How much time are you investing into learning Chinese? Or is it maybe better to talk about it using a unit other than time, such as how many books you’ve read? Are you reading more than you’re writing? Or is listening, speaking, reading and writing maybe the wrong labels to use?

How much time are you investing into learning Chinese? Or is it maybe better to talk about it using a unit other than time, such as how many books you’ve read? Are you reading more than you’re writing? Or is listening, speaking, reading and writing maybe the wrong labels to use?

People seem to differ in their need to log and record their activities. Some people can’t be bothered, others (including myself occasionally) obsess over it.

Logging your learning has some clear benefits, so if you’ve never tried it, my goal in this article is to convince you that you should. If you already log your learning, I will share some insights regarding how logging is best done and what consequences it can have if done badly.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many other platforms!

In this article, I will introduce logging, what benefits it has, what to log and what that means for your language learning. In upcoming articles, I will look more closely at how to categorise your learning activities and what tools to use for logging. If you know of any great tools for logging progress, please leave a comment below!

What is language logging?

Language logging is the process of recording your progress. It could be anything from putting a checkmark in a calendar for each day you studied at least some Chinese to complicated spreadsheets with detailed statistics of exactly what you did, along with graphs tracking your progress over time. In this article, I’m not too concerned about the exact details, so any kind of logging is included.

Why log your Chinese learning?

Let’s look at a few reasons why logging your language learning can be beneficial:

Logging makes learning visible – As a beginner, it’s easy to feel that you are improving every week, or maybe even every day. That feeling soon goes away, however; welcome to the intermediate plateau! It’s not that you have stopped learning, it’s more that each new thing that you learn has less impact on your overall ability and is thus less noticeable. Learning 50 words when you know 100 is a huge improvement, but has almost no effect when you know 10,000. Logging your learning can help you keep motivated. This is similar to benchmarking, which is about recording the result of your learning, rather than the process.

Logging makes learning visible – As a beginner, it’s easy to feel that you are improving every week, or maybe even every day. That feeling soon goes away, however; welcome to the intermediate plateau! It’s not that you have stopped learning, it’s more that each new thing that you learn has less impact on your overall ability and is thus less noticeable. Learning 50 words when you know 100 is a huge improvement, but has almost no effect when you know 10,000. Logging your learning can help you keep motivated. This is similar to benchmarking, which is about recording the result of your learning, rather than the process. Logging provides an accurate record of your learning – In general, people are bad at remembering duration retrospectively, so the answer to a question like “how many hours did you spend learning Chinese last month?” is bound to be wildly inaccurate, even if you genuinely try to give a good estimate. If you wrote down how much time you spent every day, it would be trivial to add up the hours. Most people tend to overestimate how much they study.

Logging provides an accurate record of your learning – In general, people are bad at remembering duration retrospectively, so the answer to a question like “how many hours did you spend learning Chinese last month?” is bound to be wildly inaccurate, even if you genuinely try to give a good estimate. If you wrote down how much time you spent every day, it would be trivial to add up the hours. Most people tend to overestimate how much they study. Logging makes analysis possible – Without knowing where you are spending your energy, it’s hard for you (or someone else) to figure out why you are not making progress. When I coach people, I usually ask them to log their study activities in detail, at least for a time. I actually ask them to log all their activities occasionally to get a better idea of how they’re spending their time. Naturally, I need this to be able to give advice about learning, but most students say that they learnt a lot about how they spend their time too! It might sound like they should know that already, but most people don’t. This is also part of my course Hacking Chinese: A Practical Guide to Learning Mandarin.

Logging makes analysis possible – Without knowing where you are spending your energy, it’s hard for you (or someone else) to figure out why you are not making progress. When I coach people, I usually ask them to log their study activities in detail, at least for a time. I actually ask them to log all their activities occasionally to get a better idea of how they’re spending their time. Naturally, I need this to be able to give advice about learning, but most students say that they learnt a lot about how they spend their time too! It might sound like they should know that already, but most people don’t. This is also part of my course Hacking Chinese: A Practical Guide to Learning Mandarin. Logging is necessary to balance different areas of learning – Depending on your goals for learning Chinese, some areas are more important than others. If your goal is to be able to interact socially with friends, family or contacts in China, then listening is very important, whereas handwriting Chinese characters is next to useless. Likewise, if your goal is to be able to read texts that relate to your hobby or profession, then spending all your time doing pronunciation drills is not going to do you much good. The point is that without logging your studying, it will be impossible to say if you’re investing your time building the right skills. These examples may seem obvious, but this is not always the case; more about this later.

Logging is necessary to balance different areas of learning – Depending on your goals for learning Chinese, some areas are more important than others. If your goal is to be able to interact socially with friends, family or contacts in China, then listening is very important, whereas handwriting Chinese characters is next to useless. Likewise, if your goal is to be able to read texts that relate to your hobby or profession, then spending all your time doing pronunciation drills is not going to do you much good. The point is that without logging your studying, it will be impossible to say if you’re investing your time building the right skills. These examples may seem obvious, but this is not always the case; more about this later. Logging allows you to set better goals – When setting goals for your learning, the best approach is to aim high, but not so high that the task seems insurmountable. If the goal is not ambitious enough, most people will simply do less. If the goal is too ambitious, you can’t really own it and feel that it’s something that you can do, which might make you give up entirely. For more about goals and motivation, check out Scott Young’s guide to motivation here. Unless you log your studying, you can’t really set reasonable goals. For example, let’s say you want to use the current listening challenge to boost your listening ability for an upcoming exam. How much is “ambitious, but not unreasonable”? Without knowing how much you normally listen, that question is impossible to answer.

Logging allows you to set better goals – When setting goals for your learning, the best approach is to aim high, but not so high that the task seems insurmountable. If the goal is not ambitious enough, most people will simply do less. If the goal is too ambitious, you can’t really own it and feel that it’s something that you can do, which might make you give up entirely. For more about goals and motivation, check out Scott Young’s guide to motivation here. Unless you log your studying, you can’t really set reasonable goals. For example, let’s say you want to use the current listening challenge to boost your listening ability for an upcoming exam. How much is “ambitious, but not unreasonable”? Without knowing how much you normally listen, that question is impossible to answer. Logging allows you to share your learning – You shouldn’t walk the road to Chinese fluency on your own. One way to invite other people to help you out is to share your progress. This allows them to offer help, encouragement or accountability, depending on who they are and what you need. Personally, I found the accountability of Hacking Chinese Challenges very useful! If my progress wasn’t publicly available, I would definitely study less.

Logging allows you to share your learning – You shouldn’t walk the road to Chinese fluency on your own. One way to invite other people to help you out is to share your progress. This allows them to offer help, encouragement or accountability, depending on who they are and what you need. Personally, I found the accountability of Hacking Chinese Challenges very useful! If my progress wasn’t publicly available, I would definitely study less.

Measuring language learning: Dimensions and units

The dimensions and units we use to measure learning matter. The first problem is what dimension to use. If you want to read more, do you count how much text you have covered, or do you count how much time you’ve spent?

Both can be misleading!

If you count time spent reading, it can be tempting to unduly round up the time you spend (let’s count 51 minutes as an hour) or simply count time when you aren’t reading (keep the timer on while taking a break).

It seems clear then that counting how much text you read is better. If you read for 51 minutes, then you will have read less than if you read for the full hour. If you take a break in the middle, the character count is not going up by itself.

But then you realise that this is also problematic, because the true goal of reading is understanding the text, which is not even measured! That means that if you really just want to reach your goal, you could read faster but with less comprehension. Or just stay away from the texts you really should read because they take too long. In certain cases, reading easier things might be desirable (extensive reading is great, after all), but this is not always the case.

Hacking Chinese Challenges: Tracking time spent vs. amount of Chinese covered

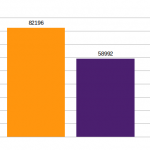

When designing Hacking Chinese Challenges, where I run monthly free challenges with the aim to encourage everybody to study more through daily practice and friendly competition, which dimensions to use was discussed a lot. The system can actually accommodate both units of Chinese covered and units of time spent, but all challenges nowadays are using time only.

Why?

The reason is related to units. It’s often hard to come up with concrete units of Chinese that match what you’re trying to do. How do you quantify pronunciation practice? What about learning words? You might think the latter would be easy, just count the number of words!

But what do you mean by learning a word? Do you also need to know the constituent characters? What about usage? Related grammar? Collocations? Down the rabbit hole we go…

Tracking the time you invest is practical and useful

No, forget about tracking the language itself; it’s better to stick with time as a unit, which is at least easy to measure. This matters. For example, while it would be possible to count how many characters you read for a reading challenge, do you really want to do that? What if you read a printed book? Now you suddenly need to start guesstimating how many characters each page contains. That certainly does not count as reading practice, so is of little value for language learning.

This quote from William Bruce Cameron (often misattributed to Albert Einstein) captures the idea neatly:

“Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.”

In other words, there are many things we engage in when learning Chinese that cannot easily be counted, and some of the things that can be counted don’t really matter. We shouldn’t confuse our measurement of learning with learning itself! I wrote much more about this here: The importance of counting what counts when learning Chinese:

The importance of counting what counts when learning Chinese

Does spending more time necessarily lead to more learning?

Logging the time we spend studying means that we are assuming that our study method is valid. In other words, we think or hope that our practice transfers to the real-life situations we envision ourselves to use Chinese in. We assume that our study method is valid.

In general, the further away your practice activity is from the real thing, the more careful you need to be. If your goal is to get better at reading Chinese newspapers, the most obvious way to practice this is to do just that: read Chinese newspapers.

There are many other activities that could be helpful, such as studying supplementary grammar and vocabulary, looking at the structure of a typical news article and so on, but if you stray too far from the main activity, you risk engaging in activities that don’t really transfer well to the target activity. This can be very tricky to evaluate, as language learners are typically not experts in second language acquisition, and even people who are, disagree on certain things. For example, it seems clear that listening has a considerable impact on speaking, but speaking itself has nowhere near the same effect on listening:

Is speaking more important than listening when learning Chinese?

Investing more time is good, but in what area?

In some cases, the problem you’re facing is not even in the area as it appears to be in. For example, if your pronunciation is bad, it could be that your listening is to blame, but if you find it very hard to understand spoken Chinese, maybe it’s actually your weak vocabulary that trips you up, not your ability to perceive and parse spoken Mandarin. I’ve written more about this here: Are you practising Chinese the right way? Is your method valid? For listening problems in particular, check Chinese listening strategies: Problem analysis.

Are you practising Chinese the right way? Is your method valid?

Using time as the dimension for logging also assumes that you are honest in terms of counting time, but since honesty towards yourself is necessary for any logging to make sense, this is not really an issue.

Time is also practical because most people plan their lives that way anyway. For example, you can schedule half an hour of reading every morning and be sure to get to work on time, but you can’t guarantee that you’ll be able to finish one chapter in a book in that time.

Logging things other than what you study and how much

In the next article in this series, we’re going to look at how to break down and categorise your learning, but it’s worth mentioning here that you can and should log things beyond what you did and for how long. Here are some things worth recording:

- Goals or milestones reached – If you have set up concrete goals and maybe milestones along the way, noting when you reach these can be very motivational. This also allows you to look back and see that you have come a long way.

- Actual language content with personal notes – I’ve already talked about benchmarking above, but you don’t have to make that a separate activity. If your language log is digital, you can include multimedia or otherwise link to specific language content (a recording, an article, a test) along with your notes, thus allowing you to compare at a later date. “Apparently, three months ago, I thought this article was incomprehensible, but I can make sense of it now!” or “Last week mi Chinese sounded like this, how could my tones have been that bad back then?”

- Questions or problems you have – Keeping a list of things you’re not clear about or areas you need to improve can be very helpful. I’ve written more about this in Why you really should use a Chinese notebook. Apart from knowing what you need to work on and what to ask your teacher next time, it can also be highly motivational to later look back and wonder how something you now think is obvious could confuse the less experienced version of yourself so much.

- Noticeable effects on your language ability – It’s tricky to keep variables separate outside of a language laboratory, so while you can’t be sure that doing more of A actually is because you’ve done more of activity B recently, noticeable effects on your Chinese are worth noting. If you suddenly can hear the difference between tone pairs you’ve been struggling with, or feel that you can better guess the pronunciation of characters after learning about phonetic components, write it down!

- Study hacks and learning strategies – Learning a language is one of the best ways of learning how to learn. I can provide you with a plethora of hacks and strategies, but it’s ultimately up to you to try them out and see what works for you. For example, figuring out what works for you in terms of mnemonics (memory techniques) is about trial and error. Write down what works and what doesn’t!

Rounding off, moving on

Naturally, if you write down everything I’ve suggested above about every learning activity you engage in, you will spend as much time logging your learning as you spend learning. Even if you do your logging in Chinese (which I recommend once you reach an intermediate level), this is probably not a good idea! You don’t have to do everything I say above; these are merely suggestions of what you might want to consider noting down.

Personally, I have varied my logging a lot over the years. I’ve usually kept a notebook for questions and problems I want to tackle at a later time, and I have used various systems for tracking how much time I spend on various learning activities. Nowadays, I don’t log my learning at all, beyond using Hacking Chinese Challenges every month. And that’s okay! How much you want to log is up to you.

In the next article in this series, we’re going to look at how to categorise learning activities, with the goal of creating and maintaining a healthy diet of Chinese practice, tailored to who we are and why we’re learning Chinese.

Continue reading: Chinese language logging, part 2: A healthy, balanced diet of Mandarin.

Chinese language logging, part 2: A healthy, balanced diet of Mandarin