Even if most students don’t come into contact with research into language learning directly, some still do so indirectly through newspapers, online blogs or social media (I share interesting articles and reports on Twitter, for instance). Research is sometimes also featured in mainstream newspapers and tend to generate a lot of buzz (see this article about a “new” approach to learning characters). This leads to tons of questions from people who generally don’t ask questions and it also generates online discussions. This is good.

There is a problem, though. It strikes me that many people don’t really know what to make of research results. Some overestimate the importance of research, others don’t care about research at all. Does science matter? Is research into language learning scientific? What (if anything) can science tell us about learning Chinese? Let’s look at the main problem with mainstream reporting of scientific findings.

What you read in second-hand, popular media is often exaggerated

What you read in second-hand, popular media is often exaggerated

The first thing you have to understand about news coverage of any kind of research into learning and/or languages is that journalists sometimes tend to exaggerate. Researchers themselves are usually more conscientious and well aware that their findings might be limited to a certain group with specific characteristics. There is usually a section in a scientific report where the researchers themselves criticise their own research, but that is often omitted in second hand sources.

Sometimes journalists focus on the wrong part of the experiment or wilfully misinterpret the results (this shouldn’t be very common, though). Their primary goal is to make people read their articles and of course they do so partly by educating people, but there are many shortcuts. I don’t mean to say that all journalists only care about how many people read the article and that the profession in general lacks morals, I’m just saying that I’ve seen quite a few examples of this and that, in general, you shouldn’t assume that your own edification is the main goal of the articles you read.

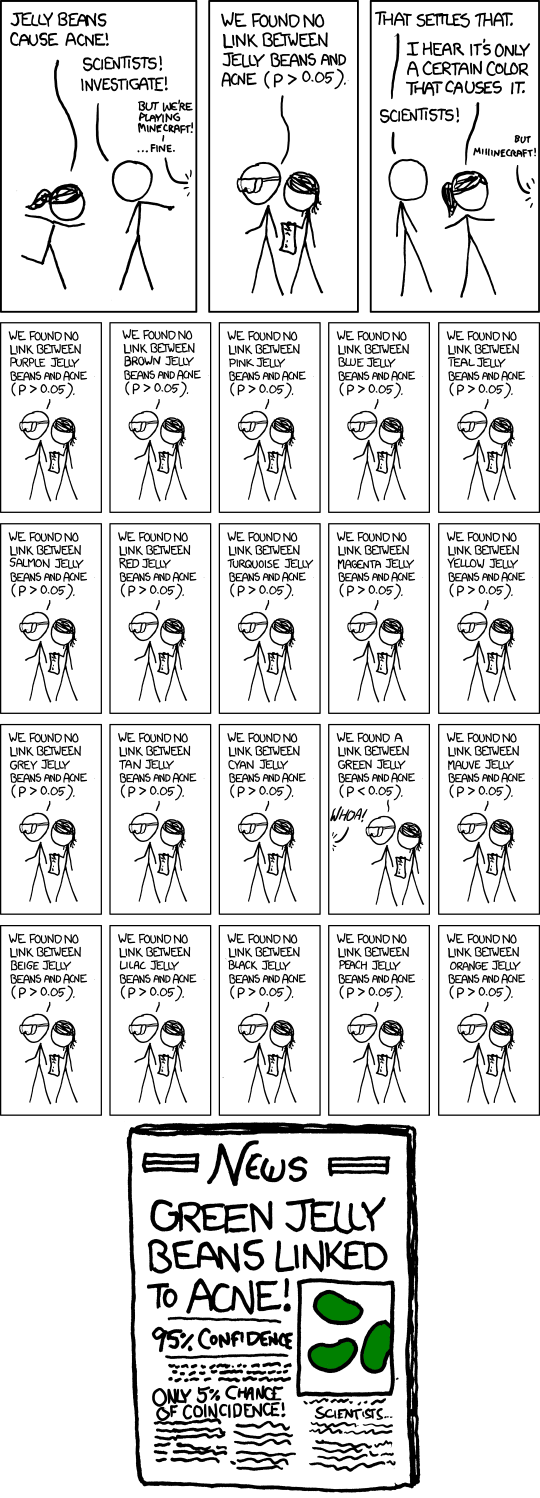

All this is aptly illustrated by this xkcd comic strip (original here):

This isn’t how to do it, obviously, but how should we treat scientific findings?

Step one: Understand what they are investigating

Before you draw any conclusions whatsoever, you need to be clear about what the researchers are actually investigating. If you find an article saying that using mnemonics isn’t very good, your first reaction shouldn’t be “Oh, I guess I’ll stop using mnemonics then”, but rather “For whom? For learning what? In what kind of situation? What kind of mnemonics?” If you find that the answers to those questions are relevant to you, you should seriously consider the results of that study. What do you think about the study linked to above? What does it tell us about learning Chinese? I leave the answer as an exercise to the reader, please leave a comment!

One of the most crucial aspects to consider is what kind of people participated in the study and how they were selected. If you’re an adult learning Chinese as a second language, any study that is based on native speaking children is useless. It means that two fundamental variables are different from your own situation and therefore any conclusions drawn are not necessarily true for you. When it comes to participants and how they are assigned into test and control group, it’s essential that the participants have been randomly assigned (they might not have been randomly selected, because that’s either very expensive or very hard to achieve).

Something which is all too common to see in less rigorous research is a situation where group using a new method or strategy volunteer to use that method and the control group just keeps going on as usual. The problem with this is that the people who are actively seeking out new learning methods are probably different from the average student. If you volunteer to spend extra time learning a new method, your motivation to learn is likely to be much higher than if you simply don’t care. It has been conclusively shown that motivation does affect learning, so a study with this kind of arrangement is next to useless.

Step two: Understand the results of the study

A common type of study in language learning is to have two groups receiving different kinds of instruction or using different learning strategies. The performance of these two groups is then compared and if the sample is big enough and randomly selected, some conclusions can be drawn that are relevant outside the study itself. This is basic scientific practice.

However, few studies claim that method A is completely useless whereas B is the perfect solution. Imagine a study evaluating different ways of teaching tones in Chinese. A likely result is that a superior method will give better student performance and that this result will be statistically significant (i.e. it’s not just due to random factors). However, this just means that B is better than A, it doesn’t mean that you can’t learn Chinese using method A.

If you have a very large sample, even very small differences in performance can still be statistically significant. Saying that method A is better than B and that the difference is statistically significant means almost nothing in itself. Therefore, it matters not only which method is superior, it also matters how much better it is than the other method. If the difference is small, individual variation might mean that for you as an individual, the results aren’t very important at all. In statistics, this is called “effect size“.

Step three: Understand the significance of the report

The kind of study mentioned above is useful because it gives us alternative ways of learning. If we’re currently using method A, but then read a report with positive findings regarding method B, we might try that one. It doesn’t mean it will work better for us, but it might. Depending on the study and the results, it might even be very likely to work well for us.

There is another kind of research result, though, one which we really should pay attention to. Some results seem to be universal and can almost be called laws. These apply to almost everybody and we can benefit a lot from knowing about them. Here are a couple of examples about memory:

- The spacing effect – It has been known for at least a hundred years that spreading out repetitions is much more efficient than massing them together. This is not only true for language learning, but almost any other kind of learning as well.

- Environment matters – The environment in which we learn matters for our ability to recall. People who memorise something in a certain situation is more likely to be able to recall that information in a similar situation. Some people suggest this is one of the benefits with flashcards (especially on mobile phones), because you review in lots of different environments.

- It’s very hard to remember meaningless things – I mentioned this in Remembering is a skill you can learn, and referred to the Baker/baker phenomenon mentioned in Joshua Foer’s excellent TED talk about memory (included in the article linked to above). In essence, things we can connect to other things we already know are much easier to remember than things we have can’t from mental connections to, and concrete things are easier to learn than abstract ones.

It’s very hard to conduct proper language learning research

The major problem facing the field of language learning research is that the variables are so many that some question the use of conducting research in the first place. Sure, we can prove one thing in the laboratory, but who says the results are relevant in a real classroom?

It’s hard to know. In real classrooms, with real students and real teachers, variables are chaotic and almost impossible to control for. This doesn’t mean that it’s impossible to conduct research, but it means that any results are bound to be restricted by the methodology of the study.

If the participants, the situation and the subject is similar to what you’re doing, then the results can be very interesting indeed, but if not, well, then you might be better of doing your own research, conducting experiments on yourself.

4 comments

Thanks Olle. Another great article.

As a scientist (PhD in Mathematical modelling) and a student of Chinese, then I am always very interested in the different ways in which we can maximise our efforts in studying Chinese, and also very disappointed by the exaggerated or unsubstantiated claims of some.

In my opinion the key things to get right are knowing what works for you, have a clear idea of what you are aiming to achieve and then having the discipline to keep working at the language over a long period of time.

Great post. Same concepts could be said of the health and fitness industry “facts” that dominate front page of many magazines.

I think there are big challenges in the research because learning results depends on motivation, technique used, skill at applying technique, and so on. So an A/B study on techniques to learn tones where one technique involves writing tones on your arm, and other involves learning to tightrope walk, then learning them on a high-wire, is going to skew towards the easy to learn technique because it gives the best results for the average person.

Maybe learning on a tightrope is the best way to learn, but we are unlikely to ever see it come from a study, because so few people will get past the first stage of learning how to do it. And so it is with techniques that are not widely understood or hard to implement. SRS is pretty easy and highly automatable, imaginative memorization requires skill to be developed. So SRS will tend to get good results for most people and gets ranked highly as a learning technique.

I found it’s more useful to consider individual success cases, and compare their situation (in terms of starting point and goal) and then consider what they did and whether you have similar skill and motivation levels to get there.

Well, there are those that study language; and the others that just use it.

I studied for a Master’s degree in Teaching English as a Second language and there is a vast corpus of research.

And the majority of it is there because of the ‘public and perish’ culture of academics.

I tend to believe that the best way to learn any 2nd language is to get into using it in a mainstream fashion. One can get lost in being a student forever.