All serious learners face the same problem: Regardless how diligent we are and how efficient our studying is, there are only 24 hours in a day. This is a fact and there’s nothing we can do about it. Therefore, one cornerstone of learning a language quickly is to examine the time you have available and see how you can fit as much language learning as possible into your day without burning yourself out.

This is a process that requires both experience, diligence and a deep knowledge of oneself. Not only do you need to find out where you have time and how to use it, you also need to make sure you’re having fun, lest you’ll burn yourself out and end up giving up language learning altogether. There is a mechanical, analytical side to it which is tricky to master if you start from scratch. So far, I’ve written the following articles about this part of the process:

- The time barrel: Or why you have more time than you think

- Time quality: Studying the right thing at the right time

- Learning efficiently vs. learning quickly

However, it’s essential to remember the human side of it, which includes keeping track of your energy levels, making sure that you’re studying the right thing according to your current state. As mentioned above, you also need to have fund and actually enjoy what you’re doing. Studying isn’t only what’s going on in a classroom, it can be anything that helps you along the way toward Chinese mastery.

- Study according to your current productivity level

- Enjoying the journey while focusing on the destination

- Diablo 3 and Starcraft 2: Playing computer games in Chinese

Fortunately, I have some great news for you. For the past six months, I have conducted some pseudo-scientific experiments on my own learning. I can say for sure that the method I will describe below worked well for me, but I can’t guarantee that it will work for others (hence the pseudo). If I can convince my adviser, I will write my master thesis about this next year. This article is just a brief, personal summary to let you in on what I’ve been doing recently. Hopefully, it will also help you master Chinese faster.

Lucid dreaming

Before I get into the details of the method, I’d like to give you some background information. I started experimenting with lucid dreaming about five years ago. If you’re not familiar with lucid dreaming at all, it’s a kind of dream in which you are fully aware of the fact that you’re dreaming and your mind works very much like it does when you’re awake.

For instance, when you’re in a lucid dream, you know that you’re dreaming, you can think about things going on in the waking world (such as what you did yesterday or what you plan to do after you wake up). In fact, everything is pretty much like being awake, except the fact that you’re dreaming.

Now, this sounds pretty weird, but it has been scientifically proved several times. From a scientific point of view, the problem with lucid dreaming was that it was all based on people’s subjective memories of dreams. People saying that they were aware of dreaming and even being able to control their dreams doesn’t mean that it’s true. This changed in the 1970s. Perhaps the most famous experiment was conducted by Stephen LaBerge of Stanford University, who used a clever design to prove that lucid dreaming is a real phenomenon. The design was based on one used by Keith Hearne a few years earlier.

In their experiments, lucid dreamers were able to communicate with the scientists while they were dreaming (eye-movements in dreams match those that can be seen in people in REM-sleep). For instance, they agreed beforehand what up, down, right and left meant and the test subject was then able to communicate with the scientist using combinations of eye-movements.

Lucid dreaming is a skill that can be learnt. The process is relatively simple and involves several steps, such as first practising remembering dreams, then focusing on conscious awareness of dreams, then on controlling them. With some practice, it’s not hard to reach a level where you can have lucid dreams whenever you want to and be able to exert a high degree of control over the content of these dreams.

Lucid dreams of foreign language mastery

This is all very cool (at least I think so), but what’s it got to do with learning Chinese? I have spent some serious time looking into lucid dreaming and have learnt a lot (both in theory and practice). If you’re interested, I suggest you check out these forums: Dream Views, World of Lucid Dreaming.

Now, the really cool things started happening a few years ago when I started dreaming in Chinese. After waking up, I could remember what words and sentences I used in the dreams. I could even remember myself correcting my own grammar, and, upon waking, realising that my corrections were perfectly legit!

This only happened occasionally, though. The next step was to do this deliberately. I took up lucid dreaming again and started experimenting. Since I have already learnt Mandarin to a reasonably advanced level, it wasn’t really a good for testing this new method. Instead, I turned to Japanese, which I didn’t know much about when I started the experiment six months ago. I now know quite a lot of Japanese, but more about that later.

Input vs. output

It’s obvious that we can’t acquire new information when dreaming. As far I know, there is no way of communicating with someone who is in a lucid dream (or a normal dream for that matter), so you can’t just put a recording of Chinese sentences on play next to your bed and hope to learn them while sleeping. However, we can still practise speaking (and perhaps writing) while asleep.

Stephen Krashen has argued that output is the result of learning rather than learning itself. I think this is true, but only up to a point. He’s right that we don’t actually learn many new things by speaking, but I do think it’s fairly obvious that the only way to become fluent is by using that which we already know and becoming really good at it. Fluency isn’t necessarily about knowing a lot, it’s about being able to use what we have smoothly and efficiently.

Enter: Lucid dreaming. What if you could have several extra hours of practice everyday without removing time from any of the other projects you’re working on? This won’t teach you new words, but you can still review and master sentences you already do know. For instance, you can practice talking about specific topics (either prepared or unprepared). You can also go through and review things you’ve learnt recently. You can practice for oral exams or presentations.

However, you won’t receive any reliable input. There might be Chinese native speakers in your dreams, but they are only constructs of your own mind. Their Chinese ability is limited to your own ability. There might be something cool buried here if it turns out that you subconsciously know more Chinese than you can actually produce. Thus, the native speakers in your dreams might actually be better at Chinese than you are when you’re awake.

The experiment

As I said above, I used Japanese for this experiment to make sure I entered into unknown territory (I knew about ten words in Japanese before this experiment). If you want to try this, you can of course do it with any language. There should be many variations of this experiment, this is just a brief summary of what I did. The most basic form of practice is reviewing sentences and it was the first experiment I did:

- Study a few sentences in the target language

- Review them once before going to bed

- Practice using them while in a lucid dream

- Try to create interesting and entertaining contexts

- Repeat

I tried this with a normal Japanese phrase book I picked up in a second-hand bookshop close to where I live. After going through a few iterations of the above process, I reached a stage where I could read a few phrases I had never seen just before going to bed, and then review and use those sentences while sleeping. Upon waking up, I was able to remember most of the sentences.

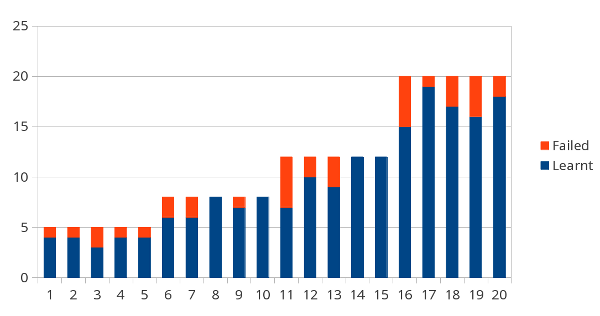

This is a skill that takes time to learn. This is what my progress looked like (it took me a while to learn the lucid dreaming part of the experiment, so the actual Japanese part only started seriously a month ago):

As you can see, I increased the number of phrases to learn incrementally (5, 8, 12, 20) and recorded the results. For practical reasons, I wasn’t able to do this every night, but all twenty experiments were carried out in roughly forty days. After the initial learning phase, I reviewed old patterns and words on a less systematic basis (while dreaming, of course), but a test I did last week shows that I remembered 178 out of the 225 sentences I tried to learn. This is after spending five to ten minutes each night just before going to bed, the rest of the time was spent while dreaming (hard to measure).

Now, the important thing here isn’t that I didn’t learn these sentences just passively. Since I have spent considerably amount of time actually using the sentences I know them very well by now, just as if I had spent that amount of time using them “in real life”. Obviously, I receive no feedback on my pronunciation, but if I really want to learn Japanese, I’ll get that from a tutor.

Sort of speaking to yourself, but not really

Now, sceptics might say that this is the same as repeating what you have learnt to yourself. And you’d be (mostly) right. However, repeating what you have learnt during the day while you’re sleeping in a manner that allows you to remember it the next day is incredibly useful and has huge potential. I’m just scratching at the surface here.

There is another difference between this method and speaking to yourself, though. If you sit down in front of your desk and read phrases in a foreign language, you will get bored fairly quickly. If you can create an interesting dreamscape and use the phrases in real situations, it will be much more fun. Research has shown clearly that we’re more likely to recall things we have learnt if the learning situation matches the recall situation. Thus, if we practice asking the price of a cup of coffee in a café, it will be easier to recall that phrase while in a café compared to when scuba diving.

So yes, it’s a bit like talking to yourself, but I think there’s more to it than that. Even if it’s just like talking to yourself, you can still practice fluency and review what you have learnt throughout the day, without spending more of your precious waking time.

Towards a more lucid future

I will continue to do research in this area. If you’re interested in participating, let me know! It would be useful if you’re already familiar with lucid dreaming and have reasonable control of your lucid dreams already. If not, that’s okay too, but rather than asking me for beginner help, I suggest you head over to the two forums I linked to above.I used guides there to get started many years ago and I know that they work.

Once you’ve learnt the basics, I’ll gladly take you on as a student (read: disciple). I haven’t decided on a price yet, but since this is quite unique and will help you tremendously, people who apply should be prepared to compensate me for the time I have invested. Like most other schemes, I might then increase the price for each subsequent level and once you’ve earned the grandmaster diploma (for a small fee), you’ll be able to recruit your own disciples (read: minions) and earn more mo… spread the gosp… eh… I mean, you will be able to spread this wonderful new learning method to other students for mutual benefit and prosperity of mankind!

April Fool’s Day: This article was published on April Fools’ Day and even if I wish that the method I write about here would work for real, it’s actually nonsense. However, it’s still an interesting thought-experiment and most of the content is real. Lucid dreaming is real, quite easy to learn (at least it was for me) and is truly fascinating. The only part that is bogus in this article is the experiment with learning Japanese.

Why doesn’t the method work, though? I haven’t actually tried it, but there would be several problems:

- It takes too much time to learn how to control dreams in the first place

- You would learn more if you just spent the time studying the language instead

- Memories of dreams fade quite fast, even though practice helps a lot

- You can only practice what you already know, so it would be a very limited tool indeed

- There are more interesting things to do in dreams than learn languages

Still, an interesting thought experiment. If I ever decide to spend more time with lucid dreaming, I will explore language learning in dreams more. I don’t think it will be very useful, but it might still be interesting. Until then, the whole enterprise of learning languages while dreaming remains just that, a dream.

12 comments

Sign me up!

me too.

Great ideas here Olle! I have practiced (and still do occasionally) lucid dreaming.

When I was practicing the most conscientiously in my twenties, I used a lucid dream to practice and master the technique of “eskimo roll” in a kayak.. something that had been eluding me, despite having all the pieces in place. Going to read this article again and think in depth how I could put it into practice for my Chinese acquisition.

Lol, nice try Olle.

Oh so cool. I’ve often had dreams where I speak Chinese and French at the same time, though I’ve never tried doing it on purpose. Such a good idea since I lucid dream all the time 🙂

I see that you’re someone who keeps to traditions!

Best fool this year, nice job Olle.

Personally I really enjoy speaking Chinese in my dreams, and find that while dreaming I am often able to say complicated long sentences and have deep philosophical conversation far beyond my Day time Chinese skills. It has been bothering me that I have been unable to retain my dream improvements once I wake up. However lately I have found a similarly effective technique that can greatly improve your daytime Chinese. Simply drink 2-3 Qingdao and you are good to have long conversations in Chinese. This method has the added advantage of being easy to learn compared to lucid dreaming. Like the dream system the Qingdao system only gives a temporary boost, and maintaining fluency might cost you upwards of 10 RMB per day.

I will experiment more with this Qingdao method of learning Chinese and report back with my pseudo results. Should it work well I too plan to start a club where practitioners can meet and have long fluid conversations with each other.

Thank goodness. I was about half way into this section “Lucid dreams of foreign language mastery” then decided you lost the plot.

So glad you didn’t 🙂

Hilarious Olle!

After 19 years in Taiwan my dreams are still in English and in the USA. I guess I am just a slow learner.

I suspect this is the ‘Berliz problem’. Everyone goes to the bookstore and sees a book that says learn XYZ language in 30 days and think that is all there is to it.

The truth is I have learned more English in the past 19 years of teaching it in Taiwan than I learned in the previous 43 years. Language learning is lifelong, and it does make one more intelligent. Unless one grows up in a multilingual family, it is rare to every master the 2nd language as well as one’s first. BUT, learning a 2nd language is endlessly rewarding.

Expectations of perfection are a hazard to the naive. Progress, not perfection. One can always learn a bit more and enjoy doing so.

Olle,

A pleasure to run across your fine site: I like your attitude, and damn but it’s nice to run across your competence.

There is, however, one thing seriously missing from your good April 1 post on 24-hour learning. Your article is of course quite correct as far as it goes, but thee is even more good news in language learning: Quantum Chinese.

Even any single language is ambiguous to begin with, and hence a natural field for the application of the technologies of quantum uncertainty. When one is working in two languages at once, e.g. Chinese and English or any other, the advances possible through the application of quantumification become obvious.

Full details available at https://www.Heisenbergfnord.com/dev/null.esp.

Enjoy!

-dlj.