Beginner students often ask if there are any shortcuts for learning Chinese. Learning a language is no simple task, after all, so it’s only natural that we look for ways of achieving more with less energy. So, are there any shortcuts for learning Chinese?

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

Yes, there aren’t any shortcuts for learning Chinese

I have heard or seen this question asked and answered by others many times, often online in various forums and social media. There seem to be two types of answers.

- There are no shortcuts – If you want to learn Chinese, you have to put in the hours and walk the distance; anyone who says anything else is just trying to sell something. Asking this question seems to be a sign of laziness, or that the student isn’t willing to invest enough energy. Get out or buckle down.

- There are plenty of shortcuts – There are many ways to reach your goal, and it follows that not all of these are equally good. There are also many detours you can take or places to get lost, so in that sense, there certainly are shortcuts for learning Chinese.

I think both these approaches have a point, but one of them is more helpful than the other. Below, I will explain why I think it’s a bit silly to claim that there are no shortcuts, and why it is that some people still claim that there aren’t any.

The main road towards Chinese mastery: shortcuts and detours

The reason people answer the question about existence of shortcuts is probably that they mean different things when they say “shortcut” and maybe also that they perceive a lack of willingness to invest time and energy on the part of the student asking the question.

The latter reason is misguided at best, because in my opinion, both smart and lazy people have in common that they want to get as much result out of as little effort as possible. Labelling someone as lazy just because they want to find shortcuts is dishonest and gives the impression that learning Chinese is a about masochism, an endeavour where only effort counts. While effort is clearly needed, there’s more to it than that!

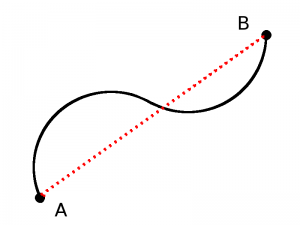

Let’s return to the first reason for the different answers, namely that we mean different things when we say “shortcut”. The analogy being used here is that learning Chinese is like a journey, and a shortcut would then be something that makes the journey shorter, something like the cover image of this article shows. Still, it’s unclear what the main road actually is. Is it what your teacher and course suggest that you do? Or what the average student does? Or something completely different?

What is considered the main road, what is a shortcut, and what is a detour then depends on how you define the terms, which seems unnecessarily nit-picky and not very helpful for learners.

If you want to argue that how and what you study have an impact on your learning, but there still are no shortcuts, you’re free to do so, but then we’re arguing semantics. This might be interesting, but I won’t say more about it here. Instead, let’s have a look at different types of shortcuts.

Walking faster, skipping ahead and avoiding detours

In common language use, a shortcut is something that allows you to achieve a goal faster, either by accelerating the speed or by skipping steps. It ought to be obvious that not all ways of learning Chinese are equally good, so it’s certainly possible to accelerate one’s learning by upgrading the method.

This is what Hacking Chinese is essentially about. In my opinion, it is a bit absurd to claim that all methods are equal, as it would imply that any conceivable method for learning languages would be equally beneficial and this is clearly not the case.

Shortcuts you can use to learn Chinese faster

- Using spaced repetition for learning Chinese characters

- Diversify and spread out your learning in general

- Most things covered on Hacking Chinese

A shortcut can also be something that allows you to skip ahead and bypassing some of the distance to your goal. This is what I think most people who say there are no shortcuts have in mind, because if I tell you that you need to listen a lot to learn spoken Chinese, and that you need to read a lot to improve your writing, there really isn’t any way around that. Yes, you can optimise what you listen to and how you do it, but you can’t skip listening and reading.

There are shortcuts that in practice allows you to skip ahead, though. These are usually insights that save you a lot of time that you would otherwise have wasted. Here are a few examples:

Shortcuts you can use to skip ahead

- Understanding how sound components work in Chinese characters

- Realising that the third tone is actually a low tone

- Getting a good grasp of word formation

Then we have detours, which can either be seen from two angles. If the detour is part of the main road you’re on, then skipping it is certainly a kind of shortcut. If the detour is something only you are doing, it could be argued that skipping it is normal, it’s just that you haven’t realised it yet. Either way, skipping unnecessary detours is important.

Unnecessary detours to avoid when learning Chinese

- Explicitly studying stroke names as a beginner

- Learning complex, explicit grammar on lower levels

- Learning the number of each radical

The last one requires some explanation: Ash Henson of Outlier Linguistics once told me that he first thought the number of each radical was important, and so he memorised all of them. For example, he would learn that 山 is radical number 46. He later realised that this number has no practical function at all.

This is a good example of an unnecessary detour: something you think you should be doing but is actually either optional or a complete waste of time.

What matters is that the time you spend bring you closer to your goal

In the end, it doesn’t really matter if we call things shortcuts, detours or something else, what matters is how much closer you get to your goal for each unit of effort you invest.

It’s not a race to see who can become fluent in Chinese the fastest (if that’s even your goal), but it is about being efficient. I wrote an article about this distinction a while back that discusses this particular point in detail: Learning Chinese efficiently vs. learning quickly

Only some students are interested in learning Chinese quickly, but we are all interested in making sure we get a good return on the time and effort we invest.

Forget about shortcuts; here are the three things that actually matter

Ultimately, there are three factors you can influence that determine how much Chinese you learn. The three factors are:

- Content, or what you learn (what you read, which words you learn)

- Time, or how much you study (counted in hours, not years)

- Method, or how you learn, what activities you engage in

In general, these will show how much Chinese you learn when multiplied together.

Content x Time x Method = Proficiency gain

All of these factors can be manipulated and optimised, and result in what we might call a shortcut.

- If you study the most useful words first, you will reach a communicative goal faster than if you study random words of low frequency.

- If you find a way that enables you to listen twice as much each week, you’ll advance faster than if you don’t.

- If you use spaced repetition when learning characters, you will learn more characters per unite time spent.

I wrote more about the three factors here if you want to know more: Three factors that decide how much Chinese you learn

Conclusion

The bottom line: is this: You are at point A and want to get to point B. There are many ways of getting there, and not all of them are equally long or arduous. When comparing two paths, you can call one of them a detour or the other one a shortcut, it dosen’t really matter, the point is that what you do and how you learn will impact how long it takes you to arrive at point B.

To be honest, I sometimes feel annoyed by people who say that there are no shortcuts. I think I understand why they say so, but I think such answers has a negative effect overall.

I don’t want to make students believe that they can learn without effort, but if you approach learning Chinese with the mindset that there are no shortcuts and that all learning paths are equal, you’re simply going to miss out on a lot of useful things you could do to learn more efficiently.

The principle of understanding language learning, tinkering with it and optimising the process is what language hacking is all about.

It’s not so much about the specific hacks that make learning easier and more fun, it’s about the attitude that learning is not just like walking down a one-dimensional road. It’s up to you to find the best way forward. Don’t let anyone tell you that all ways of learning are equal!