Ideally, all students would acquire perfect pronunciation in Chinese by listening to and mimicking. Sadly, this is only guaranteed to work for children, not for adult learners.

Ideally, all students would acquire perfect pronunciation in Chinese by listening to and mimicking. Sadly, this is only guaranteed to work for children, not for adult learners.

This is easy to show because while children do master the sound system of their first language(s), most adults fail to acquire native-like pronunciation in foreign languages. For most students of Chinese, simply hearing the language and speaking it isn’t enough, even if done for years.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

Still, while age does make it harder to learn pronunciation, it certainly doesn’t make it impossible. You might be too lazy to learn Chinese, but you’re not too old. Most people who fail to achieve clear pronunciation do so because they aren’t willing or able to invest enough time and energy. This is good news, because if you are willing and able to work for it, you certainly can master the sounds and tones of Mandarin.

In this article, we will look at the role of explicit learning and how knowing some theory can improve your pronunciation. This is not the most important ingredient in a successful strategy, though, so let’s quickly discuss where you should invest most of your time before we turn to the role of theory.

Three fundamentals of good pronunciation: listening, mimicking and feedback

The best way to learn to pronounce any language is to combine copious amounts of listening with mimicking and feedback so you can track progress and make sure you focus on the right things. Listening more is straightforward, but if you want some effective ways to increase how much you listen, I have you covered.

Mimicking can be done in many ways, but what I find most useful is to try to repeat something a native speaker says as they are saying it, trying to make what you say match perfectly with what they say. You can do this with a real person or an audio recording. I’ve written more about how to do this using Audacity here: Mimicking native speakers as a way of learning Chinese.

While you can listen and mimic as much as you want on your own for free, getting helpful feedback is trickier. I’ve discussed how to do that here: How to get honest feedback to boost your Chinese speaking and writing. It’s surprisingly hard to do this, which is why I’ve added a feedback option to my pronunciation course, where I will give systematic feedback tailored to beginners or more advanced students: Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence

The course also covers all the theory you need, and since the theory is what this article is meant to focus on, let’s turn to that now.

Why theory can be helpful when learning Mandarin sounds and tones

Beyond listening, mimicking and feedback, adult learners can also benefit from learning some basic theory. I first discovered the importance of theory when learning English at university. I’m Swedish, and when I grew up, we started learning English in school at the age of ten, but all with non-native speakers as teachers. Naturally, ten years of learning inside and outside school taught me a lot about English pronunciation, but it was only when I took a course in phonetics that I noticed some errors I had been making all along.

This website is called Hacking Chinese, not Hacking English, but I’ll include some of the pronunciation errors I spotted at university for the curious. To begin with, I noticed many cases where I pronounced things as they were written, even though native speakers don’t say the words like that. Some examples are “iron”, “salmon” and “column”. I had heard these words thousands of times, yet I had never noticed that they weren’t pronounced as they were written. The importance of vowel reduction was also eye-opening (or ear-opening, perhaps).

Theory is never enough, but it can help you pay attention to the right things

Studying theory isn’t always immediately useful. It’s not like you read something about how a certain sound or tone is pronounced in Mandarin, shout Eureka!”, and you never get it wrong again. This is not how language learning works.

More often, the insight helps you direct your attention so that when you hear native speakers, you notice something that’s different from how you say it. Gradually with practice, this transforms into better pronunciation. Without even noticing that there’s a difference between what you say and what they say, you won’t improve, because, in your mind, you have already reached the goal.

Some examples of how theory has improved my pronunciation in Chinese

Here are some examples of things related to Chinese pronunciation that I have learnt by reading about them, rather than merely listening and mimicking (which I’ve done a ton of too, naturally). I had many opportunities to pick these things up just by listening, but I didn’t; I only figured them out by learning about them.

Depending on your Chinese level, your native language and many other factors, my examples might or might not make sense. They are merely a collection of things that have helped me to show how theory can lead to better pronunciation in general. If you have other examples, please leave a comment!

Here are my examples:

- That the third tone is usually a low tone – This is a problem many foreigners have, and I think the reason is that few teachers accurately explain how the third tone should be pronounced, or if they do, they fail to focus on that beyond the first few weeks. The third tone is just a low tone in front of all tones except another third tone. It has an optional rise when in isolation or at the end of sentences. If you’re aiming for the dipping tone in normal speech, you’re certainly going to get it wrong.

- That “j/q/x” aren’t produced with the tip of the tongue and thus aren’t between “z/c/s” and “zh/ch/sh” – These sounds are instead produced with the tongue tip down. I knew there was something wrong with my pronunciation of these sounds, but it took years until I studied Chinese phonetics and really figured it out. I’ve done several pseudo-scientific experiments with this and even though the sounds produced are similar, there is a distinct difference. I have corrected the pronunciation of enough fellow Mandarin students to know that I’m not alone in having misunderstood these sounds.

- That “z” and “zh” aren’t voiced; only “l”, “m”, “n” and “r” are. It’s common to hear people pronounce “z” and “zh” with voicing, and “s” and “sh” without voicing. This is in line with how “z” and “s” differ in English, where “z” is voiced and “s” is not. But this is not true in Mandarin. None of these sounds is voiced, and instead, the difference is aspiration.

For more examples, check this article: A guide to Pinyin traps and pitfalls: Learning Mandarin pronunciation

A guide to Pinyin traps and pitfalls: Learning Mandarin pronunciation

Now, you might argue that I could have corrected all these problems simply by having a good teacher who could point them out and help me correct them. And you’d be right, except that such teachers are exceedingly rare. I have had well over twenty teachers and only the first error was pointed out to me and that was after having learnt Mandarin for more than two years.

This will be the topic of a separate article someday, but to put it briefly, most teachers lack the time, energy, courage or competence to help students with their pronunciation, so if you care at all about speaking clearly and naturally, you’re mostly on your own.

Resources for learning Mandarin pronunciation theory

If you want to learn more about Mandarin pronunciation, I have created a course that covers everything you need to know. I built this course because I realised that there were no such resources out there. Other courses are either way too theoretical (such as if you study academic courses in phonetics) or not theoretical at all, creating even more confusion by simplifying to the point where what’s taught is wrong.

The course covers how to learn pronunciation, the theory you need to master initials, finals, tones and prosody, along with lots of practical tips and tricks. It also goes through and explains how all sounds are written in IPA (the International Phonetic Alphabet), which will enable you to see how Mandarin is supposed to be pronounced. As mentioned earlier, there’s also a feedback option. Here are some excerpts from the course, starting with the introduction:

Sneak peek: Section 1, Lesson 1: Welcome to the Course

Sneak peek: Section 4, Lesson 2: Finals starting with A

Sneak peek: Section 2, Lesson 4: Tone Pairs

I’ve put all the information about the course, including the full curriculum, answers to practical questions and much more here: Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence

Free resources for learning more about the sounds and tones of Mandarin

I realise that not everybody will be interested in or want to pay for a course, so here are some free resources to help you out. I also include two books which aren’t free unless you can find them at your local library.

- Zein on Mandarin Chinese Phonetics

- Chinese Pronunciation on Sinosplice

- Standard Chinese Phonology on Wikipedia

- The Sounds of Chinese by Lin Yen-Hwei

Conclusion

Listening and mimicking is the foundation of good pronunciation and is enough for children and even for some extremely talented adults, but for most students, it’s far from enough. Add some theory to the mix to help you understand what you’re doing and direct your attention to the right things.

Editor’s note: This article, originally published in 2015, was rewritten from scratch and massively updated in May, 2023.

18 comments

Fascinating!

I’m confused though, I thought the difference between ‘z’ and ‘s’ *was* voicing? At least that’s how it feels to me in English. What’s the distinction in Chinese then?

-Scott

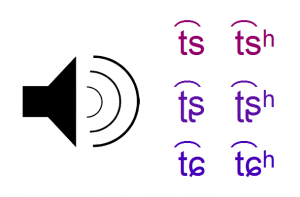

It’s not voicing. “z” in Pinyin is an affricate like Carl N. said, i.e. a combination of a stop and a fricative, in this case a voiceless [t] followed by an [s]. Neither “z”, “zh” nor “j” are voiced, in fact, they are all voiceless affricates. I don’t know how familiar you are with IPA, but the picture in the article lists the pronunciation of “z/c”, “zh/ch” and “j/q”. As you can see, they all start with a voiceless stop, (a voiced stop would be [d]).

Getting quality feedback is not always easy to get. For me, the next best thing is recording my practice words or sentences and comparing with the audio material that I’m trying to learn. This has been a HUGE help with my pronunciation. There are a lot of mistakes I unconsciously make and don’t realize until I playback my own recording and compare. I strongly recommend recording and playing back, its worth the effort.

The pinyin ‘z’ is not equivalent to the English ‘z’ (which is a voiced ‘s’) but instead [t͡s].

“Do not read this book without having read at least one book about phonology and one about Chinese phonetics.”

Any recommendations? (in English or Swedish)

Good question. I have read almost all my Chinese phonetics in Chinese, so I don’t really know, but here are two books you could check Bruce Hayes’ Introductory Phonology and Yen-Hwei Lin’s The Sounds of Chinese. The first is obviously an introduction to phonology in general.

Many thanks for this article, Olle!

I’m interested in pronunciation itself, but I have never heard about the tip of the tongue pointing down with “j/q/x”. I do, however, know that I always had the distinct feeling that my “j”, especially in the syllable “ji”, sounds wrong, without being able to actually pinpoint the problem. The positioning of the tip of the tongue might be the reason why, so any pointers on this would be very much appreciated.

It’s not really the tongue tip that makes the difference, but that’s the easiest way of describing it and probably the easiest way of producing the right sound. The point is that these sounds are not produced with the tip of the tongue, as is e.g. Pinyin t and d. If you glue your tongue tip to the lower teeth ridge, you can’t use the tip to pronounce j/q/x, but will be force to go farther back on the tongue, which is the whole point. Experiment a bit and see if you can get it right!

> Naturally, my English was descent when I started studying English at university ten years later

“descent” (nedtur, nedstigning) –> “decent” (ok, godt nok, mådeligt).

Fixat, tack så mycket! Det rör sig i 99% av fallen om stavfel och det här är nog ett av de vanligare… För skojs skull sökte jag igenom hela sidan. Jag har stavat det rätt i 37/40 artiklar.