Most of us use textbooks and go to class in order to learn Chinese, but this is merely the beginning of a journey or a method to reach something farther down the road. The real goal is to be able to understand and produce Chinese as it is used by native speakers out in the real world; the textbooks and the courses are simply stepping stones making the journey easier.

However, there is a problem. Chinese is quite different from English (or other Indo-European languages) and without any guidance at all, it’s hard to make sense of an unmediated immersion environment. One of the most frequently asked questions I hear from students is how to approach real Chinese (usually meaning authentic or non-learner oriented). They feel that what they have learnt is of only limited use and that the way Chinese is so much more complex and varied that what they have learnt, making it hard to just dive in, feeling that drowning is a more likely outcome than learning how to swim. In a sense, there is a gap between classroom Chinese and real-world Chinese, both in terms of difficulty and actual content.

However, there is a problem. Chinese is quite different from English (or other Indo-European languages) and without any guidance at all, it’s hard to make sense of an unmediated immersion environment. One of the most frequently asked questions I hear from students is how to approach real Chinese (usually meaning authentic or non-learner oriented). They feel that what they have learnt is of only limited use and that the way Chinese is so much more complex and varied that what they have learnt, making it hard to just dive in, feeling that drowning is a more likely outcome than learning how to swim. In a sense, there is a gap between classroom Chinese and real-world Chinese, both in terms of difficulty and actual content.

Still, there are many people who have bridged that gap (including myself) in Chinese or other languages. There are also teachers that have helped students to bridge the gap. Rather than presenting my own opinion on Chinese immersion in the usual manner, I wanted to ask these people what they thought about it.

As you can see below, the answers are many and varied, but they have one common denominator: Immersion is about doing, it’s about trying and winning through. It might be scary, but the only way to learn to swim is to get wet. Many also stress that even if it looks frightening, it’s actually not that bad and there are many thing you can do to make it easier. This is encouraging; can we bridge, the gap, so can you!

The question I asked was this:

How do you bridge the gap from textbook/classroom Chinese to real immersion?

Now, I didn’t offer any definition of what I meant with “real immersion” or what constitutes “classroom Chinese”, because I wanted breadth and variation. Thus, the answers vary not only in their actual suggestions and advice, but also in how they interpreted the question. some people reject the idea of the gap altogether, which of course is a valid approach!

Expert panel articles on Hacking Chinese

- Asking the experts: How to bridge the gap to real Chinese (this article)

- Asking the experts: How to learn Chinese grammar

This type of panel question is an experiment here on Hacking Chinese, so if you like it, please let me know. If you have questions that you would like to ask a similar panel in the future, leave a comment or send me an e-mail. Enough for me now, though, here’s a list of the contributors with links to their answers:

- Alan Park

- Albert Wolfe

- Ash Henson

- Benny Lewis

- Carl Gene Fordham (separate article)

- David Moser (separate article)

- Furio

- Greg Bell

- Hugh Grigg

- Imron Alston

- Jacob Gill (高健)

- John Fotheringham

- John Pasden

- Keoni Everington (华武杰)

- Mark Rowswell (大山)

- Niel de la Rouviere

- Roddy

- Sara Jaaksola

- Steven Daniels

- Yangyang Cheng

- Chinese Forums

You can also read my afterword here.

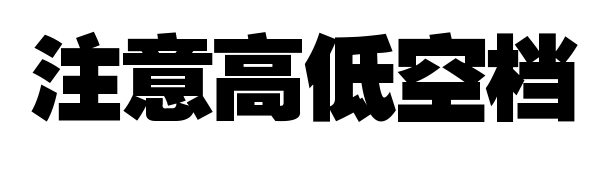

Mind the gap!

Alan Park has been studying Chinese for 13 years and previously worked in China with Chinese clients as a management consultant. Currently, he is the founder of FluentU, a site that brings language learning to life with real-world video content.”

Why do Chinese learning classes use scripted textbooks while many of the most successful learners swear by immersion through real-world content?

It’s because real-world content is a double-edged sword and you can easily cut your arm off. The potential benefits are huge – it’s more fun, more memorable, gives you insights into Chinese culture, and teaches you natural conversational Chinese. On the other hand, the challenges are also great – real-world content is just plain difficult and not designed for beginners.To make it work and take full advantage of the benefits of immersion and real-world content, what I did for myself was create an efficient workflow that let me:

- Find content that was appropriate for my level and matched my interests

- Get enough support (“scaffolding,” as they say) so that I could truly digest that content

- Review those words in context and at the right time

- Continue to find new content which had the right level of vocabulary overlap with words I had already learned through this workflow

This sounds like a lot of work and it was. Ultimately, I got tired of piecing together various tools and websites and so I decided to create a solution from scratch which was built specifically for this purpose. If you would also like to do this the easy way, I would recommend that you try language immersion through FluentU.

—

Albert Wolfe started learning Chinese on his own when he came to China in 2005. He is the author of Chinese 24/7: Everyday Strategies for Speaking and Understanding Mandarin and a novel faceless and the blog LaowaiChinese.net.

The gap between “book learning” and “street smarts” is a common problem for language learners. In my sixth month in China I met a young guy from England in a hotel lobby. He had done at least one year of formal Chinese study in England but was having difficulty communicating with the receptionist. I was able to help translate for him even though I’d never taken any Chinese classes. Or was it because I’d never had any classes?

My language learning had been entirely reactive. In other words, I was constantly drowning in the “real world” of Chinese and only kept myself afloat by learning things that were most essential to me (including how to communicate with hotel staff).

All language instruction books (including my own) share the same fundamental flaw: the authors are just guessing about exactly what learners “need to know” and the order they should learn stuff in. Some of those guesses are pretty accurate (the numbers, pronouns, “hello,” “thank you”, etc.) but then comes that endless ocean of vocabulary and grammar that just continues into the horizon: the real world of Chinese language. It’s no surprise that language instruction texts often leave learners feeling unprepared for real world interaction. How was the author to know what you were going to encounter in the real world?

It was very early in my first months in China that I learned the word for “manhole cover” (下水道口盖子xià shuǐ dào kǒu gài zi). Why? Because in Nanchang, the city I was living in, manhole covers were frequently stolen and sold for scrap metal leaving road hazards for cyclists such as me. I saw that happening around me in the real world, wanted to talk about it in Chinese, and learned the necessary vocabulary and grammar to do so. But what first-year Chinese textbook author would ever think to include that little nugget?

All this means that there is only one solution to the gap between book-learned foreign language and the real world usage of that language: you. You are the bridge. Only you know what you want to say. Gazing out across the huge ocean unknown language stuff can be scary. Books and classes can give you the basics of how to use the oars and a compass, but there’s no substitute for just getting into the boat and pushing off.

—

Ash Henson – Avid language learner, after working as an engineer for 8+ years, left to pursue a language-related career. Currently working on a PhD in Chinese at National Taiwan Normal University. Research interests include Old Chinese phonology, Chinese paleography, the Chinese Classics and excavated texts.

Language immersion is not only thought of as the Holy Grail of language learning, it is also the most common excuse I hear to not learn a language. “I just don’t have the environment for that.” If you don’t want to learn a language, that’s fine, but don’t blame it on not having the proper environment. With the proliferation of the internet and legally free downloadable software, basically anyone can create an immersion environment. Having said that, let’s talk a little more about the different types of immersion and when they are appropriate.

There are at least four types of immersion: listening, speaking, reading and writing and they should occur exactly in this order. Immersing yourself in a language in the wrong order will cause damage that may take years to repair (voice of experience speaking). The first type, listening, is not only the most important, but also the most neglected. Modern education is so focused on the written word that we’ve bought into the ridiculous idea that languages are best learned by reading and writing. Idahosa Ness does an awesome job of describing this problem and how to free yourself from it here: http://www.fluentin3months.com/sound-rehab/ .

I’ve spent the last 20 years learning languages and even left a career as an engineer to pursue a language related career. I’m currently in my 8th year of graduate school at National Taiwan Normal University. That is to say, I use and have been using Chinese a lot on a daily basis for an extended amount of time. I can say with a high degree of certainty that my biggest mistake learning Chinese was learning with my eyes rather than with my ears.

The optimal way to learn a language is to first immerse yourself in listening and mimicking the sounds you hear. “But I can’t hear all the sounds! How am I going to say them correctly!” You can’t hear all the sounds because you haven’t done enough listening and mimicking! Everyone who learns a language has to suffer through ear training (or ignore ear training and speak with a terrible accent for the rest of their lives).

How do you know if you aren’t doing enough listening? If, on average, you are thinking in terms of written symbols rather than actual sounds, then you aren’t listening enough. You have to develop a habit of always paying attention to the sounds of the language you are learning. But, guess what? This will also improve your grammar! Real grammar in the mind of a native speaker is sound pattern. The more you pay attention to the sound patterns, the better your grammar will be.

So what should I listen to? Listen to natural speech, like internet talk radio or tv shows and movies (as long as they aren’t too melodramatic). You use Audacity to record internet radio or movies, etc. and then listen to these recordings over and over. You can also make your own mp3s to download to a hand held device.

What should I listen for? Listen to the rhythm of the language, notice how sentence pitch changes with time; listen for short pauses; listen to what the vowels and consonants sound like. For Chinese tones, don’t think of them in terms of numbers, but listen for the rise and fall of their pitch.

Immersing yourself in reading should be put off at the very least until you have mastered the sounds (including sentence level sounds: intonation, rhythm, pitch, etc.) of the language. How long that takes depends on you and how much time and effort you put into it.

—-

Benny Lewis – National Geographic’s Traveler of the year and professional language learner. Join along on his adventure as he attempts to learn Japanese this year.

I make it all about connecting with a real human being as soon as possible. You can get a free exchange with a Chinese person one-on-one, or you can get a good teacher who lives in China for as little as $5 and get real immersion, even if it’s via Skype. By facing a real human being you will be forced to stop thinking so much about getting everything precisely right, and start to “get by” and see that making mistakes is a necessary part of the process.

If your priority is less spoken based, then take your passion and make it something real. Read a comic book, watch some videos online or a movie – whatever you plan to use the language for, use it that way now and get used to it rather than studying until some non-existing “ready day”. Today is the day you need true exposure.

—

Furio is a heavy Longjing tea drinker, a writer and an entrepreneur. You can find him at saporedicina.com, where he writes about traveling, living and working in China.

The problem with Mandarin and immersion is that if you never start reading and listening from “real” sources (that is sources that aren’t specifically meant for foreigners) you’ll never become fluent, whatever “fluent” means to you. With respect to “reading” and “listening,” I found that watching movies in Chinese language with Chinese subtitles was my best bet.

Wouldn’t I get bored, if at the beginning I couldn’t understand anything? Not really, because I was watching movies that I had already watched with English subtitles (and thus I already knew what was going on) or extremely easy to understand, such as Ocean Heaven. This is also the way I learned English, a language I never studied at school (I studied French, don’t ask me why because I don’t know).

With respect to “speaking,” unless you find a topic you love and stick with it till you master it, you’ll most luckily end up frustrated. Once you master a topic, however, you can slowly move to other fields.

The “field” that worked best for me was food. I’m obsessed with food and I would learn anything about it. I’m a sponge, when it comes down to food vocabulary. So I know how to say “I want a medium cooked steak” or “If you put monosodium glutamate on my salad I won’t pay the bill.” There are many names of vegetables that I only know in Chinese, such a “baicai.” How to call it in Italian, my mother language? No idea.

One last thing. I’m not suggesting that you stick only to one topic during your conversations or only watch movies you already know. Talk as much as you like and watch whatever you want. But if you feel frustrated or tired, then switch to English, or in the long term you’ll burn out.

—

Greg Bell – I’ve currently got two blogs going on the matter, my language learning journey one at http://zhongruige.wordpress.

Well, for me, my immersion came in the form of a graduate program in history in Taiwan. The nature of the beast meant that I had to immerse myself in the material–forcing me to bridge the gap between textbook and classroom to real immersion in an organic and no-less-than incredibly intimidating way. It was admittedly a traumatizing situation to be put into as it was literally sink or swim going in. So, of course, my experiences entering a “real” immersion environment may be different than others as my situation basically forced it upon me.

That being said, the best advice I can give to anyone wanting to make the switch: find something you enjoy and go with it! Love T’ang era poetry? Dive right in! Want to figure out Oracle Bone inscriptions? Break into it (well, not literally, they don’t take kindly to that at Sinica!). Don’t be intimidated by what people may say is “above your level” or that “you’re not ready for it yet”. Instead, enjoy the finding out the secrets and the magic behind the characters and the language. Just take it slowly and enjoy every step of the journey!

—

Hugh Grigg studied East Asian Studies at university, and is trying to keep up the learning habit long term. He writes about what he learns at eastasiastudent.net , to keep track of his progress and to try and help out other people where he can.

It’s easy to assume that if you’re outside of China then you’ve got no chance at getting immersion. This attitude could be unhelpful, because if you’re going to class with a Chinese teacher than that’s one chance at immersion right there! My advice would be to see class time for what it really is: your chance to speak and listen to as much Chinese as possible in a “live” situation, and ask your absolute best questions (without using English as much as you can help it).

I think it’s actually a waste of time to spend your classes mulling over Chinese and discussing it in English. Analysing a language is generally not very useful for speaking it well. In my experience, the amount of questions someone asks in class doesn’t seem to correlate that much with their language ability, unless they’re using the target language to ask the questions. The point is that languages are a very different kind of thing to other topics that you learn using classes and textbooks. Languages are a skill more than they are knowledge, and you acquire skills by doing more than anything else.

You can’t play piano with theory alone, and you can be a great pianist with no theory at all. Even better, there aren’t many pianists in the world, but everyone is a native speaker of a language. This is something your brain is set up to do, if you just give it the chance to practice.

My general point here is that immersion isn’t the goal in itself. The reason immersion works is because it forces you to actually use your target language, no matter what hang-ups or hesitations you have about it. It puts you on the spot. Once you realise that that can be a goal – being forced to produce Chinese on the spot and being forced to understand it on the spot – you can aim to create these ‘immersion’ opportunities for yourself.

—

Imron Alston has been learning Chinese since 2001, and in that time has spent a total of six years living, working and studying in China, mostly in Hebei and Beijing. He is an admin on the Chinese learning site Chinese-Forums.com, and is also the developer of a number of tools designed for Chinese learners, including Hanzi Grids – a tool for generating custom Chinese character worksheets, and Pinyinput – an IME for typing pinyin with tone marks.

Although this is going to sound somewhat facetious, for me I found the way to bridge the gap from textbook/classroom Chinese to real immersion was through real immersion 🙂 That worked well for me, and I’m a big believer in getting good at something by practicing that skill.

When my Chinese was at an intermediate level, I was lucky enough to be in a position where I was in China, and had a lot of spare time, and so I went looking for people with similar interests to my own (martial arts in this case), and ended up spending a large amount of my week surrounded by people who couldn’t speak English and who weren’t interested in learning, and who would be speaking to me and instructing me entirely in Chinese.

It was a bit overwhelming at first, but it didn’t take too long to adapt, and being immersed in that environment did wonders for my Chinese listening and speaking abilities, and really helped bridge the gap from textbook to real Chinese.

I realise not everyone has the luxury of being in the position to do that, but luckily with the Internet, it’s trivial to create a good language environment for yourself – TV shows, radio, books, newspapers, language exchange partners, and more are all readily available online. Simply find content that you are interested in, and make an effort to try and understand it. It will be difficult at first, but the more you do it, the easier it will get.

Important Note: This is assuming you already have a good base to start from and you are trying to ‘bridge the gap’ between that and native content. Jumping straight to native content won’t be so productive if you don’t already have a certain level of Chinese, so if you’re just starting out, you’re going to be better off following a textbook or other program.

I’m also a strong advocate of drilling specific skills. For my first few years of learning Chinese, I’d mostly avoided drilling because I saw it as ‘dumb’ learning. However after later trying it and seeing my reading, listening and speaking make great improvements, I’m now a firm believer in this for boosting language skills to the next level. I’ve written about these drills on Chinese-forums previously, so won’t repeat them here, but this post of mine has links to a number of other posts of mine containing drills for specific skills.

—

Jacob Gill (高健) – Graduate student at National Taiwan Normal University for Teaching Chinese as a Second Language. Lecturer in the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee’s Chinese Department. Academic Advisor for Skritter and blogger at iLearnMandarin. A Global Citizen, a life-long language learner and a full-time geek.

They provide a safe space to explore and learn about the world around us. Objectives are neatly organized into bullet points on a syllabus and broken down into a series of activities and assignments that help accomplish a given goal. Along with classrooms, comes teachers and textbooks. They too share the goals of learning, exploration and discovery.

In a language classrooms, teachers and textbooks often come with a certain degree of standardization, vocabulary lists, and lots of drills to help cover students along the way. They help provide a crucial foundation, but often fall short of the raw reality of an authentic language environment. With regional accents, slang, and the average speed with which native speakers communicate, it’s easy to get lost and frustrated along the way. So how to we bridge the gap between these two spheres of language learning? One way is by being mindful of the gap that exists, and then leaping over it to new and uncharted territories.

How can we really learn about given giving and receiving directions, without first getting ourselves a little lost? What better way to learn restaurant etiquette and atmosphere than by trying a few dishes from a local restaurant and fighting for the bill. For me, the most successful way to transition between classrooms and textbooks to more authentic situations is by harnessing the power of context.

Context is the greatest weapon we have for facing any situation. It allows us to make guess about what is being said, and to communicate with others using more than just words. Body language, hand gestures and a smile can go a long way to helping increase comprehension. Context allows us to apply past experiences to situations that are filled with sentences and words we don’t yet understand.

The biggest hurdle to moving beyond textbooks is often times the fear of failure or the unknown. By forcing ourselves into new situations, however, the dialogues become our own, and new vocabulary words are given a name, a face, an emotion. Most importantly these words are given a context that can be drawn upon over and over again.

If you’re looking for a place to start, try using personal hobbies or interests or maybe even a topic you’ve covered in class. Be mindful of what you know and what you’d like to learn. Start with a simple word or phrase, and give yourself a mission. Be flexible as you explore and open to making mistakes. Most importantly, just be willing to take the risk in the first place. Trust me, the reward is well worth it!

—

John Fotheringham is a serious “languaholic”, an adult-onset affliction for which he has yet to find a cure. John has spent most of the last decade learning and teaching foreign languages in Japan and Taiwan, and now shares what he’s learned along the way on his blog, Language Mastery | Tips, Tools & Tech to Learn Languages the Fun Way.

There’s no need to “bridge the gap” because there should be no gap in the first place. Learners should start with immersion from day one and then add in textbooks down the road once they’ve had significant exposure to a language in context. Only then will grammatical explanations make much sense and have any chance of sticking.

Contrary to popular belief, you do not need to live in an area where Mandarin Chinese is spoken to immerse yourself in the language. The advent of Skype, YouTube, podcasts, blogs, online news, eBooks, etc. allow you to immerse in your target language for free, everyday, anywhere in the world (assuming you have Internet connectivity).

If you can move to Taiwan or Mainland China, all the better, but don’t let your zip code be an excuse for inaction. In today’s world, the only obstacles to fluency in a foreign tongue are motivation, discipline, and time on task, not where you happen to live or whether or not you can afford language classes.

—

John Pasden is a Shanghai-based linguist and founder of AllSet Learning, dedicated to helping adult learners overcome the major obstacles they face learning Mandarin Chinese. He’s also been blogging about learning Chinese for over 10 years on Sinosplice.com.

The truth is that no materials—textbooks, podcasts, videos, whatever—are entirely appropriate for any individual learner. That’s why it’s essential that the active learner adapt all materials to his own specific needs. Obviously, a good teacher is a tremendous help in doing this, and any good Chinese lesson with a teacher will involve bridging the gap between the language introduced in the study material and the language the learner can actually put to use.

At AllSet Learning we spend a lot of time selecting the study materials most appropriate for a given learner. That way, there’s less “bridging” that needs to be done by teachers, fewer additional vocabulary words that need to be introduced, fewer outdated or irrelevant terms to be filtered out, etc. More time in the lessons can be spent practicing applying the material to real-life situations.

For the independent learner (especially in a foreign language context), this issue of selecting materials is a huge challenge, and it probably involves a lot of time sorting through potential material. Recognizing that most textbooks are pretty outdated (how many textbooks currently in use never cover the words 手机 or 网络?) is a good start. The big question is then whether or not the material is truly useful for you, the learner. Usually HSK word lists and chengyu stories are not the most useful material. Neither are blindly selected frequency lists. What material is going to get you talking to Chinese people the fastest, about the thingsyou care about, adding to your motivation to keep improving? That’s the right material to study.

Keoni Everington (华武杰) is from the USA and is currently the web and marketing director for The World of Chinese magazine in Beijing, China. He has over 20 years of experience learning Mandarin through study at various universities and long stints in Beijing, Shanghai, and Taipei.

Based on my own personal experience learning Mandarin, I found the best way to bridge the gap between textbook/classroom Chinese and real immersion is to live in China for at least one year and using “forced immersion” with native speakers. When I say forced immersion, I mean creating an environment in which you are exposed to the language on a regular basis and establishing friendships and exchanges with local Chinese.

Actually living in China is an important step towards real-life immersion, but in certain settings such as university campuses, hotels, office towers, and tourist areas there are many EFL speakers to interfere with having a pure Mandarin environment.

There are many aspects of living in China that can aid in language immersion that I took advantage of such as chatting with taxi drivers, haggling at the market, watching Chinese TV and films, reading Chinese comics, learning Chinese songs, and writing a daily Chinese journal. For now, I’ll just focus on two foundation pillars I used to build my Mandarin with.

The first pillar of my immersion was to establish several weekly one-on-one language exchanges with native speakers, at one point I had five different language partners each week. We would decide to speak about an agreed upon subject for a half hour entirely in Chinese and another half hour entirely in English or perhaps an hour in each language. The key was being able to speak and listen exclusively in Chinese without any English interference during that time.

The second pillar was to make many Chinese friends that understood my language goals or ideally could not speak English at all and spend time hanging out and conversing about everyday subjects that came up naturally. The key was setting the tone early on that we would always speak Chinese together and they eventually would get become habituated to the concept of only speaking Mandarin with me.

—

Mark Rowswell (大山) has been called “the most famous foreigner in China”, where he has worked as media personality and cultural ambassador for over 20 years. Today he is seen more as a cultural ambassador between China and the West. To many people Dashan is a prominent symbol of “East-meets-West”, of finding a common ground between the two cultures.

With language education, it’s important just to get out and start using the language, however limited your abilities, as soon and as much as possible. Language learners tend to spend too much time in class or buried in their textbooks and too little time trying to just use the language any way they can.

I think one of the best things about my Chinese lessons in the early years was that my teachers at U of T stopped using textbooks after the first two years. In my view, textbooks are really only good for a beginner level, to teach you the basics how the language is structured, and it’s important to go beyond that as quickly as possible. By that, I mean starting to learn from materials that are not written specifically for language learners but are the ways people in that language group actually use the language between themselves.

Whether it be starting to read newspapers or very short stories to listening to the radio or even learning songs in a Karaoke, talking to taxi drivers, striking up a conversation with anybody — get out and use the language. These days, with dictionaries and reference materials you can easily access from a smartphone, people who want to learn a foreign language should throw away their textbooks as soon as possible and just throw themselves into the language. Create that language environment if you have to, even if it’s only a virtual environment online.

Niel de la Rouviere has been learning Chinese for almost 6 years. He blogs as Confused Laowai and has created HanziCraft, a next level Chinese character dictionary after doing research into Chinese characters for his Master’s degree.

—

Roddy, who runs Chinese-forums.com, which celebrated its tenth birthday earlier this year. The site covers discussions on many topics related to China and Chinese – textbook choices, recommended authentic materials, studying at Chinese universities, and plenty more.

I think I’d warn against a mindset of “I’m immersed, therefore I’m learning.” We all know people who’ve spent years in what should be a perfect language learning environment, yet somehow fail to make much progress. What do they fail to do?

First I think is a failure to pay attention and absorb. What do people actually say and do in the situations you’re in? Sit near the counter in a fast food place and listen to how people order food, or how the cashiers shout the orders back to the cooks. Stand near the doors on the bus and listen to how people buy their tickets or ask the conductor how to get to wherever. Note how your colleagues greet each other and how age or status affects that. Adopt that language.

It’s kind of remarkable how people can fail to do this. I was in McDonalds once eating with another foreigner, who was complaining about how they never seemed to understand his order for fries and he always had to point at the menu. Somehow he’d never noticed everyone else was asking for 薯条, not the 土豆丝 he was requesting.

Second, they meet their own low standards. “I get by.” “People understand me.” That’s great, and in Chinese it’s no small achievement. But how much repetition and clarification do they need to do. Can they walk into a shop for the first time and ask for an item without pointing and get it first time? What about a longer conversation with someone who isn’t used to talking to them? Are there tell-tale delays in what is normally the smooth back-and-forth of conversation? Watch out for warning signs that your Chinese might not be as good as it could be, and deal with them. Which brings me to…

Third, they ditch the textbooks and teachers, as why would they need them now? But good books and teachers will always be useful to speed your progress through the language. As you become more of an independent learner you might use them more for trouble-shooting and to make sure you aren’t accidentally missing out great chunks of the language – but don’t bin the books.

—

Sara Jaaksola has been living in Guangzhou since 2010 and on her blog Living a Dream in China she offers advice for life, love and language learning in China.

Taking Chinese classes for five years now, feeling like your textbook Chinese isn’t really fit for the life outdoors, is more than common to me. I have two excellent and free ways to tackle this problem.

The first is, watch television. Look for new dramas with plots about the life in modern China, with vocabulary that people in your age and circles uses. By watching TV you learn how Chinese people speak in real situations, not like dialogues in your textbooks. I personally started with dating shows (most well known being 非诚勿扰) as their language is on the easier side, then I continued to series like 裸婚时代. Right now I’m watching 小 爸爸.

The second tip is to get a Weibo, Chinese Twitter, account. New, popular and hip things, words and photos spread quickly on Weibo which makes it a great tool to learn both language and culture. For unknown characters or words, copy the message and read it with Pleco’s Pasteboard Reader for example. Follow users on topics you are interested in, for example I like photography and cats so I follow 照片这样拍 and 大爱猫咪控.

With TV and Weibo you can immerse yourself in Chinese listening, reading and writing no matter where you are.

—

Hi! I’m Steven Daniels, I’ve studied Chinese for years and lived in China even longer. My interests–learning Chinese, Chinese dictionaries, and programming–led me to create Lingomi and 3000 Hanzi.

One thing to remember, structured classes and textbooks should always be viewed as a starting point. Very few people can achieve real immersion using textbooks. They don’t have the scope or the time to teach you everything you need. Textbooks and classrooms provide structure, help you build a solid foundation, and hopefully fill in whatever gaps you have in your language skill set.

To bridge the gap, learners have to encounter Chinese frequently (preferably daily). By encounter Chinese, I mean see it, hear it, speak it, or write it. If you’re outgoing, then talk to friends, co-workers, classmates, or anyone you can find who speaks Chinese. If you like reading, then learn through books, magazines, weibo, etc. If you like hanging out at home, then watch Chinese TV (offline or online).

You can encounter real Chinese no matter what your level is, but remember to set your expectations properly. If you’re a beginner you might only catch the occasional word. That’s normal. And try to enjoy yourself when using Chinese. The more fun you have the easier learning Chinese will feel.

—

Yangyang is the founder and on-camera host of Yoyo Chinese, an online education company that uses simple and clearly-explained videos to teach Chinese to English speakers. A previous Chinese TV show host and Chinese language professor, Yangyang is also one of the most popular online Chinese teachers with more than 5 million Youtube channel views.

Bridging the gap from textbook/classroom Chinese to real immersion is one of the most common problems my students face. Many of them don’t have the opportunity to study in China or to converse with native Chinese speakers and they spend lots of time rehearsing and memorizing how to ask questions in Chinese like “What is your name?” and “Where are you from?”

Often, they only practice hearing one kind of response to these questions, so that when they actually get to ask a real Chinese person, they can’t understand their answers, or the person is speaking too fast for them to catch every word. After studying so hard in a classroom, this problem really catches a lot of students off guard.

I solved the immersion problem for my students by creating a special course in the Yoyo Chinese curriculum called Chinese on the Street. In this lesson series, we interview real Chinese speakers right from the streets of China so students can be exposed to the kind of authentic, non-rehearsed dialogue they will hear in a real Chinese conversation. The people we interview are not asked to slow down or enunciate their speech, so students get a chance to hear different pronunciations and different ways of asking and answering the same question. We offer pinyin and Chinese character subtitles in addition to detailed lecture notes and English translation for students to follow along until they understand every word.

Most of my students say this is their favorite course because it gives them some insight into the real China, they get to see some Chinese culture and become accustomed with how real Chinese people talk. Our students find that after immersing themselves in our Chinese on the Street course they are much more prepared to interact with Chinese people on the spot.

In response to the enthusiasm for Chinese on the Street we are also using the same authentic Chinese dialogues as source materials to teach Chinese in our upcoming Intermediate Conversational Chinese course. In this course, the student watches a Chinese dialogue clip and then I offer clear and concise explanations for each word and phrase of the dialogue. This new format will be coming out in November, so keep an eye out!

Chinese on the Street can be used in conjunction with the Yoyo Chinese curriculum or as supplemental material with any other Chinese study program, you can check it out by visiting www.yoyochinese.com.

—

Chinese Forums – This is the only answer not delivered by an individual, but is instead the collected wisdom of Chinese Forums. The thread can be seen here and contains many interesting ideas and useful insights. I have selected a few to include in this article, mostly dealing with areas not covered by the above answers.

First out, we have some hands-on, concrete advice for what to do by 陆咔思:

- Listen to Chinese-only advanced podcasts from sites like Chinesepod, cslpod, and some relatively easy podcasts for native speakers, and audio books for Chinese children

- Read articles and books written for native speakers on a computer/phone in an annotated way that makes reading them much easier (with http://chinesereaderrevolution.com)

- Read bilingual articles (eg from the New York Times)

- Read translations of books I already read before in English (so I won’t get confused about the content even if I don’t understand the language at some point)

- Watch TV Shows with first with English subtitles (especially for historical shows that use difficult ancient vocabulary), then with Chinese subtitles

- Chat with chinese people via QQ/skype/etc

Second, OneEye’s example of how to approach both real speaking and real writing shows that even if it isn’t effortless, it’s very rewarding:

I picked an easy manga (亂馬1/2) and an easy TV show (智勝鮮師) and worked with them until they actually were easy. With the TV show, I transcribed the entire first episode by hand into a notebook, highlighted words I didn’t know, defined them in the margins, and used it as a textbook. It took a lot of time, but then when I watched the second episode, I understood really well and only had to look things up here and there.

Third, Anonymoose questions the entire question in this way:

I think speaking of a “gap” between textbooks and authentic material is singling out a universal natural phenomenon and regarding it as a problem particular to language learning. What I mean by this, is that any time you embark on something new, there will always be a lot of new stuff to learn, the so-called “gap” than needs bridging. But why single out the gap between textbooks and authentic material? What about the gap between not knowing any Chinese and picking up your first textbook? Or the gap between your first and your second textbook? Or let’s say you practice reading about architecture (from authentic materials) in Chinese. If you then start to read about botany in Chinese, you will also experience a gap.

Although Tysond’s post is too long to quote in it’s entirety, I still think you should read it. He breaks down the problem into speed, vocabulary and contexts and offers several ways of dealing with them. He says this about vocabulary:

Preparing for situations by pre-studying what’s likely to come up. Getting a haircut? Lean about washing, blow drying, cutting, styles, length, etc. Visiting a temple? Learn about temples, religion, Buddha, in advance. I was in a bath-house the other day and didn’t realize in advance that I should probably learn the words regarding to scrape all the skin off my body and apply stinging salt to it afterwards. Painful lesson.

JustinJJ mentions the Chinese Word Extractor and explains the importance of spending some time finding the material most suitable for you. This would have been impossible in another age, but nowadays when many learners have most of their vocabularies in apps or computer programs, it’s possible:

What I find works for me is spending the time to find material that is at my level, whether it is listening material or reading material. To do this I have a big list of every word I have studied in a text file and can use the Chinese Word Extractor to determine what percentage of the words in a given native material I have already studied. If I know the great majority of the words already (i.e. the text is comprehensible), then it is much more ‘fun’ using the material and motivating and my reading speed is much faster so I can get through more material. If a text is at an appropriate level many other words I can work out by context without having to physically learn them, and over time I can up the level. If material is too hard, I find that the time I put in is not as efficient, as I would get distracted too easily and it would be too tiring, so I think it’s worth spending the time to determine if a text is at a good level for you, rather than finding out after being bored 20 pages into a novel.

Finally, Silent points out that this isn’t always a good approach because you might spend too much time looking for texts rather than reading them:

A potential trap in this approach is you spend a lot of time in searching material rather then to actually reading/study. A more efficient approach might be to pick material about a specific (somewhat narrow) subject from one source as often vocabulary and grammar are subject and writer/source specific. Then slowly expand in sources and or subjects. E.g. from your favorite sport specific match reviews you might slowly expand to other sports reviews, broader articles about your favorite sport, sports business, general business etc.

—

That was more than 7000 words on immersion. What should we make of all this? I think there are a couple of common themes:

- You will only learn real-world Chinese by actually encountering real-world Chinese

- Motivation is an important factor for any immersion attempt

- Use various kinds of scaffolding to make the immersion easier

- Textbooks are still useful, but they are just part of what you need

- You don’t need to live in China to immerse, even if it certainly helps

If you like this post, please share it! If you want to read similar posts in the future, please let me know what questions you’re interested in and if you know someone else I should ask!

9 comments

Still thinking about this post…

Incredible to think you got responses from all these folks.

Thought of a few questions I would like to ask the panel:

1) Can you hand write Chinese?

2) If yes, how did you learn?

3) If yes, please post a personal hand writing pic.

Here’s another thought…

Remember your posts and our interchange on recording ourselves… outside of a few in the list above, most I’ve never heard speak Chinese.

While text has its place and value, in the age of youtube and recording audio being as simple as a tap on our mobile device, and the fact that the article is about ‘speaking Chinese’, wouldn’t it be great and so relative if each ‘expert’ posted an audio clip of them spontaneously speaking Chinese with a native Chinese… now that would put some real proof in the pudding and demo their true 汉语水平 and 专家 status…

Good post, but maybe a bit much. I was in scroll free-fall after Benny….

A few personal comments:

1 – What beginners have learned IS of limited use, because…. what has been learned is limited.

2 – Textbook prepare you for the real world as much as cookbooks prepare you for real cooking. YOU still have to make the cookies.

I agree mostly with Adam and Benny. No app, website or teacher is going to magically make you fluent, but nobody likes that answer. Time + effort.

Wow, incredible post–one of the best in the site’s history. So much knowledge and ideas to sift through here. Thank you for this, Olle!

I’ve taken about a year off from Chinese to work on French, but this makes me want to get back in the game.

It is not just Chinese, all 2nd language studies present a rather limited use set of phrases, lexicon, and tools for a foreign language.

If you can’t immerse yourself in a Chinese culture, you really have to find another way to bring today’s Chinese culture to you (You don’t need to know all the historic stuff, just the gossip topic of the day).

I suspect reading and writing Chinese can really divert a lot of time from learning to communicate face-to-face in Chinese. So it is important to stick with the spoken conversational language. Becoming a bookworm won’t cut it.

I mentioned translating western movie titles as an interesting task with the newspaper, but it offers tons of opportunities for you to ask your Chinese friends why the difference and to laugh about the contrast… all while practising your Chinese.

In sum, the best learners of modern Chinese are talkers and listeners, not readers and writers. DON’T be shy, use what you have.

I find that immersion is as much as psychological step as it is a way of studying. To immerse yourself into a Chinese language environment, you necessarily need to immerse yourself into the culture that is associated with it. To accept Chinese language as a part of yourself, as your way of communication, your way or thinking, your way of dreaming, as opposed to a foreign object that you try to understand from outside, but isn’t really yours.

It is difficult to do that, but it is quite easy to predict with our students who will succeed in learning Mandarin up to fluency and who will not by just getting known to them socially. It is not those who study the hardest, but those who are willing to accept a culture as different as China’s (almost another kind of reality) as their own – for at least a certain time period.

Hard to do and not for everyone, but there is no faster and better way to learn Chinese.

That’s the psychological side. The studying side is quite straight forward: do not speak English, do not read English, do not write English. Easy for those few lucky ones who actually dont speak English (and therefore are probably not reading this blog) but much harder for everyone else. To choose the difficult road whenever presented with the choice. It takes a lot of willpower. The only real way around this is by simply placing yourself into an environment where nobody else speaks English. Then the studying aspect of immersion becomes very simple. If you manage to sort out the psychological part chances are you will become fluent in Mandarin quite quickly.