While strong motivation doesn’t necessarily accelerate your learning or improve your memory, without it you won’t spend enough time learning Chinese. This is particularly true in the long run!

While strong motivation doesn’t necessarily accelerate your learning or improve your memory, without it you won’t spend enough time learning Chinese. This is particularly true in the long run!

People who fail to learn Chinese do so because they give up, not because they keep trying without succeeding.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode #188:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

The reason is that learning a language is difficult in the sense that walking a thousand miles is difficult, not climbing a wall. Each step is easy, but the difficulty comes from the number of steps you need to take.

So how do you keep walking, week after week, month after month, year after year?

Learning Chinese after the initial spark of interest

If you started learning Chinese because you wanted to, rather than being forced to by circumstances, you started with a strong motivation to learn. Some of you may still surf that wave of initial motivation, which is great! Use it while it lasts.

However, for most people, the initial motivation to learn Chinese sooner or later ebbs, and you need to find other ways to keep going. It’s rare to keep thinking that the language is fascinating enough to keep you up at night for years. This drop in motivation often coincides with reaching the intermediate plateau, where it feels like you’re not making progress anymore, no matter how much you study. It can also happen before that, or later, depending on your situation.

Human motivation and Self-Determination Theory

Questions about what drives us and makes us behave the way we do have always interested me, and it’s something I think all people think about occasionally. Why is it so hard to do the things we tell ourselves that we want to do? Why do we often do other things instead?

Motivation has also been researched for a long time and there are several models to explain what drives us to learn a language. The most well-known one is probably Dörnyei’s motivational theories, such as the L2 motivational self system, which I will return to in another article (see Dörnyei, 2009, for an overview).

In this article, I’m instead going to focus on a framework called Self-Determination Theory (SDT), developed by Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan (1985), and since further researched and developed by a large number of researchers, including those looking into second-language motivation (McEown & Oga-Baldwin, 2019).

While SDT was not developed specifically for language learning, it’s a framework that I useful when talking both with students and teachers about motivation. I first stumbled upon it many years ago and have since incorporated it in several of my professional development courses at university. It has thorough experimental backing and is easily applicable to many different situations.

Intrinsic motivation lasts longer than extrinsic motivation

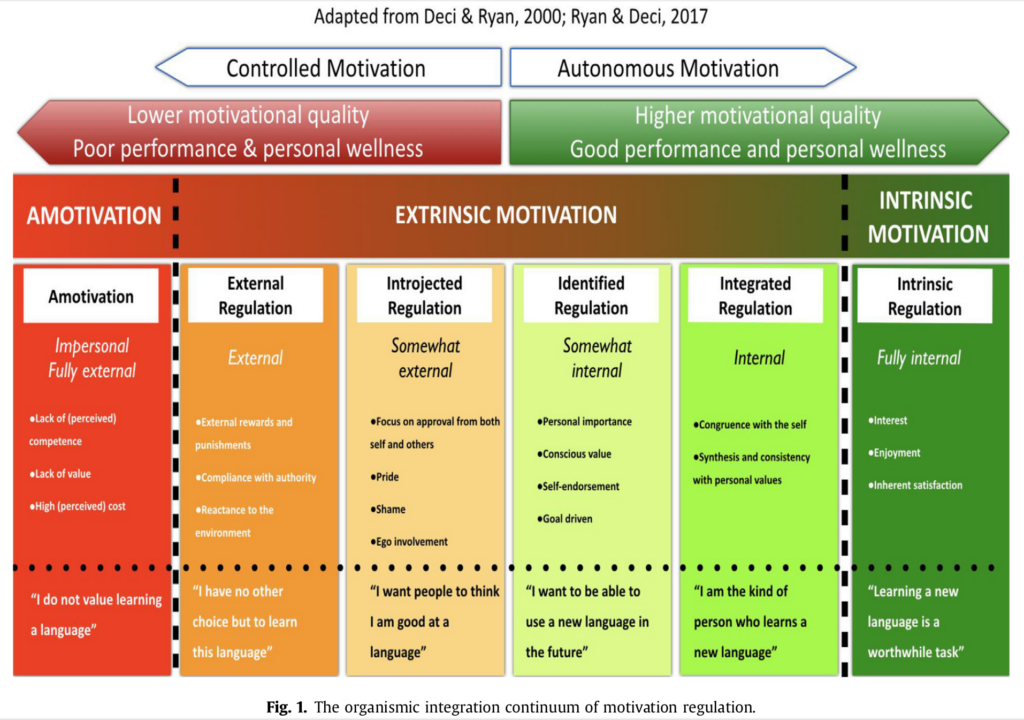

The core of SDT is that people are driven by three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. These are universal and, when satisfied, create not just intrinsic motivation, but also psychological well-being in general. The opposite of intrinsic motivation is extrinsic motivation, such as external rewards or punishments, and compliance with authority. The following figure is from McEown & Oga-Baldwin (2019) p. 5 (the full article is available online here):

A fundamental focus of research within SDT is this dialectical between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation; indeed, it was research into this area that spawned the whole framework more than forty years ago. In general, it has been found that extrinsic motivation can work, but intrinsic motivation tends to last longer.

This probably matches your own experiences, as I think most of us can find examples where we have been driven to do something mostly to get good grades, earn some extra money or impress someone, but where this type of motivation is often short-lived. Yes, we need to work to earn money to survive, but beyond that, external rewards can only do so much.

Compare this with socialising with people you love or indulging in your favourite hobby. These are activities you engage in because you enjoy them for their own sake, not to reap an external reward or because you’re forced to.

Stay motivated to learn Chinese in the long term by focusing on basic psychological needs

SDT consists of several components, and discussing all of them in relation to learning Chinese would require a medium-sized book, so in this article, I’m going to focus on only one component, Basic Psychological Needs Theory, and see how they can help us understand what motivates us and what can power a life-long journey to learn Chinese.

Here are the three basic psychological needs:

- Autonomy is about being in control of your learning situation and your actions within it. For independent learners, this is rarely a problem, but if you’re locked into a course with a curriculum that doesn’t closely match your own goals for learning Chinese, or if you have a teacher who makes all the decisions for you, autonomy can be severely lacking. This is one of the major issues in formal education.

- Competence is about feeling that you’re able to operate effectively within the activities you perform. This is only indirectly linked to language proficiency, as how competent you feel is much more about the tasks you engage in and your expectations, not how good your Chinese is on some kind of objective scale. As some teachers are fond of saying, it’s not about how difficult the language is, but what you ask students to do with it.

- Relatedness is about connecting with other people and finding meaning through social relationships. This can be with your teacher, fellow learners or with native speakers of Chinese. The desire to fit into a social situation, integrative motivation, can be powerful, but also elusive if you’re studying in your home country.

So, to keep motivated in the long run, it’s important to pay attention to these psychological needs and make sure they are met as far as possible. Naturally, one need might be more important for you than others, so learning about what motivates you is part of the process!

Let’s have a look at each need and see what it means for learning Chinese, and also what can happen if you don’t meet it.

Staying motivated to learn Chinese by focusing on autonomy

As mentioned already, how autonomous you can be depends on the situation in which you’re learning Chinese. If you’re not enrolled in a course and can do whatever you want, autonomy is rarely an issue, so I will skip this in the present discussion. If you’re learning independently, you can skip this section.

Even though I think all students should strive to be as independent as possible, it’s common, even advised, to be enrolled in some kind of course, even if that shouldn’t be the only thing you’re doing. When studying Chinese in a formal educational setting, it’s important to take control of your learning. You should not outsource this to your teacher or curriculum designer, even though you need to heed those too, especially if you want good grades. But simply following a course and doing what you’re told won’t cut it.

Should you enrol in a Chinese course or are you better off learning on your own?

To foster autonomy, you need to know what you want. I suggest that you write down your own goals for learning Chinese and what skills you need to reach those goals, and then compare that with the objectives specified in your curriculum, as well as the activities you engage with in class.

Then ask yourself the following questions:

- Which skills and areas are covered by this course?

- Which areas do I need to focus on on my own?

- How can I adjust my learning to reach my goals?

If you want more advice on how to do this, you can check either Unlocking Chinese: The Ultimate Course for Beginners, or Hacking Chinese: A Practical Guide to Learning Mandarin. The former is, as the name implies, for beginners, and the latter is for everyone else.

You can also try to boost autonomy even in situations where most things are controlled by someone else. You can often choose how to study, and you can try to tweak your learning experience as much as you can in your favour. Autonomy is mostly about real choice, so things like choosing to write a character in blue instead of green probably don’t make you more autonomous, but do whatever you can!

Staying motivated to learn Chinese by focusing on competence

The more I learn and teach Chinese, the more I realise how important it is to manage the difficulty of learning activities. If you make activities too hard, most people lose interest as they are not able to complete the tasks and feel bad about their inability to do so.

Naturally, this is not limited to formal education, and simply being unable to communicate what you want in Chinese doesn’t feel good. The worst case of this is when you study Chinese for a long time, but when you try to use it with native speakers, they just look confused and switch to English. Read more about that here: Why your Chinese isn’t as good as you think it ought to be.

As mentioned earlier, one way to increase the feeling of competence is to limit the activity. Focusing on a smaller part of the language makes it easier to master the skills needed to function in that area. Beginners should learn Chinese in Chinese as early as possible. Feeling that you can use the language you learn is motivating! More advanced students can rely on things like narrow reading and listening to limit the language to feel that they are making progress in that limited area.

Feeling competent is also a matter of managing expectations. If you think that you’ll be able to learn Chinese as quickly as you’ve learnt Spanish, or that you will reach a near-native level in two years, you’re going to feel bad about your studies almost from day one.

You can also lower the expectations, which sounds weird at first, but hear me out! I use this often when teaching Chinese through games and it works well. In a game where you try to make your teammates guess the right word by describing it indirectly, simply having a time limit will decrease expectations of accuracy; no one will produce perfect sentences if speed is important.

In general, focusing on fluency development, where you rely almost entirely on what you already know, is great for nurturing competence. If your learning activities always involve tons of unknown words or grammar, you will perform worse and feel less competent.

Feeling competent is important not just for language difficulty, though, it’s also true for study management. If you set goals that are too lofty and you often fail, this might make you less motivated to try again. On the other hand, if you set goals that are too easy, you won’t feel much when you achieve them either. Realistic goals that you need to work hard for is the way to go.

Staying motivated to learn Chinese by focusing on relatedness

Humans are social beings and our relationships with other people are important. This can be used to boost your Chinese learning in many different ways. Here are some ideas based on who the other person is. Note that these are not mutually exclusive.

- Fellow students – You are not the only person learning Chinese, definitely not globally, but probably not locally either. Teaming up with a classmate or finding a study buddy online can be great for motivation. You share the same goals and face the same challenges, and sharing these strengthens not just your relationship, but also your motivation to keep learning Chinese. Peer pressure can be a good thing, too, so enrolling in a course above your level can create a strong urge to improve to fit in, although this might also hurt your feeling of competence. Learning with others can provide mutual accountability, encouragement and a sense of community.

- Chinese teachers – Who your teacher is and how you relate to them can have a large impact on your motivation to learn. With the right teacher, you feel safe, learning is fun and the journey ahead feels manageable. I think teachers who are second language learners have an added benefit here in that students often feel that it’s more realistic to become like them; if the teacher learnt Chinese as an adult, so can I! That being said, a good teacher-student relationship can be very motivating, regardless of how the teacher learnt Chinese. If you don’t feel that you can relate to your teacher, find another one, if possible.

- Native speakers – Communicating with native speakers is one of the main reasons for learning Chinese, but socialising and forming relationships of different kinds with native speakers is also one of the most powerful motivations to keep learning. If you live in a Chinese-speaking environment, gaining access to and functioning in social contexts can be an extremely powerful drive to keep improving, but getting to know and make friends with individual people is also highly motivating. Naturally, socialising in Chinese, even with a single person, will be exhausting at first, but as your Chinese improves, you’ll be able to gain more energy from these interactions than you put into them.

I have written more about the importance of social learning here: You shouldn’t walk the road to Chinese fluency alone

Satisfying basic psychological needs and reaching your goals of learning Chinese

Before wrapping up this article, it’s worth noting that Basic Psychological Needs Theory is a great tool to analyse your learning situation with the ultimate goal of boosting your motivation, but there can also be a conflict between psychological well-being and reaching your goals for learning Chinese.

Let me explain by showing a few examples:

- Focusing on autonomy is not easy. Being responsible for your learning takes time and energy, and the fact that you are the one making the important decisions might make you autonomous, but if you make the wrong decisions, this won’t be beneficial for your Chinese. Being in control is great when you know best, such as which way of doing something you find most enjoyable, but not so great when one option is strictly better than another, but you’re ignorant of this.

- Focusing on competence can be used as an excuse to avoid challenging yourself. The reason learner Chinese podcasts contain so much English is that it makes the listeners feel safe, but you’re certainly better off focusing on content which is mostly in Chinese, even if this will make you feel less competent. Furthermore, you need to make sure that the way you evaluate your competence matches your goals because while nailing dictation tests and getting good grades will make you feel competent, these activities might be only indirectly related to your ability to use Chinese in the real world.

- Focusing on relatedness has similar drawbacks if you overdo it. The most egregious mistake you can make as an exchange student or expat is to hang out with other foreigners too much. Yes, indeed, you shouldn’t travel the road to Chinese mastery on your own, but you shouldn’t camp out on the side of the road with your buddies drinking beer either. Similarly, being on too friendly terms with a teacher might mean that they take their teaching role less seriously, something I often hear students complaining about.

Still, paying attention to the three psychological needs of competence, relatedness and autonomy is a great way to ensure long-lasting motivation. I wanted to mention possible downsides because the goal of Self-Determination Theory is not to teach you Chinese but to understand human behaviour and psychological well-being. Naturally, I also want you to feel good, but the goal here is to do that while also helping you to reach your goals for learning Chinese!

For more about how to truly master Chinese in the long term, check out: The three roads to mastering Chinese.

References and further reading

Davis, W. S., & Bowles, F. (2018). Empowerment and intrinsic motivation: A self-determination theory approach to language teaching. CSCTFL Report, 15, 1-19

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York: Plenum.

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self system. Motivation, language identity and the L2 self. Multilingual Matters

McEown, M. S., & Oga-Baldwin, W. Q. (2019). Self-determination for all language learners: New applications for formal language education. System, 86, 102124.

Printer, L. (2020-2024). The motivated classroom podcast. Available here.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford Press