similar length and has similar language, and a new Chinese-language volume gets published once in a while. I had actually been reading Goong in English before I started studying Chinese, so I know how long it takes to read a volume in English – but this is a personal choice.

Unfortunately, no two texts are completely equivalent, and many factors can interfere with the accuracy of the measurement. Each learner should find their own texts which personally works for them. Aside from comics, other good sources of long series of texts with consistent length and difficulty include: novels (each chapter can be counted as a separate text), series of novels, newspapers, magazines,, and blogs (if it is a very consistent blog). Olle Linge says that he uses the novel The War of the Worlds and reads it 10 pages at a time. If you have any other ideas about good series of texts to use for benchmarking, please comment.

I find it very encouraging when I know that I am encountering fewer and fewer unfamiliar vocabulary, so I benchmark it. Like benchmarking for speed, I need a set of texts with equivalent length and language difficulty. When I took paper notes, it was obvious when the notes were becoming fewer and fewer for each chunk of text. Now that I use Anki instead of paper notes, I use a different tag for every chunk. For example, I read an 8-volume edition of The Giant Eagle and Its Companion (神鵰俠侶 ). I used different tag for each volume. I could have also chosen to make tags for each chapter, or for every 20 pages. By tagging each equivalent chunk of text, I can track whether I have to look up more or fewer things per chunk. For example, according to Anki, theses are the cards I made for each volume of The Giant Eagle and Its Companion:

- Volume 1: 105 cards

- Volume 2: 74 cards

- Volume 3: 80 cards

- Volume 4: 92 cards

- Volume 5: 74 cards

- Volume 6: 60 cards

- Volume 7: 60 cards

- Volume 8: 73 cards

Now, notice that sometimes I had to look up more words than for the previous volume. Yet I had to look up 88 words per volume on average for the first half of the novel, but only 72 words per volume on average for the second half of the novel. If you’re wondering why I looked up so few words, it’s because this is the sequel to The Eagle-Shooting Heroes (射鵰英雄傳), which I read first. For the just first chapter of The Eagle-Shooting Heroes, I had to look up 82 words.

Sometimes there is a major vocabulary spike for a certain chunk. For example, if a story which mostly takes place on land has a scene which takes place at sea, I might have to look up a lot of vocabulary related to seafaring, and which would cause a vocabulary spike. But the overall long-term trend is downward. Measuring and seeing the downward trend is very satisfying.

Dealing with the glossing problem

When I read in my native language (English), particularly when I’m a little tired, I have a lot on my mind, or I am reading for a long period of time, I have a tendency to let things the words enter and exit my mind before I register them. For a long time, this was not an issue in Chinese because a) I did not have the stamina to read Chinese for long periods of time without break b) I read Chinese extremely slowly and c) reading Chinese required a lot of my mental faculties. However, I can now read Chinese for hours non-stop, my reading speed in Chinese has increased greatly (at least for works of fiction), I stumble on far fewer unknown characters/words/idioms, and it requires less of my mental faculties. So, if I’m not careful, I can read 10 pages of Chinese text and have none of it sink in.

In a way, it is a wonderful problem to have – it means that my Chinese reading skills are approaching my English reading skills. However, it is still a problem. What I do is that after each page or so, I try to summarize in my mind what happened. If I can’t make a summary, then I know that I need to be more focused, and I might even make myself re-read the page. This almost always slows me down, which is frustrating, but it’s better to read slower and absorb it than to fly through it. If I get involved in the story, I’ll stop doing the mental summaries because it is no longer necessary.

If you have any other suggestions on how to deal with the glossing problem, please comment.

The most important thing

The most important thing is to find a text that you are really motivated to read.

There is a comic – Evyione: Ocean Fantasy – which I loved when I first read it, but was never continued in English. Then I discovered that it had been translated into Chinese as 人魚戀人 – and that the Chinese-language edition went beyond where the English-language edition stopped. Even though the Chinese was significantly above my level, I was a lot more interested in reading it that whatever I was reading at the time in Chinese. So I dropped my short-term study goals had a kamikaze experience. It was the most challenging experience I ever had reading Chinese. I developed the approach described in this article so that I could handle Evyione (some refinements came later, of course).

And it was so worth it. I went from frequently feeling discouraged when I saw written Chinese to seeing any text in Chinese – no matter how difficult – as something I could handle if I had enough time and put in the effort.

If you cannot find any text for which you have a strong motivation, do some research on Chinese-language literature and pop culture. Particularly pop culture – I am amazed at how ignorant I used to be of Chinese-language pop culture. and I think most Chinese language courses do not do enough to introduce students to the pop culture. There was a time when there seemed to be nothing I really wanted to read in Chinese; now it seems like I’ll never have enough time to read all of the things I want to read in Chinese (many of which are not available in English). Do whatever you need to do to get a Chinese-language text that you are really motivated to read in your hands.

If you want to learn more about Chinese-language pop culture, you could follow my new column, It Came From the Sinosphere, at Manga Bookshelf, where I write about Chinese-langauge pop culture every week. There is also my article on reading comics in Chiense, which will be published here on Hacking Chinese in roughly a week..

Your own approach

I have shaped my approach based on my goals, my learning style, and the texts I am dealing with. These factors are obviously going to be different for every Chinese learner. My purpose in writing this article was to explain my approach to reading Chinese so that other Chinese learners could get ideas of things they could try to integrate into their own approach to reading. For example, I wish somebody gave me the idea of extracting vocabulary to make Anki cards earlier so I would have quit making paper notes sooner.

On the other hand, I think there might be situations where paper notes are more appropriate than Anki (for example, if somebody needs to have a good comprehension of a text within two days and has limited computer access during that period of time), so maybe somebody out there finds the idea useful. So rather than a prescription, I think of this as a series of ideas laid out on a table for anybody to take – some of them are not going to be useful for a particular learner, but there might be a helpful new thought or two.

My own reading approach continues to evolve as my goals, my Chinese proficiency, and the texts I’m working with change – so please comment about how you approach reading Chinese. I would appreciate some helpful new thoughts myself.

About Sara K

Sara K. has been studying Mandarin since Fall 2009. She currently lives in Taoyuan County, Taiwan, but grew up in San Francisco, California. She writes It Came From the Sinosphere for Manga Bookshelf, and has her own personal blog, The Notes Which Do Not Fit.

16 comments

Thanks for the article. I’m stuck at the low intermediate stage where the only reading I can do is textbooks and skyping in Chinese. I also do not have the luxury of living in a Chinese environment. I feel like there is some monumental jump from learner’s materials into native materials. I’m not sure what to do. I basically haven’t progressed much even though I’ve been studying Chinese as long as you have.

Oh yes, I remember the feeling of being a lower intermediate too 😉 It seems like there is a wide river between learner materials and native materials, and there is no bridge. For me, even though it was not as convenient as a bridge, I did manage to use comic books as stepping stones across that river. I’ve written an entire article about comics in Chinese, which should be available here at Hacking Chinese on July 18th IIRC.

A writer you may want to consider is Gu Long. I only started reading Gu Long when I was already at an advanced level, but I know some people use his novels to cross the river from intermediate to advanced. The paragraphs are usually only one sentence long each, and the grammar is relatively simple. I think his works are very appropriate for upper-intermediates, and I think even lower-intermediates can try his works if they are willing to be patient (see Olle Linge’s articles about kamikaze style study).

Since Gu Long is one of the most popular Chinese-language writers of the 20th century, his works should not be hard to find, even outside of Asia – inquire at your local library (even if they don’t have Gu Long’s works, they should be able to get them through inter-library loan).

Since you’re a lower-intermediate, the best Gu Long novel for you might be 蕭十一郎 (The Eleventh Son) because it is the only novel which has been translated into English, so if you get stuck you could refer to the English translation.

Hi Sara,

Thanks! It is inspirationnal.

I am studying chinese by myself and would like to find mangas in simplified chinese. My level is between beginner and intermediate, but my grammar is poor. I looked a lot on Internet to find references but most mangas seems to be in traditionnal caracters. If you have time, could you suggest a Web site or specific mangas that would be helpful?

Thanks again.

I am copying the response I put at my own blog:

As someone who (currently) only reads traditional characters, I am not an expert on what’s available in simplified. Nonetheless, I know there are children’s manga which are available in simplified characters, including the extremely popular 哆啦A梦. You can get all 45 volumes of it in simplified characters at this site:

http://product.dangdang.com/product.aspx?product_id=20645820

If you want a cheaper option, you can explore this website with webcomics in simplified characters. There might be something there which might be suitable for you.

http://comic.zongheng.com/

Thank you very much Sara. I will explore the second suggestion. Have a nice day.

Hi Sara. Thanks for your insights, most of which I agree with. However, I am slightly concerned by one small aspect of the blog. At the risk of sounding a touch cynical, unless one is rooted to a pair of manacles on Wangfujing with a Jinmao-sized tower of text books flanking one side and a similarly large mountain of Red Bull cans boxing one in on the other (not to mention matchsticks forcing one’s eyes to remain permanently wide open and a man with a large whip looming large in the background), I can’t for the life of me see how it’s possible to go from total ignorance to reading complex Chinese novels with the carefree ease of a native in ‘two-to-three years’ – technique, or no technique.

Though I appreciate I probably sound very snarky, the reason I making the point isn’t to snipe or be willfully sarcastic. Rather it is born of a concern that implying it is possible to spend two to three years learning Chinese (as a non-native adult learner) and emerging at a point where your native reading skills and Chinese skills are much-of-a-muchness is, to my mind, only likely to discourage those – like myself, perhaps – who have spent a good deal more time than that studying and yet continue to find reading in Chinese a real challenge. Even if one is lucky enough to be residing in a Chinese-speaking part of the world, have the freedom to spend every waking hour learning Chinese, and have the pedagogical insights to make full use of this labour, I don’t think many people could realistically achieve such a feat. If you have scaled these heights in such a short time, good on you; your insights are certainly of value. However, maybe a bit more disclosure on language background, or at least more detail on learning circumstances, is required to stave off festering resentments among the long-suffering, hard-working, Chinese-learning souls out here in the ether. Though it’s always dangerous to second guess a stranger’s circumstances (not least one I have never before personally met!), I suppose the blog would make much more sense if, for example, you had some kind of background in Chinese prior to formal study, or, say, you are a native Spanish speaker and thus your English is perhaps not absolutely perfect – making achieving parity between Chinese and English much more likely. Your excellent written expression suggests the second scenario is probably not the case!

Apologies for concentrating to intently on one small aspect of the blog. As I said, there’s lots to take away from this. Many thanks for sharing.

I’m not trying to respond to this in Sara’s place or anything, I hope she will give her own answer, but I want to point out that I went from zero to being able to read novels in about three years (whereof one was very far from immersion). Sure, I needed a dictionary, and sure, I didn’t understand everything. Was it enjoyable? Yes! Was it done with the ease of a native speaker? No! Reading novels is definitely possible, reading novels with the ease of an educated native speaker is perhaps not impossible, but very, very, very hard. I’m not trying to say that people who can’t read novels after three years are stupid, but I am saying that it’s definitely possible. It should be possible considerably faster than I did it, too.

Fair enough. Perhaps this hinges on different interpretations of both what Sara said and what it means to ‘read’ a novel. Being prepared to pick up a Chinese book densely packed with margin-to-margin characters is one thing (and not a small thing, I will freely concede). However, ‘reading’ it – as opposed to ‘deciphering’ or ‘studying’ it – is something different, I’d argue.

I think the line which raised eyebrows was the assertion that Sara had reached a point where “my Chinese reading skills are approaching my English reading skills”. I think a reasonable reading of that sentence would be to infer that Sara’s English and Chinese reading skills are becoming roughly equivalent in strength (though I appreciate there is an alternatively reading where the word ‘approach’ means merely that the gap is being closed somehow, even if the two competencies are still very unequal). If Sara really did mean that, then, yes, I feel justified in being a tad dispirited. For my part, I am able to make my way through modern Chinese novels and newspaper articles (and make sense of the odd Weibo posting – though this is probably the most difficult task of all), but it is still a slow process and demands far more mental strength than doing the same in English. Yes, in some ways, getting this far was a battle of confidence as well as linguistic ability, and perhaps I was slow to pick up confidence. But I couldn’t possibly suggest my Chinese reading level is anywhere near my English level. Moreover, no matter how many hours I put in, or where in the world I move to, I guess this will always be the case.

Question regarding your counting methodology of words you look up. If you do not recognize either character in a pairing, would you count that as 1 or 2? How about if you recognize both characters, but have never encountered them as a pairing, and thus are unsure of the actual meaning of the word? Would that be a 1, 2, or 0?

Sorry for the late reply.

I consider characters separate from words. If I do not recognize either character, I would count it as 3 (character + character + word) UNLESS it is a set of characters which are only used in that one pairing, in which case it only gets counted as one. How do I know whether those characters are generally only used in that one word? I check dictionaries.

If I recognize both characters, but not the pairing, that only counts as one.

Hi Olle, (or fellow commenters), I was wondering if you had any wisdom on the Defrancis Readers? I’ve been using the Beginning one for a few weeks now. It’s fantastically efficient in that every lesson only uses characters that have been introduced previously, adding about 8 more each lesson. The main downsides are that the content is kinda boring, and hard to get a feel for what’s being said. It’s a real long haul, and the expressions are from 50 years ago that I don’t find too much of in my spoken studies. The whole series up to Advanced is about 3000 pages of 100% progressive Chinese. I’m reading such magnitude without having to stop to use a dictionary because every word’s definition is provided. It’s had a huge impact phisiologically. It used to be strenuous to even read characters I was famailiar with, and finding them in a page felt like playing Where’s Wally, but I’m much faster at that know. If you haven’t seen them, I made a PDF of part 1 that I can show you if you’d like to investigate it.

Carry on .. Good work. Appreciated