This article is a rant based on more than a decade of observing how Chinese characters are taught in classrooms around the world. What I portray here is meant to be tongue-in-cheek, poking fun at bad teaching.

This article is a rant based on more than a decade of observing how Chinese characters are taught in classrooms around the world. What I portray here is meant to be tongue-in-cheek, poking fun at bad teaching.

However, my goal is not to attack teachers; most do their best and simply don’t have the education, time or resources to get everything right. If you are a teacher, you can read this article as a guide for what to do (just reverse the wording for each advice). If you’re a beginner learning characters yourself, you should probably read this article instead: How to learn Chinese characters as a beginner.

At the end of this article, there is a poll where you can share what you have experienced yourself!

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to this article:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many more!

Beginners often regard Chinese characters with a mixture of respect, fascination and dread. If you want to make them really scared and minimise the risk of them learning the language, and, at the same time, maximise the amount of frustration and angst students feel, you’ve come to the right place!

Hacking Chinese presents…

How to not teach Chinese characters to beginners: A 12-step approach

Here I present twelve steps to terrible teaching, including links to more information whenever relevant. It’s rare to see teachers who are able to follow all the steps here, but nothing here is made up.

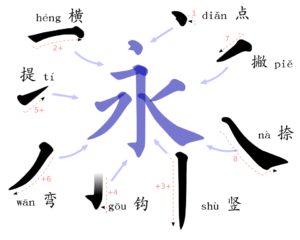

Teach the names of the strokes, preferably in Chinese – Language learning is all about theoretical, abstract knowledge, so the most important thing is for students to know what things are called, especially the various strokes that all characters are composed of. Don’t forget to include combinations of strokes, including the rare ones. It dosen’t really matter if most native speakers don’t know the names of these, your students definitely should! It’s important to learn all the stroke names in Chinese, because there are no other words with a higher priority for beginners to learn. I wrote more about learning stroke names here: Should you learn the names of the strokes in Chinese characters?

Teach the names of the strokes, preferably in Chinese – Language learning is all about theoretical, abstract knowledge, so the most important thing is for students to know what things are called, especially the various strokes that all characters are composed of. Don’t forget to include combinations of strokes, including the rare ones. It dosen’t really matter if most native speakers don’t know the names of these, your students definitely should! It’s important to learn all the stroke names in Chinese, because there are no other words with a higher priority for beginners to learn. I wrote more about learning stroke names here: Should you learn the names of the strokes in Chinese characters? Test students on their theoretical knowledge, not their practical skills – This is related to the above advice, and means that you also need to test the students’ knowledge of the theoretical, abstract concepts. For example, make sure to include the stroke names in Chinese on the test. It doesn’t matter if the students know what the characters mean or how they are used, what matters is that they can name all the strokes. Avoid practical communication and real-world applications whenever possible.

Test students on their theoretical knowledge, not their practical skills – This is related to the above advice, and means that you also need to test the students’ knowledge of the theoretical, abstract concepts. For example, make sure to include the stroke names in Chinese on the test. It doesn’t matter if the students know what the characters mean or how they are used, what matters is that they can name all the strokes. Avoid practical communication and real-world applications whenever possible. Teach how to categorise characters according to the practical and useful 六书 (六書) – When you talk about character formation, the best starting point is 六书 (六書), “Six Writings”, created roughly two thousand years ago. It’s particularly important that you expound on the two categories 假借, “rebus characters”, and 转注 (轉注) “derivative cognates”, since students will find these very hard to understand when they know nothing about Chinese characters. Avoid mentioning functional components and other concepts that could make Chinese characters make more sense.

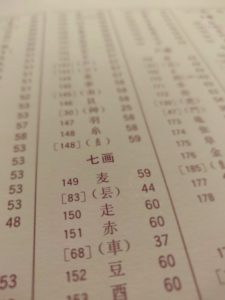

Teach how to categorise characters according to the practical and useful 六书 (六書) – When you talk about character formation, the best starting point is 六书 (六書), “Six Writings”, created roughly two thousand years ago. It’s particularly important that you expound on the two categories 假借, “rebus characters”, and 转注 (轉注) “derivative cognates”, since students will find these very hard to understand when they know nothing about Chinese characters. Avoid mentioning functional components and other concepts that could make Chinese characters make more sense. Focus on radicals from the very start – First, if you want to make learning really confusing, mix up the words “radical” (being the part of a Chinese character used to sort it in a dictionary) and “component” (being any building block of a Chinese character). The radicals might be bit arbitrary and used only in paper dictionaries, but since one of the most important skills of a student in this modern day and age of computers and smart phones is to look up characters in traditional, printed dictionaries, it’s essential that they can identify what the radical is in each character they learn from day one, including less obvious cases. As I said before, don’t mention functional components and invest all energy into the all-important radicals.

Focus on radicals from the very start – First, if you want to make learning really confusing, mix up the words “radical” (being the part of a Chinese character used to sort it in a dictionary) and “component” (being any building block of a Chinese character). The radicals might be bit arbitrary and used only in paper dictionaries, but since one of the most important skills of a student in this modern day and age of computers and smart phones is to look up characters in traditional, printed dictionaries, it’s essential that they can identify what the radical is in each character they learn from day one, including less obvious cases. As I said before, don’t mention functional components and invest all energy into the all-important radicals. Tell the students that Chinese characters are pictures – This will make characters look easier temporarily, while making sure they don’t really learn how Chinese characters work. If you can, use picture that aren’t related to either the actual components or true origin of the character. For maximum effect, cherry-pick your examples when showing how Chinese characters are pictures, and make up stuff if you have to! Again, avoid talking about functional components, especially phonetic components, since without these, it might take them months or even years before they figure out how a vast majority of characters work! This also makes sure to keep them on level 1 when it comes to understanding Chinese characters.

Tell the students that Chinese characters are pictures – This will make characters look easier temporarily, while making sure they don’t really learn how Chinese characters work. If you can, use picture that aren’t related to either the actual components or true origin of the character. For maximum effect, cherry-pick your examples when showing how Chinese characters are pictures, and make up stuff if you have to! Again, avoid talking about functional components, especially phonetic components, since without these, it might take them months or even years before they figure out how a vast majority of characters work! This also makes sure to keep them on level 1 when it comes to understanding Chinese characters. Only tell them what to learn, not how to learn – The students need to spend a lot of time learning characters in the beginning, so just dish out as much homework as you can, but don’t say anything about how to learn. Just give them a chapter reference in the textbook and say that you will test them on everything from how the characters are categorised to the names of the individual strokes. Avoid talking about how to learn Chinese characters as a beginner.

Only tell them what to learn, not how to learn – The students need to spend a lot of time learning characters in the beginning, so just dish out as much homework as you can, but don’t say anything about how to learn. Just give them a chapter reference in the textbook and say that you will test them on everything from how the characters are categorised to the names of the individual strokes. Avoid talking about how to learn Chinese characters as a beginner. Ask students to write characters 100 times to store them in long-term memory – If you do tell them anything about how to learn, tell them that they should write the characters over and over until they remember them. Ignore all the science that says that this type of repetition is very ineffective for long-term retention. Also tell the students to look at the model character while writing, making sure that they process it as shallowly as possible.

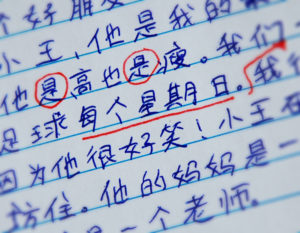

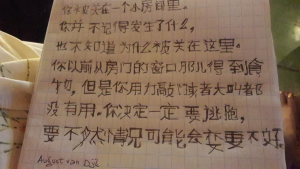

Ask students to write characters 100 times to store them in long-term memory – If you do tell them anything about how to learn, tell them that they should write the characters over and over until they remember them. Ignore all the science that says that this type of repetition is very ineffective for long-term retention. Also tell the students to look at the model character while writing, making sure that they process it as shallowly as possible. When correcting students’ handwriting, nitpick as much as possible – The goal should be to write clean, good-looking characters from day one. The standard should be that of a native speaker with a few years of schooling. Comment not only on strokes that are a bit off, also take things like balance, poise and harmony into account. Beginners have a hard time with these concepts, so you might have to focus on writing 点 (點) “dots” for a month or so before they get to anything else. This is more important than any functional goal, and it’s certainly worthwhile to take time from things like conversations and reading to spend on improving penmanship. If you hand back homework, red ink should cover at least 30% of the sheet.

When correcting students’ handwriting, nitpick as much as possible – The goal should be to write clean, good-looking characters from day one. The standard should be that of a native speaker with a few years of schooling. Comment not only on strokes that are a bit off, also take things like balance, poise and harmony into account. Beginners have a hard time with these concepts, so you might have to focus on writing 点 (點) “dots” for a month or so before they get to anything else. This is more important than any functional goal, and it’s certainly worthwhile to take time from things like conversations and reading to spend on improving penmanship. If you hand back homework, red ink should cover at least 30% of the sheet. Don’t set realistic expectations for character learning – Here you have two options, both widely used and with a long track record. First, you can claim that learning Chinese characters is really easy (see above about cherry-picking picture). Maybe you can claim that you can read newspaper headlines with only 200 characters (feel free to make up your own numbers if you wish). Second, you can claim the opposite, that learning Chinese characters is impossible for foreigners. Stress that there are 10,000 characters (or maybe 100,000 if you want to really scare them) and that it takes a lifetime to learn, even for native Chinese! Whatever you do, don’t tell the students that learning Chinese characters certainly is a challenge, but that it can be done in a reasonable amount of time.

Don’t set realistic expectations for character learning – Here you have two options, both widely used and with a long track record. First, you can claim that learning Chinese characters is really easy (see above about cherry-picking picture). Maybe you can claim that you can read newspaper headlines with only 200 characters (feel free to make up your own numbers if you wish). Second, you can claim the opposite, that learning Chinese characters is impossible for foreigners. Stress that there are 10,000 characters (or maybe 100,000 if you want to really scare them) and that it takes a lifetime to learn, even for native Chinese! Whatever you do, don’t tell the students that learning Chinese characters certainly is a challenge, but that it can be done in a reasonable amount of time. Require students to learn to write every single spoken word they encounter – This make sure that progress is really slow, and that most of the class can be spent on writing characters. After all, knowing what a word means in a conversation or being able to say it doesn’t matter if they don’t know how to write the characters; the true essence of the Chinese language. Delaying character learning is a sin.

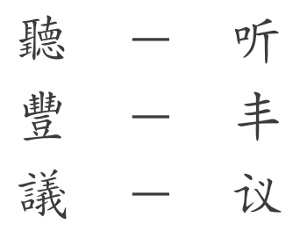

Require students to learn to write every single spoken word they encounter – This make sure that progress is really slow, and that most of the class can be spent on writing characters. After all, knowing what a word means in a conversation or being able to say it doesn’t matter if they don’t know how to write the characters; the true essence of the Chinese language. Delaying character learning is a sin. Inform students that simplified and traditional Chinese are very different – Actually, almost like two different languages. Ignore the fact that most characters are identical (all in the top ten, for example). If you focus on really exaggerated cases like 听 (聽), 丰 (豐) and 议 (議), you can make it look like the two sets are mutually unintelligible. While you’re at it, claim that simplified characters are unambiguously simpler to learn, rather than just simpler to write by hand. Don’t mention that learning the other set is in fact very easy once they’ve learnt the first.

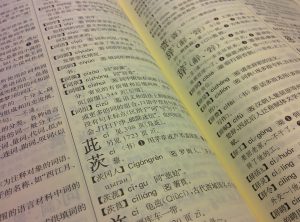

Inform students that simplified and traditional Chinese are very different – Actually, almost like two different languages. Ignore the fact that most characters are identical (all in the top ten, for example). If you focus on really exaggerated cases like 听 (聽), 丰 (豐) and 议 (議), you can make it look like the two sets are mutually unintelligible. While you’re at it, claim that simplified characters are unambiguously simpler to learn, rather than just simpler to write by hand. Don’t mention that learning the other set is in fact very easy once they’ve learnt the first. Recommend only obsolete digital tools and printed dictionaries – Paper dictionaries have been around for centuries, and if they were good enough for generations of Chinese, they’re good enough for foreigners. When it comes to software, nothing notable has happened in the past twenty years or so. In addition, be very careful with anything developed by non-native speakers, as they don’t really understand what they are doing. Definitely avoid recommending tools like Skritter, Pleco or Outlier Linguistics character dictionary. Be extra cautious with over-enthusiastic foreigners with heretical views on how to (not) teach Chinese characters to beginners!

Recommend only obsolete digital tools and printed dictionaries – Paper dictionaries have been around for centuries, and if they were good enough for generations of Chinese, they’re good enough for foreigners. When it comes to software, nothing notable has happened in the past twenty years or so. In addition, be very careful with anything developed by non-native speakers, as they don’t really understand what they are doing. Definitely avoid recommending tools like Skritter, Pleco or Outlier Linguistics character dictionary. Be extra cautious with over-enthusiastic foreigners with heretical views on how to (not) teach Chinese characters to beginners!

Follow all this advice and your students are guaranteed to feel frustration and angst. They will feel that learning Chinese characters is almost impossible, and even if it were the characters that lured them in in the first place, it will be the characters that make them quit…

…or you can do the opposite of everything I’ve said in the article and teach characters in a sensible way that makes learning both fascinating and useful. All links mentioned in the article lead to other articles with advice about how to actually learn and teach characters, and if you invert the language for each piece of advice above, you will have a reasonable list of things you should do when teaching beginners. For students reading this article, I have created a poll where you can share which of the above you have seen yourself. Am I missing something particularly terrible? Leave a comment below!

Have you seen something terrible that isn’t covered in the article? Leave a comment below!

17 comments

I should point out that I’m a Chinese teacher myself, and while I don’t think I have ever adhered to any of the “advice” offered in this article, I do recognise that a lack of time and resources can turn even a very good teacher into a mediocre one. In addition to this, many people who teach Chinese don’t have a relevant educational background, which makes them much more likely to rely on how they themselves learnt characters as kids, which is where much of the “advice” in this article comes from, I think.

Anyway, like I said in the article, the goal is not to trash-talk the teaching profession, but rather to provide advice for what to do and what to avoid. I chose to vary the way I do this for stylistic reasons, inverting good advice into bad advice that you should of course not follow. The content is the same, though: by inverting the language and doing everything the article says you should avoid, and avoiding anything it tells you to do, you have a 12-step approach to how I think characters should actually be taught to beginners. Enjoy!

After 20 years of casual study, most of it self-learning, I wish I’d learned the radicals at the start. They often give the “feel” of the character I’m looking at, rather than looking like a bunch of lines thrown together.

Just a friendly reminder: I think you mean components here, not radicals. The radical is one (and only one) part of each character that is used to sort it in dictionaries. There is really no reason to learn what the radical for each character is, although you probably do want to learn semantic and phonetic components. Often (but not always), the radical is often a semantic component, and this overlap is what causes the confusing in terminology!

I’m going to go one step farther: teaching characters just isn’t necessary in the first place.

We’ve had great (and data-supported) success since 2011 going straight to character texts, without any Pinyin support or pre-teaching of characters, radicals, phonetics, or anything else. Just lots of reading of acquired oral language (but not of stories or conversations they are previously familiar with; it’s all original content to them.) Our first-year students self-correct reading errors while reading, they retain meaning through to the end of long, complex sentences including multi-clause sentences, and they write (compose, I mean: I don’t care about handwriting-from-memory) very accurately as well.

I’d be happy to share with you how that’s done. It sounds totally counter-intuitive and no one believes it’s possible until they see it with actual beginners.

I’m not completely unfamiliar with the approach after reading some of your writing, but mostly through Diane Neubauer. I haven’t tried it myself, though, and it does seem to be something that needs to be tried to be truly understood. That being said, getting to know the method better would be interesting, not just for me, but for others who might have never heard about it. Would you be interested in writing a guest post about it? Feel free to contact me at editor@hackingchinese.com! Writing something here might be a good way to convince both me and reach more people at the same time. 🙂

I am curious what textbooks you recommend for teaching characters. Many of the things you mention in the article are in textbooks, and often teachers teach from the book.

‘Chinese characters made easy for everyone” is a good textbook! I have used it since the very beginning.

Still later, I looked for mobile and web apps to learn characters in my cell phone. I have found and tested many tools. However, there is one app that I am still using now. Hack Chinese has no advanced functionality, but it perfectly suits for learning and revising characters.

Sorry, I don’t think I can recommend any textbooks. Those that I use don’t do a very good job here, some don’t explain anything and leave it up to the teacher, which is fine by me, but like you said, can be a problem if the teacher relies heavily on the book. I’m working on a character course for Skritter that will contain all the essential stuff, kind of a distilled version of what I would normally teach beginners. If you do find good textbooks, though, please leave a comment so I can check it out. 🙂

Good article. I can add another one that’s really common, even at the higher levels of Chinese teaching (HSK5-6).

Many teachers and learning materials set exercises where the objective is to find and correct grammatical *mistakes*. On its face this might seem useful; knowing the correct grammar is important after all.

But then I noticed my teachers often make grammar mistakes when speaking to me in English, but I just hadn’t noticed before, because the focus is always in trying to understand and be understood. Looking for errors is not a thing we do when communicating.

Teaching grammar, and practicing constructing sentences, is absolutely useful, sure. But “find the mistake” is not, unless we’re trying to train students to be proofreaders.

Oh, and how can I forget “repeat after me”? Genuinely I have been in a HSK5 class with a teacher that mostly read out text herself, with students repeating what she said, line by line.

Absolutely useless.

I think this depends on how it’s done and for what purpose, but I agree it seems odd in a HSK 5 class. Saying things together in chorus is actually quite good for practising pronunciation and prosody. If you’re interested, look up Olle Kjellin’s work on chorus repetition for prosody, mainly for teaching Swedish as a second language, but works well for any language.

Interesting observation! I think there are (at least) two things involved here.

First, it’s a discussion about function and form. Traditional teachers (maybe particularly in Chinese) tend to be very form oriented, caring more about if a stroke is wrong than if the sentence is legible and makes sense. A more progressive approach is of course to regard language as functional, and if a student is able to use language to achieve a certain communicative goal, that’s the only thing that matters. This approach has some problems if taken too far, though. It might be true that one isolated stroke mistake will note make a sentence illegible (it won’t, of course), but many small mistakes can add up and make something truly incomprehensible.

Thus, we can say that “one spelling mistake is not very significant”, but we can’t say “spelling is not important”. Similarly, we can say “a single tone error is not a problem” but not “tone are not important. It’s also the case that mistakes from various domains add up, making a students Chinese less and less easy to understand.

Now over to the second part. Provided that the teacher has a reasonable approach to minor mistakes and communicative goals in general, “find the mistake” can be a valid form of assessment, I think. It can be convenient sometimes, too, because checking handwriting can be very, very time-consuming for the teacher, so rather than ask you “do you know how to write X” I can ask you “can you find the mistake in this sentence”, where I have included an incorrect version of X.

This also applies to grammar, which is what you’re talking about. If the goal is to assess someone’s grasp of the language, being able to spot which sentences a majority of native speakers would deem wrong is fine, I think. What bothers me, and what is maybe what you’re describing too, is when the “incorrect” cases presented by the teacher are actually fine for most native speakers, but not according to some artificial, formal grammar. A bit like deducting points for starting sentences with conjunction in English. Some of the more advanced proficiency tests also do this.

My comment is late Olle. When I was studying in China some of teachers liked 听写. I thought that it was a waste of time and just a way for the teacher to use up 25 minutes of class time. Even when I was called up to the whiteboard and got all the characters right I don’t think that my retention lasted more than a few days for some of the characters.

Good point! I think the process of writing down what you hear in and of itself is not necessarily a problem, but I do agree that it is a problem in many classroom, precisely for the reason you mention. This can very easily be done on your own if you think you need the practice and there’s really no good reason to use up so much time in class to do to 听写. Ideally, time with a teacher should be spent on things that can’t be done without the teacher, or are much harder to do without the teacher. I think the reason 听写 is so widespread is that it’s used as a check to see if students are doing their homework or not, but I see little reason to focus so much on handwriting in favour of all other things that could be emphasised.

The way I was taught originally involved using only kindergarten/early grade textbooks for beginner levels, the equivalent of “See Spot run” books in English, where the focus was on words like mother, father, ball and dogs and such, rather than on words useful to an adult. Character learning was rote.

It wasn’t completely without value, but inappropriate over all.

The other use of textbooks at higher levels was story after story either centring around explanations of the origins of traditional idioms, or else long historical tales. The vocabulary here was often useless to modern living.

If a conversation outside of the classroom ever did stray into idiom/historical territory, it was a rare opportunity to impress, I guess.

Basically, how to learn characters simply wasn’t taught, beyond compiling flash cards and repetitive copying.

I had to learn the component system on my own, in a second, independent go at mastering Chinese.

Very grateful for Skritter.

I teach Chinese and agree with you on most of the points (though I view “radicals” as “meaningful components” or “semantic components” and students seem fine with it). I wanted to “nitpick” one of the images you used to illustrate your points in the article. I think “是” is circled in red in the image for #8 is not because the character lacks precision but simply because it’s a grammatical error. It should be 他“很”高也“很”瘦。

Ah, yes, that’s true! I actually wrote that myself a while back for a different article and used it here for convenience. I tried simulating beginner handwriting by using my non-dominant hand and deliberately inserted some errors in the text, not all of which are related to handwriting! Well-spotted! 🙂