Flashcards; some people love them, some people hate them. The goal of Hacking Chinese is to go beyond black and white and figure out how things work so we can get the most out of them.

Flashcards; some people love them, some people hate them. The goal of Hacking Chinese is to go beyond black and white and figure out how things work so we can get the most out of them.

This is the third and final article in a short series focusing on flashcards. I will summarise the major pros and cons below, but for full details, please check out the first two articles. You can read this article without having read the previous two, however.

- Why flashcards are great for learning Chinese

- Why flashcards are terrible for learning Chinese

- How to best use flashcards to learn Chinese (this article)

In this article, my goal is to help you figure out whether or not you should use flashcards for learning Chinese, how much you should rely on them and for learning what things.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

Pros and cons of using flashcards to learn Chinese

In the first article in this series, we looked at the benefits of using flashcards for learning Chinese. What it boils down to is that flashcards are very efficient (much bang for your buck) when it comes to learning certain aspects of the language. No other method will allow you to learn so many words so quickly with so little effort while being confident that you will remember most of them.

The main drawback with flashcards is that they isolate and simplify to a point where many of the skills you need to be able to use Chinese proficiently in the real world aren’t practised. Knowing characters in your flashcard app does not equate to good reading ability, and being able to recognise spoken words in isolation doesn’t transfer well to real-world listening either.

The major argument against flashcards is that if they are so flawed, why not do the real thing and listen, speak, read and write Chinese instead? Can’t you learn Chinese simply by using the language?

Can you learn Chinese without using flashcards?

You can certainly learn Chinese without flashcards. I think it’s safe to say that most people who have become proficient in Chinese haven’t relied on flashcards, and that’s probably true even if we don’t count native speakers, who rarely use flashcards.

The only serious alternative to flashcards is large amounts of comprehensible input paired with meaning-focused communication. I’ll talk more about this later because it’s something you should do regardless if you’re using flashcards or not, but in short, you rely on the same principles that make flashcards work: spaced repetition and active recall.

If you think about it, reading and listening are also spaced repetition, but with some added benefits. By reading and listening a lot, you will encounter vocabulary you need to review over and over, so you will learn it. The only difference is that it’s not as systematic and therefore requires more time than using a flashcard app. The extra time is not wasted, however, but well-spent on listening and reading, which you should do anyway.

Similarly, when you use Chinese to communicate in speaking or writing, you need to actively recall the vocabulary you have previously learnt. This is also less systematic than using a flashcard app but again comes with many other benefits. For example, since you constantly need to recall the meaning of words even if you know them, you increase how quickly you can do it, building your fluency, which I will also return to later in this article. This won’t happen with spaced repetition software, where seeing a word a few dozen times is considered a lot, compared to seeing common words hundreds of times in a longer text.

Native speakers don’t need flashcards to learn commonly used vocabulary in their native language because they listen and read so much. They eat such a varied and rich diet that there’s no need for supplements, in other words. When they do use flashcards, it’s usually for memorising domain-specific terminology, such as when going to medical school.

Just because you can avoid flashcards entirely doesn’t mean that you should

Just because you can use massive amounts of listening and reading and avoid flashcards entirely, it doesn’t mean that it’s the most efficient way to learn for you, however; many of the benefits I mentioned in the first article in this series are highly relevant to most people reading this article. It’s also important to realise that your learning situation is likely different from that of a native speaker, so their doing well without flashcards isn’t always relevant.

A good example of this would be writing Chinese characters by hand. Children in China earn this largely without the aid of flashcards, but they do so in a way that is prohibitively time-consuming for the average adult language learner. There is simply no way that you’ll be able to replicate what they go through in school at home, so if you want to learn to write characters by hand, you need a more efficient method, and flashcards and spaced repetition are uniquely well-suited for this, as I have argued in this article: Why spaced repetition software is uniquely well suited to learning Chinese characters

Why spaced repetition software is uniquely well suited to learning Chinese characters

So yes, of course, you can learn Chinese without flashcards, but that doesn’t mean that you always should. The interesting question is in which cases the pros outweigh the cons, making it worthwhile to use flashcards.

What should you use flashcards for?

Here are a few things I think you should consider carefully before discarding. These all draw heavily on the advantages of flashcards while avoiding most of the disadvantages.

As a stepping stone to more reading – One of the major challenges when learning to read in Chinese is the large number of unknown characters and words. Before I reached a decent reading level in Chinese, I relied on flashcards to boost my passive understanding of written characters and words. This is much less time-consuming than focusing on handwriting, as you can blaze through reviews. The idea here is to rely on flashcards to learn the basic meaning, and then read extensively to learn how the vocabulary is used. Do not pursue this approach without also reading a lot!

As a stepping stone to more reading – One of the major challenges when learning to read in Chinese is the large number of unknown characters and words. Before I reached a decent reading level in Chinese, I relied on flashcards to boost my passive understanding of written characters and words. This is much less time-consuming than focusing on handwriting, as you can blaze through reviews. The idea here is to rely on flashcards to learn the basic meaning, and then read extensively to learn how the vocabulary is used. Do not pursue this approach without also reading a lot! To learn to write characters by hand – As mentioned already, flashcards and spaced repetition are uniquely well-suited to learning to write Chinese characters by hand. However, before you go ahead and learn to write 5,000 characters by hand, you should consider how much handwriting you need. In the modern, digital world, handwriting is of little practical value, so learning to write by hand everything you can read is almost certainly a mistake. My suggestion is to learn a core set of characters by hand and focus on reading and typing for the rest.

To learn to write characters by hand – As mentioned already, flashcards and spaced repetition are uniquely well-suited to learning to write Chinese characters by hand. However, before you go ahead and learn to write 5,000 characters by hand, you should consider how much handwriting you need. In the modern, digital world, handwriting is of little practical value, so learning to write by hand everything you can read is almost certainly a mistake. My suggestion is to learn a core set of characters by hand and focus on reading and typing for the rest. To nail exams in a formal course – If you’re in a course that tests your explicit knowledge of vocabulary and you care about your grades, you should use flashcards. You don’t need to rely on them for everything, but there simply isn’t a more efficient way to ensure you know how to write characters by hand, give definitions of words and write out the Pinyin on an exam. For long-term learning, you should also use spaced repetition, but remember that cramming with flashcards can be a viable option in the short term. You don’t have to use flashcards with long-term spaced repetition. The obvious caveat here is that a formal course that assesses your Chinese proficiency by testing explicit vocabulary knowledge probably isn’t very good.

To nail exams in a formal course – If you’re in a course that tests your explicit knowledge of vocabulary and you care about your grades, you should use flashcards. You don’t need to rely on them for everything, but there simply isn’t a more efficient way to ensure you know how to write characters by hand, give definitions of words and write out the Pinyin on an exam. For long-term learning, you should also use spaced repetition, but remember that cramming with flashcards can be a viable option in the short term. You don’t have to use flashcards with long-term spaced repetition. The obvious caveat here is that a formal course that assesses your Chinese proficiency by testing explicit vocabulary knowledge probably isn’t very good. To conquer new areas of the language – If you’re no longer a beginner and find yourself in a situation where you need to be able to rapidly expand your Chinese into a new area, flashcards can be a great supplement to reading and listening more. For example, when I started studying phonetics in Chinese, I needed to learn a few hundred words specific to that area of study. Yes, I could have learnt that by reading books, listening to lectures and so on, which I also did, but flashcards helped me learn the words quickly. Sometimes, it can also be very difficult to find the reading and listening material, such as when I started practising gymnastics in Chinese and wanted to learn key vocabulary. I collected important words and expressions from my coach and teammates and used flashcards to make sure I didn’t forget them. Learning this by pure exposure would have taken a long time.

To conquer new areas of the language – If you’re no longer a beginner and find yourself in a situation where you need to be able to rapidly expand your Chinese into a new area, flashcards can be a great supplement to reading and listening more. For example, when I started studying phonetics in Chinese, I needed to learn a few hundred words specific to that area of study. Yes, I could have learnt that by reading books, listening to lectures and so on, which I also did, but flashcards helped me learn the words quickly. Sometimes, it can also be very difficult to find the reading and listening material, such as when I started practising gymnastics in Chinese and wanted to learn key vocabulary. I collected important words and expressions from my coach and teammates and used flashcards to make sure I didn’t forget them. Learning this by pure exposure would have taken a long time.

As should be clear by now, flashcards work best when integrated into a balanced approach to learning Chinese in general. They should be supplements to a well-rounded diet, not the main course. This means that to understand how to use flashcards, it’s necessary to zoom out a bit and look at what other things you should be doing as well.

How much of a balanced approach to learning Chinese consists of flashcards?

The main problem with relying too much on flashcards is not that they are bad in themselves, but rather that they take time away from activities that might be more useful. If you spend all your days staring at a flashcard app, you’ll be missing other learning opportunities. Flashcards can be good for your Chinese, but many other things are more important.

The most useful framework for balancing language learning activities is Paul Nation’s four-strands model. As described briefly in the previous article in this series, three of the four strands are about meaning-focus activities where the goal is to convey or receive real information, not artificially practise aspects of the language, as with flashcards.

Analyse and balance your Chinese learning with Paul Nation’s four strands

This confines all activities that focus explicitly on the Chinese language, such as learning about grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, characters and so on, to a combined total of one-fourth of your total study time. It could be argued that it should be less, but I feel confident in saying that it shouldn’t be more.

It’s hard to quantify how much you should spend on the other language-focused activities mentioned in the previous paragraph, but it seems reasonable to say that flashcards shouldn’t make up more than 10% of your study time on average. If you have some specific reason to go above that for a short period, fine, but that should be an exception, not the rule.

What if you hate flashcards? Should you use them anyway?

One downside with flashcards that I didn’t mention in the previous article in this series is that some people find them mind-numbingly boring. Others just find them tedious but are willing to put up with them because of the benefits they bring. Few love reviewing flashcards, even if I have run into such people, too. I’m somewhere in the middle myself.

How much you like flashcards, regardless of their other pros and cons, is an important factor to take into consideration. If you hate flashcards, the default approach should be to not use them. If you force yourself to use them, you risk demotivating yourself, which will impact other areas of learning as well. A method can only be good if you’re willing to use it, after all. I explored this problem in more detail here: Should you use an efficient method for learning Chinese even if you hate it?

Should you use an efficient method for learning Chinese even if you hate it?

If you only dislike flashcards, rather than hate them, you might still use them for some specific things if your study situation calls for it. For example, if your course requires you to be able to write lots of characters by hand, it might be worth using flashcards only for this specific application, as most other options are highly inefficient. You might even be able to tweak your flashcards in a way that makes it more fun. Try out Skritter if you haven’t already!

What things are more important when learning Chinese than flashcards?

To figure out what you should use flashcards for and what you should use other methods for, let’s consider what you need to learn a language in the first place. This is a huge topic that doesn’t fit neatly into a short list, but I’ll do my best, drawing on Paul Nation’s four strands again:

Meaning-focused input is when you listen and read with a high level of comprehension with the goal of understanding, as opposed to learning new words, grammar and the like. Your textbook probably does not count (it’s too hard and focuses on teaching you vocabulary and grammar), but a graded reader or other text at an appropriate level might work. Listening recommendations for all levels can be found here, and reading recommendations for all levels can be found here.

Meaning-focused input is when you listen and read with a high level of comprehension with the goal of understanding, as opposed to learning new words, grammar and the like. Your textbook probably does not count (it’s too hard and focuses on teaching you vocabulary and grammar), but a graded reader or other text at an appropriate level might work. Listening recommendations for all levels can be found here, and reading recommendations for all levels can be found here.- Meaning-focused output is when you speak and write to communicate using mostly language you already know. Speaking drills and writing example sentences don’t count, but talking about topics familiar to you does. Writing a diary also counts. Naturally, meaning-focused input and output are combined in conversations, so I’m not saying you have to keep them separate!

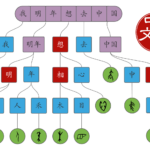

Language-focused learning includes everything that focuses on the language itself, including, but not limited to, flashcards. I’m mentioning it here not because you should use flashcards more, but to remind you that there are other things you might want to consider doing as well, such as learning the fundamentals of pronunciation, reading articles on Hacking Chinese, tuning into my podcast or maybe learning more about how characters work.

Language-focused learning includes everything that focuses on the language itself, including, but not limited to, flashcards. I’m mentioning it here not because you should use flashcards more, but to remind you that there are other things you might want to consider doing as well, such as learning the fundamentals of pronunciation, reading articles on Hacking Chinese, tuning into my podcast or maybe learning more about how characters work.- Fluency development is about getting better and faster at what you already know. This is often neglected by students and teachers alike, and it’s common to think that if you’re not constantly learning new characters and words, there’s something wrong. Nothing could be further from the truth. Being good at using what you have already learnt is crucial when using Chinese in the real world! Read more about fluency development here.

How to best use flashcards to learn Chinese

Now that we approach the end of this series of articles focusing on flashcards, it’s time to get more practical and try to answer the question of how you should use flashcards to learn Chinese. As we have seen, there are many factors to consider, so no single answer that I give will work for all students reading this, but I’ll give you an idea of how to get started:

- Consider why you are learning Chinese, both in the short and long term

- Write down what knowledge, skills and abilities you need to reach your goal

- Compare your list with the four strands to make sure everything is covered

- Look at my list of suggested uses for flashcards and evaluate each one

- Note which uses flashcards might have in your overall learning strategy

- Try different apps to see how well they align with your strategy

- Be mindful to not use flashcards too much

- Keep updating how you use flashcards as your level increases and your situation changes

Different people will come to different conclusions after going through these steps.

Some of you will conclude that extensive reading and listening is better than flashcards, which is great.

Others will stick to using flashcards for specific applications, such as making sure they get good grades or know how to write characters by hand. That’s great, too.

If you rely on flashcards much more than I suggest here, you’re not necessarily doing something wrong, but I do hope that this series has at least given you pause for thought!

How do you use flashcards to learn Chinese?

The goal of this series of articles has been to explore flashcards as a tool for learning Chinese. As usual, I’m not interested in quick and easy answers, because they are often wrong. Instead, whether or not flashcards are good for learning Chinese depends on many factors, many of which are unique to you and your learning situation.

Thus, to broaden the scope a little, I invite you to share your approach to learning Chinese and which role, if any, flashcards play in it.

- How do you use flashcards and how is it working out for you?

- If you’ve been learning Chinese for a while, how has this changed over time?

- Did you dislike flashcards, but then came to like them?

- Did you rely on flashcards a lot initially, only to phase them out later?

Leave a comment below and let us discuss!