Earlier this spring, I asked an expert panel a difficult question: How should we learn Chinese grammar? As I hoped, the answers were as insightful as they were diverse. There are many ways of learning grammar and all have different strengths we can add to our own study method. One of the experts I asked is John Pasden, well-known for his blog Sinosplice, which was one of my main inspirations when I started Hacking Chinese. As someone who has spent a lot of time and energy creating the Chinese Grammar Wiki, it’s only natural that John thought that the few hundred words available for the expert panel article weren’t enough. Therefore, he decided to write a standalone article about how to approach Chinese grammar. And here it is!

What to Expect When Learning Chinese Grammar

It’s best to approach a new, unfamiliar topic without too many preconceptions, but there are two that I hear a lot in regards to Chinese grammar, so I think it’s better to briefly address them both:

It’s best to approach a new, unfamiliar topic without too many preconceptions, but there are two that I hear a lot in regards to Chinese grammar, so I think it’s better to briefly address them both:

- “Chinese doesn’t have grammar.” OK, this is just silly. If there are no rules for how to string Chinese words together, then you could never be wrong, right? Although that sounds nice, it’s just not possible.

- “Chinese word order is just like English word order.” While it’s true that there are some basic similarities, and you can easily find examples like “I love you” that match word for word, it’s not hard to disprove this. Even basic words like 也 (yě) will constantly trip you up if you don’t use them the Chinese way.

You’ve also probably heard that Chinese grammar doesn’t have verb conjugation, or plurals, or cases, and a bunch of other stuff that we language learners generally associate with “not fun.” What does all this add up to? It means that for someone who speaks English, Chinese grammar is not going to stress you out too much. But still keep your eyes out for interesting features and patterns different from English. You will find them.

The Learning Curve

I once compared learning Chinese grammar to learning Japanese grammar. My conclusion is that Chinese grammar starts out pretty easily and ramps up gradually. (Don’t get too smug, though; while you’re not getting flummoxed by Chinese grammar, Chinese tones and characters are ravaging your poor little brain.)

The great thing about this is that it means “get out there and talk” is a great strategy. If you’ve got the vocabulary and a few basic patterns down, grammar is not going to be your biggest obstacle. If you can’t find someone to talk to, then get reading as soon as possible.

I recommend the following learning strategy:

- Learn basic grammar patterns

- Extend your knowledge with experimentation and input

- Go back to grammar resources when you get confused or some grammatical issues just really starts bugging you

Let’s look at each in detail.

Learn Basic Grammar Patterns

You can find these in any grammar book. It’s stuff like:

要 + Verb = “Want to [Verb]”

or

Noun1 + 比 + Noun2 + Adj = “Noun1 is more [Adj] than Noun2”

Sure, if you dig, you can find all kinds of weird exceptions and advanced forms, but to delve into those right away is to waste the advantage provided by the gentle learning curve. Put another way, it’s kind of hard to communicate in a language that requires verbs to be conjugated if you haven’t learned to conjugate verbs at all. But here’s this language that doesn’t require conjugations and has all kinds of simple patterns. Why would you not want to just jump right in? Don’t make it more complicated than it is!

If you’re learning from textbooks or podcasts, they may or may not dwell on the finer points of grammar. As a learner, though, you can choose to take just what you need and get out there and start talking. “Pack light.” You don’t need to finish reading up on all the exceptions of each grammar point in order to have a conversation.

The Chinese Grammar Wiki was designed with this principle in mind. Rather than a “grammar course,” it’s a “resource.” In other words, reference it when you need it. If you don’t need it, great! One of the Chinese Grammar Wiki’s key design elements is to break grammar points down by levels. This can be tricky, because often there are finer points of a particular word’s usage which actually go beyond the basic usage of the word. Often, books will group these all together, a practice which confuses and discourages learners.

The solution we generally favor on the Chinese Grammar Wiki for cases like this is to keep the basic grammar point at the lower level, then create a “sequel” grammar point at a higher level. Obviously, the two will be linked, but the point is to provide a level-appropriate explanation for the lower-level learner so that he can “get in and get out” quickly. (Of course, if that learner wants to go clicking down the grammatical rabbit hole, Wikipedia-style, we won’t stop him.)

The solution we generally favor on the Chinese Grammar Wiki for cases like this is to keep the basic grammar point at the lower level, then create a “sequel” grammar point at a higher level. Obviously, the two will be linked, but the point is to provide a level-appropriate explanation for the lower-level learner so that he can “get in and get out” quickly. (Of course, if that learner wants to go clicking down the grammatical rabbit hole, Wikipedia-style, we won’t stop him.)

One example of this is Wanting to do something with “yao”, which is at the A1 (Beginner) level. Higher-level learners that take a look at this grammar point will be thinking, “hey, wait a minute, there’s a lot more that 要 can mean in Chinese!” Very true. We hold off until level A2 (Elementary) to introduce Auxiliary verb “yao” and its multiple meanings.

The point is to just take what you need and go use it.

Extend Your Knowledge with Experimentation and Input

Once you have your basic grammar patterns and vocabulary down, and you’re out there practicing your Chinese, there are a few other things you can do to get the most out of the experience.

- Focus on meaning when you speak. Use the grammar points that you think will get your point across. If they do, then great. That’s a good sign. If, however, you’re repeatedly using the same grammar point to express a certain idea, and no one seems to understand what the heck you’re talking about, you might want to try another approach, and eventually revisit that stupid grammar point that didn’t work for you.

- Listen for recasting. Very often, native speakers will give you subtle corrections while conversing with you. Many learners are blissfully unaware of these, but if you tune into them, they can be an excellent way to improve your speaking (and it’s a way more enjoyable way of getting corrective feedback than a pile of homework covered in red ink!).

- Go out there and try new patterns. Start conversations specifically to use a new grammar pattern. This kind of experimentation might sound silly and not terribly conducive to real conversation, but the results can be surprising. The way native speakers respond to your shaky, early uses of new grammar patterns will reinforce the meaning and usage of those patterns like nothing else. And you will have awesome conversations.

- When you don’t understand, don’t get hung up on it. A lot of times the grammar, though complex, isn’t actually important to the topic at hand. The 把 (bǎ) construction is a perfect example of this. If you really want to learn it properly, there’s a lot to take in. But you can also completely ignore it for quite a while and do just fine. If you’re having real conversations, ignore the pesky grammar patterns until you can’t!

Following these four pieces of advice will allow you to get more input sooner. This will help accelerate not only your acquisition of grammar, but also vocabulary, listening comprehension, and speaking proficiency. The thing about language acquisition, though, is that it is a largely unconscious process. So you won’t necessarily FEEL the effects of the input, but they will be at work in your brain.

As for the conscious part of the learning process, it’s crucial that you get out there and make contact with the real language. It will breathe life into the grammar explanations that you have already studied if you revisit them later. Furthermore, real communication will fuel your motivation to better express yourself and understand the precise meaning of what other people are saying to you. And let’s face it… that’s what grammar is for.

Go Back to Grammar Resources Later

One of my favorite stories I like to tell is about a client of mine just starting on “Intermediate” material. She was studying ChinesePod lessons, and like many of us, she struggled a bit when she first encountered the 把 (bǎ) construction. The interesting thing, though, was her claim that, “none of the Chinese people I know use this.”

One of my favorite stories I like to tell is about a client of mine just starting on “Intermediate” material. She was studying ChinesePod lessons, and like many of us, she struggled a bit when she first encountered the 把 (bǎ) construction. The interesting thing, though, was her claim that, “none of the Chinese people I know use this.”

I knew, of course, that her claim couldn’t be true. The 把 construction is a super-common feature of spoken Mandarin, and there’s no way that native speakers aren’t using it on a regular basis. Sure, it’s possible to eliminate it in order to simplify one’s speech, but this client was claiming that the people around her weren’t using it at all. But her feedback actually highlighted an important truth: she wasn’t hearing the 把 construction at all.

And this is one of the things that most fascinates me about grammar: when you’re ready to learn a new grammar point, it will naturally come into focus. Little connector words that you didn’t even hear before will suddenly start to stand out. Although you were once happy to just get the basic gist, your brain will start to hunger for a more precise understanding of the grammar point in question.

When you start to get those “grammar pangs,” that’s when you need to go to your grammar resource, whether it’s Claudia Ross’s Modern Mandarin Chinese Grammar printed on a dead tree or the Chinese Grammar Wiki. They say of food that “hunger is the best sauce.” The same is true for grammar. To do otherwise is to invite indigestion.

Thanks, John! I’m sure my readers found this article as interesting as I did. Personally, I think the most important part of your article is the last two paragraphs. Learning grammar based on what you intuitively feel that you need to know has been a guiding principle for me as well. Naturally, this goes both for understanding grammar and for using it yourself. The most powerful way of learning anything is to have an actual need for it before you learn it! If you want to know more about John, head over to Sinosplice and bookmark/subscribe; if you want to learn more about grammar, head over to the Chinese Grammar Wiki!

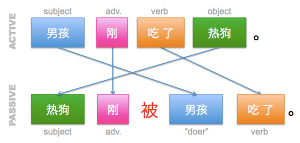

Image credit: All images used in this article are from the Chinese Grammar Wiki and are reproduced with explicit permission.

11 comments

Thanks for the article John! I must admit grammar is the one thing I feel I need most at this point in my journey, yet it’s also the thing I can usually least be bothered to do when I sit down to learn Chinese.

When I first started I went with an input and usage approach and it seemed to work well and I progressed quickly. However after a while I began to stagnate. I think using an input and usage based approach our brains will acquire what is simple and easy to acquire. Less obvious grammar patterns and rules, however, need to be pointed out to us in order to be acquired. Our brains seem to want to do what is possible in our first language and we need to be made aware what isn’t possible with either negative feedback or descriptive rules.

Although my grammar still needs a lot more work. Two things have seemed to work for me so far.

1) Writing, especially using website like lang-8, seems to be a great way of eliciting feedback, at least more than spoken conversations where people are reluctant to interrupt a person mid sentence to correct grammar mistakes. The extra feedback and planning time that goes into writing seems great for grammar.

2) Learning rules and reading more, although learning rules has always been a common way of learning grammar for me it is only really useful when paired with a lot of reading. Examples of certain structures really seem to pop out of input when you do learn a few rules and structures on the side. Just try to read more intensively and think ‘why is this written like this?’ Consider what affect the grammar has on meaning.

I agree grammar is much more interesting when you learn it as it is needed.

You’re welcome! I’m glad you liked it.

I loved this part of the article, it made me laugh, because it’s so true:

“They say of food that “hunger is the best sauce.” The same is true for grammar. To do otherwise is to invite indigestion.”

No one wants grammar indigestion! Ugh. 🙂

What I find the most frustrating is a lack of grammar exercises. As a non native speaker, at the moment when I was learning English, I’ve had hundreds of books, websites, etc. Which included many exercises, especially focusing on little details between two similar, yet different patterns.

I’d love to have a book like that. Learning grammar would way easier.

Excellent article, but I’m wondering if you’re confusing the word input with output — “input” in the taking in of new vocabulary and patterns in the cognitive act of “acquisition” of new language; “output” is the way learners use language items in their own speech or writing.

Thanks for sharing these thoughts on learning Chinese, both here and elsewhere in your blog.

Perhaps John can answer this himself, but as far as I can see, there is no confusion here. Input usually refers to listening and reading, which is what I think he means in this article. Perhaps you could be more specific so we can sort out the misunderstanding?