To communicate in Chinese, many different skills need to come together and work in unison. If you’re speaking, word order and word choice need to be on point, but you also need to pronounce Mandarin in way the listener can understand.

To communicate in Chinese, many different skills need to come together and work in unison. If you’re speaking, word order and word choice need to be on point, but you also need to pronounce Mandarin in way the listener can understand.

Each area can be further subdivided, so pronunciation contains initials, finals, tones, prosody, and so on. And these were just a few examples. It would indeed be difficult to even list all the components needed for successful communication.

It’s obvious that when you practise your Chinese, you can’t focus on all these things at once, which leads to an interesting question: Should you focus on one component at a time, or should you try to focus on everything at once?

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

From practising Tai Chi to learning Chinese

I first became aware of this problem when practising Tai Chi, which is incidentally an important reason that I later started learning Chinese. When competing in form (with or without weapons), there are ten criteria on which the judges rate your performance. These include things like “intent and focus”, “martial spirit” and “coordinated movements”, and all these must be present if you want to earn a decent score. Just like my example with pronunciation above, each criterion has many sub-criteria as well.

I first became aware of this problem when practising Tai Chi, which is incidentally an important reason that I later started learning Chinese. When competing in form (with or without weapons), there are ten criteria on which the judges rate your performance. These include things like “intent and focus”, “martial spirit” and “coordinated movements”, and all these must be present if you want to earn a decent score. Just like my example with pronunciation above, each criterion has many sub-criteria as well.

The problem is that nobody can keep ten different things in mind at any given time, so while useful for assessing performance, it’s simply not possible for a practitioner to try to focus on all these areas at once. A better approach is to focus on one area for a while, then shift focus to another. Cycling through the various components in this manner, our overall performance will improve.

This is exactly what it’s like to learn Chinese as well, especially speaking and writing. Our overall ability to express ourselves is based on factors like those mentioned in the introduction, yet it’s impossible to search for the right words while also making sure the third tone comes out right.

Trying to focus on everything at once will only lead to frustration.

Don’t try to improve everything at once when learning Chinese

In general terms, the advice I want to give in this article is to limit your focus when trying to improve. This is especially true when it comes to output (speaking and writing), but it’s also true about input (listening and reading) to a certain extent.

There are two important reasons why focusing on one thing at a time is a good idea:

- Cognitively, we are not able to focus on more than one thing at a time anyway, so trying to do so will lead to a lack of focus on anything. Learning is more effective when focusing on the problem at hand, so sticking to one thing makes progress more likely.

- Emotionally, it’s demotivating to focus on everything at once, at least beyond the beginner stage, because this means that progress is spread so thin that we don’t notice it. When trying to traverse the intermediate plateau, it makes sense to set smaller goals in narrower areas and accomplish those.

So how long should you focus on any given area? And what’s the next step after that?

Start by focusing on the weakest link

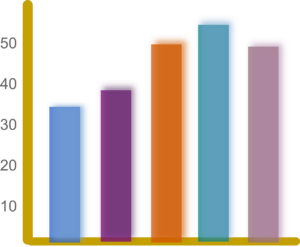

Let’s illustrate the process by imagining several vertical bars representing your level in various areas of Chinese. It’s not important exactly what these represent, and as I’ve already discussed, each area could be further subdivided as many times as you want.

Let’s illustrate the process by imagining several vertical bars representing your level in various areas of Chinese. It’s not important exactly what these represent, and as I’ve already discussed, each area could be further subdivided as many times as you want.

In general, you should focus on the weakest link in the chain first. This is because in the real world, if any one link breaks, communication typically fails. It doesn’t matter than your grammar is perfect if nobody understands your way of pronouncing the words. It’s tempting to focus on what you’re already doing well, but escaping the convenience trap is essential!

When you focus on your weakest link, you should perform noticeably better in that area than when you are focusing on something else. A good example of this is pronunciation: many students can pronounce the tones well, but only if they focus on them. When they focus on something else, the tones are all over the place. Naturally, the opposite is also true, so if you tell someone to mind their grammar and word order, it’s likely that their pronunciation will be slightly worse.

Focus, improve, shift focus, repeat

As you keep focusing on an area, your performance will gradually improve. This could be noticeable in the same practice session, but it could also take longer, especially if you’ve been learning Chinese for a while and this is an entrenched problem. I don’t believe there are problems that can’t be fixed, though, but fossilisation can make the time required daunting.

My suggestion is that you focus on the same area until you’ve made significant progress, then reevaluate your situation. What constitutes “significant progress” is up to you, but from a motivational point of view, you should at least notice the progress before moving on. On the other hand, aiming for perfection is rarely smart either, as the return of investment on the last few percent is incredibly low.

When you shift focus, you might notice that your performance decreases again. This doesn’t feel good, but it is to be expected; if you don’t focus on that area, you should see some regression.

That’s okay. The point is that your base level is now a bit higher than it was before. You have automated a few more components of the larger process, and while your performance is not as good when you focus on something else, it’s still better than it was before.

To return to the bars representing your level in different areas, you choose one of them, raise it a significant amount, and then move on. When you do, it will go back down again, but it will stop at a higher level than before you started focusing on it. As you go through different skills, you’ll automate more of the processes involved, allowing you to perform better even when you’re focusing on something else.

When your teacher doesn’t allow you to focus on one thing at a time

It can be extremely frustrating when working with a teacher or coach who doesn’t understand this. I had once had a diving coach who gave excellent advice, but who shifted focus every single dive. He first told me to wait longer before starting a twist, which I did, but instead of commenting on that, he then told me that my landing was off, so I tried to correct that, only for him to point to some other problem. I ended up picking one or two of the things he said and simply ignored the rest.

This is something I try to be mindful of when teaching and coaching Mandarin pronunciation: if I point out something that isn’t right, I let the student work on that until real progress is made. I don’t then correct other things that might be wrong while the student is focusing on what I’ve already pointed out.

Here’s an example of how not to do it, but that I’ve been subjected to many times:

Teacher: The tone was wrong for this word; it should be a low tone.

[Student tries again, focusing on that tone.]

Teacher: You’re not hitting the [y] sound here; round your lips more.

[Student tries again, focusing on the [y] sound.]

Teacher: The prosody is a bit robotic, try to make it flow more.

[Student tries again, focusing on prosody.]

Teacher: Your third tone in that word is still off.

[Student explodes out of frustration.]

If other people keep shifting the focus for you like this, the best thing you can do is to discuss it with them. Politely tell them that you think that it’s too hard to focus so many things at once, and that you’d prefer to focus on one or two things at a time. Also mention that you’d be happy to focus on any other problems later. Write these things down because you might indeed want to work on them later. If this procedure social awkward or inappropriate, pretending to heed advice while ignoring it can work.

I wrote about this and many other things to do to get the most out of your Chinese teacher here:

How narrowly should you focus?

The ideas discussed above hold true regardless of if we’re talking about something specific, such as “the neutral tone after a third tone”, or if it’s something more general, such as “reading comprehension”. What you focus on depends on too many factors to discuss here, but in general, the more advanced your Chinese becomes, the more important it becomes to focus.

If a beginner or lower-intermediate learner focuses on listening and speaking before reading and writing, that will allow them to make rapid progress in the spoken language, but naturally, they won’t learn many characters. That’s fine; they can shift the focus to the written language later. Still, even if you focus on everything at once, you’ll still make noticeable progress, which feels good and will help you stay motivated.

Should you learn to speak Chinese before you learn Chinese characters?

When you reach the intermediate plateau, however, the feeling of being a little bit better than you were yesterday will disappear. You will find that to make real progress, you need to focus on ever more narrow areas of the language. This doesn’t mean that you must do this, but it does make it easier to stay motivated.

If I as an advanced learner want to improve my speaking ability in Chinese, I need to be extremely specific what I mean. If I just set the goal to improve my speaking ability in general, it would take months or even years to make real progress, and over such a long time, I wouldn’t even notice it anyway. I have spent many thousands of hours speaking Chinese, so investing a hundred hours more would just be a drop in the bucket.

However, if I focused on something more specific, such as lecturing about second language acquisition, or talking about computer science in Chinese, I would certainly make noticeable progress in a hundred hours. This would make the whole project feel more worthwhile and would also have more impact.

Focus your learning with Hacking Chinese Challenges

One way to focus your learning is to participate in Hacking Chinese Challenges! These are free monthly challenges meant to build language skills through daily practice and friendly competition. Each month, there’s a new challenge with a new focus, usually of the broader kind (reading, listening, etc.), but sometimes also more specific (mimicking, handwriting). You can learn more about Hacking Chinese Challenges here or by listening to this podcast episode:

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to learn more about Hacking Chinese Challenges:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

Conclusion: Limit your focus, make progress and stay motivated

By limiting your focus, you make sure that you make quicker and more noticeable progress, which is great for motivation. Exactly how narrowly you focus, how many areas you focus on at any given time and for how long is up to you. The bottom line is that if you’re trying to do everything at once, the result will be that you don’t get anything done at all.

13 comments

This post really hits the spot. Keeping focus is truly important.

It is really easy to get overwhelmed or distracted by the tons and tons of things you need to learn or do to get better in Mandarin. I am guilty of that as well. It also applies to the other aspects of life.

I think it would really help to write down your accomplishments for the day / week to get an real score on the results you are getting (if any).

We often equate busyness with accomplishment. We often don’t realize that sometimes the littlest of actions lead to the biggest results (with a lot of free time left over).

Let’s be accountable for our results and use it to direct us in choosing the the things that we should and shouldn’t be doing to progress in learning Chinese.

Thanks for sharing this, Olle!

Great comment, thanks! Writing things down is useful for two reasons: when you think you’re doing nothing, but you’re actually doing quite a lot; and when you think you’re doing a lot, but it turns out that you’re mostly procrastinating. I like keeping track of how much I study and what I do. I especially like checking boxes next to goals. 🙂

Although staying on point with a targeted goal is ideal, I find it a boring and tedious task. “Variety is the spice of life” for me. So, on certain days I just watch SinovisionTV, other days I’ll review my vocabulary flashcards, sometimes I’ll work with a text and once every two weeks I’ll engage in shenghuo kuoyu with a native born speaker.

Granted, I miss/lose lots of content with this schizophrenic learning technique but I’m gradually gaining more confidence in applying what I have learned well.

I did say “at any given time”, though, without specifying how long you should stick to a certain target (other than suggesting that you should feel that you’ve accomplished something before you move on). I agree that variety is essential and I see nothing in this article that is irreconcilable with that. This article is exclusively about when you’re trying to actively improve a skill, so using SRS to learn vocabulary or relatively passive listening aren’t really what I’m talking about here.

Still, variety is essential in this case, too. For instance, you could focus on some tone problem for 20 minutes, then move on to something you know you need to work on with your handwriting. And so on. I think very few people can stick to something like this for longer periods of time and still be productive.