To understand spoken Chinese, we need to convert sounds to meaning. We need to identify sounds of particular interest in Mandarin, combine these and use them to identify words we have learnt, then combine these to form a meaningful whole. Throughout this process, we extract information from what we hear to make sense of it.

To understand spoken Chinese, we need to convert sounds to meaning. We need to identify sounds of particular interest in Mandarin, combine these and use them to identify words we have learnt, then combine these to form a meaningful whole. Throughout this process, we extract information from what we hear to make sense of it.

Like I said in the previous article in this series, this is not all there is to listening comprehension, but it is where we will start. However, keep in mind that we also need to rely on prior knowledge of information that isn’t included in what we hear, and not just knowledge of sounds, tones, vocabulary and grammar, but also about the listening situation, how Mandarin is used in context, and more general things about culture, society and the like. That will be the focus of next article.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

In this article, we’re going to explore the bottom-up processes involved in listening comprehension. A good analogy is that bottom-up processing is like using bricks to build a house. We’re moving from the smallest level of individual sounds to the highest level of comprehension, hence “bottom-up”. The finished house is the speakers intended message, and without building blocks, we won’t be able to construct it.

This article is part of a series about listening comprehension in Mandarin. Here’s a list of the articles I’ve planned for this series so far. Article tittles without links have not been published yet!

- A guide to Chinese listening comprehension

- From sound to meaning in Mandarin

- Using what you already know to aid listening comprehension in Chinese

- Learning to process spoken Mandarin quickly and effortlessly

- Becoming a better listener as a student of Chinese

- Why is listening in Chinese so hard?

- How to master different kinds of listening in Chinese

- Building an arsenal of Chinese listening strategies for every situation

- The best listening exercises to improve your Chinese

Beyond tīng bu dǒng: From sound to meaning in Mandarin

In essence, the goal of bottom-up processing is to convert sound waves in the air to meaning in the brain. This is, when you think about it, quite amazing! While I could make this article ten pages long, I will stick to things I think students and teachers can benefit from and might find interesting. Thus, I will gloss over some parts, such as the anatomy involved in converting fluctuations in air pressure to nerve signals, and the neuroscience of how those signals reach the brain.

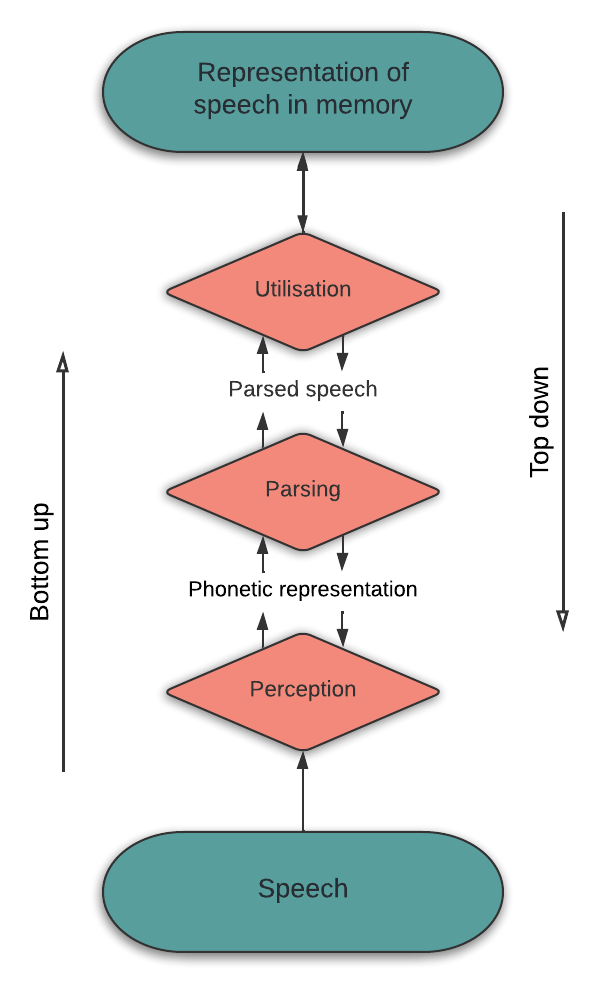

Instead, I will focus on these three steps (from Vandergrift, 2011):

- Perception is about identifying cues in the spoken language which are relevant for Mandarin. For example, we can use tone height and how it changes over time to identify tones, or other acoustic features to identify initials and finals. Other things we recognise from other languages, such as pauses and intonation, although these things differ somewhat between languages too.

- Parsing is about connecting the speech sounds identified in the perception step to the meaning of words stored in long-term memory. The meaning of identified words is activated and stored temporarily in our working memory. The building blocks we need to construct meaning are taking shape.

- Utilisation is where understanding of the spoken language occurs. Words, expressions and structures identified in the parsing step are combined to a meaningful whole, which also involves matching what we hear with what we know, expect and think about the situation, enabling us to interpret and understand what’s being said.

Here’s a visual representation (adapted from Vandergrift, 2012) of these steps and how they relate to each other. You can safely ignore this schematic for now if you prefer as we will return to it at thee end, when I hope it will make more sense.

Step 1: Perception – Identifying speech sounds

Perception begins by paying attention to the spoken language. While we can hear things we don’t actively pay attention to, listening requires attention. This might seem obvious, but exactly what we pay attention to is important, because different parts of the brain are activated depending on what we pay attention to, and in general, we’re better at perceiving things our brains are primed to hear.

The challenge when learning a new language is that there’s so much information contained in spoken language that it’s impossible to process it all. While we don’t need to consciously know what makes a third tone a third tone and what makes a second tone a second tone, our brains need not just the data to build a model to accurately determine which is which, we also need to identify what cues are important.

For example, we all know that Chinese tones are about tone height, so we have high, rising, low and falling tones. However, people’s voices are also different, so children have higher voices than women who have higher voices than men, yet the brain is still able to figure out that a man’s high tone might be lower than a child’s low tone. Added to this, there are other characteristics of tones that aren’t related to pitch at all, which I will cover in more detail in an upcoming article.

There are also many other features that can be difficult to master for language learners. One of the most important ones is aspiration, or the puff of air that follows initials such as p, t, k, c, ch and q in Mandarin. This is the main feature separating these initials from b, d, g, z, zh and j, yet many learners struggle to hear the difference and will often mess up the pronunciation as well.

Figuring out what matters requires exposure over time

There’s also an awful lot of information in spoken language that can and should be ignored. The problem is that something that we’ve learnt to ignore in our native language, might actually be very important in Mandarin. For example, you probably don’t think of the p in “pin” and the p in “spin” as different sounds, but they are, and in many languages, including Mandarin, this difference is important (aspiration, as noted earlier).

Beyond that, each individual speaker has certain characteristics and there are an infinite number of minor variations in pronunciation that aren’t important, yet still present in the input. Teaching the brain to attend to the right cues and ignore the rest takes lots of exposure!

Learning to hear sounds in a new language

There’s plenty of research in the area of sound perception and second language acquisition, but it’s not something that’s fully solved yet (see Escudero, 2009, for an overview). For example, in some cases, learning to hear a new sound can be relatively easy. Consider Pinyin ü, for example, which is tricky for native speakers of English because there is no [y] sound in English.

However, because it doesn’t exist at all in English, it’s usually easy to identify and soon you’ll be able to pronounce it as well. If you think that ü is hard, you can always check out my pronunciation course here. Also, note that Pinyin spelling is different from pronunciation, so not knowing when it’s ü even though the dots are not written out is a different problem (the dots are dropped after j, q and x, and then all the syllables starting with yu-). I wrote more about this here: What’s the difference between Chinese pronunciation and Pinyin? Does it matter?

What’s the difference between Chinese pronunciation and Pinyin? Does it matter?

In other cases, however, new sounds can be terribly difficult to learn, especially if two sounds in the target language are considered one sound in our native language.

The most famous example of this is the inability of speakers of Japanese (and Chinese, to some extent) to perceive the difference between r and l in English. In Japanese, there’s just one sound that varies between r and l depending on context (they are allophones), and suddenly having to separate them and identify them as different sounds is very difficult for adults. Children have no problem with this, but I assume that most people reading this article are adults.

Words aren’t pronounced the same way in all contexts and by all people

Another challenge in the perception step is that the same syllable or word can be pronounced differently depending on the context. For example, to correctly identify nǐ (你), we need to know that when it appears on it’s own, it’s usually a dipping tone, but when it appears in front of most other tones, it’s a low tone, as in nǐ lái (你來) or nǐshuō (你说), and when it appears in front of another third tone, it’s suddenly a rising tone, as in nǐhǎo (你好).

These changes are not limited to tones, of course, but can happen with all types of sounds. A good example is “erization” (儿话音), where an added r at the end of a syllable has different effects on pronunciation depending on what syllable it is. Compare nàr (那儿), where the effect on the preceding vowel is rather slight, with xiǎoháir (小孩儿), where the effect is much bigger.

Then there’s also the problem of stressed and unstressed syllables, where the unstressed ones are typically reduced a lot, especially in Mandarin spoken in northern China. In words like dòufu (豆腐) and yīfu (衣服), the vowel is sometimes dropped entirely, resulting in dòuf and yīf, which don’t even look like Mandarin syllables to the average learner.

To add insult to injury, we also have regionally accented Mandarin, which means that depending on where the speaker grew up, there are additional factors influencing pronunciation. Having spent most of my time abroad in Taiwan, I still sometimes find it difficult to deal with the way people in northern China tend to reduce syllables. People who have learnt Mandarin in Beijing will think that Taiwanese people enunciate words in a way they’re not used to. Many Chinese people pronounce f as h, or n as l, or simply mix them freely, much like Japanese people do with r and l in English. I wrote more about learning regionally accented Mandarin here.

Learning to hear the sounds of Mandarin

The point here is that perception is complicated! For you as a learner, this means that building proficiency takes extensive exposure to spoken Mandarin, preferably from an ever-increasing diversity of speakers. In the beginning, you will find it hard to understand people you haven’t talked to before, or you might even find yourself understanding only what your teacher says, but that’s still a good start! To really form solid mental categories of the sounds of Mandarin, though, you need to diversify your listening, though.

I’ve written more about learning to hear the sounds and tones in Mandarin here.

Potential problems in the perception step

Goh (2000) investigated problems in different stages of listening, and listed the following challenges, most of which we have already covered. The comments in brackets are my own.

- Be unable to recognise even familiar words (because they sound different from what they sounded like when you learnt them)

- Miss what’s said right after something tricky (because your attention was diverted by the tricky passage)

- Be unable to correctly segment the spoken language into words (which is less of a problem in Mandarin, because the limited syllable structure makes it easier to know where one word ends and the next begins)

- Be unable to maintain concentration and be distracted by other things (because listening to a new language is hard work)

Step 2: Parsing – From speech sounds to meaning

In the next step, the main goal is to associate the spoken forms of words to their meaning, which we have (hopefully) stored in long-term memory. If we haven’t learnt the words, or if our recall is too slow, this step will fail and we will need to rely on other methods to figure out what something means (more about this in the next article where we will look at top-down processing).

If you’re a beginner, it’s likely that you will only be able to correctly identify a few words in an utterance. This is not just because you don’t know enough words, but also because parsing takes time. With more exposure to the language and more practise, the process is sped up and you will be able identify larger chunks, not just individual words, which makes the process more efficient. Listening again will also enable you to identify words you didn’t have time to deal with the first time.

Working memory is limited, making listening in a foreign language hard

Our ability to treat larger chunks of the language is also important because of the limited capacity of working memory. It’s hard to specify a number of units that can be stored, bust most will have heard about 7±2, popularised by George Miller in 1956, but the actual number is probably even lower. The point is that if each word is considered a unit, it will be impossible for us to understand longer sentences, because we need to be able to keep what we hear active in order to make sense of it.

This can be easily seen in “repeat after me” exercises that some teachers love. I remember one teacher in Taiwan during my third semester of learning Chinese who said full sentences and then expected us to repeat them verbatim after her, without referring to any notes. This is really hard at a lower level, because students simply don’t have the capacity to keep everything active in their working memory. For the teacher, the exercise seems easy, because for her, the sentence is composed of fewer but bigger chunks that are easier to remember.

A good example of this is structures with 的, which have reverse order in English. For example, we say “that’s the man I saw yesterdays when I went to the store to buy milk”, but in Chinese, “the man” comes at the very end: nà shì wǒ zuótiān qù chāoshì mǎi niúnǎi yùdao de nánrén (那是我昨天去超市买牛奶遇到的男人), or directly translated back to English: [that’s] [I yesterday go store buy milk encounter] de [man].

Beginners find it hard to parse this type of sentence because the sentence doesn’t really make sense until the last three syllables, so you have to keep the rest active until then. With more practice, parsing such sentences becomes easier. Chunking doesn’t expand our working memory, but it allows more efficient use of the limited capacity we have.

Slow recall is sometimes as bad as not knowing the word

Another challenge learners face in the pressing step is processing speed. If it takes us a few seconds to recall the meaning of a word, the speaker will have said a whole sentence in that time, and we’ll have no clue about what they said, even if we did recall that tricky word in the previous sentence.

This issue of listening speed in something I’ve discussed in a separate article, so I won’t dwell on it here, but this is one of the most important reasons why listening a lot is important and that you should practise extensive listening as much as possible. Simply being able to recall what a spoken word means is not enough, you have to be able to do it fast! We will also return to automated processing in an upcoming article in this series.

As your Chinese improves, parsing becomes more dynamic

Finally, we might also struggle with parsing for the more obvious reason that we don’t know the word. Even if we can identify the tone, initial and final to the point where we could write down the word in Pinyin, that doesn’t help much if there’s no meaning stored in memory for that combination of sounds.

For advanced learners, there’s still hope, because we can rely on a deeper layer, namely that of smaller units in the language (morphemes), which are typically single-syllable words (single characters in the written language). If we know that Běijīng Dàxúe (北京大学) means Peking University, we might be able to figure out, on the fly, that Běidà means the same thing, at least with some context. If we later encounter Táià (台大), we already have a pattern and should be able to figure out that it’s short for Táiwān Dàxúe (台湾大学).

If our knowledge of Chinese is rather advanced, we might even be able to guess the meaning of an unknown word by matching the sounds with likely morphemes, but this is quite hard and doesn’t always work. It also requires a deep and internalised understanding of how words are created in Chinese, something I’ve covered in two articles:

The building blocks of Chinese, part 5: Making sense of Chinese words

The building blocks of Chinese, part 5: Making sense of Chinese words

The building blocks of Chinese, part 6: Learning and remembering compound words

The building blocks of Chinese, part 6: Learning and remembering compound words

Goh (1998, 200) identified the following potential problems in the parsing phase, again with my comments in brackets:

- Forgetting what you just heard (either because you were distracted or because you can’t keep all the information active at once)

- Being unable to connect a spoken word with its meaning (because it sounds different than you’re used to, or because it’s buried to deep and takes too much time to recall)

- Failing to understand because of lack of context (which is a top-down process we will look at more in the next article in this series)

Step 3: Utilisation – Putting it all together

Now that we have identified words, expressions and grammatical structures, and retrieved their meaning and are holding them in our working memory, it’s time to put it all together in the last step: utilisation.

Let’s have a look at the graphic representation of Vandergrift’s model again to put everything together:

So far, we have talked mostly about information contained in the spoken language itself (tones, syllables, words and so on), but in order to understand and interpret the meaning of spoken language, we also need to rely on prior knowledge and understanding. When listening, we create a conceptual framework with the goal of making sense of what we’re listening to, relying on what we know about the speaker, the situation and the world around us.

A prototype of the intended meaning emerges

A prototype starts evolving, which is a kind of preliminary idea of what the speaker intends to say. Based on what we understand from subsequent utterances and our prior understanding of the the situation, we can revise and update the prototype. In the utilisation step, we reconcile what we hear with what we already know and expect.

For experienced listeners, this reconciliation is successful, and understanding is achieved. For less experienced listeners, including most second language learners, extra strategies might be needed to understand. This can involve things like relying on context to guess the meaning of words we didn’t understand, realise that something perceived earlier must be wrong in light of things said later, or other forms of problem solving. This problem solving requires attention and cognitive resources that are usually lacking for less experienced listeners, making it very hard to interpret what’s being said or use these compensatory strategies when we fail to understand.

Knowledge about language, culture and society are essential for listening comprehension

It’s possible to succeed with the first two steps (perception and parsing), but fail in the last step, utilisation. A good example of this is when you understand the words someone is saying, but fail to understand why they are saying them. At some point, most learners of Chinese get tripped up by greetings in the form of questions, such as nǐ chī le ma? (你吃了吗), which you can certainly answer if you want, but aren’t really requests for information.

Opening a conversation with similar contextual phrases are common, especially among older Chinese (middle age and up). I remember being puzzled by this the first few times, because I only understood the literal meaning of the question, not It’s a bit like saying “What’s up?” to a learner of English, only to receive a long explanation of what they’re doing, or even worse, “the ceiling” or “the sky”. While a short comment about current activities are okay, the phrase is mostly used as a greeting.

Cultural awareness is important here and makes the utilisation step harder in Chinese than the language of a country culturally closer to your own. People don’t express things the same way and don’t use the same words the same way. A famous example of this is that saying “no” in Chinese often doesn’t mean “no”, but can also be a polite way of saying “yes”. Or in other words, if you hang out with Chinese people and take every “no, thank you” to mean exactly that, you’re likely to miss the intended message quite often.

Beyond tīng bu dǒng: Using what you already know to aid listening comprehension in Chinese

As we have seen, utilisation is not just about the words and patterns we identify, but also about prior knowledge about a whole host of things. This knowledge is needed to understand and interpret not just the literal meaning of words, but the intended message behind them.

This is what top-down processing is all about. Instead of starting from the smallest units and building up, top-down processing is about using what we already know to guide and support perception, parsing and utilisation, and that’s what we’re going to talk about in the next article in this serie: Beyond tīng bu dǒng, part 3: Using what you already know to aid listening comprehension in Chinese

Beyond tīng bu dǒng, part 3: Using what you already know to aid listening comprehension in Chinese

References and further reading

Escudero, P. (2009). The linguistic perception of similar L2 sounds. I: P. Boersma & S. Hamann (red.), Phonology in perception, 15 (s. 151–190). De Gruyter Mouton.

Field, J. (2009). Listening in the Language Classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Goh, C. C. (1998). How ESL learners with different listening abilities use comprehension strategies and tactics. Language Teaching Research, 2(2), s. 124–147.

Goh, C. C. (2000). A cognitive perspective on language learners’ listening comprehension problems. System, 28(1), s. 55–75.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological review, 63(2), 81.

Rost, M. (2011). Teaching and researching: Listening (Second Edition). Routledge.

Vandergrift, L. (2011). Second language listening: Presage, process, product, and pedagogy. In Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 455-471). Routledge.

Vandergrift, L., & Goh, C. (2012). Teaching and learning second language listening: Metacognition in action. Routledge.

2 comments

Thank you so much for all your help, wisdom, and insight. i really appreciate all the effort and learnt ability in a place were lone learners like me can access good instruction.

I think I am cheating because I listen to c-dramas at .75 speed so I can listen to each word. Chinese people talk faster than Spanish Mexican people do so listening whether active or passive is a lot hard, not a bit hard. I am visiting Taiwan in about 2 months is there anything that you can help me with so I might, maybe able, understand what they say at 1000 speed.

Glad to hear you find the articles helpful! I don’t think that listening to slowed down audio is cheating. I am planning to write an article about that specific topic, but in general, slowing down natural audio is a great way of hearing what people are actually saying. Speed is a major problem when processing a foreign language, so giving yourself more time is not a bad thing. Naturally, you shouldn’t only listen to audio at a slower pace, but I think it should be part of a healthy study routine! Listening more than once is also very useful, as it lets your brain process new things it couldn’t possibly handle the previous time (this is true for listening many times as well, not just one extra time, of course).