I started studying Chinese in Sweden in 2007 and have been learning ever since: online and offline, at home and abroad, in formal courses and on my own, full time and part time.

I started studying Chinese in Sweden in 2007 and have been learning ever since: online and offline, at home and abroad, in formal courses and on my own, full time and part time.

I’ve told this story in six articles, and it’s now time to cap it off with a seventh and final article. This is not because the story is over and I have stopped learning Chinese, but because the situation has been stable for close to a decade now.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

To make sense of this article and put it into context, you might want to read or listen to the earlier articles in this series first:

- Where it all started

- Learning Mandarin in Sweden

- My first year in Taiwan

- My second year in Taiwan

- Returning to Sweden

- Graduate program in Taiwan

- Teaching, writing, learning (this article)

What I’m doing today and how that helps me learn Chinese

This article covers the years after returning to Sweden from Taiwan in 2014 up to 2023 but is likely to still be relevant for years to come. I will talk about some general things related to advanced learning, but also connect it to my current situation. Frist let’s have a look at what I currently work with. For more information, you can check out my LinkedIn profile here.

I’m a lecturer at the Department of Education, Uppsala University – My job consists mostly of providing professional development for language teachers in the Swedish school system. This takes the shape of credit courses, but also activities tailored to specific organisations or institutions, as well as writing, lecturing and curriculum development. Most of this is about language learning and teaching in general, but some is directed at Chinese language education specifically. I don’t write directly for teachers on Hacking Chinese often, but there are exceptions, such as this bilingual article about using games to teach Chinese: Text adventure games and how to use them in the Chinese language classroom | 文字冒险游戏及其在对外汉语教学中的应用.

I’m a lecturer at the Department of Education, Uppsala University – My job consists mostly of providing professional development for language teachers in the Swedish school system. This takes the shape of credit courses, but also activities tailored to specific organisations or institutions, as well as writing, lecturing and curriculum development. Most of this is about language learning and teaching in general, but some is directed at Chinese language education specifically. I don’t write directly for teachers on Hacking Chinese often, but there are exceptions, such as this bilingual article about using games to teach Chinese: Text adventure games and how to use them in the Chinese language classroom | 文字冒险游戏及其在对外汉语教学中的应用. I’m director of studies for Languages for Specific Purposes, Department of Management and Engineering, Linköping University – We offer language courses both for other programmes and as single-subject courses. As director of studies, I’m responsible for pedagogical matters, and plan and organise our courses. I’ve also been teaching Chinese here for more than a decade, mostly courses for engineers learning Chinese, which explains my interest in the combination of Chinese language and STEM subjects.

I’m director of studies for Languages for Specific Purposes, Department of Management and Engineering, Linköping University – We offer language courses both for other programmes and as single-subject courses. As director of studies, I’m responsible for pedagogical matters, and plan and organise our courses. I’ve also been teaching Chinese here for more than a decade, mostly courses for engineers learning Chinese, which explains my interest in the combination of Chinese language and STEM subjects. I provide a better way of learning Mandarin through Hacking Chinese – It’s a bit silly to introduce Hacking Chinese since this article is published here, but if you’re new and want to know more about the site itself, I suggest you check out the ten-year-anniversary article I published in 2020 and the about page. While I have received invaluable help from others over the years (see the anniversary post for more), there is no team behind the scenes, so I do everything from drafting articles to editing the podcast.

I provide a better way of learning Mandarin through Hacking Chinese – It’s a bit silly to introduce Hacking Chinese since this article is published here, but if you’re new and want to know more about the site itself, I suggest you check out the ten-year-anniversary article I published in 2020 and the about page. While I have received invaluable help from others over the years (see the anniversary post for more), there is no team behind the scenes, so I do everything from drafting articles to editing the podcast. I’m pedagogical lead at Skritter – If you’re not familiar with Skritter, it’s an app for learning vocabulary in Chines eand Japanese. I’ve had many roles in the Skritter team and worked with different things since I started working there in 2014, including blogging, social media, language corrections and content management. The most visible contribution to date is the Skritter Character Course, which was published in 2022. Nowadays, I work mostly with pedagogical matters as we try to make the app an ever better learning tool.

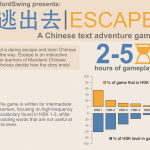

I’m pedagogical lead at Skritter – If you’re not familiar with Skritter, it’s an app for learning vocabulary in Chines eand Japanese. I’ve had many roles in the Skritter team and worked with different things since I started working there in 2014, including blogging, social media, language corrections and content management. The most visible contribution to date is the Skritter Character Course, which was published in 2022. Nowadays, I work mostly with pedagogical matters as we try to make the app an ever better learning tool. I write games for Chinese learners at WordSwing – While I don’t invest as much time as I would like to into WordSwing these days, I’ve contributed to the pedagogical development of the service in general and to the adventure text games for Chinese learners in particular. If you haven’t tried them out, you should! The first game we published is completely free to play!

I write games for Chinese learners at WordSwing – While I don’t invest as much time as I would like to into WordSwing these days, I’ve contributed to the pedagogical development of the service in general and to the adventure text games for Chinese learners in particular. If you haven’t tried them out, you should! The first game we published is completely free to play!

Finding motivation to keep going as an advanced learner

If you thought the intermediate plateau was scary, I can tell you that beyond that lie the endless plains of advanced learning. Here, there’s so much to learn that it’s easy to give up and stick to what you already know. To make noticeably progress, you need to spend enormous amounts of time in a limited area, and even then, it can be hard to notice any difference without proper benchmarking.

I will dedicate an entire article to this subject later, so let’s focus on how I learn Chinese today and what keeps me motivated. As I discussed in the three paths to mastering Mandarin, I believe there are three paths to mastery. Let’s have a look at each and see how I’m doing.

The first path: Using Chinese in your job

If Chinese is an integral part of your job and you encounter different native speakers daily, you will learn a ton of Chinese. Naturally, you will learn more if you focus on studying, too, but the exposure and amount of practice you get will accumulate over the years even if you don’t study. Using Chinese in a professional context will also require you to leave your comfort zone and be able to deal with many different situations.

If Chinese is an integral part of your job and you encounter different native speakers daily, you will learn a ton of Chinese. Naturally, you will learn more if you focus on studying, too, but the exposure and amount of practice you get will accumulate over the years even if you don’t study. Using Chinese in a professional context will also require you to leave your comfort zone and be able to deal with many different situations.

I would estimate that around half my professional life is about Chinese, but most of it is not in Chinese. I’m writing this article in English and most of my professional development courses are in Swedish. I still teach Chinese and one professional development course is for Chinese teachers and in Chinese. I also need to read and listen a lot when doing research for articles, courses and so on.

The second path: Cultivating a genuine interest

Some people spend more time on their hobbies than they do on their jobs. If you can make Chinese the target of such a strong interest, you’re likely to be able to reach mastery. This will power all kinds of useful process, such as turning most of your life into Chinese. Instead of listening to music from your own culture, you listen to Chinese music. Instead of reading books in English, you read everything in Chinese. You might also move to China, but this isn’t strictly speaking necessary. With a moderately strong interest, you can get far, but you need a genuinely strong motivation to reach mastery.

Some people spend more time on their hobbies than they do on their jobs. If you can make Chinese the target of such a strong interest, you’re likely to be able to reach mastery. This will power all kinds of useful process, such as turning most of your life into Chinese. Instead of listening to music from your own culture, you listen to Chinese music. Instead of reading books in English, you read everything in Chinese. You might also move to China, but this isn’t strictly speaking necessary. With a moderately strong interest, you can get far, but you need a genuinely strong motivation to reach mastery.

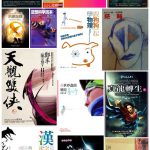

I obviously have a strong interest in Chinese, but my problem is that I’m also interested in many, many other things. Some of these can be combined with Chinese, others not, but the upshot of all this is that I don’t have a strong enough interest to allow me to spend hours on end with Chinese just because I like it. In the article linked to above, I wrote about the 25 books I read in Chinese in 2013, but I’m not focused enough on Chinese to do anything like that now. My interest is enough to keep me going, but it’s not enough to master the language on its own.

The third path: Having your social life in Chinese

If most of your social interactions are in Chinese, you will naturally develop excellent listening and speaking ability, provided that you speak Chinese with them of course. Depending on whom you talk to, what you talk about and how much, this could either be moderately helpful or the key to unlocking mastery. Marrying or otherwise living with a native speaker of Chinese helps, but it’s not a requirement. Preferably, you should interact with a variety of people as well.

If most of your social interactions are in Chinese, you will naturally develop excellent listening and speaking ability, provided that you speak Chinese with them of course. Depending on whom you talk to, what you talk about and how much, this could either be moderately helpful or the key to unlocking mastery. Marrying or otherwise living with a native speaker of Chinese helps, but it’s not a requirement. Preferably, you should interact with a variety of people as well.

My wife and I speak Chinese, English and Swedish, often mixing all three, but in that order of preference. We have been doing that for well over a decade now, though, so this is normally within my comfort zone. Still, there’s an unlimited number of interesting topics to talk about, so I certainly learn new things all the time as well!

Teaching is an excellent way of learning Chinese

If you have the chance, teach Chinese. It’s an excellent way of reinforcing what you already know and identifying things you only think you know. It needn’t be a formal course, or even a course at all, you could teach a beginner privately or volunteer somewhere that teaches Chinese. I’ve written an article about why teaching is so good for learning: Use the benefits of teaching to boost your own Chinese learning

Use the benefits of teaching to boost your own Chinese learning

Learning Chinese: A fifteen-year lesson in humility?

I’ve been learning Chinese for well-over fifteen years at this point, but there are so many things I don’t know and so much left to learn. This sometimes weighs on me, even if I know there’s no reason to let it. I can use Chinese freely in the contexts I care about and that’s what matters.

To make quicker progress, I would need to invest more time and energy into my own proficiency, rather than trying to help others improve their Chinese. David Moser put it well in Why Chinese Is So Damn Hard:

Someone once said that learning Chinese is “a five-year lesson in humility”. I used to think this meant that at the end of five years you will have mastered Chinese and learned humility along the way. However, now having studied Chinese for over six years, I have concluded that actually the phrase means that after five years your Chinese will still be abysmal, but at least you will have thoroughly learned humility.

I’ve now learnt Chinese for sixteen years, but while I wouldn’t describe my Chinese as abysmal, I know exactly what he meant. To this day, he’s still very humble about his own abilities, even though he’s now been learning the language for almost 40 years. David also wrote a follow-up article here on Hacking Chinese, discussing how digital tools have revolutionised how Chinese is learnt and taught.

Conclusion of this article and this series

This concludes the story of how I learnt Chinese. As I’ve already said, that doesn’t mean that I’ve stopped learning, and one day I might return to this series as well. In the meantime, I hope you’ve found these articles interesting and inspiring. If you’ve read this far, please leave a comment below and say hi!

Editor’s note: This article, originally published in 2016, was rewritten from scratch and massively updated in July, 2023.

2 comments

Thank you for the series, it was a good read.

I agree that immersing yourself in a Chinese environment will help to improve your Chinese the fastest. I think that goes for any language, and not just Chinese. If you want to improve your French, you probably want to immerse yourself in a French environment. If you’re not in a country where Chinese is the first language, then you want to put yourself in a Chinese environment, if possible. Aside from getting Chinese friends, you probably want to watch Chinese movies, TV shows, and listen to Chinese music for leisure.

Thanks for the good read!