Vocabulary acquisition is both one of the most important and interesting areas of language learning. In order to understand spoken and written Chinese, we need to understand a large number of words. We obviously need words to speak and write, too, but not anywhere near as many.

Vocabulary acquisition is both one of the most important and interesting areas of language learning. In order to understand spoken and written Chinese, we need to understand a large number of words. We obviously need words to speak and write, too, but not anywhere near as many.

Of course, you need more than words, but few other areas are as important for your ability to function in a language. Or, as David Wilkins (1972) put it:

Without grammar, very little can be conveyed, without vocabulary, nothing can be conveyed.

Let’s expand this. Once you have learnt basic grammar (such as basic word order), the utility of investing more time in learning grammar decreases rapidly, but the case for expanding your vocabulary doesn’t weaken until you reach an advanced level, and maybe not even then.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to this article:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many more!

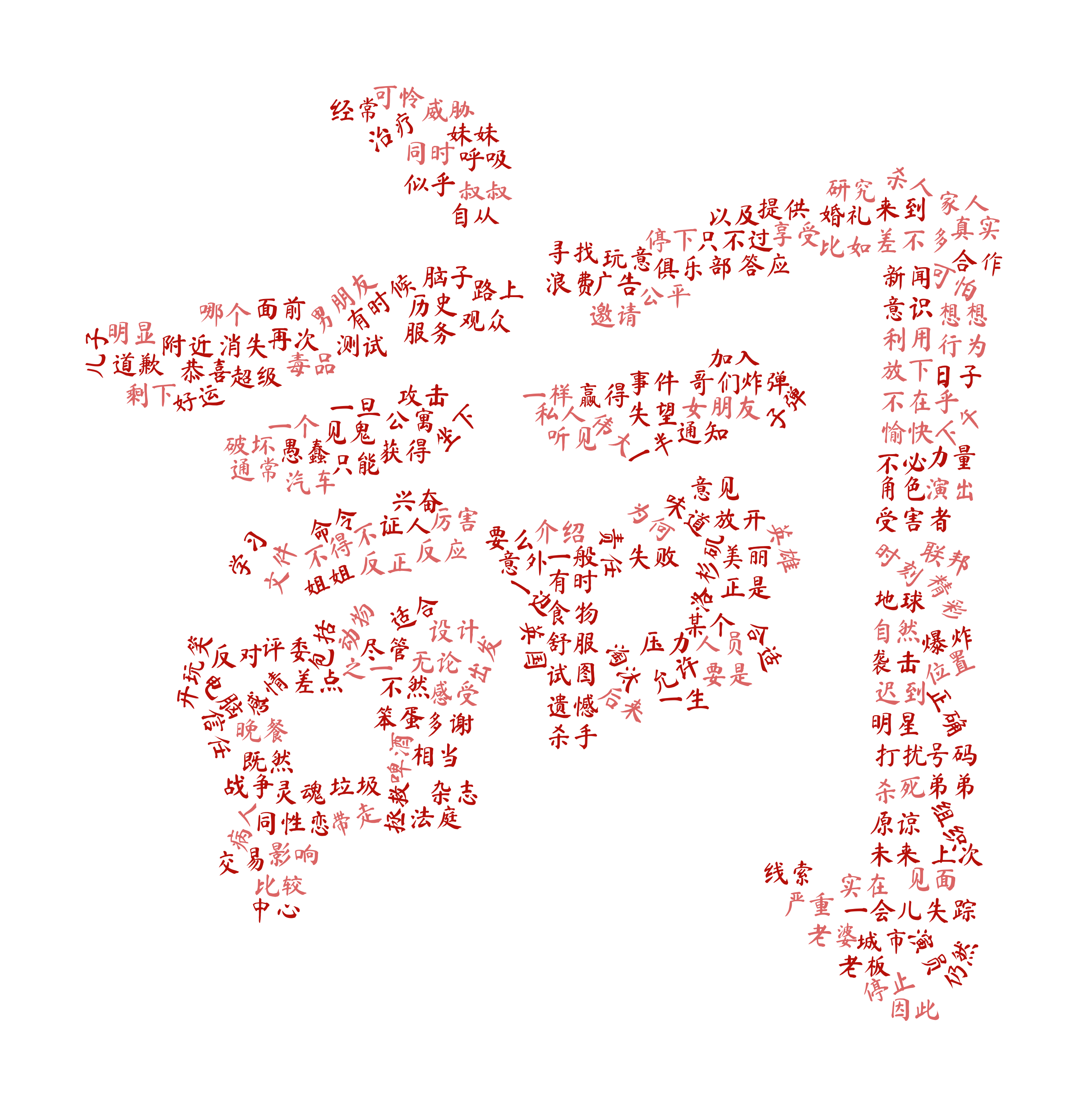

Learning words in Chinese: When quantity beats quality

I think vocabulary is not merely king, but god emperor of the language learning universe. I have spent thousands of hours explicitly learning and reviewing words in Chinese. I have mostly stressed quantity over quality, that is, I prefer to learn an additional 1,000 words passively (i.e. only being able to recognise and understand) over learning 100 new words actively (i.e. so I can use them in my own speaking and writing). With this approach, I added roughly 25,000 characters and words to Anki over my first five years of learning.

In this article, I will explain why I put such an emphasis on vocabulary. I will also share some thoughts on how I would changed my approach with the wisdom of hindsight and having spent more than a decade learning and teaching Chinese.

The focus of this article is not to talk about how to learn words in Chinese. There are already many articles about that here on Hacking Chinese, all collected here:

The benefits of knowing many words

Knowing many words is good for many reasons:

- It increases your listening and reading comprehension. While you obviously need more than just words to be successful at either, not knowing key vocabulary is likely the most common reason why students fail to understand something in Chinese.

- It increases your chances of being understood both when speaking and writing. While you will still struggle with getting more subtle points across, having a broad vocabulary makes it much more likely that Chinese people understand you, even if your grammar is halting.

-

It accelerates your learning in general. Since understanding plays an important role in learning, it means that the more you understand, the more likely you are to learn the bits you didn’t understand. This is the basic principle of comprehension-based learning and teaching.

Out of these, the third reason is the most interesting, not because the other two are less important, but because they are quite obvious. Vocabulary as an accelerator for your learning in general merits a more in-depth discussion, however.

Vocabulary as a stepping stone to more listening and reading

I’m generally in favour of learning and teaching methods heavy on input (listening and reading). I think many things that are explicitly taught are maybe best learnt simply by listening and reading more.

I’m not of the opinion that speaking and writing are not also essential parts of learning, I just think they should be preceded by listening and reading.

I don’t mean you should spend months and years just absorbing the language, but rather that it’s a good idea to have heard or seen a word in context multiple times before learning how to use it. Too many teachers introduce new words in class, and then expect students to use them in their own sentences five minutes later.

Passive vocabulary as scaffolding

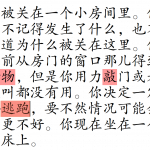

The problem with listening and reading in Chinese is that you can’t just dive in. Reading even simple stories requires you know hundreds of characters and words, and if you don’t, you won’t learn much from the experience (although you’ll get really good at using your dictionary app). Listening is similarly difficult as a beginner.

The ideal solution to this problem is listening and reading tailored to your level, which includes enough of what you already know to allow you to learn what’s new. A learning environment rich in context further adds value.

Unfortunately, this method of learning is open almost exclusively to newborn children in their first language. Most people who learn Chinese as adults don’t want to or can’t afford to have a native speaker following them around all day, talking to them in level-adjusted Chinese. You can and should get that kind of input as much as you can, but it’s unlikely to be enough.

The next best thing is listening and reading to Chinese which isn’t individually tailored to you, but still suitable for people like you in general. This includes graded readers, textbooks, podcasts, courses and so on. To make it easier, you can use various kinds of scaffolding:

The endless ocean of unfamiliar words

This is where learning Chinese can be very frustrating. It seems that no matter what level you’re at, there will always be more words to learn. It just never ends! I can tell you that it does, but probably later than you think. HSK6 only covers 5,000 words after all, which won’t take you very far in newspapers, literature or any other material written for adult native speakers.

Without a broad vocabulary, you are severely limited in what kind of content you can listen to and read. Most beginner and some intermediate students say that they can only understand what their teacher is saying and what’s in their textbook, but as soon as they move outside of this comfort zone, they understand almost nothing.

One of the main reasons this happens is that many students, teachers and courses spend all their energy on just a few words. The time is used on a few texts in one book and the words contained therein. Too much time is spent going through these in depth, discussing finer nuances of words the students have no real grasp of yet. The next textbook builds on exactly the vocabulary you learnt in the previous book, giving rise to an illusion of advanced learning.

If your goal is to speak and write right now, it’s true that you really need to know the words well (as I argued in last week’s article), but this is only true for the core vocabulary. The more you learn, the bigger that core vocabulary needs to be, but beyond that, you need a passive vocabulary many times the size of your active vocabulary.

One of the most serious flaws in the way most courses are structured is that the emphasis is almost entirely on building active vocabulary.

Why passive vocabulary is so desirable

Now, you might think that active vocabulary is certainly better than passive vocabulary. I mean, isn’t it good to also be able to use the words?

It is, but at what cost?

The problem is that it’s very inefficient to force vocabulary from completely unknown to being part of your active vocabulary. Like I said earlier, having heard and seen the word many times in context before trying to figure out how to use it yourself will make it easier.

Adding a word to your active vocabulary also takes more time, especially in Chinese. You need to learn how to write the characters (as opposed to just recognising them), you need to know what functions the word can have in a sentence (rather than hearing someone else use the word in a certain way), and you need to figure out which words normally go together with the word you’re learning (rather than learning this by being exposed to such combinations over time).

A question of efficiency

The bottom line is that if your goal is an approximate understanding of a word in spoken or written Chinese, you can learn many times more words in the same time it would take you learn a single word really well.

So, the question is not if you prefer to add a word to your active vocabulary or your passive, but if you prefer to add one word to your active vocabulary or ten to your passive. You only have so much time at your disposal, so choosing to spend more time on one thing means spending less on something else. Efficiency matters.

The 25,000 characters and words I learnt during my first five years of learning were of course not all in my active vocabulary. I mostly focused on learning to understand these words, mainly in writing. In hindsight, I would have benefited from using audio flashcards as well, which is free and easy to set up in Anki. I did not try to learn how to use all of them, that came later, either naturally (they just come out, feeling right) or through targeted practice when needed.

Vocabulary: A stepping stone, not a goal in itself

Learning many words is not the end goal, of course. The idea is to learn many words so that you can then understand more spoken and written Chinese, which will gradually build your knowledge of how these words are used, which in turn will enable you to speak and write as well. That means that this strategy of pursuing a large passive vocabulary is madness without very large amounts of input.

Just to be clear here, I don’t mean that you should learn your first few hundred characters in your course textbook, then pick up a graded reader at that level and then move on, I mean that you should read all the graded readers you can find at your level.

Mandarin Companion currently has eight books at the 300 character level, and there are more series of graded readers too. Each book contains a little under 10,000 characters; your whole textbook probably contains less than that. The same argument can be made for listening, of course.

Conclusion

Looking back at my own learning, I think I did the right thing, putting such a heavy emphasis on vocabulary. However, I regret that I spent too much time listening to and reading Chinese that was actually quite difficult. I struggled my way through books, radio programs and news articles much above my level, too early.

Instead of reading one page of difficult Chinese, I could have read ten or twenty easy pages. That would have done more for my Chinese and would also have been more pleasant. To put it briefly, I should have focused much more on extensive reading and listening. And so should you. But to gain access to more reading and listening, you really do need to know many words.

Editor’s note: This article, originally from 2010, was rewritten from scratch in May 2020.

26 comments

How do you define learning a vocabulary item? Because I feel like your definition might be different mine and other people’s.

I’m not sure that it matters in this case? I think knowing many words is important regardless of how you define “word” or “know”. As you can see from the article, I think learning many words (to a lesser depth) is better than learning fewer words (to a greater depth), at least in the beginning.

Wow. Amazing articles. These tips of yours are gold.

Thank you!! Keep it up the fantastic work ! 🙂

so could you please give me some websites or tools to improve my chinese vocabs, i can read easy chinese articles on the chinese newspaper but still can’t read the news

Just read more and look up words that occur frequently (but don’t learn every single new word you encounter). If you have problems finding good things to read, you can try graded readers or bilingual news such as BBC or New York Times.

Do 成语s count as words?

Some 成语 make little sense even if you know each character. Many 成语 also contain characters you would rarely find in other words but frequently in one or several 成语 which in turn might be used quite freuqently. Some 成语 are used so frequently they should be learnt in the same way as learning high frequency words. I think this is where advanced learners should perhaps focus a lot of systematic effort.

Apologies if this was already mentioned in the discussion above. I could not immediately see it.

I think 成語 can be considered as vocabulary units just like any other words. However, most 成語 are much rarer than teachers seem to think and I personally believe that learning to use lots of 成語 is a waste of time. Understand them? Yes. Learn to use them? Not really. I wrote more about this here.

I couldn’t agree more. Relating this to English, I know people who have studied English for decades who have lived in the US for a decade who easily get lost due to lack of specific vocabulary. This usually consists of specific types of objects or things.

For example, they know what a bird is but they don’t know what a robin is. Or they know the 3 most common types of dogs, but not the next 20 most common types. So, when someone says, “I had to put down my malamute,” they are instantly clueless.

In general, I think your vocabulary needs to be WAY larger than most people think. For Chinese, I’ve found it useful to create (deep) Anki lists of words organized by either type (e.g., dog breeds, spices, birds, etc) or domain (car parts, furniture, etc). This doesn’t mean you learn every obscure type of dog in Chinese, but you learn the 15-20 breeds that come up 98% of the time whenever dogs are discussed. This helped improve my comprehension enormously.

I believe that this is not an issue of a foreign language learner. I feel most people in the US who are native English speakers find themselves drowning in unknown vocabulary from time to time. They have found strategies to avoid words they are unfamiliar with or do not understand.

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/11/141112120208.htm interesting research .

This is an older post but I liked it so I hope you don’t mind me commenting.

I completely agree with you that vocabulary is king. I very rarely encounter situations where I can’t understand due to grammar and many where the fault was with lack of vocabulary. For most languages I’ve studied I could master the core grammar in less than a month and so 99% of my actual study time was in learning new vocabulary.

I also agree with you about quantity over quality when it comes to listening and reading. My one disagreement with this would be when it comes to speaking. I’ve seen lots of language students with relatively large passive vocabularies that can barely say Hello. Taking vocabulary to the level of smooth conversational usage takes a lot more time and effort then just passive understanding. Therefore for the core words that you need to start conversations I would say quality trumps quantity, particularly when just starting out.

It’s perfectly okay to comment on old posts! I wouldn’t have written this article in this way if I rewrote it today, but the general argument is still true, I think. I would say that quality and quality are related to passive and active vocabulary, but they are not the same. I think that having a large, passive vocabulary is often better than having a very small active vocabulary. However, it goes without saying that having a large passive vocabulary AND an active smaller vocabulary is better than either. I think the kind of imbalance that you mention comes from not ever really using the language. I’ve found that the most common words get used so often in conversations that they seldom need to be studied in addition to this. So, I would say that the main problem for students like those you mention is that they don’t use the language (at all?), not how they learn vocabulary in particular, although that’s certainly part of it!

keep up the good work i realy enjoyed reading every word of your piece and would love to read more

Thank you for your great post! I agree, concentrating on passive vocabulary is vital, although I only learn comparatively simple languages like French and Italian (as a German native speaker). I want to add another reason. Even in our mother tongue, the relation between active and passive vocabulary is approximately 1:1000 (Mario Wandruszka in the book ‘Die Mehrsprachigkeit des Menschen’. Of course, this differs from person to person, but the general idea is clear. So it is unfortunate that our children are forced to use inefficient language learning methods in school.

I came across your article a year ago and it was a life changing moment for my language learning. I studied Korean for two years without much progress because I focused more on mastering its complex grammar than learning words. I switched to Chinese for its relatively simple grammar and spent the last twelve months mostly swiping through audio flashcards and learning HSK1-5 words. To my surprise, my reading and listening comprehension has improved significantly to the point where I can now have conversations with ChatGPT in Chinese and understand most of it. So for that, THANK YOU SO MUCH. I intend to keep learning words to HSK9 – I’m curious what I will be capable of doing then 🙂

Glad to hear from you and even happier to hear that the approach worked out for you! I think the problem is that most people don’t realise that grammar is mostly learnt implicitly and that there’s only so much you can do by studying it explicitly. The only way you can learn grammar implicitly is by understanding things you’re reading or listening to, thus being continuously exposed to grammar in context. If you don’t know lots of words, this will be very hard, or almost impossible, to achieve. Extensive reading and listening works better (both in the sense of it being more efficient and in the sense of it being more practical) the more you can understand, and that understanding relies mostly on vocabulary. If I were to add one piece of advice, it would be to expand your vocabulary by reading and listening, rather than by learning the words first and then using that to read and listen more.