Even people who haven’t studied Mandarin knows that it can take some time to learn the tones and some of the trickier sounds, but there are actually other problems you need to be aware of when it comes to pronunciation that are unrelated to the sounds themselves.

Even people who haven’t studied Mandarin knows that it can take some time to learn the tones and some of the trickier sounds, but there are actually other problems you need to be aware of when it comes to pronunciation that are unrelated to the sounds themselves.

The main problem is that most people will not give you honest feedback on your pronunciation. Most people who say that your pronunciation is great mean it as encouragement, not as a statement of fact, or if they do mean it, they are comparing you to other foreigners whose Mandarin probably isn’t very good. The fact that your teacher stopped correcting your tones doesn’t mean much either, as most teachers don’t have the time or persistence to keep working on pronunciation after the initial stages of a beginner course.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many other platforms!

How to figure out how good your pronunciation is

This means that it can be surprisingly hard to figure out how good your pronunciation is, and the likelihood is that it’s worse than you think it is. If you want to improve your pronunciation, it’s essential to identify what problems you have and start working on them as soon as possible. Some problems might go away naturally with more listening and more practice, but problems you aren’t aware of can persist and become so cemented they’re almost impossible to get rid of.

So what’s the solution?

You can do one of two things:

- Use the method I will introduce and explain in this article. If used correctly, it will give you brutally honest feedback on your initials, finals and tones. It’s completely free to use, but you do need a native speaker to help you out. It doen’t need to be a teacher, just someone who’s willing to help you out for half an our. With this method, they will not be able to be nice to you and make you believe that your pronunciation is better than it actually is. The method works for both listening (distinguishing and identify sounds) and speaking (your own pronunciation).

- Hire a professional teacher you can trust to not cuddle you. This is something I’ve worked with a lot and detailed feedback on every aspect of your pronunciation is an option add-on to my pronunciation course. The course itself covers everything you need to know about Mandarin pronunciation, but you can also choose to let me analyse your pronunciation and let you know exactly what you’re good at already and where you need to improve. You can read more about my pronunciation course here: Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence.

A smart method to discover problems with Mandarin sounds and tones

The method I want to introduce is a variant of what it sometimes called “minimal pairs bingo”, which probably doesn’t tell you much unless you’re a language teacher. In phonology, a minimal pair consists of two words that only differ in one single regard, such as “bat” and “bet” in English, which are the same save for the vowel sound in the middle. In Mandarin, the words 好 hǎo “good” and 老 lǎo “old” form a minimal pair because they only differ in the initial sound.

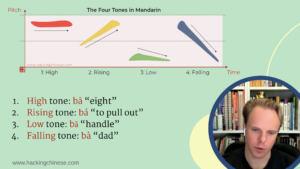

This difference between the words can be any phonological element, including tones, so 买 (買) mǎi, “to buy”, and 卖 (賣) mài, “to sell”, form a minimal pair. Naturally, we don’t have to limit this to pairs, so triplets or quadruplets are possible as well (larger groups are sometimes called minimal sets). You have probably seen at least one of these when first introduced to tones. Here’s the one I use in the pronunciation course:

High tone: 八 bā “eight”

High tone: 八 bā “eight”- Rising tone: 拔 bá “to pull out”

- Low tone: 把 bǎ “handle”

- Falling tone: 爸 bà “dad”

In fact, this method can be expanded to include 20 words at once, even if this is overkill for most people! I will show you why and how to do this later.

Here are the two main things you can use this method for:

- Diagnose your pronunciation and find out how good your initials, finals and tones really are

- Diagnose your sound perception and see how well you can identify initials, finals and tones

How to diagnose your pronunciation and perception of Mandarin sounds and tones

To do this, you need a native speaker and a way of writing down things so the other person can’t see what you’re writing.

Do the following:

- List a number of sounds you find difficult to distinguish. They should be as close as possible, so pick syllables or words that you find difficult to hear or where other people struggle to understand you. If you want to check basic, single-syllable tones, you can choose the four words listed above! Like I’ve argued elsewhere, though, you should move on to tone pairs as soon as you can. I will use tones as examples in this article, but will show you how to expand to initials and finals towards the end.

- Put them in a list or table to make them easy to point to. This should be done in a way that allows both of you to see the words. If you’re doing this with tones, you can use the tables I provide below (I’ll introduce them later).

- Tell your friend to write down the words in jumbled order, with each word appearing twice. If you use the list above with ba, your friend might write: bá, bǎ, bà, bá, bā, bǎ, bā, bà. It’s important that you don’t see this list!

- Tell your friend to say the words on the list in the order she wrote them, while you write down which word you think she’s saying. Repeating the same syllable a several times for clarification is okay. If you want a more casual version, you can just point to the right word and skip the writing, but I suggest you actually write down the answer to make it absolutely sure that they’re not cheating to make you feel better.

- Compare your list with your friends list. Obviously, if your listening is up to par, the lists will be identical. If you misheard something, this should be immediately obvious. This might not mean that you’ve definitively found a problem you need to work on, but it’s the first clue to suggest that there might be an issue there. Repeating the above steps with different syllables will let you know if you actually have a problem or not. Repeating with different native speakers is also a good idea.

- Reverse the roles so you are the one saying the words. By writing down the words in advance and asking your friend to write down the answers, you guarantee that no cheating is possible. If your friend writes down the wrong words, you know you have a problem. Please note that many native speakers prefer characters here, so it might be a good idea to include them.

How good are your tones and tone pairs really?

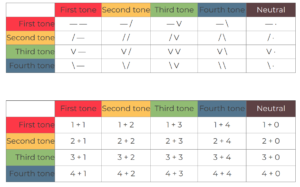

Below, I have included two tables containing all possible tone pairs in Mandarin, twenty in total, including the neutral tone. While you can use the full table to check your tone pairs, I suggest that you limit yourself to certain rows or columns first. The first time I used this method to check students’ pronunciation in class, I vastly underestimated how hard it would be and most students performed so badly that I deeply regretted using tho whole table at once.

| First tone | Second tone | Third tone | Fourth tone | Neutral | |

| First tone | — — | — / | — V | — \ | — · |

| Second tone | / — | / / | / V | / \ | / · |

| Third tone | V — | V / | V V | V \ | V · |

| Fourth tone | \ — | \ / | \ V | \ \ | \ · |

Or with numbers if you prefer:

| First tone | Second tone | Third tone | Fourth tone | Neutral | |

| First tone | 1 + 1 | 1 + 2 | 1 + 3 | 1 + 4 | 1 + 0 |

| Second tone | 2 + 1 | 2 + 2 | 2 + 3 | 2 + 4 | 2 + 0 |

| Third tone | 3 + 1 | 3 + 2 | 3 + 3 | 3 + 4 | 3 + 0 |

| Fourth tone | 4 + 1 | 4 + 2 | 4 + 3 | 4 + 4 | 4 + 0 |

This is a simple way of representing all the combinations of two syllables in Chinese. First look at the column to the left and select a tone, then combine it with any of the five available tones that can follow it. Please note that 2+3 and 3+3 are practically the same because a third tone followed by another third tone changes into a rising tone.

Here comes the crucial bit: You have to use words that only differ in tone! If you can’t find such words (which is highly likely if you use at least a full column or row), you need to make words up. You should not use words that exist in Mandarin but differ in more than one regard! For example, if your working on the first column above, you shouldn’t use the words:

- 飞机 fēijī “airplane”

- 明天 míngtiān “tomorrow”

- 老师 lǎoshī “teacher”

- 唱歌 chànggē “sing”

The reason is that the listener will be able to guess the right word regardless of tones. This is true even if you just ask people to write down what you’re saying in general, simply because they know that there’s only one common word with those syllables. For example, if you say féijí instead of fēijī, your friend will immediately think of an airplane because there’s really no good alternative.

Here’s how you can compensate by making something up:

- Use a single syllable in Mandarin (such as ba). Your tone pairs then become bābā, bábā, bǎbā, bàbā and so on. Most of these don’t mean anything, but that’s the point.

- Use a voiced sound without meaning (such as “mm”). This won’t make the listener think of any word in particular and might be less distracting. You’d be saying things like mḿmḿ and the like. Pure vowels also work, so ǎaāa.

- Use a word in your native language (such as “Paris”), then apply the tones to that word. This will obviously make no sense in Mandarin, but with clear tones, your friend should still be able to guess. Try saying Pārīs, Pǎrīs, etc..

Please note that this can take a little bit of getting used to even for a native speaker, but that it really does work. At first, it feels a bit weird to say bǎbā because it does’t mean anything, but that’s okay. Work your way through the jumbled lists and read each tone combination using nonsense words.

I have tried this with several different native speakers and it’s perfectly possible to get a 100% score even when using all 20 tone pairs using all three variants above! It’s not easy, though, and like I said, you probably should start with only one column or one row, then take the next one and so on, until you can expand to more thane one at once.

Get the most out of the feedback you receive

You can use more than just the answer to figure out how good your pronunciation is. If your friend immediately points to the right word with confidence, it’s quite likely that your pronunciation is not just okay, but actually clear. If she instead hesitates and don’t look at all confident, it could just be a wild guess, so a right answer might not be worth much.

Similarly, when you listen, pay attention to how difficult you think it is to identify the sound or tone spoken. This is obviously easier than trying to read your friend’s reactions, and it should be immediately obvious if a specific pair causes you trouble. There’s no point at all in guess here, so if you don’t know the right answer, just note it down as wrong without guessing!

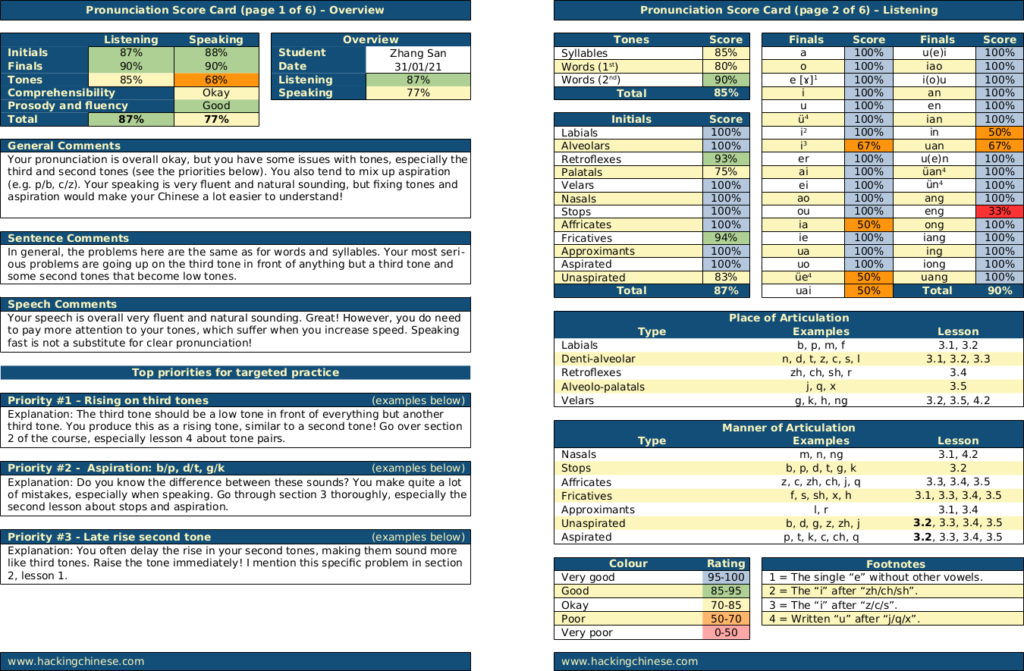

You can collect as much data about your pronunciation and perception as you want this way, then try to analyse what your biggest problems are and which areas are already quite good. This can be very simple, just noting that you got the third tone wrong a lot, or more serious where you add up numbers and check each combination carefully. If you want a really deep dive, I suggest you check out the version of the pronunciation course that includes feedback, as that contains more data than most students want. Here’s a sample of what the feedback looks like (the first two pages out of six in total):

Tone pairs to practise with

If you want to practise with real words, I have collected and sorted a very large number of HSK words based on their tones in the article below. You can find all words that have first tone plus first tone, third tone + fourth tone or whatever combination you want! This is excellent once you know what you need to practise so that you spend more time with words you have already learnt or that are useful to learn.

Focusing on tone pairs to improve your Mandarin pronunciation

Focusing on tone pairs to improve your Mandarin pronunciation

Wider usage beyond tones

In this article, I have used tones and tone pairs to show how to use minimal pairs (or triplets or whatever you fancy), but you can of course use it for any situation where words differ in only one regard. Here are a few examples:

- Aspiration: b-/p-, d-/t-, etc.

- Retroflex: z-/zh-, s-/sh- etc.

- Nasals: -in/-ing, -an/-ang

Any sounds that are close to each other in pronunciation can be used, which means you can do this in English as well. Here are some words if you want to torment your Chinese friends (these are usually really hard for them):

- World

- Word

- Whirl

- Were

Some limitations and caveats

There are some limitations to this method, though, so let’s discuss a few of them:

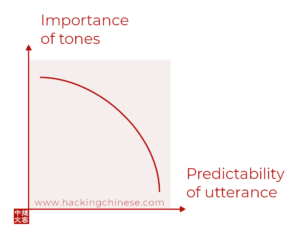

Context matters – When conversing in a language, context matters a lot. This means that you might feel that you can talk with people but still fail quite miserably at minimal pairs bingo. What does this tell you? Basically, it means that the Chinese you speak is understandable in the contexts you use it, but in spite of your pronunciation, not thanks to it. It could very well be that when your Chinese improves further and you start using it in less predictable contexts, people will find it much harder to understand what you’re saying. Pronunciation is for speaking what spelling is for writing: people can probably understand what you write even with bad spelling, but if you also have bad grammar and structure, people will struggle, and correctly spelt texts are much easier to read. I wrote more about context in this article: The importance of tones is inversely proportional to the predictability of what you say.

Context matters – When conversing in a language, context matters a lot. This means that you might feel that you can talk with people but still fail quite miserably at minimal pairs bingo. What does this tell you? Basically, it means that the Chinese you speak is understandable in the contexts you use it, but in spite of your pronunciation, not thanks to it. It could very well be that when your Chinese improves further and you start using it in less predictable contexts, people will find it much harder to understand what you’re saying. Pronunciation is for speaking what spelling is for writing: people can probably understand what you write even with bad spelling, but if you also have bad grammar and structure, people will struggle, and correctly spelt texts are much easier to read. I wrote more about context in this article: The importance of tones is inversely proportional to the predictability of what you say.- Limited scope – This method is a bit artificial and as we all know, saying a word in isolation when trying really hard to get it right is not the same thing as saying it in the middle of a conversation without thinking about it. This method is meant to help you spot errors, but it’s not the best method for practising once you know what your problems are. I suggest more listening and more mimicking to actually fix the problems. Once you know what they are, you should be able to pay more attention to them, hearing them more clearly when listening, which will gradually seep into your own pronunciation!

- Wrong but identifiable – This method works better for listening than it does for speaking. The reason is that your pronunciation might be understandable even if it’s wrong. For example, if you pronounce the fourth tone really loudly, very fast and with a ridiculously high starting point, your friend will probably still think that it’s a fourth tone, not because it’s a good fourth tone, but because there’s no good alternative. This means that this method works well for pronunciation in the sense that if your friend guesses the wrong word, you know you have a problem, but if they guess the right word, you can’t be sure if your pronunciation is okay or good. It sets a lower limit for how bad it is, though, which is still very useful.

Conclusion: A smart method for discovering problems with Chinese tones

I wish someone had introduced this method to me when I started studying Chinese, not after trying it out on my own after studying for two years. I’ve spent an enormous amount of time and energy to correct my pronunciation (especially the third tone; see this article) and if I would have known about my problems earlier, it would also have been a lot easier to correct them.

I used this method regularly to confirm that my pronunciation and tones are good. I’ve also used it when teaching to help students identify their own problems, which they often can.

What about you, have you tried something similar? What did you learn?

If you haven’t tried it yet, I really think you should!

Editor’s note: This article, originally from 2011, was rewritten (almost) from scratch in September 2021.

37 comments

Hello,

this is an excellent exercise! I will use it as soon as I can, including in reverse. Then maybe one day I will be able to consistently tell q from j…

I’ve been learning Chinese for years, both at school and in southern China, and to this day, I haven’t found one person capable of explaining how to actually pronounce tones (except for this nonsense pitch-level diagram which everyone seems to be copying around).

The most honest comment I’ve found was in a teacher’s manual, with instructions to “show it, but without too much explanation, as it may confuse the students”. I was wondering if you had come up with a theory on that problem.

Do you mean a theory on tone instruction in general or the last bit about the teacher’s manual? I think the tones can be quite easily and accurately described. The only problem is the third tone, but that is because textbooks make things too complicated. I believe that if you look at the third tone as an essentially low tone, most problems disappear.

I agree about the third tone. That’s what I’m teaching all my students and what I wrote in my book.

Very interesting idea, I shall try it! Thanks!

@Learning the third tone – Hacking Chinese

You hit on a key problem with non-native speakers and the problem with a third tone second tone pattern (like 美國). I hear the same problem with 場合 and a few others, where the third tone (initial tone) becomes second tone and the second tone becomes a third tone. Even if people know that the tones should be third second they still say it wrong.

I for one think this phenomenon needs more research… cause I want to know how to fix it!

I am currently doing research on third tone instruction. I think you might find this interesting: https://www.hackingchinese.com/?p=768

Is it just me or there is a problem with a picture/diagram? Thanks.

There is! The server crashed and I haven’t been able to restore everything. I’ll do my best to replace the diagram asap. Thanks for letting me know!

I have now recreated the picture. Let me know if you find anytihng else that isn’t working. Thanks again for pointing this out! 🙂

I see what you’re getting at here. I use this method for teaching English. I never thought about reversing it for self-study! Fortunately, Japanese doesn’t really have too many tones or phonemes that aren’t in English. But this is very good advise for Chinese students!

Don’t you think we Westerners obsess with correct tones? Yes, they’re important but not as important as getting your point across, i.e., communicating. Even native Chinese speakers don’t get their tones correct 100% of the time. I’d like to take a contrarian view: don’t obsess because sometimes the results may be better than what we intended. Well, at least funnier.

To put it very briefly, I think you’re wrong. I think most people obsess way too little about tones. Obviously, I don’t know your case or the people around you, so I can’t comment on your particular situation, but in general, I think people should pay more attention to tones, not less. If we look at different kinds of pronunciation problems, tone errors are the ones most likely to cause communication problems. I’ve written about tones in several other articles, checking them might perhaps explain the reasoning behind what I say:

Tones are more important than you think

The importance of tones is inversely proportional to the predictability of what you say

Of course, if your goal with learning Chinese is to sound funny, I don’t have much to add. 🙂

A problem I felt with learning Chinese is the emphasis on tones. Not in the sense covered by your article on why they are important, because I understand that I need to pronounce tones correctly. I’ve read a lot of sources on what tones are, how they are represented, and even saw an example where the third-tone could be thought of as a low tone. But, still, my tones are still horrible and I have no idea how to fix it other than hope that it will improve over time.

The problem I had was that it was a Chinese 101 college class, and yet I could almost never be able to read aloud or speak a full sentence because the instructor kept interrupting me and reiterate the same statements made before. I’ve made decent progress in learning other languages, but never have I made progress without being able to say a complete sentence regardless of its pronunciation.

I think that pronunciation improves over time, both naturally and coached. Perhaps I squandered my time by being irked by the constant interruptions when practicing. As important as tones are, I see it as a continuous progression and regression in the early learning phase if one is not in a native Chinese-speaking environment, and should be able to go to the backburner for a while.

For now, I have not come across instruction on tones that allows me to fully understand what it is I am doing wrong. The closest I have gotten is that, according to Stuart Jay Raj regarding Thai, tones are produced by constricting the throat for the high pitch and opening it for the low pitch. And even with this, I still have no idea if I am pronouncing my tones correctly. Perhaps I will figure it out whenever I finally get to visit China.

I used to feel this way and I kinda understand your point. Anyways, if you want to sound natural, you can’t really obsess over the tones as they are taught, as Chinese people don’t even speak that way.

However, in the past year I’ve tried to focus more on my tones and I think it has made me a more confident speaker. In the past, I could usually get my point across fine, but I think there is less confusion now since my pronunciation of tones is improving.

Hi – What do you think of “Speak Good Chinese” program to evaluate the accuracy of your spoken tones?

I found it through a comment on your site, actually.

I’ve used it a bit, but my level isn’t good enough for me to really judge its accuracy. Have you tested it out enough to evaluate? With yourself, with native speakers, etc?

I like the method you describe here, but the limitation is the patience of your native-speaker partner. If the program is a good judge, then it has the advantage of being both unbiased and truthful, plus never getting bored with you practicing for hours at a time 🙂

Sorry, didn’t include a link. The program is at:

http://speakgoodchinese.org/

Hi! Sorry, haven’t tried it, but I’m not very optimistic. Most of the software I’ve tried (and I’ve tried quite a lot) have been either useless or seriously flawed in some way. Perhaps it’s unfair of me to be so negative about something i haven’t tried, but I will change my mind only when i find something that actually. works. 🙂

Thanks.

I understand you. I tried 2 programs already which were hard to use and even at my beginner level pretty clearly flawed.

The “Speak Good Chinese” software program (praat), I found it from the long-ago comment on your site and downloaded it. I’ve played with it 30 minutes each evening this week. It’s free and simple to use, which is nice, and seems to work better than what I’d tried. I wasn’t sure about its evaluation of my pitches, though, which is why I asked.. I just hope that the guidance it’s giving me in saying my tones is right or I’ll have some bad habits within a few more days lol 🙂

I just want to point out that Praat isn’t a “Speak Good Chinese” software, it’s mainly designed for linguists to analyse pronunciation of different kinds. Praat isn’t a program I recommend using regularly unless you know what you’re doing. It’s fairly easy to make mistakes with settings and make the pitch look weird and so on. If you’re worried, find a native speaker to check if your tones are right or not. I use Praat a lot, but it takes some time to learn how to use it.

Very clever, Olle. This is a nice method because it builds the feature you need into the heart of the game, so you will get the honest feedback you want by necessity.

I know exactly what you meant in the context, but taken out of context I think you would disagree with your own words here: “Since native speakers tend to understand what people say even if they are pronouncing the tones incorrectly…” Might be worth clarifying that one!

Hi Olle,

Nice article. Now you have me thinking about how to develop software that will take care of all the tedious parts of this exercise which both the native speaker and the learner can set up on their devices and practice back and forth, keep track of progress, etc.

I struggle for years with correct pronunciation – tones.

Now Im in stage where 2 and 3 tone are off in specific combinations.

For example “xiang3” or “du2pin3” or “Chi3 zi5”.

I feel like I have tried everything and still cant get the tones right:-(

Most people and teachers the tell you to do the falling-rising tone but larynx is a complicated tool.

I never learned how to sing and I know my singing is terrible(they really do tell me to shut up).

Funny thing is, Olle, I just thought I have invented similar Exercise with my students the other day. I was about to check if there was any improvement in my tones but did not know why. So I figured I will disguise it as warmup quiz exercise in my classes. It turned out to have a great success as a warmup and a devastating impact on my self-confidence.

I am still on my quest for better tones. What I would love to have is a visual guide into pinyin pronunciation, showing what is happening with your tongue and larynx when speaking different tones.

Thank you for the idea!

Hi Olle!

I just discovered your website and I’ve been LOVING it. I’m learning so much, and I’ve signed up for the course. I’ve read maybe 30 articles so far, and it just occurred to me that I haven’t seen a single typo, which is remarkable! It occurred to me when I found a little one. Your site is so meticulously proofread that I thought you’d want to know!

In the “words to practise with” section:

“no (commonly used) word that is pronounced liket hat.”

Just trying to help you 0.01% as much as you’re helping me! Thanks!

Hi Emily,

Thank you! I’m sure there are plenty of typos as I check articles myself and don’t always have the time to be as careful as I should. I appreciate it when readers help me out and I have already fixed the issue you pointed out! I’m also happy to hear that you find the content interesting, of course. 🙂 Good luck!

Best wishes,

Olle

I use google translate and Papago to speak the chinese word that I am practicing. If the translation to english is correct, I know my pronunciation is close!