Having studied a significant amount of phonology and phonetics, as well as focusing my research more and more into pronunciation instruction, the question of so called fossilisation has popped up regularly. It has also been bothering me for a long time.

What fossilisation is and what it is not

In short, fossilisation means that the learner stops improving in a certain area, usually pronunciation (that’s what I’m going to talk about here anyway, but similar arguments can be made for other skills). The facts are quite indisputable: almost all native speakers learn the pronunciation of their native language to functional perfection, most adult foreigner don’t, even after many, many years. Thus, there is a period after which adults seem to stop learning and this is called fossilisation. This effect is often attributed to the fact that most adult students perpetuate bad pronunciation habits (errors) which will then be (allegedly) impossible to change.

Why I don’t like the term fossilisation

There are two things that bother me here. First, it feels like people use the term fossilisation not only to explain, but also to excuse bad pronunciation, saying that it’s natural, common and not something to feel bad about. I mean, if every adult learner is bound to stagnate at a certain level, why bother teaching pronunciation to advanced learners? This is often regarded as an absolute truth, producing statements like “you can’t reach native-like pronunciation after the critical age” (the definition of which depends on who’s talking).

This is nonsense. I have taught a significant number of adult students, both as a teacher and as a graduate students. I have so far never encountered someone who can’t improve. I would be very happy if people stopped throwing the word around as some kind of explanation for why foreigners fail to acquire proper tones or whatever. It’s a description and a name for an observed fact and has (almost) no explanatory value at all.

Diminished returns, not fossilisation

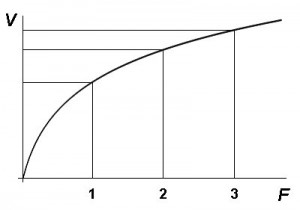

If the concept of fossilisation is bunk, we need an alternative way of explaining the fact that many foreigners have severe problems with their pronunciation and is nowhere close to near-native in their Chinese even after many years. I think the answer lies in the infamous principle of diminished returns.

Put very briefly, the better your pronunciation gets, the more time you need to make a significant improvement. I might be able to help a beginner to make huge leaps forward in just a few hours, but if I’m going to improve my own pronunciation in any noticeable way, it requires long and concentrated effort. It’s also the case that improving your pronunciation from “very bad” to just “bad” help your communication abilities tremendously, but levelling up from “quite good” to “very good” actually doesn’t help that much.

Another way to look at fossilisation looks like this: The problem with pronunciation is that the more times we make a certain error (failing to pronounce the third tone as a low ton in front of first, second and fourth tones, for instance), the harder it becomes to change that habit later. However, even if this is true to some extent, that doesn’t mean that it’s a law of nature you can’t bypass. Changing pronunciation isn’t necessarily easy, but it can definitely be done.

Why we stop improving your pronunciation

In essence, I’m convinced that the reason most foreigners have lousy pronunciation isn’t because they started learning Chinese as adults or because it’s impossible to learn as an adult. Instead, it’s because most students simply aren’t motivated enough to put in the effort it requires. This is similar to the argument I made in the article about adult vs. child learning (You might be too lazy to learn Chinese, but you’re not too old). Changing pronunciation habits is hard, why not do something more useful instead when people seem to understand what you say most of the time anyway? Still, remember that bad pronunciation always interferes with communication.

I can come up with several other reasons:

- You don’t have time

- You don’t know what to improve

- You don’t know how to practice

- You think it’s boring

- You’re too lazy

I’m not saying that it’s equally easy to learn pronunciation as an adult compared to as a a child, nothing could be further from the truth, but I am saying that just because you won’t acquire good pronunciation automatically it doesn’t mean that it’s impossible. This article is about adult pronunciation, child acquisition of pronunciation is something completely different.

What to do if you actually want to improve your pronunciation

You need to solve the above problems, roughly in the order mentioned above. Most importantly, you need to know what your problems are and how to fix them. To do this, you need feedback from a teacher. Obviously, you also need to listen a lot and mimic a lot, but without feedback, you stand little or no chance of improving (think of it like this, if you could improve only by listening and mimicking, your Chinese would be excellent by now).

Most teachers can offer you feedback and corrections, some teachers can explain what you should do instead, a few can help you design a plan to overcome you current pronunciation problems. If you’re very ambitious, you can do most of these things on your own with occasional support. The important thing is that you can do it if you really want to. I’m not going to argue that you should, that’s up to you.

21 comments

I agree completely that fossilization is often used as a bad excuse for poor pronunciation. But at the same time I believe there are changes that take place in the brain as one ages that make it harder to achieve native like pronunciation. Children don’t put in conscious focused effort and yet absorb the sounds and rhythms of their mother tongues perfectly. A second language learner can put in years of focused concentrated effort into their pronunciation and although they may have very good pronunciation for a non native speaker there will still be something about the way they speak that allows them to be identified as a non native speaker.

I think everyone no matter how old can achieve understandable and good enough pronunciation. However is it possible to achieve near native like pronunciation without starting very young?

Learning pronunciation as a child is completely different from learning pronunciation as an adult, but since this article isn’t about children or first language acquisition, I didn’t include anything about that. Still, I agree that the article isn’t really complete without it, so I added a short paragraph about it. In short, I agree with you.

Regarding your last question, there are many, many examples, 大山 being the most famous one. There should be a large number of others who are simply not as known and/or don’t care about publicity. There is no doubt that it’s possible. If it’s possible for everyone to reach such a level is a harder question and the likely answer is no, but it’s certainly possible to get very far.

I agree with the main point of this article – and I think this actually applies to one’s own native language as well. I personally have spent more *conscious* effort on improving my English pronunciation than my Mandarin pronunciation, and that’s partially because, since my pronuncation of English was already at native level (albeit originally at the lower end of ‘native-level’), improving beyond that is in some ways harder than improving my pronunciation in a foreign language (but the main reason I dedicated more effort is that I was more motivated to improve my English pronunciation).

Another excellent and insightful post, Olle. Very timely for me, as recently I’ve been thinking very much along the lines of your diminishing returns explanation.

I think I disagree slightly though, and would say that there is a point where it really might not be worth getting any better with pronunciation. I would say it occurs at the line between “I am as easy to understand as a native speaker” and “no-one can tell I’m not a native speaker”. I know a lot of non-native English speakers at this level, and sure I can tell they’re not a native speaker within 30 seconds, but it just doesn’t matter.

At this stage, I think it’s nearly always more worthwhile to keeping working on vocabulary building and sentence structuring etc. than to keep tweaking the accent. Unless you’re a spy or something, there’s nothing wrong with having a non-native identity in your speech.

I agree. As I said in the article, the goal wasn’t to tell you whether or not it’s worthwhile, but rather that it’s possible if you really think it is worthwhile. Most people start caring long before “I am as easy to understand as a native speaker”, though. 🙂 I also corrected your comment according to your second comment and then removed that one to keep it tidy.

Olle, you define fossilization as when an adult stops learning. I was under the impression that fossilization is when imperceptible errors of pronunciation enter one’s speech and are practiced so long they are buried under the dirt habit and long-standing practice, and hence become “fossilized”. So the trick is to make the unconscious, conscious. One thing you did not address is the effect a physical limitation, high-tone hearing loss in my case, has on the ability to reproduce sounds in standard Mandarin (especially the s/x/z sounds).

I did mention this in the article, but forgot to include it at the beginning. I have updated the paragraph about what fossilisation is. Regarding physical limitations, that’s something I left out mostly because they are quite individual, but also because I don’t know much about it. I’m curious, though, is it only s/x/z that are affected in your case?

Nice post. I am also very interested in phonetics and how to get a good pronunciation. I am looking forward for any post regarding techniques to improve pronunciation. I’m trying to achieve native pronunciation as I have encountered with at least 4 people that achieved this learning my language. I just couldn’t tell they were foreigners.

Thanks for choosing another good discussion topic.

I agree with you that adult learners can still learn to speak with a native pronounciation/intonation. This is particularly in evidence in actors who have managed to acquire another (believable) accent for a particular role. This shows that with proper instruction and effort this is possible.

Children are under immense peer pressure. They do not like to be different. The very thing that can mark them out as being different is the pronounciation or accent since they otherwise look exactly the same as other children. Hence they will focus a lot of energy on assimilating to their environment. This includes mimicking their peers in order for them not to come across as different. This could explain why they acquire the same pronouncation/accent as their school mates so quickly. However if you ask anyone who has moved to another country below the „golden learning age“ of 12, they will invariable all say it was a very stressful time where they were exhausted and confused at the same time. This then means that learning at this stage is extremely hard and tiring. Do we get this type of exhaustion as adults when learning another language?

As adults, peer pressure for language learning is not so important. You are understood anyway, as you also point out, and people do not tend to point out your poor pronounciation- at least not to your face – as this is considered impolite, as opposed to the children’s playground where morals play a lesser role. Moreover you get praise for trying (whilst failing). So in other words it becomes acceptable on the surface for an adult to have a poor pronounciation in another language.

Incidentally it is the same with grammar. Would you correct a fellow native speaker? For example, I was sat in the garden as opposed to I was sitting in the garden. We would not, because this is considered rude and by the way the grammatical mistake would probably be explained away as it being some dialect thing.

I think though that there are subtle sounds that some adults, but not all, cannot detect anymore which happens if these sounds do not exist in their own language. I wonder if it still then possible for these people to learn these sounds as adults since they cannot hear them. For example, some English peoplecannot distinguish between the u and y sounds.

If fossilisation means that something physically happens that prevents you from learning certain things, I believe it to be more likely that the environment and peer pressure levels change and maybe morals which then makes certain things acceptable whereas previously they were not.

“I think though that there are subtle sounds that some adults, but not all, cannot detect anymore which happens if these sounds do not exist in their own language.”

A long time ago, I saw a documentary which performed some research on this, and the research agrees with you. What the reasearches found was that all infants up to 18 months old with ordinary hearing ability could correctly distinguish all sounds which the human mouth can produce, even sounds which were not used by their caregivers. However, after 18 months, children lose the ability to distinguish sounds which they do not hear regularly (i.e. sounds not used by their caregivers).

Whether adults can later learn to distinguish these sounds with intense focus is a different question.

Well, obviously, the typical case is that we can learn to distinguish new sounds, otherwise it would be utterly hopeless to learn Mandarin for any adult and reaching a respectable listening ability seems to be quite common for people who spend lots of time listening to Chinese. That’s not really an issue, I think, the real issue is production. This is actually what I might write my thesis about, in which case I will also write more about it later here!

Hmmmm … I’m not sure that adults always learn how to distinguish the sounds. My mother claims that she still cannot hear the difference between ‘th’ and ‘s’ in English, in spite of living in the United States and using English has her primary language for over 30 years. However, this does not seem to interfere with her listening comprehension, since context is almost always enough to disambiguate between ‘th’ and ‘s’ in English.

That said, if it were crucial to pick up the difference, I’m sure my mother would have learned how to do it a long time ago;)

I just want to make clear that I didn’t say that all adults always learn to distinguish all sounds, I said that in the typical case, adults can learn to distinguish new sounds in a new language.

Olle, there are actually quite a few sounds that I have trouble distinguishing in English. I’m actually not sure what they are from memory, but the worst sounds are r and s/s-blends. The s/x/z/blends in Chinese are difficult if not impossible because I simply can’t distinguish them if asked just to listen to the sound or word, without a context. The other problem is production because of faulty hearing. I still believe that exposure takes care of the problem of pronunciation, accent, and intonation. The problem is that most people want to talk all the time, and exposure means you are listening.

Yes, the reason I was curious was that I sit here with a list of frequencies of initials in Mandarin and if high frequency causes problems, you should have problems with more than those you mentioned! I was just curious about the general situation, thanks for explaining. I completely agree that people’s urge to speak stops them from being able to speak well. I actually have an article draft written about this very phenomenon. 🙂

I go by the old axiom “what the mind believes the mind can achieve.” It is a matter of setting priorities and being realistic and HONEST WITH YOUSELF. You can speak and sound like a native if you really need to but most people don’t want to take the steps necessary to achieve it. Immersion was the primary motivation for me to speak Mandarin. If I wanted to eat or go to the hospital or get a non Jay Chou I had to speak and be understood. If I hadn’t moved to Beijing seven years ago I would not be speaking Mandarin today. I needed the extra motivation of starving children to push me. Thus I would change your list around to put laziness as the number one or two spot. I don’t agree that older students have more difficulties due to “changes in their brains”… I wish people would cite actual research to back these statements up. Any adult learner who lists lack of time as a reason should keep a log of how much time they spend watching TV, reading Facebook, Twitter etc. By cutting Facebook, Breaking Bad and Game of Thrones out I have added at least an hour a day to my practice. I added another hour by getting up an hour earlier.

That should be non Jay Chou haircut…. I have pictures circa 2006 of my first China haircut… 🙂

I lack interest in finding reasons for “not” doing – well, anything, not just speaking Mandarin without a foreign accent. There is a logical / neuropsychological puzzle in this misguided effort, which is very much like trying prove something does not exist. Rather focus entirely on doing whatever it is you want to do.

One thing missing from my current study of Mandarin is a language lab. 40+ years ago I studied German at a university where they had a language lab, i.e, a room filled with expensive headsets and tape decks where any student could practice hearing and speaking words, phrases and sentences from all levels of proficiency. The machine would play the foreign word, the student would repeat it, the machine would instantly play back the original foreign word and the student’s own version. This worked really well for enhancing the student’s ability to hear and respond accurately, despite the clicking and whirring of electrical relays and tape decks spinning. A good set of earphones muffled all these adventitious sounds.

The closest thing to doing this in real life is to sit down with a fluent speaker and repeat problematic sounds over and over until the instructor validates the results as accurate. Even with this method the student never actually hears himself as others hear him.

With modern computing gear, this type of playback-record-repeat cycle should be easy and cheap to replicate, but I have not found anything like it so far. I believe my pronunciation would improve much more rapidly if I had something like my ancient “language lab” for practie.

Hi! I agree with most of what you write. One of the major advantages with computers is that we all have language labs at home now, even though most people perhaps don’t think of their computers that way. I’m curious what you mean by “I haven not found anything like it so far”? Do you mean that no-one is talking about it or that no-one is doing it? I think it’s fairly common, it’s just that people don’t do it enough. You can also check these articles:

Using Audacity to learn Chinese (speaking and listening)

Recording yourself to improve speaking ability

There’s still no article about mimicking in particular, which is regrettable. I have had a draft for ages, I just haven’t finished it for some reason.