When you first start learning Chinese, it’s like arriving by parachute at night in a foreign country. You land, set up camp and gradually explore your immediate surroundings. As you study more and explore the landscape, you learn enough Chinese to survive.

When you first start learning Chinese, it’s like arriving by parachute at night in a foreign country. You land, set up camp and gradually explore your immediate surroundings. As you study more and explore the landscape, you learn enough Chinese to survive.

Then something strange happens. Urged on by language courses, textbooks and teachers, you identify a mountain peak at the horizon and start walking towards it.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

As you get further from where you landed, the terrain becomes more difficult, then hostile. Progress is agonisingly slow, but with perseverance, you win through and reach the top of the mountain.

Looking back down at the landscape, you realise that you know almost nothing about it. You only know the exact path to this mountain, but if you stray from the path, you’ll be hopelessly lost. In fact, you don’t even know about key areas and landmarks, even though they are much closer to where you landed than where you are now.

The illusion of advanced Chinese learning

This is the illusion of advanced learning. By following a course or textbook series, you learn ever more advanced words and grammar, but your knowledge is extremely narrow.

After doing this for a few semesters, you will be reading texts that are quite advanced, but this is only possible because the textbook authors have prepared you for that specific text, or because they have written the text using exactly the words you already know.

If you were to read anything outside your textbook at a similar level, the illusion would shatter, and you’d find that you don’t understand anything.

When your certificate says “advanced”, but you can’t use the language

I have encountered this illusion not only as a student, but also as a teacher and coach when helping frustrated students. You might not have encountered it in exactly the way described here, but the problem is common enough to warrant an in-depth discussion.

It’s common to encounter students who have passed advanced levels of HSK but can’t use the language to communicate or say that they finished textbook number five in a certain series yet can’t read even basic texts about topics not covered there. If you find yourself in this situation, you might want to check out: Why your Chinese isn’t as good as you think it ought to be

A two-dimensional map of your Chinese journey

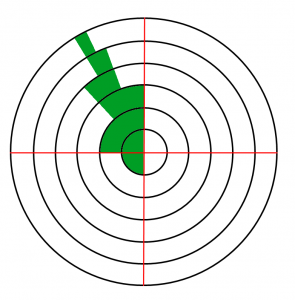

This is what your knowledge will look like if you stick with a typical curriculum. Green represents familiar territory.

In the two-dimensional model of learning described above, you can define a position by how close it is to your camp and in which direction:

- Distance from your camp represents difficulty, so things close to your base camp are commonly used and relatively easy, whereas things far away are more specialised and comparatively hard.

- Direction represents different areas of the language. For example, there are many areas of the language that are of similar frequency and difficulty, so these would be arranged in a circle with your starting point in the middle. If you take the topics covered in your intermediate textbook, they represent language at a similar distance from the centre but spread out in different directions.

One feature of this model is that the area within a certain range from your starting point grows exponentially with distance from the centre. In other words, there’s only one way to know nothing (you just landed) and only a few ways to be a beginner (you can only explore your vicinity in so many ways), but then as you leave the beginner stage of learning, the paths you can take multiply rapidly.

This analogy would work even better with a sphere or even a hypersphere, but these are harder to illustrate and less intuitive. Let’s stick with a two-dimensional map!

Courses, textbooks and teachers create the illusion

The illusion of advanced learning is mostly created by formal learning resources, such as courses and textbooks, and to a lesser extent teachers shaped by the education system.

While this might sound outrageous, it’s common that progress is measured by how many chapters students have “finished” in a certain amount of time. Sometimes, there are even rules for how quickly students should progress through a textbook series.

While it might make practical sense to organise teaching like this, what matters is of course what students learn, not how many pages they’ve flipped through in their textbooks. Even things like are related to the language, such as superficial knowledge of vocabulary, is a bad proxy for communicative ability.

The combination of measuring the wrong things and hurrying through fundamental aspects of the language is what creates the illusion. Some students create it on their own, but most are encouraged by the system in which they study.

Bridging the gap to real-world Chinese

One effect of the illusion is that it can be painful and discouraging when it shatters. If you think you’re an advanced learner because you reached book five or because you learnt all the vocabulary to HSK 6, you’re wrong, but you might not know it yet if you’ve mostly stayed in your classroom.

For advice about bridging the gap to real-world Chinese, check this article where I asked more than twenty teachers and students with cumulative centuries of experience: Asking the experts: How to bridge the gap to real Chinese.

This is only a problem because courses are often more about superficial progress than real progress. If it can be shown that students are able to finish a certain HSK level after so and so many months, and that they reach book four after only two semesters, that makes the school look awesome, but that relies on the assumption that the right things are being measured, which almost certainly isn’t the case.

Thus, questions like “Will I be fluent in Chinese if I finish this textbook series?” or “How good will my Chinese be if I finish book four?” are meaningless. Like I said earlier, it’s not flipping through pages in a book that enables you to use the language to communicate.

Thus, the illusion of advanced learning is only a problem if believe in it and stay within the safe confines of your textbook. This means you study gradually more difficult material, but neglect easier things you should actually learn first.

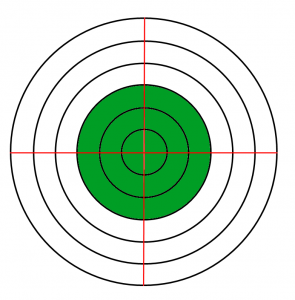

This is what you want your knowledge to look like instead. You can then choose specific directions to focus more on, but you need a solid foundation before you do that.

What to do instead: Avoiding the illusion of advanced Chinese learning

The solution to the problem is simple. Instead of trying to get as far as possible in a textbook series, strive towards broadening your knowledge.

This typically means you should learn many easier things rather than a few hard ones.

Here are a few examples:

- Use the language outside the classroom – By definition, you use the language at your current level, so the things you want to say and need to say in conversations are also the things you should learn. You might occasionally need to say things that are too advanced for you, but communicating is still the best way of spotting areas you need to focus on more. This the only way to really master the basics.

Use more than one textbook – Instead of studying the next chapter in your textbook, get another textbook and study that in parallel. This will give you a broader base. You can do this with more than two textbooks if you want. Different authors choose different topics, without making the language more difficult.

Use more than one textbook – Instead of studying the next chapter in your textbook, get another textbook and study that in parallel. This will give you a broader base. You can do this with more than two textbooks if you want. Different authors choose different topics, without making the language more difficult. Use graded readers and other reading materials – Graded readers are awesome because they are long compared to textbook chapters. For example, each volume in the first level of Mandarin Companion contains almost ten thousand characters, but you still only need around three hundred unique characters to read the texts. If you read all the book (currently eight), you can read almost 80,000 characters at the same difficulty level before you move on. Your textbook only contains a small fraction of this!

Use graded readers and other reading materials – Graded readers are awesome because they are long compared to textbook chapters. For example, each volume in the first level of Mandarin Companion contains almost ten thousand characters, but you still only need around three hundred unique characters to read the texts. If you read all the book (currently eight), you can read almost 80,000 characters at the same difficulty level before you move on. Your textbook only contains a small fraction of this! Use podcasts and other listening content – Most podcasts are non-sequential, meaning that they don’t count on you having listened to earlier episodes before you listen to later ones. This will shatter the illusion of advanced learning immediately. Naturally, try to avoid podcasts that are mostly in English if you want to improve your listening ability.

Use podcasts and other listening content – Most podcasts are non-sequential, meaning that they don’t count on you having listened to earlier episodes before you listen to later ones. This will shatter the illusion of advanced learning immediately. Naturally, try to avoid podcasts that are mostly in English if you want to improve your listening ability. Use frequency lists – A wonderful way to plug holes in your vocabulary is to use frequency lists. This means that when you reach the intermediate level, you use a beginner level word list to make sure you know all those words. When you reach an advanced level, you check the intermediate lists. Be careful when using lists as a source of new language, though: Should you learn Chinese vocabulary from lists?

Use frequency lists – A wonderful way to plug holes in your vocabulary is to use frequency lists. This means that when you reach the intermediate level, you use a beginner level word list to make sure you know all those words. When you reach an advanced level, you check the intermediate lists. Be careful when using lists as a source of new language, though: Should you learn Chinese vocabulary from lists?

Conclusion: Seeing through the illusion of advanced Chinese learning

Having finished a certain textbook says nothing about how good your Chinese is, and even a certificate with the word “advanced” or similar means little. It’s possible to achieve both by focusing on exactly the right things, which will create the illusion of advanced learning.

I’ve met students who ought to be advanced on paper, but who struggle even with basic conversations. I’ve also met students who struggle with proficiency tests and don’t care about textbooks but are still great at communicating in Chinese.

You only want to be in the first group if you really care about your grades. Naturally, the two groups are not mutually exclusive, you can get good grades and be good at communicating, but don’t make the mistake of thinking that they are the same thing!

If you really do care about your grades, I’ve written more about how to get better grades here:

Editor’s note: This article, originally published in 2015, was rewritten from scratch and massively updated in June, 2023.