How important are tones, really? They are an integral part of Chinese, we all know that, but do you actually need them all the time? In this article, I will talk about tones, why they are important and some problems students encounter and how to solve them. There are of course much, much more to say about tones, but this week’s article will focus on attitude rather than practical or theoretical matters directly related to tones.

Just how important are the tones anyway?

Occasionally, I hear people say something along the lines of “tones aren’t important in Chinese, if I just achieve some fluency and talk really fast everything will be okay, the natives don’t use tones in natural speech anyway”. This is not only wrong, it’s an extremely dangerous attitude to have as a beginner if you ever hope to learn Chinese properly.

It is true that you will be able to order a beer, say hello, I’m from America or apologise without worrying about tones, especially if you’re talking with native speakers who are used to foreigners. This is because it doesn’t really matter what you say, they see you, a foreigner, in a certain situation and they immediately know that the number of things you’re likely to say is limited and it’s only a matter of deciding which of the possible phrases you’re trying to say. It doesn’t matter how much you botch the tones, you’ll get your beer.

However, if the person you’re talking to can’t guess what you want to say, communication will rapidly break down if your tones are off. Next time you take a cab somewhere, try to get to the correct destination with the wrong tones (here is a hint: it doesn’t work very well). When you have left the beginner level you will also start expressing ideas which aren’t immediately obvious to the listener and you may use words they don’t expect. If you don’t get the tones right, it is likely that people won’t understand what you say.

Read more here: The importance of tones is inversely proportional to the predictability of what you say

That being said, it’s true that native speakers don’t enunciate every singe tone very clearly when they talk rapidly. Some tones are reduced and only stressed syllables retain their tones completely. However, this is not the same as saying that you can do the same thing. It means that it’s even more important to get those key tones right. See this article on Sinosplice.com for more about this.

Tones aren’t just marks added above a vowel

When we start learning Chinese, it’s easy to think of tones as something that is added to an otherwise independent syllable. It’s easier for us to remember and distinguish the between “mí” and “má” (same tone, different vowel) than between “mí” and “mì” (same vowel, different tone). This is natural because it’s likely that our native language doesn’t use tones in this way. We need to focus on this explicitly to understand that the tone is an integrated part of a word as much as the vowel is.

Research has shown that tones in Chinese are as important as vowels (i.e. they carry as much meaning as vowels do). This is easy to understand theoretically, but I personally still think it’s hard to feel intuitively.

Don’t cheat with tones

A lack of understanding leads to a situation where we tend to focus more on the sound of word (as opposed to the tone). It’s easy to remember that it should be “zhen”, but is it “zhén” or “zhèn”? If you’re using spaced repetition software (which you should), have you ever answered that you know a word even though perhaps one tone is off? Would you do the same if you replaced “zh” with “z”? Or if you thought it should be “i” instead of “e”? I’m not saying everybody is doing this, but I think lots of people are and it’s not good. If you don’t know the tone, you simply don’t know how to pronounce the word. Cheating with tones is easy, but the only loser in the long run is yourself.

How to learn tones

The main reason for not cheating with tones and focusing on them from the very start is that it’s very hard to change incorrect tones later. The earlier you start correcting your mistakes, the easier it becomes. Of course, if you want to improve your tones, you first need to know what problems you have. One way of doing it is using the method I have suggested in another article, which works very well even if you don’t have access to a qualified teacher (you just need any native speaker). If you’re having problems with the third tone, you might also be interested in reading this article about learning the third tone.

How to remember tones

If we want to remember tones, the first thing we need to do is start treating them like they are integrated parts of the words we’re learning, rather than something extra added on top. If you don’t know the tone, you don’t know the word and need to review it again; cheating here will only make it even harder next time. Here are some other things you can try:

- Always read words aloud when you review

- Always write tone marks (and read aloud)

- Pay attention to tones you hear (repeat in your head)

- Associate tones with other characters with the same tone (if you remember that 第二次世界大战 only consists of fourth tones, you can use this to remember that all individual characters are fourth tones; create new words or phrases for particularly tricky characters/words)

- Use colours (automatic in many programs, i.e. blue for fourth tone, red for first etc.) then try creating mnemonics based on the colours (think of an egg painted blue for 蛋 or a red chicken for 鸡); this approach will be tricky to use on thousands of words, but I use it for tones that just refuse to stick

Focusing on pronunciation as a beginner

I usually advocate not focusing too much on details in the beginning, simply because I think it’s not very helpful to learn the exact definitions of words or the difference between two very similar grammar patterns until a more advanced level. Pronunciation, however, is an exception. It’s fairly easy to adjust one’s vocabulary, but it’s a lot harder to change one’s tones. If we hope to reach a I high level, pronunciation is something we should always practise diligently, from day one. Paying attention to tones is a good start.

19 comments

Another excellent post!

My teacher have told me that 4th tone is ok, but other tones need more work. Especially the 2nd tone needs improvement and also the 3rd tone when it’s the last character in a word.

After saying this I also have to say that even though my tones aren’t quite correct, usually Chinese people can understand my Chinese when I’m speaking full sentences. When it’s only one word, then I have to be more careful to say the correct tone.

I do want to get better pronunciation and I think that also listening to a lot of material helps with this. I just started watching a Chinese TV series and occasionally watch Chinese movies. I also started reading aloud after a recording (I have Graded Chinese Reader 2 with cd) and I hope it’s going to help with my tones and with my pronunciation with z, zh, c and ch.

Any other tips to improve my pronunciation and tones are welcomed!

@Sara Here are some tips for learning pronunciation:

The introduction of the Integrate Chinese I textbook has really precise explanations on how to pronounce the different initials. For example “To make the zh sound, first curl up the tip of the tongue against the hard palate, then loosen it and let the air squeeze out the channel thus made….” After knowing how the tongue, lips and teeth are supposed to be it’s just a matter of practicing it systematically and slowly until the muscles do it subconsciously. The explanations are a bit technical, but Wikipedia helps a great deal with things like “hard palate, unaspirated, etc…”

As for correcting tones, it’s not so easy to do alone. Basically, as a westerner you can’t go too high when pronouncing the first tone, and can’t go too low for the third. I don’t know any good tips for the second and fourth one, except than trying to exaggerate them. One thing to keep in mind is to keep the amplitude (level of voice) constant, and only change the pitch. This is easier for the voice and makes it sound more natural.

There’s a program called Speak Good Chinese which was developed to help correct the tones. It’s very unforgiving and so very rewarding when you manage to get the tones right consistently. It can be found here: http://speakgoodchinese.org/

“It’s easy to remember that it should be ‘zhen'”

Says you. I mix up the zh/ch sounds all of the time (it’s just a difference of voicing, after all). I am even guilty of saying that I know the card in Anki if I thought it was a zh and it’s actually a ch (and vice versa), though I know that I shouldn’t. That said, I think getting zh/ch correct is not important as getting the correct tone, at least in my experience in trying to communicate with people. Likewise, I would say that speaking English getting the stress and stress-timing right is more important than mastering the þ or ð – if someone botches the stress/stress-timing, it makes it significantly more challenging for me to understand them, whereas I rarely have trouble understanding someone just because they are botching þ/ð.

Totally agree. I’d even go as far as to say that tones are more important than the consonant and vowel sounds. You can be a bit inaccurate with those and still get away with it, but wrong tones do just throw people right off.

I remember once reading on All Japanese All the Time that Khatz doesn’t fail cards for which he gets the tone wrong, but gives them the lowest successful rating. This has been my approach; with Anki I mark it as a ‘2’ if I miss one tone, and fail it if I get more than one tone wrong. I might be doing some harm in the long run, but I would just be failing too many cards for which I otherwise know all the other information (meaning, recognition, pronunciation aside from tone). How do you all handle it?

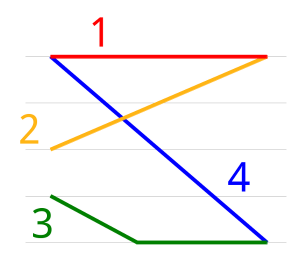

Intuitively, I handle it the same way you do, but I don’t think its advisable. I’m not saying that your approach (or Khatzumoto’s) is wrong, but consider that tones are as important as (if not more important than) vowels. Consider the following four mistakes:

1) Answering “shen” instead of “shan”

2) Answering “shén” instead of “shèn”

3) Answering “wu” instead of “wo”

4) Answering “wú” instead of “wù”

I think you should answer all of these the same way (i.e. either all “fail”, which is what I would do, or all “hard”). If you’re okay with missing 1 and 3, you might be okay with missing 2 and 4 as well. However, my guess is that most people aren’t okay with missing 1 and 3, but feel it’s okay to miss 2 and 4. In my opinion, this is native language bias. We don’t feel that the tones are as important as the vowels, so we don’t study accordingly.

@Sara K. : zh/ch is not really a difference of voicing (in my opinion there’s a slight difference of voicing but that’s not what any book would say) but of aspiration.

Other than that, I agree with the article, particularly “read aloud when you review” and colours. However, I hate the choice of colours automatically set for me. I personally go with 2nd blue 4th red because in my mind they are opposite (and 4th sounds like a negative command), 1st green as it’s “peaceful” and 3rd purple because it’s red+blue (4th + 2nd, in a way..) and I need a colour that has a good contrast.

The good thing with colours is that there’s always this moment when I see a character and my visual memory would remind me that it’s red, hence 4th tone.

You’re right – the difference between zh and ch is mainly one of aspiration, not voice (at least according to Wikipedia, which is not necessarily authoritative).

Anyway, while I generally find it easier to remember the position of the tongue than the tone (for example, I find it easy to remember that something should be a ‘g/k’ and not a ‘b/p’), I actually find it more difficult to remember the correct voicing/aspiration than the correct tone. Getting the voicing or aspiration right is not as important as getting the tone right (at least if the goal is communication) … but it’s still annoying.

These sounds can be easily mastered using phonetics. If the IPA and “vocal tract” aren’t things that you’re intimately familiar with yet, you’re really missing out.

I have a really important question here – how do I input the tones using my normal keyboard? I’m doing the flashcards for Anki right now and I want to write full tones, not the system with syllabe+number, that indicates tones. Thanks!

In Anki: Install Chinese support.

In general: Use this website.

Anyone who tries to say tones are not important, on the grounds that native speakers often minimize them, especially in rapid speech, should think about hand motions in sign language. Expert signers, especially those deaf from birth, often use hand motions so slight that most outsiders can hardly tell what the motions are at all let alone recognize the sign. But they are moving their hands! Rather than conclude that hand motion is irrelevant to sign language, you should conclude that expert users can recognize cues from one another than the less expert do not recognize.

I have spent three weeks learning tones, and the other three came pretty quickly, but even after speaking with natives, practicing pitch in singing lessons, and practicing for weeks, I have made absolutely zero progress on the third tone. What people like me need is a video explaining how the human body makes that tone…including muscles in the throat, body cavities and resonators, etc., so that we can learn HOW to make that sound…physically. Simply listening to it over and over and over and trying to say it over and over and over doesn’t help some of us.

I can’t make a video, at least not right now, but perhaps this article helps. The third tone is usually gravely misunderstood by students, mostly because it’s badly taught:

Learning the third tone in Chinese