Language research is notoriously difficult to perform properly simply because variables in a real classroom are hard to keep constant. Let’s say that we want to examine the effectiveness of a new learning strategy. In order to be able to say anything with certainty, we need a fairly large sample and we need to find a way of testing the new strategy that isn’t biased in any direction.

One problem is that in order for random factors to balance each other out, we need large, random samples. If the study becomes too large to conduct by one single teacher, suddenly different teachers are involved, too. This quickly escalates into the realm of meaninglessness. The problem is that the variation between countries, schools, teachers and individual students is bound to be large, perhaps large enough to render the results meaningless for any given individual.

If we could prove that the learning strategy was 5% more efficient than another, that doesn’t really help you, does it? Other factors will influence you more than the actual strategy you use. For instance, if you like the method or not might make much more of a difference than the effectiveness of the method itself.

Self-experimentation and n=1

How can an experiment with only one participant (n=1) be of any value? Most scientific journals will (rightfully) say “no”, because they don’t really care about you as an individual. But you care about your own learning, don’t you? Therefore, self experimentation can be of tremendous help if that single student is yourself.

If you conduct the experiment to learn more about yourself and the way you learn, no-one requires you to follow any rules, but it does make sense to follow the scientific method in general, because otherwise your results won’t be reliable even for the single student.

In case you haven’t done much research recently, here is a crash course in the scientific method:

- Ask a question – This can be anything related to how you learn Chinese. For instance, you might want to know if it matters at what time of the day you review words, if it helps retention to read the words aloud or if colouring tones helps you remember them. Since you only have one person to experiment on, you won’t be able to test things you can only do once, so you’re not likely to be able to test things like “which is the best method to prepare for HSK 3”.

- Formulate an hypothesis – In essence, this is a guess at what the answer to the question might be. According to what you know, make an educated guess. For instance, my hypothesis is that I review best in the morning and that reading aloud does help increase retention rates. I also think that colouring the tones should be useful.

- Predict consequences – If your hypothesis is correct, what kind of observable results should you be able to observe? In some cases this is very obvious. Looking at our examples, we would expect to remember more cards in the morning than at other times during the day. We would also expect higher retention rates for cards read aloud as well as better tone recall when tones are coloured.

- Test the hypothesis – This is the experiment itself by far the hardest part to get right, both in practice and in theory. We need to come up with a way of testing the hypothesis that only gives a positive result if the hypothesis is correct. The key here is to keep variables as constant as possible. For instance, we could separate our flashcards into two decks and then review one deck in the morning and the other in the afternoon, but we would have to sort the cards randomly, because otherwise one group of cards might contain easier cards on average, which will lead us to the wrong conclusion. We could also add a tag to half of our flashcards and read all those cards aloud and then check if there was any difference between the two groups. However, we need to make sure that we don’t spend more time reading those cards, because more time spent obviously means higher retention.

- Analysis – Based on the testing above, we might be able to prove the hypothesis true or false. Depending on the experiment, we might need to formulate a new hypothesis and keep on experimenting. We might also find that our result is inconclusive, perhaps because we made some mistake or didn’t design the test well enough. The goal with the analysis is to interpret the outcome of the test and determine what to do next.

How to conduct these kinds of experiments in Anki

I’ve had many debates with people who think there are better flashcard software than Anki and one of the reason I maintain Anki is superior is because of it’s flexibility. In Anki (especially in Anki 2), you can manage and edit your flashcards in bulk in almost any way you wish. Split, merge, tag, anything you want.

You want to add a tag to half the cards and add a star after the final character for all those cards (so you know which characters to read aloud)? Easy. Do you want to temporarily split all your cards into two decks, track statistics for these two decks separately and then merge them again when the experiment in done? Sure. In fact, Anki already has statistics for hourly performance.

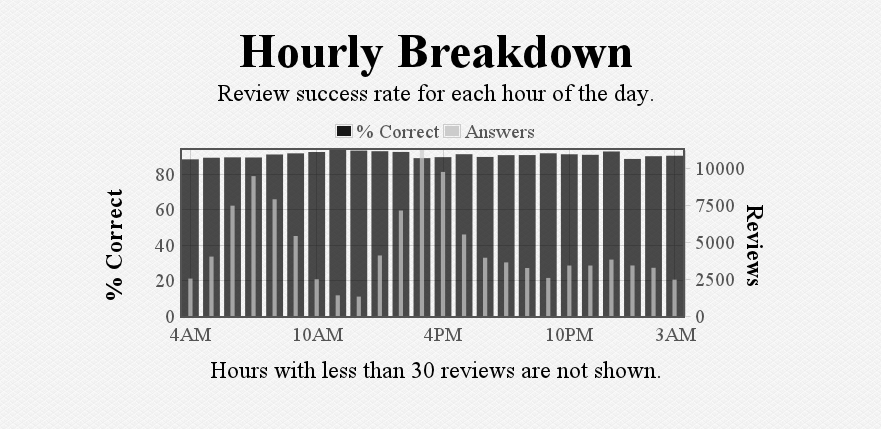

This is what my graph looks like:

There are some 113063 reviews behind those bars, so whatever differences we can see here are statistically very significant. It seems my hypothesis was wrong (obviously, I knew the answer when I wrote the article, my hypothesis was the one I had before I saw this graph). It seems I remember best when reviewing around lunch. Interesting. Not surprisingly, I have the lowest retention rate late at night.

This case happened to be rather easy because Anki already has a built-in function to check hourly retention rates, but what if you want to check something else, like if reading aloud is helpful or not? As I mentioned above, the best thing you can do is create a new deck with all words you intend to read aloud. As far as I know, you can’t sort randomly (that’s not sorting, technically), but you can sort on an arbitrary value, such as the initial letter of the English or some other factor which should be random for practical purposes, albeit not technically. Then grab half the words and change them to a new deck. Conduct the experiment and see if the groups differ. Of course, you don’t need to do this with all cards if you don’t want to, testing with a few hundred might be enough.

The two other examples I brought up yielded fairly unexpected results, actually. It turned out that both reading words aloud and colouring the tones had an effect, but that it was very small indeed; I expected the effect to be much bigger. However, remember that even though that might be the case for me, we shouldn’t extrapolate that result to you, because you might be different.

This isn’t “real” science (you probably won’t get your results published)

This isn’t” real” science, but that doesn’t mean that scientific thinking isn’t necessary. In fact, this kind of thinking is always good to adopt, even if you’re not conducting any experiments at all.

For instance, I said above that you can’t really experiment on different ways of preparing for the HSK simply because if you succeed, you can’t try again. However, you can still apply the same kind of thinking.

- What did you try to achieve?

- What happened?

- Why did that happen?

- What can you do to make it work better next time?

The results might not be reliable either, because there are many things going on that are beyond your control. Perhaps you will learn better because you know that you want one method to be better and therefore try a little harder. Perhaps you unconsciously make a hundred other small adjustments. Therefore, I wouldn’t care too much about small differences achieved over a short time with few words. If you have results like my hourly retention rates above, though, that were produced based on over 100,000 reviews, the results are probably not based on other random factors.

More than words

I’ve spent most of this article talking about vocabulary and how to pronounce characters and words, but that just happens to be a convenient example. You can conduct similar experiments in many other areas. Identify the problem, formulate an hypothesis as to how the problem can be solved, try your solution, evaluate. Repeat. Doing this will help you understand both yourself and Chinese. It will bring benefits well beyond the realm of language learning as well.

Further reading

For anyone who is interested in reading more about self-experimentation, I want to recommend Seth Robert’s blog, “Personal Science, Self-Experimentation, Scientific Method”. Apart from reading his articles, you can find many interesting links and suggestions for further reading. I also suggest Scott Young’s blog, which is about much more than self-experimentation and offers clear thinking on many different topics.

12 comments

I’d never thought of approaching language learning so scientifically. Turns out I can put my physics degree to some use after all! 😉

Seriously though, when trying new methods I’ve only really thought about whether I like them but analysing effectivity should definitely be part of it too.

I have an idea for an experiment on fluency.

I wanted to get your opinion.

One of things I’m interested in is “fluency”.

I have a friend who says that his 3.5 year old son has become fluent in Bengali without any teaching.

So, let’s say a 3 year knows 1,000 words (I don’t really know). If he is fluent with those 1,000 words, it means he can manipulate those words almost without thinking.

I’ve heard you say something like “it is not how many words you know but how well you can use them”

But I’ve never seen anyone talk about strategies where you purposely limit the number words and try to become fluent with that small set of words.

So, my experiment would be to take 50 words and create every possible sentence and expression from those 50 words. I’d probably need someone who is fluent to help me with that task. And then drill on manipulating those 50 words (speaking) over and over until I can do this very quickly and also listening to the sentences over and over – perhaps spoken by a native speaker and normal speaking speeds.

Then add another 10 words and and generate more sentences and practice with that for a while. So, instead of focusing on learning lots of new words, focus on getting really spontaneous with this smaller set of words.

Have you ever heard of anyone doing this?

Do you think this would be a useful exercise?

Thanks,

John

Olle,

The other experiment I’m thinking about is memorizing dialogs. My Bengali friend, who speaks about 6 languages, said he learned languages by memorizing text.

He would be given a short story. He had to be able to write and speak this story from memory. Once he could do that, he was given another story. He just kept repeating this process over and over.

I noticed that when I try to speak spontaneously I only have the words and expressions that I know really well.

I think that I know several thousands of words (passively) but they don’t come to mind when I’m speaking.

Maybe memorizing dialogs is the way to get more words available for speaking.

What do you think of this experiment?

Thanks,

John

Olle,

I thought this post was pretty interesting and sent through two replies on it… both pretty in depth… however don’t see them here or your response… did you receive them ok? Hope so! ; )

I’m sorry, but I’m unable to find your comments. I have looked through the spam filter, too, and I can’t find anything. Did you use the same e-mail and name as for this comment?

Glad to have found your site. I apply a lot of self-experimentation ideas to teaching and doing yoga. And I’m trying to do the same with learning Chinese (since I live in Taiwan.) Nice to find someone who can explain it so well.

Hi,

I love this article! Because I’m a big fan of improving by self experimentation I want to add two things here that confused me in the beginning. Maybe it helps someone else as well.

1. How to get from the question to a hypothesis and how to formulate a meaningful prediction? Here is where other science comes in. Instead of doing what some newspapers do, who take the truthfulness of research for granted, the smart scientist reads a lot of other information, summarizes it, verifies it, and uses it to formulate his own hypothesis and prediction. If you don’t have any hypothesis yet or can’t argue about it based on other texts, then you probably haven’t read enough about the topic yet. Of course with this method you don’t have to limit yourself to scientific material. For most self experiments normal blogs, books, videos etc are also fine. They are just the sources and past experiences of others you use to improve your experiment.

2. Measuring: Although measuring all the time can be counterproductive (as is mentioned in another blog post on this website as well), when you do an experiment it’s very important. Doing an experiment to check whether method A makes you “more fluent” can’t be verified objectively enough. It is better to formulate a goal like “after learning with method A for two weeks (specific!) I will be able to speak 10 minutes with my girlfriend in her mother tongue compared to the 2 minutes I can manage now.” This is a S.M.A.R.T. goal and you can easily check how successful your experiment was.

Great blog! Mostly very well written, both contents and style, but this one is inelegant: “…because variables in a real classroom are hard to keep constant.” Something can either be variable or constant.

When conducting experimental research, it’s important to keep as many variables as possible constant, i.e. only allow one variable (the one you want to study) to vary. I don’t see any problem with the sentence you quoted. There are many variables and it’s hard to keep them constant when conducting research!