I’ve been teaching beginner courses in Chinese for more than ten years, but I still remember what it was like to write my first characters.

I’ve been teaching beginner courses in Chinese for more than ten years, but I still remember what it was like to write my first characters.

When starting to learn Chinese characters, one of the first questions that pop up is how to learn them. I don’t mean what characters to study, how to make sense of Chinese characters or principles for stroke order, but what to do as a beginner to learn your first characters.

When learning almost any other language, writing by hand is not a challenge in itself. Sure, there’s spelling and other things to learn, but that’s at least in principle familiar from other languages we know. Writing Chinese characters is a different beast altogether.

So what do you do if your teacher asks you to learn a bunch of characters until tomorrow or later this week?

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many other platforms!

From drawing pictures to writing characters

Before we start, I want to say a few words of encouragement. Learning Chinese characters as a beginner is challenging, mostly because everything is new and you can’t connect what you need to learn to things you already know. Writing characters is essentially like drawing stylised pictures.

The more you learn, however, the more extensive your web of Chinese knowledge will become, which also means that expanding it further will become easier. The more you know, the easier it becomes to learn even more. You will start recognising components and understand how they fit together to form compounds.

Thus, if you feel that it’s difficult and frustrating at the moment, don’t worry, it will become easier soon! It might feel like you’re drawing pictures, but as your understanding of Chinese characters increases, you will be writing characters soon enough.

For general advice about learning Chinese characters beyond the specific situation we’re looking at in this article, please refer to My best advice on how to learn Chinese characters. It contains in-depth discussions about how the Chinese writing system works, methods for learning characters, and how to remember and review characters effectively.

As a beginner, you don’t have time to read all that now, though, especially not if you have a test soon, so let’s talk about that! If you have time to spare, investing more of it into understanding Chinese characters is always good, but not always practical. I’ll return to this later, but let’s go through the basics first.

8 principles for learning Chinese characters as a beginner

Here are eight practical principles for how to learn to write Chinese characters:

Study the character closely, including stroke order – Before you start to write, study the character you’re going to write carefully. How is it written? What does it look like? If your textbook or teacher didn’t provide you with information about stroke order, you can use apps like Pleco or websites like Archchinese. If you don’t know how to type the character to look it up, take a look here. Also, note how the character is pronounced, what it means and if it has any components. If this information is not readily available or doesn’t make sense to you, just ignore it.

Study the character closely, including stroke order – Before you start to write, study the character you’re going to write carefully. How is it written? What does it look like? If your textbook or teacher didn’t provide you with information about stroke order, you can use apps like Pleco or websites like Archchinese. If you don’t know how to type the character to look it up, take a look here. Also, note how the character is pronounced, what it means and if it has any components. If this information is not readily available or doesn’t make sense to you, just ignore it. Write the character until you get the feel for it – Once you know (in theory) how to write the character, write it until you can write the entire character without thinking too much. This is just to familiarise yourself with the hand motions involved and will help improve your handwriting in general, but it isn’t very good for memorisation. The number of times you need to write a character varies greatly depending on the complexity of the character, but don’t overdo it. Write the characters on a paper with squares of suitable size (a few centimetres). I’ve collected stroke order resources and tools to generate grid paper here.

Write the character until you get the feel for it – Once you know (in theory) how to write the character, write it until you can write the entire character without thinking too much. This is just to familiarise yourself with the hand motions involved and will help improve your handwriting in general, but it isn’t very good for memorisation. The number of times you need to write a character varies greatly depending on the complexity of the character, but don’t overdo it. Write the characters on a paper with squares of suitable size (a few centimetres). I’ve collected stroke order resources and tools to generate grid paper here. Don’t copy characters stroke by stroke; use active recall – If you can remember how to write the whole character in one go, that’s great. If you can’t, break it down into its component parts and peek at the stroke order only between writing each component. Copying stroke by stroke is next to useless because you’re not even trying to remember anything. The more you try to remember something, the better you will become at actually remembering it. In general, don’t look at what you’re trying to memorise (passive recognition), but instead, hide the information and remember it on your own (active recall). This is part of the reason why flashcards work so well for learning Chinese characters!

Don’t copy characters stroke by stroke; use active recall – If you can remember how to write the whole character in one go, that’s great. If you can’t, break it down into its component parts and peek at the stroke order only between writing each component. Copying stroke by stroke is next to useless because you’re not even trying to remember anything. The more you try to remember something, the better you will become at actually remembering it. In general, don’t look at what you’re trying to memorise (passive recognition), but instead, hide the information and remember it on your own (active recall). This is part of the reason why flashcards work so well for learning Chinese characters! Once you know the character, don’t mass your repetitions – Even though you have now written the character a few times and can write it from memory if asked to do so right now, this ability will fade very soon. If you want to be able to write the character tomorrow, or maybe even an hour from now, some reviewing is necessary. Some people (including most native speakers) write the same character again and again, hoping that they can etch them into their minds. This works, but it’s very inefficient. Instead, you should spread out your repetitions over time. Write other characters, do some listening practice or just do something else entirely for a bit. Spreading reviews like this is several times more efficient than writing the same character over and over. While there is software that helps you schedule your reviews effectively, you don’t need to commit to any app or service right now, just don’t mass your repetitions. You can even create your paper flashcards for your first few weeks of learning while you check out the spaced repetition software on offer.

Once you know the character, don’t mass your repetitions – Even though you have now written the character a few times and can write it from memory if asked to do so right now, this ability will fade very soon. If you want to be able to write the character tomorrow, or maybe even an hour from now, some reviewing is necessary. Some people (including most native speakers) write the same character again and again, hoping that they can etch them into their minds. This works, but it’s very inefficient. Instead, you should spread out your repetitions over time. Write other characters, do some listening practice or just do something else entirely for a bit. Spreading reviews like this is several times more efficient than writing the same character over and over. While there is software that helps you schedule your reviews effectively, you don’t need to commit to any app or service right now, just don’t mass your repetitions. You can even create your paper flashcards for your first few weeks of learning while you check out the spaced repetition software on offer. Practise pronunciation and meaning at the same time – If you’re writing characters, you should pay attention to and practise pronunciation as well as the character and its meaning. Write Pinyin and meaning above or below the character. If you’re sure how it’s pronounced, say it aloud. If not, mimic the pronunciation here or in your textbook (more pronunciation resources here). Do not guess the pronunciation based on the letters used to spell “i”, because Pinyin has several traps and pitfalls you need to be aware of as a beginner! The reason you want to be mindful of pronunciation when writing characters is that a vast majority (~90%) of characters look the way they do partly because of how they are pronounced.

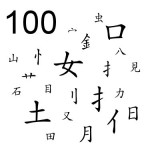

Practise pronunciation and meaning at the same time – If you’re writing characters, you should pay attention to and practise pronunciation as well as the character and its meaning. Write Pinyin and meaning above or below the character. If you’re sure how it’s pronounced, say it aloud. If not, mimic the pronunciation here or in your textbook (more pronunciation resources here). Do not guess the pronunciation based on the letters used to spell “i”, because Pinyin has several traps and pitfalls you need to be aware of as a beginner! The reason you want to be mindful of pronunciation when writing characters is that a vast majority (~90%) of characters look the way they do partly because of how they are pronounced. If you see a character component reappearing in different characters, look it up – It’s much more interesting to learn characters if you learn a little bit about them, and understanding what you are doing also makes it easier to remember characters. You can use The Outlier Linguistics Dictionary of Chinese Characters to learn about what the components mean and why the characters look the way they do. A free alternative is YellowBridge, but be aware that it is less accurate and much less detailed. If you don’t know which components are important to learn, you can check this article: Kickstart your character learning with the 100 most common radicals. A general rule of thumb is that if you see a component three times in different contexts, you should learn it.

If you see a character component reappearing in different characters, look it up – It’s much more interesting to learn characters if you learn a little bit about them, and understanding what you are doing also makes it easier to remember characters. You can use The Outlier Linguistics Dictionary of Chinese Characters to learn about what the components mean and why the characters look the way they do. A free alternative is YellowBridge, but be aware that it is less accurate and much less detailed. If you don’t know which components are important to learn, you can check this article: Kickstart your character learning with the 100 most common radicals. A general rule of thumb is that if you see a component three times in different contexts, you should learn it. Diversify your character learning – One way to spread out your studying is to make use of many different kinds of learning. Here are some examples: create paper flashcards you can carry with you, write characters you find extra hard on your hands, paste characters all over your apartment, and download a flashcard app. Learning shouldn’t only be done in front of your desk. Diversifying your learning will vastly increase the time you can spend learning characters. Read more here: Diversify how you study Chinese to learn more.

Diversify your character learning – One way to spread out your studying is to make use of many different kinds of learning. Here are some examples: create paper flashcards you can carry with you, write characters you find extra hard on your hands, paste characters all over your apartment, and download a flashcard app. Learning shouldn’t only be done in front of your desk. Diversifying your learning will vastly increase the time you can spend learning characters. Read more here: Diversify how you study Chinese to learn more. Read and type more – Even though this article is about writing characters, it’s important that you spend as much time as possible reading Chinese. This will in itself not allow you to write all characters by hand, but it will help you get familiar with what characters look like, in what contexts they appear in and how they function in sentences. Handwriting is after all not a goal in itself, and isn’t even strictly speaking necessary in most real-world situations. Beyond your textbook, you can use additional textbooks or find beginner-friendly reading resources online. You should also make sure to install Chinese language support on your phone and computer so you can start typing Chinese. That won’t teach you how to write by hand either, but it’s more active than reading the way most people communicate in written Chinese these days.

Read and type more – Even though this article is about writing characters, it’s important that you spend as much time as possible reading Chinese. This will in itself not allow you to write all characters by hand, but it will help you get familiar with what characters look like, in what contexts they appear in and how they function in sentences. Handwriting is after all not a goal in itself, and isn’t even strictly speaking necessary in most real-world situations. Beyond your textbook, you can use additional textbooks or find beginner-friendly reading resources online. You should also make sure to install Chinese language support on your phone and computer so you can start typing Chinese. That won’t teach you how to write by hand either, but it’s more active than reading the way most people communicate in written Chinese these days.

https://www.hackingchinese.com/beginner-chinese-reading/

Learning Chinese characters as a beginner: Beyond the first encounter

The above advice should help you survive the small but regular tests that are probably sprinkled all over your course schedule. However, the strategies that help you in the short term will not suffice in the long term. I have already recommended my article about general advice for learning Chinese characters above, but beyond that, you must get to know the Chinese writing system and understand how it works. Learning meaningless things is both hard and tedious, so if you familiarise yourself with the basic principles that underlie all characters, everything will become much easier. In the best of worlds, teachers should explain these things, but this is far from always the case. Thus, I’ve written a series of articles about this, starting here: The building blocks of Chinese, part 1: Chinese characters and words in a nutshell

Learning to write and read in Chinese takes a lot of time and effort, but it’s not as hard as it might seem at first. Sticking to the advice in this article will prevent you from making some of the more egregious mistakes. Good luck!

Unlocking Chinese: The Ultimate Guide for Beginners

I have built an entire course meant to help you get off to a good start with your Chinese studies. It’s called Unlocking Chinese and you can check it out here.

45 comments

A topic near and dear to me.

I really like the image you chose for this article.

Funny you should say that, check the discussion on Facebook. 🙂

thanks, I find your advises very helpful, also the resources linked. I’ll definitely have a lot on them!

For the beginner, overview is often ignored and makes the learning process more intimidating.

Just about everyone can look in a Traditional Chinese character dictionary and see that the most complete radicals are 17 brush stokes, but has anyone every shown you how many total brush strokes there are are in the longest of Traditional Chinese characters?

The answer is 33 brushstrokes. And for some beginners, it is comforting to know there is a limit. It also makes them aware of the dictionary index that lists characters by total brushstokes.

If you just start out at the low end of the brushstroke count and think you can work eventually to the top end, you might never arrive.

Use the whole dictionary and ALL the indices provided. Spend an afternoon exploring and writting those 33 stroke characters, just to get an idea of the look and feel of the densest of the Chinese characters.

You may someday come across one and not be daunted by the high brushstroke count end of the dictionary.

i have actually never heard about anyone doing that. As far as I know, all courses and all textbooks are based on the frequency of the words and/or characters (and, of course, their practical usage to beginner learners), not the number of strokes they contain. A number of fairly complicated characters typically appear very early, especially if one is learning traditional Chinese (聽、國、會、學、還、樣、etc. come to mind).

High frequency approach is quite common teaching 2nd language lexicon in any language. But the problem with such an approach in Chinese is that it completely avoids the written lexicon for names or more fancy characters used in advertising.

When one turns to reading real world Chinese signage and newspapers, the lexicon is a bit too limited. One can enjoy elementry school and middle school texts, but I am rather weary of being set apart from the mainstream.

If you study geography in Chinese, you soon see a lot of odd and exotic characters in the namespace for locations in China.

If you can get a copy of the Taiwan Yellowpages, you can get a better idea the namespace for products and services by the headings listings in the index.

But both are a lot of work and ambitious projects.

The student doesn’t just need what the linguists calcualte as high frequency and I see a lot of 2nd langauge English learners that hit a plateau with such that they never get beyond.

It takes some individual initiative and exploring to break through such an artifical pleteau which is often called a creole or pidgin.

The reality is that we are always learning new lexicon in all the languages we know or try to know. Otherwise, our ability to communicate falls behind.

Just now looked up your facebook page and the related comments. Interesting, actually, the naming of the strokes is what I liked most about that post in the first place. I really think learning the names of the different strokes is cool. Funny, as that was the exact opposite of your comment about learning stroke names on facebook… haha. (Different strokes for different folks, aye?! Pun intended… hehe).

As to the issue at hand, that the original “yong” character photo you used and the names of the strokes, can you send me the original photo or at least a link to it?

I want to do some additional research on those stroke names… as you mentioned, my guess would also be it wasn’t a mistake, rather perhaps a different way to name those strokes… still, got to research it to be sure and I didn’t save the original photo… ; )

PS: Also, saw on your facebook page if anyone is interested about advertising on your site to contact you… email me on this, I’m interested… ; )

Just another thought.

Reading and Writing Chinese, revised edition. by McNaughton and Li is one of the older more established texts for study of the written characters, based on the Yale University texts for learning Chinese.

It is intended to help you associate English words with each as you go along progressively in the first 1020 items and includes the “Official 2000 list”.

It really helps you have an English name for each component of a character, some are obscure and originate out of history that the text mentions.

It is very complete and mentions the Simplified character when different. The general concensus is you need to learn these 2000 to read a Chinese newspaper.

I like the rest of your comment, but this is just wrong. There is no such consensus. If you happen to know the two thousand characters in an article, sure, that will be enough, but if you know the 2000 most commonly used ones, no way. This will probably lead some a situation where you can mostly understand the structure of sentences and perhaps some content, but without understanding almost any keywords. Also, the important thing isn’t necessarily how many characters you know, but how many of the words based on those characters you know. Still, 2000 is way too low regardless how you count.

I think this is what many beginners don’t realize,”The important thing isn’t necessarily how many characters you know, but how many words based on those characters you know.” I know enough characters that I can recognize almost all (over 95%)of the ones I come across in a newspaper or magazine, but I still can’t understand everything because I don’t know the meaning of some words.

Indeed! In addition to that, I think keywords in articles are usually harder than the rest of the article, which means that you might know 95% of an article, but the 5% you didn’t know turned out to be really crucial. In any case, knowing 95% of the characters does NOT equate to a 95% understanding of the article. 95% of the words comes closer, but is still not accurate.

so I’m curious, what is the answer to this? I’ve finally started this year trying to concentrate more on hanzi, having made do, in the past, with mostly oral knowledge to get by. I’ve been going through some kids’ workbooks for writing hanzi, and doing some writing practice on other hanzi that are among the more frequently used, especially ones I’m needing in particular; I have a reference book of characters that has them organized in order of frequency of use, as you have mentioned. One of the other tools for studying that I picked up was a character a day pad, thinking, if I can’t do longer study on a particular day, at least I can do one character. The earlier ones are pretty easy and I’ve been wondering whether to use each for a few days and do the associated words (not just 一 but 一个, 一本, 一次), etc., but that almost seems to negate the purpose of the one a day pad. Would you recommend just going through the most commonly used and then adding on 2 character words/expressions after? Maybe I’m just in a strange place because I’m both a beginner and not, having lived in China for a few years.

Good question! I think it definitely makes sense to learn words that contain the characters you’re learning, particularly if you can find words that contain only characters you have studied. You don’t want the number of new characters to explode because of this. Both approaches work, though, but I prefer learning and teaching things that are immediately useful, and that means you have to learn words. Some people have reported that they learnt lots of characters successfully by learning individual characters first, but you have to play the really long game to even consider that.

ah.. this is a bit awkward. I previously mentioned that the ‘namespace’ of any language is a special set that is set aside from high frequency words. Learning names is important to establishing a topic, a context and discussion in detail.

So I tend to agree that the 2000 words will not carry you entirely in reading a newspaper.

Additionally, the issue of learning Chinese words as many characters are bound forms (these only are used with other characters).

Historically, I believe Yale promoted the idea that the 2000 characters were needed to read newspapers.

Learning names does demand some special resources. I’ve two dictionaries out of Hong Kong that group lexicon by topic and they are very helpful with vocabulary used in a specific context.

A Paractical English-Chinese Pronouncing Dictionary b Janey Chen

Getting Around in Chinese by Marco Liang.

Nonetheless, if you are just a beginner to writing and recognizing characters, 1000 are going to keep you busy for quite some time… 2000 even more.

Recognizing characters in real context is very helpful, but these book will get things started.

I’m a beginner and I didn’t know about this “consensus”. I find it quite similar to the Jooyoo Kanji list, which is an official Japanese hanzi list of the main 2000-something kanji you should know when reading newspapers etc.

This is why I think 2000 hanzi for Chinese language is not a feasible basic set since, in my opinion, Chinese text requires more hanzi than Japanese text requires kanji. But I could be wrong since I just started learning Chinese recently^^.

Oh wow thank you ^_^ I am absolute beginner focusing on characters right now and being self study it’s really hard but these tips are a major help xD

Thank you – 🙂

Some words are linguistically transparent (easy to recognize their meaning), other words are lingusitically opague (specialized, used less often or less widely) and difficult to find out their meaning.

2nd language teaching generally starts out with the transparent words (the words most often used and most acceptible to general public), the opague lexicon we have to learn more from actually asking people what the words mean.. via social networking.

But just starting out with character recognition is a bit visually challenging. I strongly suspect English users and Chinese users develop different parts of the brain in recogizing written words. English users can easily recall long strings of letters, Chinese users can recall subtle differences in meaning that the addition or omission of one brush stroke indicate.

In the beginning, i spent many months just memorizing and writing the list of radicals to help this process along. But there are other bits of characters besides the radicals.

Reading and Writing Chinese by McNaughton and Li tries to help you by explaining these bits, not just whole characters. Some bits used to be stand alone characters, but no longer are.

Simplified Chinese takes the whole process one large step forward and futher away from the history. It may be easier to learn, but you can’t easily go to older Chinese literature as you pretty much are tied to Chinese in print only after the 1940s.

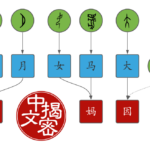

Many thought it is difficult to learn Mandarin Chinese. It is not quite true! In my opinion, Chinese is one of the most interesting languages in the world! Chinese is a picture language, which means ancient Chinese people draw different pictures as Chinese characters out of everything they saw in the environment!

Therefore, the best way to learn well the language, in my view, is to learn the radical of the characters first, which by itself usually has a hint from the writing (or drawing) and then forms the character.

Just share a final thought, It takes efforts to learn Mandarin Chinese well, but what doesn’t?

Editor’s note: I deleted the last part of your message. You have the opportunity to add an URL to your name when you comment (which you have done), which is fine. Advertising which is completely unrelated to the article in question is not okay, though, which is why I have edited your message. I hope you understand and don’t mind!

Actually, very few characters are pictures, but in general, I agree with what you say. I have written about this in many, many articles (including this one) and I don’t really see where our opinions differ? I always stress learning radicals and character components.

Thanks for tweeting this archived post Olle.

Do you think memorizing how to write a character (including stroke order) should be a beginner task? I’m eager to hear your thoughts on this.

If I were to base a recommendation to learn characters from my limited experience it would probably look more like:

1) Learn to recognize 100 most frequent characters by image alone.

2) Learn to recognize 100 most frequent radicals by image alone.

3) Learn to recognize 500 most frequent characters via radicals (and relearn any of the first 100 via the new radicals)

4) Learn to write the 100 most frequent radicals.

5) Learn to recognize the 1000 most frequent characters.

6) Learn to write the 250 most frequent characters.

etc.

Practicing handwriting, from my experience, takes perhaps an order of magnitude more time to learn than accurate recognition.

Order depends on learning goals, of course, but being able to read some beginner graded readers would be an achievable milestone more quickly reached than if you dove straight into memorizing stroke order and the proper formatting of the hanzi.

Your thoughts?

I can’t back this up with research (although there might be research available), but I think writing characters from the very start is worthwhile. Of course, it might not be necessary to write all characters, but I don’t think it’s necessary to learn how to read characters before you learn to write them. Instead, which characters you learn to write should be based on some kind of logical sequence of what makes sense (based on which radicals are taught and so on). The same is true for reading, but reading is more determined by what you want to read (i.e. normal Chinese), so you can’t avoid learning some really common characters like 我 just because it doesn’t fit in the general sequence. Okay, yes, you actually can do that, but it’s not practical for most people. I usually stress passive knowledge before active, but I do think the process should be parallel when it comes to learning characters as a beginner.

Interesting.

I think it probably makes sense to learn to write basic characters + radicals early on simply because that will give you different mental tools for processing and categorizing any characters you learn to recognize. Definitely a mistake I made, since without having practiced drawing the radicals, I couldn’t mentally categorize them properly.

-Scott

I also think it’s a matter of processing depth. It’s true that it takes magnitudes longer to learn to write something, but since these characters (radicals and common components) are so common, you really need that. It’s probably wasted effort to learn to write rare names of dishes, people and places, but when it comes to common characters and radicals, I think the time is well spent.

To weigh in on this I think it depends a lot on learning objectives.

It’s now very easy to get by with typing Chinese on a phone/computer. This requires recognition but not reproduction skills (at least not as much as one requires when writing by hand).

Increasingly I recommend early beginners not to stress too much about the characters and to focus on getting a grounding in spoken Chinese first (which is much more straightforward once the “alienness” of the tones has been surpassed). Even at the point of learning the characters I think it is still worth having a long hard think about whether handwriting is a necessary/desirable goal.

Focusing on recognition and typing alone allows for written communication to be a reality much much faster. And in reality the vast majority of written communication we do nowadays (in our mother tongue or otherwise) is digital rather than handwritten. Thus deciding whether to spend months if not years mastering characters by hand is a serious question every beginner needs to consider.

That said, I definitely think it helps all beginners to learn to handwrite the most common radicals and characters.

Perhaps not in week 1 but at some point during the first few months of study (I bitterly remember trying to write 我 by hand…wow that’s an annoying one to start with!).

Being able to reproduce the first hundred characters or so by hand helps massively with later recognition, learning and remembering because it gives the brain more mental hooks/reference points to work with.

Manually grinding through those first hundred or so radicals/characters helps to understand the logic of how the characters are put together. A tough but important rite of passage!

I’m an intermediate learner (or somewhere between beginner and intermediate at least). One of the things I do that I really enjoy because it helps me so much, is to look up the word that I’m learning in a Chinese dictionary. After you go down the rabbit hole of adding the words in the definition and adding the words you don’t know in the definition of the word from the previous definition things start to repeat, eventually. 🙂 It’s really helpful once you get past the initial hump of not knowing most of the words in the definition! And using pictures so you can learn the language without translating is super helpful. I think you (the writer of the article, the guy whose website this is) should link to this article where people can find it, because I 100% agree with his method of learning a language with adding pictures to flashcards make it not need translation.

Precious advice, my sincere thanks 🙂

Thanks for this article.

I had to put some chinese text into a document, and I became curious about how someone would learn to write the characters.

I never thought they consisted of separate components so that’s good to know 🙂

Thank you for this article!

I’ve been learning Chinese for quite a few months. It is really a hard language for m to learn. Your articles are really helping me a lot.

I want to learn Chinese

Great! You can find some general advice for beginners here. If you’re interested in content that isn’t free, you can check out my beginner course Unlocking Chinese.