Don’t try to learn pronunciation by reading. Instead, the best way to improve is to listen to and mimic native speakers. Focusing too much on how sounds are written down can actually make it harder to hear them!

Don’t try to learn pronunciation by reading. Instead, the best way to improve is to listen to and mimic native speakers. Focusing too much on how sounds are written down can actually make it harder to hear them!

When learning to pronounce Chinese, there are two distinct challenges: learning the sounds and tones of the language, and learning how they are written down. These might seem similar to a casual observer, but they are not, and mixing them up will cause trouble.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode (#218):

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

Don’t learn Mandarin pronunciation by reading

One such consequence is that many beginners think that they can learn one by studying the other, such as learning how words in Chinese are pronounced by looking at the Pinyin.

But this is only true if you have fully mastered both the sounds and tones of the language, as well as how they are spelt in Pinyin. If you haven’t, you can not rely on Pinyin to tell you how something is pronounced.

If I could give one piece of advice to students who want to improve their pronunciation, it would be to stop relying on Pinyin when trying to learn the sounds and tones of Mandarin. It’s fine to use Pinyin to type or to find the reading of a character you don’t know how it’s pronounced, but it’s not a good idea if your goal is to improve your pronunciation. And as a beginner that should be your goal.

Pinyin is not sound; the label is not the thing labelled

The problem is that Pinyin is just a way of labelling sounds in Mandarin using the Latin alphabet, not a way of describing how these sounds are actually pronounced. Naturally, the relationship between letters and sounds is not random, but it’s not the same as in other languages you have learnt and therefore not reliable. In short, you can’t learn pronunciation by studying Pinyin only.

Why learning Chinese pronunciation by using English words is a really bad idea

If I have a box with rice in it and stick a label with the word “rice” on it, that won’t help you if you’re hungry, just like eating a piece of paper with the word “sugar” on it won’t taste sweet, even if the box it was on contains sugar. The word “rice” is not rice, and the word “sugar” is not sugar. Similarly, Pinyin is not the sounds and tones of the language. The former consists of written symbols on paper, the latter consists of sound waves travelling through the air.

Boxes and labels don’t match one-to-one

An additional problem is that sometimes, one label can be used for more than one box, and in some cases, one box can have more than one label. This means that to be able to rely on the labels, you need to know exactly how they are used.

An additional problem is that sometimes, one label can be used for more than one box, and in some cases, one box can have more than one label. This means that to be able to rely on the labels, you need to know exactly how they are used.

Let’s look at a few simple examples of things that can and do go wrong for beginners:

- You learn how to say nǐ (你, “you”) with a dipping tone, then assume it’s the same in nǐhǎo (你好, “hello”) and nǐshuō (你说, “you say”). It’s not. In the first case, it’s a rising tone, and in the second, it’s a low tone. See this article if you need help sorting out how the third tone is actually pronounced.

- You see the -i in shì (e.g. 是, “to be”) and the -i in lì, (e.g. 力, “force”) and assume that they are pronounced the same. They aren’t. Assuming that you’ve heard anyone say shì, you know that neither -i is pronounced with two vowel sounds as in English “shy”, [aɪ]. The vowel sound in English “she”, [ʃi], comes close to the vowel sound in Mandarin lì, [li], but is not at all like in Mandarin shì, [[ʂɻ̩].

- You see the -u in shū (e.g. 书, “book”), and assume it’s pronounced the same as in xū (e.g. 需, “need”), but it’s not. Mandarin shū is not pronounced like “shoe” in English, but at least it’s fairly close. The vowel sound in Mandarin xū is completely different, however, and doesn’t exist in any standard form of English. Many other languages have it, though, such as French (“tu”, meaning “you”), German (“über”, meaning “over”) and Swedish (“ny”, meaning “new”).

When you read Pinyin as a beginner, the natural thing to do is to interpret the sound values of the letters using languages you already know. This is bound to be correct in some cases (m, n, f and l for example, are pronounced pretty much the same in Chinese and English), slightly off in some cases, and completely wrong in others. I’ve sorted out the most confusing cases already in this article (check the podcast episode for audio): A guide to Pinyin traps and pitfalls: Learning Mandarin pronunciation

A guide to Pinyin traps and pitfalls: Learning Mandarin pronunciation

What you see can influence what you hear (and this is bad)

Research also suggests that orthography (the ways sounds are written down; the spelling of the language, if you will) influences how we perceive sounds. If you see the same letter, you are more likely to hear the same sounds. If you see a letter familiar from your native language, you are more likely to perceive the sound as being more similar to the sound of that letter. This is not a good thing if you want to learn to hear the sounds and tones of Mandarin, and still also influence your pronunciation!

Okay, so what’s the alternative then? Listening, of course! Lots of exposure to the language while attentively listening for the sounds and tones, and what makes them different from each other.

Sound references for Mandarin sounds and tones

In this digital era, accessing audio references for Chinese has never been easier. Since Mandarin has such a small sound inventory, it’s trivial to present all possible syllables, even including tones. It’s not trivial to record these (I’ve done so more than once) because there are more than a thousand unique cases, but this is still manageable. Without tones, the number is just a bit above 400.

Here are my top picks for audio references:

- AllSet Learning Pinyin Chart with audio: If you want to check what a certain syllable with a certain tone sounds like, this should be your go-to reference guide. You can also find many other useful things on the Chinese Pronunciation Wiki.

- The Hacking Chinese tone training course: This is a free tool I built with Kevin Bullaughey for a research project. It will present single tones to you in a systematic and carefully planned manner that is meant to help your brain sort out the differences between the tones. It only works for single tones, so this is for those of you who struggle with the basics.

- Free and easy audio flashcards for Chinese dictation practice with Anki: If you want to drill listening, but don’t have access to high-quality premium audio or a real teacher or native speaker, you can create fairly good audio flashcards in Anki completely for free.

- YouGlish: This is a free tool that helps Mandarin learners hear words and phrases spoken in authentic contexts by native speakers, using video clips from YouTube. It’s a quick way to hear how native speakers pronounce words in context. The interface allows you to rapidly hear the same word spoken in many different sentences.

- Text-to-speech (speech synthesis): While synthesised speech is remarkably good these days, it’s not good enough to rely on for pronunciation practice and mimicking. However, it’s good enough for extra listening practice when you really want to listen to a text and don’t have anyone around who is willing to read it for you. Search for plugins for your browser, operating system or stand-alone software for this.

Listen a lot to hear sounds and tones in context

Normally, you shouldn’t be encountering single syllables or even words very often, though, you should be hearing them in context. If the learning material you happen to be using comes with audio, then you have your audio reference right there. Listen before you read!

When working your way through a textbook, put the next chapter on loop and listen to it as much as you can before, during and after you deal with that chapter in class. That way, you will hear the words pronounced over and over.

This is not enough, however, you need more general, less targeted listening practice as well. It goes beyond the scope of this article to recommend listening resources, but fortunately, I have you covered there: The 10 best free Chinese listening resources for beginner, intermediate and advanced learners.

The 10 best free Chinese listening resources for beginner, intermediate and advanced learners

If you’re a beginner, you might also want to check this out: Beginner Chinese listening practice: What to listen to and how.

Beginner Chinese listening practice: What to listen to and how

Confusing spelling rules and difficult sounds

Naturally, not all difficulty comes from reading Pinyin or using your native language to pronounce Mandarin words, some sounds, and especially tones, are just inherently harder to learn. In some cases, the sounds are also tricky to write, leading to the kinds of mix-ups I mentioned earlier.

A good example of this for native speakers of English is u/ü. To explain briefly:

- There are two entirely separate sounds in the spoken language, pronounced [u] and [y]

- The first is a back, close, rounded vowel, similar but not identical to the vowel sound in “shoe” in English (see above). An example would be lù (路, “road”).

- The second is a front, close, rounded vowel, which does not exist in any standard form of English. It’s like the i in the Mandarin syllable lì (力, “force”; see above), but with rounded lips. This results in lǜ (绿, “green”).

- After the initials l- and n-, these sounds are written differently, because both variants exist. Thus we have both lu and lü, and both nu and nü. They are written differently, so any real problem is raised by the pronunciation itself being difficult.

- After any other initial, both sounds are written with only -u (no dots). There is only one possible sound for each combination, though, so if you learn the rule, you know which one it is without looking anything up. After j/q/x/y, it’s always pronounced as ü [y], and after all other initials, it’s u [u]. If you make a mistake here, it can be because you don’t know the spelling rule, you can’t pronounce [y], or maybe both. This is what I meant earlier when I said that you really need to master Pinyin to be able to use it reliably for pronunciation practice.

The upshot of this is that even if you rely mostly on audio references for learning pronunciation, which I strongly recommend that you do, some sounds and tones will still pose a challenge, but a more manageable one.

A rule of thumb you can take with you from this article is this: Never guess how a syllable written in Pinyin is pronounced. If you don’t know for sure, look up an audio reference instead. This avoids cementing bad pronunciation habits.

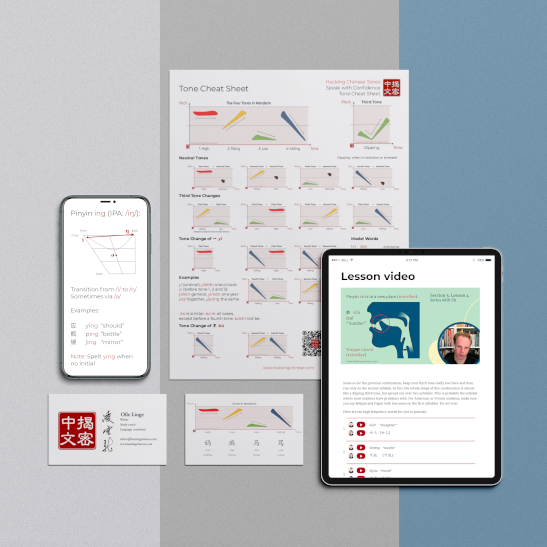

If you want to learn how to pronounce Mandarin sounds and tones clearly and with confidence, check out my pronunciation course:

Pinyin, Zhuyin or IPA?

Assuming that the goal is to learn standard pronunciation, there’s a relatively narrow range of sounds and tones that are considered correct, but there are several ways of writing them down. Including Pinyin (the most commonly used transcription system), Zhuyin/Bopomofo (mostly used in Taiwan) and the International Phonetic Alphabet (mostly used by linguists).

They all describe the same thing (the sounds and tones in the boxes), but in different ways, for different purposes and with different audiences in mind. This also means they are different when it comes to their qualities when used to learn pronunciation. Here’s a quick explanation:

- Pinyin: You can cheat, but it’s very convenient

- Zhuyin: You can’t cheat, but symbols take longer to learn

- IPA: You can sometimes cheat, but at least it’s transparent

If you want to read more about this, I wrote a series of articles about these transcriptions systems, starting here: Learning to pronounce Mandarin with Pinyin, Zhuyin and IPA: Part 1

Learning to pronounce Mandarin with Pinyin, Zhuyin and IPA: Part 1

Conclusion: Don’t learn Mandarin pronunciation by reading

So, don’t learn Mandarin pronunciation by reading. Pinyin is great as a labelling system for sounds you already know, but it’s not meant to describe the sounds themselves. The best way to learn to pronounce Mandarin is by listening and mimicking, not by reading. If you want to learn more about how and why mimicking native speakers is so useful, read this article or check this video on YouTube: