Ever since I started learning Chinese, I’ve heard people say that if I want to reach an advanced level, I should focus on 成语/成語 (chéngyǔ). They allegedly summarise the wisdom of the Chinese civilisation and carry the soul of its culture.

Ever since I started learning Chinese, I’ve heard people say that if I want to reach an advanced level, I should focus on 成语/成語 (chéngyǔ). They allegedly summarise the wisdom of the Chinese civilisation and carry the soul of its culture.

However, the role of chengyu in Chinese language education for foreigners has always irked me. For most students, these idioms are nowhere near as important to learn as they are made out to be, and the way chengyu is taught is deeply flawed.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode #194:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

In this article, I will share my own experience of learning and teaching chengyu. Are they a magic key to Chinese language and culture, or a waste of time?

Chengyu and other idiomatic expressions in Chinese

Chengyu are typically four-character idioms derived from classical literature. These fixed expressions often carry significance beyond the sum of the characters they are made of, so their meaning can be opaque, even if you have a good understanding of Chinese characters and know enough about literary Chinese to decode their internal structure.

To fully understand the idiom, you need to know its derivation. For example, the commonly used chengyu 自相矛盾 (zìxiāngmáodùn) means “paradoxical” or “self-contradiction”, but this is not apparent from the characters themselves, which means “self”, “mutual”, “spear” and “shield”.

The meaning “paradoxical” only makes sense if you know that the story behind this chengyu is that of a merchant selling spears and shields, claiming that his spears can pierce anything and his shields can withstand any attack. A clever bystander then asks what happens if you use one of his spears to try to pierce one of his shields.

Chengyu is only one type of Chinese idiom out of many. If you want to learn more about other types of idiomatic expressions, you can look up 俗语 (súyǔ), 歇后语 (xiēhòuyǔ) and谚语 (yànyǔ), but I rarely hear them touted as keys to all wonders, and students seem less obsessed about them, which is why I will focus on chengyu here.

My experience: Using chengyu to reach an advanced level

Let’s look at myself, a fairly typical example. As mentioned in the introduction, I heard that chengyu was the pinnacle of the Chinese language and encapsulated the wisdom of the ancients. I learnt numerous stories about them, such as the one about 自相矛盾 (zìxiāngmáodùn) related above. When I tried to use the chengyu with native speakers, they were overjoyed that a foreigner spoke such advanced Chinese.

The rumour was true; chengyu truly is the key to Chinese language and culture!

All this was wrong and nobody thought my Chinese was advanced

Then, after having learnt Chinese for many years, I realised that this was all an illusion. Most of the chengyu I learnt turned out to have limited usage (more about this later). When native speakers said it was cool that I used chengyu, it was in a “Oh, look, the foreigner is trying to use chengyu, how cute!” kind of way. Most of my attempts were also incorrect, but most people are too polite to say so.

To mention a concrete example, the textbook I used as a beginner in Sweden (汉语口语速成) had the chengyu 十全十美 (shíquánshíměi) in it, with the translation of “perfect”. I then proceeded to use this idiom incorrectly a few dozen times before I figured out that it’s mostly used in the negative, and if it is used in the positive, the standard is pretty high. It’s not something you say as a response to a question about going out for a beer.

Rethinking my approach to chengyu

I have now had more than a decade to think about the role of chengyu in Chinese language education for adult second language learners. In essence, I have three things to say:

- Chengyu is more limited than you think

- Always learn chengyu with a sentence

- You don’t actually need chengyu

1. Chengyu is more limited than you think

The first thing you should know about chengyu is that they typically express specific concepts. The usage is often much narrower than any English definitions you see in connection with the idiom. This isn’t true for all chengyu, some even have closely corresponding expressions in English (here are some examples), but it is true in most cases.

Let me tell you about a game I used to play when writing articles. I had a good passive grasp of chengyu, so when I wrote articles, I often knew that there probably was a chengyu that would fit in a particular sentence.

The game was like a boxing match: me vs. chengyu When I used an idiom correctly, I scored one point, and when I used an idiom incorrectly or awkwardly, my opponent scored one point.

I almost always lost, even after having studied Chinese for many years and focusing a lot on writing. Using chengyu correctly is hard. This is true for other words in Chinese as well, but it’s particularly tricky with these idioms.

Chengyu are harder to learn than most vocabulary

If we take normal words and experiment by expanding their use to areas in which we haven’t encountered them before, we will sometimes find that they work in this new context, and sometimes we’ll find that they don’t. Through a mix of negative and positive feedback, we slowly build an accurate mental model of how the words are used.

Making mistakes in Chinese is necessary to adjust your mental models

When you experiment with normal words, you’ll be right a fair number of times, but with chengyu, you will almost always be wrong.

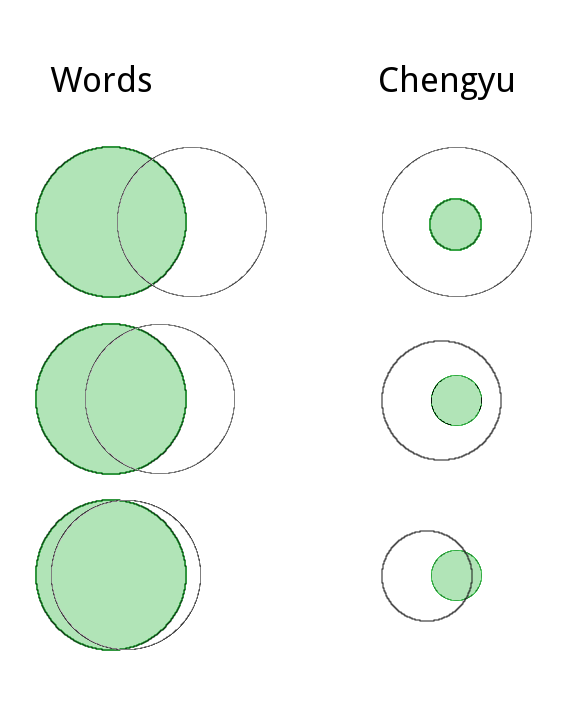

Here is a rough representation of what’s going on. The green circles represent correct usage and the white circles represent how learners tend to think about it. If the circles overlap completely, the word or phrase has been mastered.

As we can see, learning words is about adjusting the circles so they match (the size should vary too, but that would make the drawing messy). For chengyu, though, the most significant difference between the circles is the size. Chengyu usually has a much more narrow usage than learners think.

Figuring out how a chengyu is used, gradually without noticing it

Let’s look at an example. I don’t remember where I learnt 不知不觉 (bùzhībùjué), but it’s a very common chengyu. Most dictionaries define it as “unconsciously”, “unwittingly” or “without noticing”. With this mental model in your mind, you can spend years and never understand why it’s underlined in red whenever you use it in writing, and why people frown when you use it in conversations.

Until you realise that the usage is much more limited than you thought. 不知不觉 (bùzhībùjué) is typically only used to refer to the passing of time, that something happens or becomes true as time goes by, without you noticing. Once you know this, it becomes obvious, as almost all examples you encounter match this new model.

Acquiring that model takes an awful lot of input, though, or someone needs to point it out to you. This requires good and honest feedback, which is not easy to get.

How to get honest feedback to boost your Chinese speaking and writing

This brings me to the second point:

2. Always learn chengyu with a sentence

The biggest mistake students (including my past self) make is that they treat chengyu as normal words, which isn’t a good approach. Instead, learn each chengyu in a specific context. I don’t mean that you should just add an example sentence to your flashcard program, I mean that you should learn the example sentence and the chengyu as one unit.

Ideally, the sentence should show the way the chengyu is typically used. If you choose a random sentence you find online, it’s unlikely to fulfil this requirement.

Some chengyu are only used to describe one specific thing, so if you know that one sentence, you’ve covered most of the uses of that chengyu!

In other words, you should start from a tiny small circle and then slowly expand that as you find other examples of how that chengyu is used, rather than drawing a big circle and gradually shrinking it. This will mean that you use chengyu less, but you will also avoid using them incorrectly.

3. You don’t actually need chengyu

Chengyu are cool. I like the stories and the cultural and historical insights I gain through the stories. However, saying that you have to be able to use lots of chengyu to get good at Chinese is simply wrong.

Do you have to understand chengyu? At a somewhat advanced level, definitely.

Do you have to be able to use chengyu? Not really. It’s perfectly possible to speak Chinese extremely well without using many chengyu.

Chengyu are cool, but that’s not enough

Your normal vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation matter much more than if you throw in a chengyu here and there. And remember, if you throw one in the wrong idiom or use one incorrectly, you’ll show that you don’t know that much, and it certainly doesn’t make communication easier.

As a beginner, it’s cool to be the cute foreigner doing his best, but that’s not so cool when you’re trying to grow up in Chinese and become an adult student.

Naturally, if you’re Chinese is so good that it starts approaching an educated native speaker, you can ignore what I just said. You also can’t escape some common chengyu even at a lower level.

That’s not what I’m talking about here, I’m talking about the thousands of chengyu that pop up in books, blog posts and YouTube videos. Understand them, study them if you like, but do so because you’re interested and like it, not in a vain attempt to make your Chinese more advanced, because you will most likely shoot yourself in the foot.

Learn the most common chengyu first

If you don’t love chengyu, I suggest you learn the most common ones. The general rule is that if you hear a chengyu three times in different situations, it’s probably worth learning it. An alternative is to check this article by Carl Fordham, where he gathers 20 chengyu that are actually useful.

In addition, note that there is no direct relationship between how interesting a chengyu story is and how useful the chengyu is. People who write about chengyu for learners tend to focus on the chengyu that have the most interesting stories, not those that are most useful. Interesting stories are great for reading practice, though!

A question of efficiency

The real reason I think students should spend less time on chengyu is that the effort it takes to learn to use a chengyu is several times greater than that required to learn most ordinary words and phrases. Unless you already have a very broad vocabulary, it’s also likely that these ordinary words and phrases are more useful.

Thus, you get more value for your time and effort by focusing on high-frequency vocabulary. Some chengyu qualify as high-frequency vocabulary, so learn those and leave the rest for later.

I’m not saying that learning to use chengyu is a complete waste of time, nor that they lack cultural significance, but I am saying that you probably have more important things to learn. If you enjoy reading chengyu stories (in Chinese), then do so; it’s excellent reading practice, but don’t think that chengyu will unlock advanced Chinese.

Editor’s note: This article, originally published in 2013, was rewritten from scratch and massively updated in April, 2024.

32 comments

I am not Chinese, but I spent most of my formative years growing up in Taiwan and attending local schools (I went through High School and Medical College in Chinese). I took the same tests as my classmates and so on – just as any immigrant here would. When I returned to the U.S. I worked in a language capacity for the U.S. government for a time. I was rated as “near native” on both written and spoken exams by the Department of State and D.O.D.

My point? It is very important to understand Chengyu and their context, as well as what they imply and the color they bring to what is being said (or written). It is not important to be able to use them at all – in fact it might be seen as pretentious for a non-Chinese to use them more than very occasionally.

I return to Taiwan every year (I hope to retire there, it is “home” to me). I very seldom hear even well educated Chinese using any of the standard Chengyu – however, there are a slew of new slang equivalents, so one must always strive to keep up or look bewildered.

You bring up an excellent point I completely forgot to mention in the article. Using words that are too “fancy” might actually have adverse results. It’s one thing to throw them in and show people “hey, I’m a 認真 foreigner trying to learn your language”, but something else when you’re already at an advanced level. If you pepper your language with idioms and advanced phrases, people might instead think you’re trying to show off.

This is a very good article. Chengyu’s shouldn’t be used excessively and there’s a time and space for it. Like you said as long it’s in the right context, it’s alright. However there is one thing I would like to bring under attention. When I was learning chengyu’s, it struck me that it has a different linguistic structure as oppposed to idioms in the English language (or any European language Im concerned) which is a sentence on it’s own, whereas most chengyu’s cant exist on its own. My teacher told me it should be used as either a conjection or a stative verb/adjective (Eg 马马虎虎).

In addition, while you should be ergonomic with chengyu, I would encourage students to familiarise themselves with it instead, especially the 100 frequently chengyu (we had to learn this by heart, no joke) as they show up quite a lot in the media and its interesting if you are learning classical chinese as well.

Thank you for your comment! You are right that students need to pay attention to how chengyu fit into sentences. However, this is unique for each chengyu and even though you can find clues in the structure of the idiom, that usually require an extensive knowledge of the characters and the composition of chengyu in general. There are quite a lot of chengyu that can be used independently, actually. I think Baidu is probably the best place to look for information about this. For instance, this is the entry for 十全十美. Under 用法 it says 联合式;作谓语、宾语、定语、补语;含褒义。I don’t know of any dictionary that does this in English, if anyone else knows, please leave a comment!

Hey there, I am pretty sure 马马虎虎 is not a Chengyu. Its a Redoublication of a two-syllable adjectives to increase descriptive meaning. 马虎 → 马马虎虎. Like 漂亮 → 漂漂亮亮 or 安静 → 安安静静. I think for some reason its very rare that somebody actually says 马虎 but still it does not have the structure of a Chengyu, which you can usually recognize easily, because Chengyus are actually not 普通话, but 古文.

I think thats actully a very important point missing from the essay. If you really want to UNDERSTAND Chengyu and thereby make it much easier to remember and use them, you basically have to learn Classical Chinese. I think Chengyu mostly causes confusion, because people dont realize those idoms come from basically another language, many of them are quotations directly taken from Classical texts and use characters like ,所, 而, 之, 无 as grammatic particles like in classical Chinese. So my advice for everybody who wants a deeper understanding of Chengyu is getting the book: Outline of Classical Chinese Grammar by Edwin G. Pullyblank.

Re: is it worth learning chengyu (question in the newsletter)

Of course, I think learning lots of chengyu well enough to understand them in context is valuable, especially when reading literary Chinese, but that’s not what you discuss – namely, knowing them well enough to be able to put them in your output.

Learning chengyu well enough to use them is, in my opinion, only worth it if:

a) they are really common (i.e. 莫名其妙)

or

b) you have a specific purpose. For example, lately, I’ve been describing a lot of scenery, and it gets boring after a while if you just say everything is 漂亮. Obviously, there are other words which can describe scenic beauty which aren’t chengyu, but there happen to be a lot of scenery-specific chengyu, and when writing about spectacular scenery, using a chengyu or two really helps.

Hmmm. Maybe I work with a lot of pretentious people, but everyday in the office I hear chengyu said in conversation with people talking to me and with each other.

I agree that using them too often can make you sound pretentious, and that using them wrong can make you look stupid (the English proverb “better to be thought a fool than open one’s mouth and remove all doubt” comes to mind), but sometimes a chengyu is just perfect for what you want to express, but easier than saying it out in a sentence.

I don’t think there’s much difference between using chengyu and using proverbs in any language – if you walked around peppering your speech with proverbs in English people would think you were a bit strange, but sometimes you just need to use them. Of course you need to use them right, that’s obvious, but looking at the subject any deeper is just over-thinking it, in my opinion anyway.

Also, I’ve noticed people use a lot of chengyu, especially used independently, chatting on QQ, which often feels to me the equivalent of a casual conversation, but perhaps the act of writing hanzi makes people use more chengyu than they would in actual speech. Any thoughts on this?

@Sam:

Note that I didn’t say that you shouldn’t learn to understand these idioms, I’m just saying that it’s not efficient to try to learn how to use them (except for the most common ones, obviously). Regarding your last question, this isn’t based on actual research, but I think you’re right in saying that chengyu are much more widely used in written Chinese.

Chengyu are actually portrayed in movies as the typical Chinese pendantic scholar.

While I don’t take them too serious, I do have a couple of reference books for them.

These days, it seems the main use is for the fun or irony of using one. Taiwan’s traffic is notoriously dangerous, so saying “The road is like a tiger’s mouth.” via Chengyu will be a smile. Or running into a crowded event and mentioning “People mountain People sea”.

In other words, there is no payoff in being the pedantic scholar, Chinese or otherwise. But when people recognize your wit or irony, you have made a friend.

One can play with Chengyu and get people to laugh.

The only thing I would add (and you did touch on this) is that chengyu are actually used quite often in written materials, so for Chinese students who would like to get to a level where they can read Chinese literature, knowing a lot of chengyu is absolutely essential. It’s not uncommon to see a dozen chengyu on a page when reading stuff by Eileen Chang, Moyan, etc. Unfortunately, for those of us who aren’t looking to use a bunch of chengyu in our spoken Chinese for the sake of showing off, learning them is a pretty thankless endeavor because nobody will ever know that you actually know several hundred of them!

Thank you!!! I very seldom hear chengyu in everyday life. They are very interesting and can explain a lot about the Chinese mindset, but it’s really not worth trying to use them unless you are VERY certain of the correct usage – don’t experiment! If someone uses a chengyu I don’t understand, and it is a context in which I am free to ask, they are always quite happy to explain the meaning to me.

I had this conversation with a friend of mine from Tianjin over the weekend. (She accuses me of speaking like a member of the older generation – which is true, as I was heavily influenced by my adopted father, a very well educated man of the pre-WWII generation). My friend made the point that in conversation it is much more important to understand and use 歇後語, especially if one is talking politics or gossip (which is about 90% of modern Chinese conversation….)

Thank you for this interesting post about chinese 成语。I have been learning Chinese for a few years as well and somehow I just can’t memorize the countless 成语 that I already learned. I do agree about almost anything you said in your post, however I am asking myself how I can learn 成语 more efficiently. In terms of Chinese language learning, I am wondering if there are maybe some syntactical rules within cheng yu? I am talking about the position of characters within a chengyu and also about the semantics of a chinese character within a chengyu. For example, the character 之 is often used in cheng yu and as far as I noticed, it is often used in the “third position”. I know that it usually stands for 的 within a 成语. This kind of knowledge already helped me a lot to improve my understanding of 成语. Are there any other “hacks” for learning and remembering Chinese idioms? Would love to hear more about that!

Yes, there is a method to the madness. Chengyus are taken from Classical Chinese text and therefore their syntax and grammar follow the rules of Classical Chinese (古文,言文言). For example 之 zhi functions as a demonstrative pronoun (that) or object pronoun (it, him, her) in Classical Chinese most of the time.

For example: 必知乱之所自起,焉能治之。 You have to know where chaos originates from, than you can control IT there.

Here 之 is first used as a marker of nominalization for 乱 and in the second part it functions as a object pronoun。

Dont quote me on this, as my understanding of Classical Chinese Grammar is 马马虎虎 at best. ^^

It depens on what your aspirations are. 成语 are not necessary, if you just want to be functional in the language. However, if one has aspirations to become eloquent – here meaning to use exactly the right word/expression in a given context – then you will need to learn 成语。I also belive this to be the case, if you wanted to reach an academic level of language use.

I like to compare 成语 not just to proverbs (as proverbs in English are not used as frequently as 成语 are in Mandarin) but to idioms, clichés or borrowings from literature in English. For example, understanding/using the following example expressions would probably require a higher level of English (perhaps also a knowledge of British English) since you probably cannot guess what is meant without actually knowing the expression. It is the same with many 成语.

Go pear shaped

red herring

rock and a hard place

slop chit

cry wolf

catch 22

42

Pound of flesh

Make one’s bed and lie in it

and then of course sport analogies: sticky wicket, in the rough,on a par with etc

If you wanted to speak English at this level, you would have to make a proactive effort in learning such expressions. Also note that if a language learner’s level is not „eloquent”, some native speakers may employ a more basic vocabulary to converse with that person and hence the language learner will not get exposure of the “higher level” of the language.

But it all depends on your aspirations. I personally want to achieve this level of Mandarin and I find the effort I am putting in worth it.

I think the point is that 99.99% of all learners are very far from being either eloquent or educated in a native sense of those word and that, therefore, it matters little if you can use 成語 or not. What you say is true, it’s just not relevant for a huge majority of students. My problem with the way 成語 are taught is that they are treated as being really important from intermediate up, whereas in fact they become important so late that it’s not relevant for most students. Of course, it’s essential to understand 成語, but not how to use them.

“You don’t actually need chengyu; they aren’t magic keys to anything”

I can’t agree with this point. Chengyu are the essence of Chinese and they are extremely powerful tools. Chengyu only exist in the Chinese language, making it the most powerful language in the world.

Chengyu are the keys to higher level Chinese. In English if you don’t use idioms it’s totally ok. However in Chinese if you don’t use chengyu, you are lower than elementary school level.

Back to my senior high time, there was a university fair. I talked to a representative from Canada. He spoke really good Chinese. When I asked about2 things which was better. He said “各有千秋吧”. This really impressed me. A very appropriate usage of chengyu and modal particle. Not all Chinese can think of this chengyu in this situation!

This is a very helpful post, thank you.

Do you have any list or link tipps for 歇後語, too?

Thanks for your timely article. I have ignored chengyu for a long time because I was not yet at an advanced level. However I have now started collecting and researching the most common ones for two reasons.

I work in the media industry so I’m aiming to read media articles. Based on my reading and my friends’ reading, we find longer news articles and magazine articles use chengyu. Often they seem obscure because they describe a very rare, news worthy occurrence but I started collecting them to see if they pop up again.

Recently I have been preparing for the HSK 5 exam. The reading section is very difficult to finish within the time limits. Although I’ve learnt all the standard vocabulary, my teacher and I found that it was mainly chengyu that were confusing me as I tried to read the stories quickly. She suggested I read through common chengyu so at least I can recognize them.

So I started looking for common chengyu. My teacher recommended Baidu to look up ones I didn’t understand. I also really like the usage tips but I’m lazy and it’s hard to read quickly. I found Gene Fordham’s list. There are a couple of the “top 50” chengyu on memrise etc. But I found it hard to go further.

My latest find is Routledge 500 Chinese Idioms by Liwei Jiao. The English explanations are a bit simple but it’s got good examples. It is good for beginners as it has pinyin, and can even be read by people who are just interested in the cultural meanings. It’s based on things like Chinese high school textbooks as well as academic texts so I’m confident the first 200 might be useful. I’ll let you know if I get to 500!

Haha, thats funny, I just started going through the exact same book 2 weeks ago, tackling it one Chengyu per day. Its definitely one of the better Chengyu dictonaries out there.

That book contains 500 suyu, not chengyu.