Most Chinese characters are compounds, meaning that they consist of several meaningful components rather than being pictures that can’t be broken down. In this series of articles, we’re learning about Chinese characters, the components they consist of and how they fit together.

Most Chinese characters are compounds, meaning that they consist of several meaningful components rather than being pictures that can’t be broken down. In this series of articles, we’re learning about Chinese characters, the components they consist of and how they fit together.

As we saw in the previous article, learning the building blocks is extremely important, because it changes the task of learning thousands of characters from learning unique symbols to learning to combine symbols you already know, which is much easier.

In this article, we will look at the most basic level of the Chinese writing system, meaning the smallest, meaningful units. These characters that are not themselves composed of smaller, meaningful parts and can’t be broken down. We can call these the basic building blocks of Chinese. Technically, these can be broken down into individual strokes, but this is rarely helpful, in the same way that you don’t gain any better understanding of the number 8 by breaking it down into two zeroes.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many other platforms!

This article is part of a series called The building blocks of Chinese, explaining the Chinese writing system. Here are all the articles in the series:

- Part 1: Chinese characters in a nutshell

- Part 2: Basic characters and character components

- Part 3: Compound characters

- Part 4: Learning and remembering compound characters

- Part 5: Making sense of Chinese words

- Part 6: Learning and remembering compound words

Learning basic characters and components

Written language started out with pictures. Perhaps an inscription was used to show that wheat was stored in a certain vessel, then someone had the idea to use that symbol to represent wheat in general, maybe for accounting reasons. Along with basic numbers, writing made it possible to show how much wheat a granary held or how many sheep a villager had paid in taxes.

Written language started out with pictures. Perhaps an inscription was used to show that wheat was stored in a certain vessel, then someone had the idea to use that symbol to represent wheat in general, maybe for accounting reasons. Along with basic numbers, writing made it possible to show how much wheat a granary held or how many sheep a villager had paid in taxes.

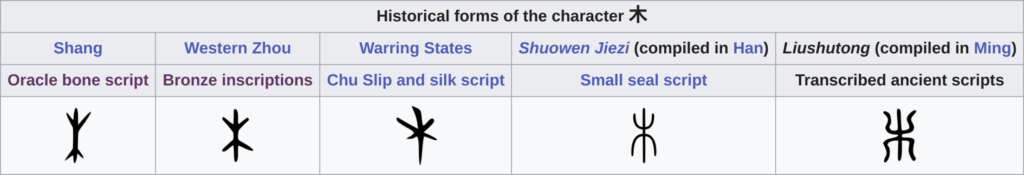

The script developed and was also used for other purposes, such as divination. In fact, the earliest known Chinese characters were carved into animal bones and tortoise shells more than three thousand years ago. This is called oracle bone script (甲骨文). Naturally, the characters have changed a lot over the millennia, so don’t expect them to look like what they originally depicted today. In the table below (from the Wiktionary entry for 木), you

can see how the character for “tree” evolved:

Radicals and character components

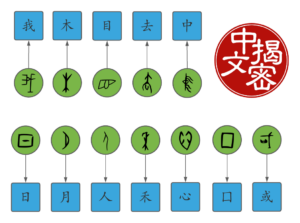

There are a couple of hundred commonly used pictographs and most of these also appear as components in other characters. We have looked at three so far in this series (see the previous article):

- 木, tree

- 人, person

- 日, sun

- 月, moon

- 中, middle (originally showing a war banner around which soldiers rally in battle)

The best place to start if you want to learn more about the most common components is to have a look at the most common radicals. A radical is not really a type of character, it’s rather a function that a component has inside of a specific compound. The function of a radical is to sort the character so it can be found in a dictionary.

In a traditional dictionary, all characters that have 人 as the radical would then be put into the same section, and all the ones with 木 would be put in another. It follows that each character only has one radical, so in 明, “bright”, the radical is 日, “sun”. 月, “moon” is not the radical, but it can be the radical in other characters. It’s often impossible to know which the radical is in a character, although it’s often the component on the left in compounds like 明. Which component is the radical can also be different in different dictionaries, standards and eras. Learning which component is the radical is largely irrelevant for students today, so you can safely ignore that.

In order to help you learn the most common radicals, I have created a list with 100 essential ones all students should learn: Kickstart your Chinese character learning with the 100 most common radicals.

Kickstart your Chinese character learning with the 100 most common radicals

It’s important to understand that not all components used as radicals are common, so stopping at 100 is reasonable. Also note that they are important to learn not because they are radicals, but because they are also commonly used in compounds, usually to to represent meaning, but more about that in the next article.

There are also many components that are never used as radicals, but are still very common, so while the list above is a good place to start, it’s not enough. 中 , “middle”, is a good example, because while it’s often used as a component in compound characters, it’s not used as a radical. A useful approach to learning common components is to pay attention and look up anything that seems to appear often (more than once in different characters you’ve encountered). I’ll introduce the most important tools to do this later in this article!

How to remember basic characters and character components

To learn basic characters (those that started out as pictures and aren’t compounds; we’ll deal with the rest in later articles), the first step should be to look up what the original character depicted. In some cases, this still makes sense even thousands of years after the characters were first created.

Have a look at these, for example:

- 火, fire (you can see a flame with sparks flying off)

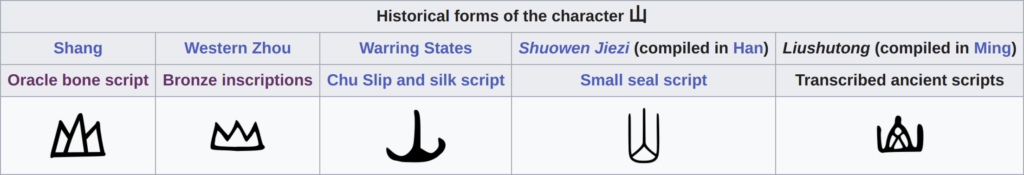

- 山, mountain (a mountain range with three peaks)

- 田, field (divisions separating land into plots)

Here are some earlier forms of the character for “mountain” (source: 山 on Wiktionary):

Of course, you would probably not have guessed that 火, 山 and 田 meant “fire”, “mountain” and “field” respectively if I hadn’t told you, but I’m sure that you can see the resemblance now and that will make it easier to remember the characters!

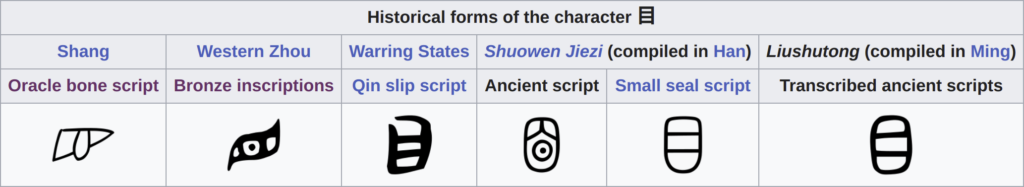

This method can be useful in less obvious cases. For example, you might not think that “eye” 目 looks anything like an eye, but what if you lay it on its side and make the middle compartment smaller, forming the iris of the eye and the outer, bigger compartments forming the whites?

Source: 目 on Wiktionary.

Source: 目 on Wiktionary.

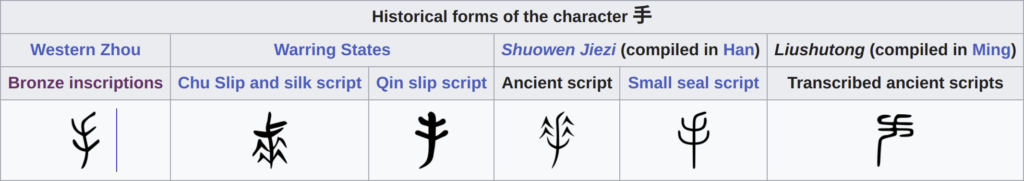

Or take “hand” 手, which doesn’t look much like a hand now, but used to actually have a wrist (at the bottom) and five appendages, even if it looks more like six today. Imagining a six-fingered hand still makes this character easier to remember!

Source: 手 on Wiktionary.

Source: 手 on Wiktionary.

We will look more at how to train your memory to remember things more effectively later in this series, but if you want a hint right now, try to create images or associative stories that are as vivid as possible. Our brains are very good at remembering things that stand out! You can read more about this here as well: Remembering is a skill you can learn

What if the original picture isn’t helpful?

If the actual evolution of a character doesn’t make sense or you feel that it doesn’t really help you, feel free to ignore it! It’s perfectly okay to make things up, as long as you don’t mix components together.

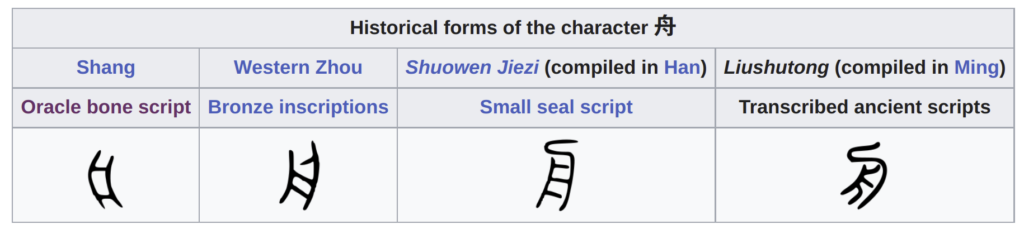

For example, the character 舟 originally depicts a boat, which is also the modern meaning. If you don’t find that helpful (judge for yourself by checking the evolution of this character below), but you do find it easy to remember it by picturing a submarine with the tower sticking up over the water, maybe with people inside and a periscope sticking out, that’s fine. That’s obviously not what the character originally showed, but if it makes it easier to remember, then by all means go for it.

Source: 舟 on Wiktionary.

Source: 舟 on Wiktionary.

Still, try to avoid mixing components together. In the previous article, we learnt that 休 (xiū), “to rest”, shows a person 人 (rén) next to a tree 木 (mù), but if you want to make up your own image or story, make sure that you use 人 (rén), “person”, and 木 (mù), “tree”, as separate components. It’s a really bad idea to come up with something on your own that violates this, because remember what I said in the previous article: learning thousands of unique symbols is very hard, but learning to combine a few hundred you already know is easier. Both 人 (rén), “person”, and 木 (mù), “tree”, are very important building blocks; use them!

How basic is basic? How can you tell?

This article is about basic characters, i.e. those that started out as pictures and can’t be broken down further: the building blocks. This might sound straightforward at first, but it actually isn’t. How do you know that 木 is an unbreakable unit? If you’ve learnt to count in Chinese, maybe you could say that 木 consists of 十 “ten” plus 人 “person”? Or maybe “eight” 八? It certainly looks like that!

But you’d be mistaken. 木 really is the smallest unit here and it shouldn’t be broken down further. We know this because we can trace the character back through history and see that it started out as a picture of a tree, not as a combination of “ten” and “eight” (which doesn’t make much sense anyway).

Keep this in mind when you learn about characters. Many of the tools you can find online are simply looking at the characters from a graphical point of view, so they will happily tell you that 木 consists of 十 and 八. If you think that this helps you remember the character, then fine, but do not trust these tools if your goal is to understand the characters! Instead, use the ones I suggest later in this article.

Characters that look like compounds but actually aren’t

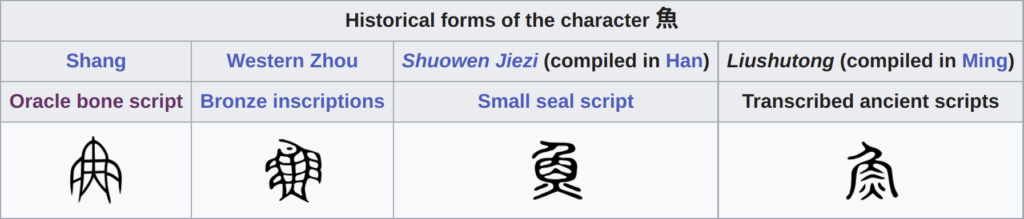

In some cases, it can be even less obvious that a character is the smallest meaningful unit. Take the character for “fish” 鱼. Doesn’t that look like it contains the character for “field” we saw earlier, which would make it a compound and not a basic character after all?

Source: 魚 on Wiktionary.

Source: 魚 on Wiktionary.

But it is just a picture of a fish. The middle part just ended up being written like “field” in the modern form. The point is that there’s no way you could have known that just by looking at the character, you really do need proper tools to learn about this!

How much you care about what the character actually meant originally and what is etymologically accurate is up to you, of course, and we will return to this debate in the next article. It’s not inherently wrong to assign meaning to strokes and parts of characters as long as you know what you’re doing. It’s fine to remember the dot at the top of 舟 as a submarine periscope (see above), but it would be absurd to associate all dots with periscopes. Similarly, if you think it’s easier to remember how to write “fish” by associating the middle part with “field”, then by all means do so.

Tools for learning about basic characters and character components

Let’s look at a few tools for learning about basic characters. For example, how can you look up 中, “middle”, and learn that it originally depicted a war banner and then came to mean “middle; centre”? Or how do you know what the original “eye” 目 looked like? Or that 鱼, “fish”, is unrelated to 田, “field”?

- Pleco is the best dictionary app for learning Chinese, available both on iOS and Android. While you can purchase extra dictionaries and add-ons, what comes with the free version is already quite useful. However, be aware that it does make use of a simple graphical breakdown of characters, so it will show 木 consisting of 十 and 八, and that 田 really is a part of 鱼.

- The Outlier Linguistics Dictionary of Chinese Characters

is probably the best investment you can make as a student of written Chinese. The essentials edition, which is enough for most students, costs less than $23 (single purchase, lifetime access, using the discount code “hacking25”). I have written a full review of the dictionary here and I consider it the most useful tool for learning about characters. Outlier’s dictionary is far superior to other free alternatives in that it is academically sound and well-researched. It does not claim that 木 consists of 十 and 八, nor that 田 is a part in 鱼. They also offer a character course, also covered by the discount code above. I don’t really recommend it to pure beginners, though, as you’ll get more out of it if you already know some characters.

is probably the best investment you can make as a student of written Chinese. The essentials edition, which is enough for most students, costs less than $23 (single purchase, lifetime access, using the discount code “hacking25”). I have written a full review of the dictionary here and I consider it the most useful tool for learning about characters. Outlier’s dictionary is far superior to other free alternatives in that it is academically sound and well-researched. It does not claim that 木 consists of 十 and 八, nor that 田 is a part in 鱼. They also offer a character course, also covered by the discount code above. I don’t really recommend it to pure beginners, though, as you’ll get more out of it if you already know some characters. - Wiktionary is a decent free alternative if you want to learn more about characters. Simply search for the character you’re curious about, such as 中. You will then find information about the character, including how it evolved and changed over the centuries. The illustrations of early character forms used in this article are from Wiktionary.

- Skritter

is an app for learning characters and words using spaced repetition and highly responsive on-screen writing with your finger or a stylus. See my in-depth review here. The reason I recommend it here is that I have designed a character course for Skritter that takes you through the same content as this article series and then some, but in more detail and in a well-produced video format! You get full access to the course even during the free trial, and if you want to stay after that, you get 10% off by using the code “HCSKRITTER” or by following this link and signing up on the website. Monthly subscriptions are $13.5 with the discount code, but goes as low as $7.5 if you subscribe for a year using the code.

is an app for learning characters and words using spaced repetition and highly responsive on-screen writing with your finger or a stylus. See my in-depth review here. The reason I recommend it here is that I have designed a character course for Skritter that takes you through the same content as this article series and then some, but in more detail and in a well-produced video format! You get full access to the course even during the free trial, and if you want to stay after that, you get 10% off by using the code “HCSKRITTER” or by following this link and signing up on the website. Monthly subscriptions are $13.5 with the discount code, but goes as low as $7.5 if you subscribe for a year using the code.

Here’s a trailer for Skritter’s character course where Gwilym James presents the content:

A note on simplified and traditional Chinese

As most of you probably know, there are two sets of characters in use today: simplified and traditional Chinese. The former is, as the name implies, part of an effort to make Chinese characters easier by standardising simpler forms of characters, and started in the 1950 in China. Note that “easier” here usually means “fewer strokes”, and it’s debatable whether this actually makes them easier to learn, especially today when most people don’t write by hand anyway. For an in-depth discussion of this question, check out: Are simplified characters really simpler to learn?

Traditional characters, on the other hand, retain many older and more complex forms and also maintain differences between many variants that have been merged in simplified Chinese. These characters are still in use in Taiwan, Hong Kong and of course in older texts.

I recommend that you learn simplified characters first, unless you have a special connection to one of the areas mentioned above or have a strong preference for some other reason. Once you have learnt one set of characters, switching to the other is actually not very hard. I learnt simplified characters for a year before switching to traditional, and then went back to learn simplified characters later.

In this article series and elsewhere on Hacking Chinese, I normally write simplified characters first and then traditional in brackets or something separated by a forward slash. If I only write one variant, it means it’s the same in both sets or that the difference is not important in that context.

Chinese character variants and fonts for language learners

Finally, a note on fonts and character variation. Most mobile devices and computers will display Chinese characters correctly, but it’s worth noting that the question of fonts can be rather complicated, especially since some characters are written differently in different standards, regardless of if they are simplified or traditional characters.

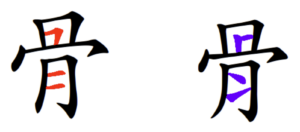

For example, the Chinese word for oracle bone script that we talked about earlier is 甲骨文, That middle character 骨 means “bone” but can be written in different ways, with the small square on the left or on the right. Furthermore, the bottom part can have parallel horizontal strokes or slanting strokes.

Both of these are correct, but they follow different standards. These differences are rather minor and will not cause people to misunderstand something (indeed, most people will not even notice), but it’s good to be aware that this can be a problem! I’ve written more about this issue here: Chinese character variants and fonts for language learners.

In the next article in this series, we will look at how to combine the basic building blocks into compounds. Continue reading here:

https://www.hackingchinese.com/learning-chinese-characters/

30 comments

I use NTNU’s resources to analyse the components and parts in the characters that I select to teach.

They have listed 517 bu4jian4, but the number is for reference only. Ref. http://huayutech.org/mtchanzi/

Here’s a COOL site by NTNU. Ref. http://coolch.sce.ntnu.edu.tw/chinese2/a3.php

try out a flashcard version of Sunrise method and let me know what you think.

https://www.brainscape.com/study?pack_id=1180276

I’m not associated with Memrise in any way, but I would recommend this course/deck that was very helpful for learning all the radicals. http://www.memrise.com/course/47843/common-simplified-chinese-radicals/

This one is even better because it includes both English and Pinyin (with proper text accents) for all the radicals including the various radical forms and audio of the pronunciations. https://app.memrise.com/course/5799949/chinese-radicals/

There’s a recent research article about the way to learn characters. Seems that the researchers are finding about radicals and components just recently as they didn’t refer to Heisig… Anyway, check out their website: http://www.learnm.org/data/

They completed the colossal effort of classifying which component belongs to which character, and all the data is available for download. The only downside is that they only consider components which are characters by themselves or radicals. Still, for anyone interested, their work is a valuable resource.

The two links to your phonetic articles link to part 2!

Thanks for letting me know! I have now updated the first link. 🙂

Why do you recommend learning simplified first?

Good question! I recommend simplified first to the average reader because most people who start learning Chinese will never learn both simplified and traditional (which is the natural destination, in my opinion). Given that they only have so much time to spend on reading and writing, and that most will quit well before they become literate, I think there’s a compelling case to focus on the most useful set first, and that is simplified, mostly because the number of users is an order of magnitude larger. That’s not true if you know you’ll go to Taiwan, for example, which is why I mentioned that in the article.

The conclusion might be different if your goal is to study the writing system itself or if I knew in advance you’d go all the way and learn both traditional and simplified. Then I would recommend learning traditional first, mostly because traditional characters just generally make more sense and there isn’t an extra layer of obfuscation covering some characters (I’m thinking of things like simplifying tons of completely unrelated components to 又, for example). I don’t know your background and how much of this you know already, but if you’re curious, check out this article by Ash Henson from Outlier Linguistics: Are simplified characters really simpler to learn?

Finally, let’s consider learning both at once. Chinese language education in general already has a strong bias towards the written language and it’s not uncommon for students (especially at university) to spend a disproportionate amount of time with characters. While it would be interesting and helpful for acquiring characters if they learnt both sets at once, this would increase the overall time spent with characters, which I think is unacceptable if the goal is communicative ability across the board, not just reading and writing.