Digital tools have had an enormous impact on Chinese language learning. If we take something as simple as looking up an unfamiliar character in a dictionary, the process has been changed from minutes of wasted time flipping through a printed dictionary to being able to instantly call up the meaning of a character simply by tapping on it.

Digital tools have had an enormous impact on Chinese language learning. If we take something as simple as looking up an unfamiliar character in a dictionary, the process has been changed from minutes of wasted time flipping through a printed dictionary to being able to instantly call up the meaning of a character simply by tapping on it.

In the past twenty years or so, the number of digital tools and resources for learning Chinese have exploded, and the problem is no longer if there is an app for something, but if you can find the best one among the dozens or hundreds on offer. Making sense of this chaos is not easy, even for someone who spends considerable amounts of time trying to keep up.

I was therefore delighted when I heard that a friend of mine, Julien Leyre, intended to write his dissertation about this very topic. I first met him through the Marco Polo Project and he wrote a guest article about the benefits of translating from Chinese back in 2014. We’ve since collaborated on both Hacking Chinese Resources and Hacking Chinese Challenges, and we have also met on several occasions when he has visited Stockholm.

I was therefore delighted when I heard that a friend of mine, Julien Leyre, intended to write his dissertation about this very topic. I first met him through the Marco Polo Project and he wrote a guest article about the benefits of translating from Chinese back in 2014. We’ve since collaborated on both Hacking Chinese Resources and Hacking Chinese Challenges, and we have also met on several occasions when he has visited Stockholm.

And now he’s finished his PhD! The title of the dissertation is Chinese language learning in the twenty-first century: towards a digital ecosystem? and earlier this year, we sat down to talk about his research, about digital resources for learning Chinese and some related questions. We actually did record video of our talk, but because of technical problems, the image quality is so low that I decided to only publish the audio in this week’s episode of the Hacking Chinese Podcast. I hope you enjoy it!

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the interview:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many other platforms!

If you want to learn more about Julien and his projects, you should check out both his professional website here, as well as his personal one, where he reflects on many things, including but not limited to languages and learning. If you want to know more about his thesis, you will also find contact details on his sites. I have included the abstract at the end of this article.

To help you follow the discussion and make it easier to look up the resources we talk about, here is a brief overview of the topics we talk about. I have not included everything here, but I’ve done my best to link to explicitly mentioned resources:

- Marco Polo Project

- Julien’s article about translation

- Hacking Chinese Challenges

- Skritter (read my review here)

- Hacking Chinese Resources

- Julien’s thesis (contact him for details)

- Pleco

- FluentU (read my review here)

- The Chairman’s Bao

- Speak Chinese in 1000 words (now defunct, redirects to 全球華文網)

- Julien on LinkedIn

- Julien’s professional site

- Julien’s personal site

- The Future of Governance Agency

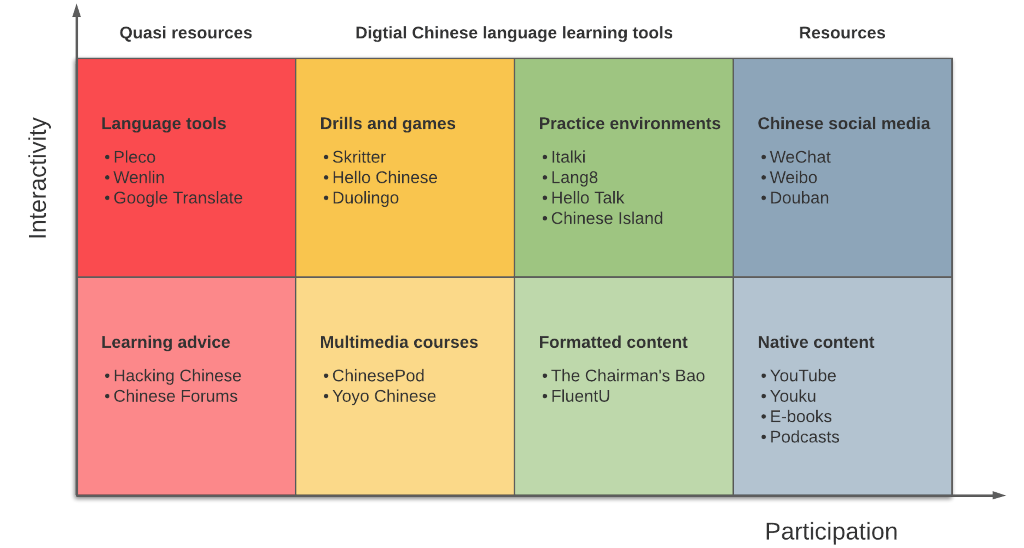

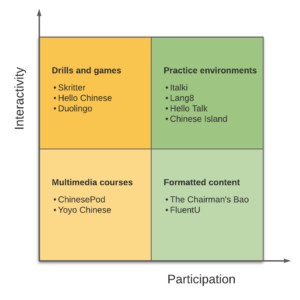

The diagrams used on this page are adapted from figure in Julien’s thesis with only minor adaptions done by me to suit publication here on Hacking Chinese.

Dissertation abstract

Over the last twenty years, a large number of digital tools to support Chinese language learning have appeared. To date, research on these tools has focused mainly on their use in classroom contexts. This growing body of applied linguistics and educational research has yet to be more fully complemented by broader-ranging research in the social sciences on

the formation and development of digital communities of learning. Moreover, there is need to consider these tools against research into the operational structures of digital start-ups and digital ecosystems within business and technology studies. The primary aim of this thesis is to provide just such a multi-faceted account of digital Chinese language learning tools: one that incorporates perspectives and findings from different disciplines and areas of research, to explore how technology has transformed the way we learn Chinese in the early twenty-first century.The theoretical framework adopted in this thesis draws on Pierre Bourdieu’s field theory, Clayton M. Christensen’s theory of disruptive innovation, and Henry Jenkins’ theory of convergence culture. By adopting a transdisciplinary perspective, I seek to gain better theoretical understanding of the commercial, social and political contexts in which the people producing these tools operate, and develop practical understanding to support designers, teachers, and learners in making better tools or using existing tools more fruitfully.

My research was guided by the practical question: ‘How might we map the emerging landscape of digital Chinese language learning in a manner that will yield the most useful common understanding of it for learners, teachers, and designers?’ Two conceptual questions were posed to refine the scope of inquiry: ‘What is the emerging value proposition of digital Chinese language learning tools, individually and as a system?’ and ‘When considering digital Chinese language learning tools, to what extent can we speak of a digital ecosystem being formed?’

This research required a mixed-methods approach. I combined a morphological analysis of 190 tools and their affordances with digital ethnography, drawing on participant observation and interviews to understand the lived experience of designers, learners and teachers. I complemented this approach with systems-mapping and business case studies to track patterns of co-evolution between a set of core tools and the people or organizations that produced them.

I used my analytical findings to generate a typology consisting of four macro-categories of tools: instructional content, drills & games, formatted content and engagement platforms. I present this typology against the changing norms and practice of Chinese language learning in the twenty-first century.

My findings have allowed me to identify distinctive business models used by different types of tool designers, and trace patterns of technological integration and social capital development among people using, making and circulating digital Chinese language learning tools. Although I was able to detect transmedia learning practices, indicating the possibility of Chinese language learning tools evolving into a digital commons, the commercial, social and political contexts in which the people producing these tools operate are such that any emerging ecosystem remains, at best, fragmented.

In sum, this thesis argues that digital tools for Chinese language learning must be considered within multiple contexts if we are to more fully understand their value for institution-based students and online learners. This contextualized understanding opens the practical possibility of improving the way digital Chinese language learning tools are funded, designed and used.

1 comments

So if you were going to start learning Chinese today, how would you do it?