One of the problems with Chinese reading and listening practice is that it’s often too passive. The most motivated and disciplined students can force themselves to read and listen anyway, but most students won’t get the amount of listening and reading practice that they need.

One of the problems with Chinese reading and listening practice is that it’s often too passive. The most motivated and disciplined students can force themselves to read and listen anyway, but most students won’t get the amount of listening and reading practice that they need.

If listening and reading practice were more fun and engaging, students would be more willing to spend more time studying, and would as a result learn more.

I have written a Chinese version of this article, which is available in both simplified and traditional Chinese.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

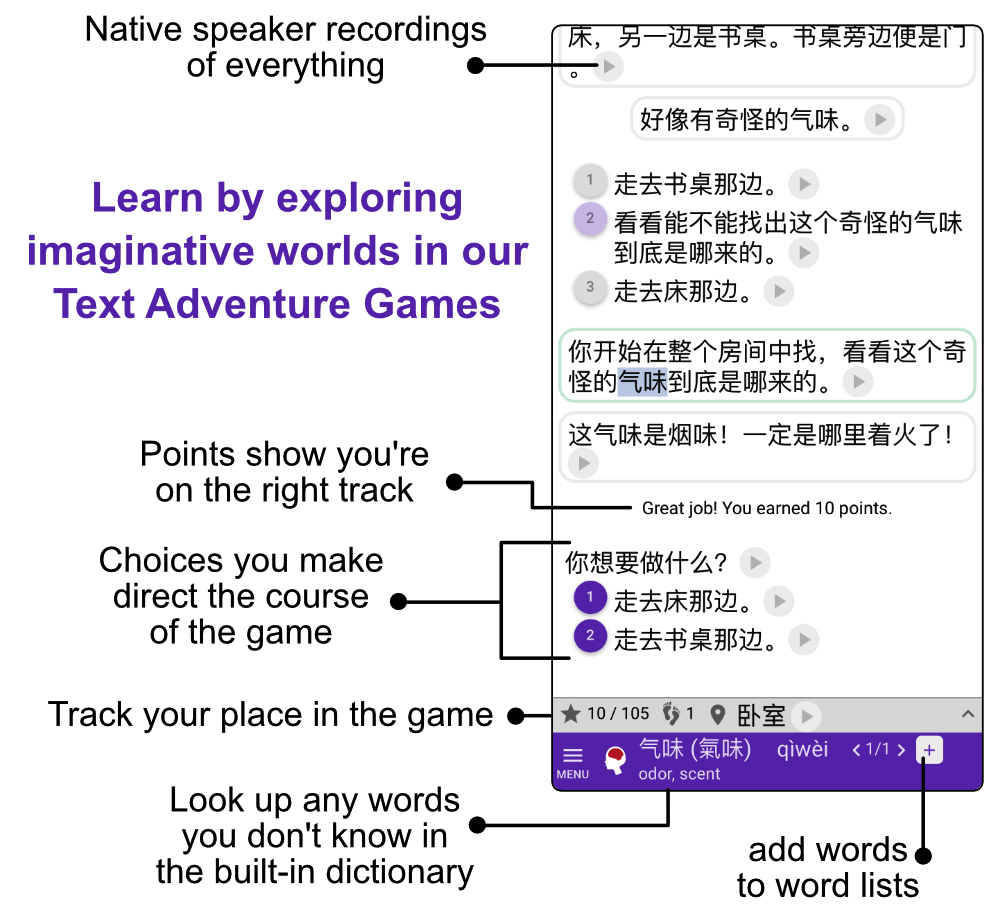

One solution to this problem is interactive text games. Instead of just being a recipient, the students are active participants who make choices that change the development and outcome of the story. Only by reading and understanding the Chinese in the game can students navigate the story to a successful conclusion. Since there is more than one ending, students are encouraged to replay the game and explore alternative paths, leading to natural repetition of vocabulary and grammar. Furthermore, understanding the text in the game is the only way of avoiding making bad decisions.

The goal of these text adventure games is to help students improve their listening and reading ability. In this article, I will mostly focus on improving reading ability using these games, but it’s equally possible to use a similar method and focus on listening ability instead.

I originally wrote this article in Chinese, so this is a loose translation to English. If you want to read or listen to the Chinese version (simplified or traditional characters), please click here. I would appreciate it very much if you would share this article with Chinese teachers you know to help me spread the word!

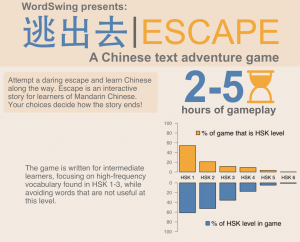

This article discusses the text adventure game Escape! If you want to play the game, you can do so here for free, without even needing to register an account. Apart from Escape! there are many other games of varying difficulty and theme to make sure everybody can find something they like. I suggest that teachers try out Escape! first, but then browse through the other games to see which might be most suitable for the students. I have written more about the other games here.

Playing text games with a Chinese teacher

In previous articles, I have discussed learning and teaching Chinese through games in general, as well as these text adventure games in particular. In this article, however, I will focus on playing adventure text games with a teacher. This means that this article is written for teachers, but also for students who might want to play text games with their teachers.

Even though I came up with the idea for these text games more than six years ago, I only tried them out in a classroom setting recently. I was sure they would work well, but was actually surprised at how well they worked. In this post, I will share a discussion of how to make the most out of playing Escape! with your students (or with your teacher if you’re a student).

Introduction and requirements

Escape! is meant for intermediate students. As a teacher, you should be able to grasp the difficulty just by playing the game for ten minutes or so, and by glancing at the graphic above. I estimate that the lower bound should be students who can handle HSK 2 content, but HSK 3 is probably better. Students at more advanced levels will enjoy the game too, but playing it will be much faster, which is not really a problem.

Here’s an overview of what I recommend:

- Use a projector to show the game interface on a big screen, or if you do this online, just share the screen

- Explain the premise of the story in English (basically the blurb, i.e. you’re wrongfully locked up in a cell and try to escape)

- Explain how the game works briefly (in English is okay)

- When the game starts, the interface will show text describing the situation, actions and dialogue

- Based on this information, students need to decide what to do next

- Once a decision has been made, it can’t be unmade; there’s no undo button

- Choices in the game are presented in random order

- There are checkpoints, so if you fail, you can start again from one of these

- There are points in the game that represent progress, but you don’t need to get all the points to finish the game

- Students play together as a group and need to discuss what to do before making a decision. If they can’t come to a unanimous decision, let them vote for different options.

- The teacher can help students with language-related problems and guide them through the Chinese, but shouldn’t meddle too much in their discussions or in the decision-making process

- Go through the first paragraphs in the game as if they were any other unfamiliar text. Because they introduces so many new things at once (they introduce the setting and the story, after all), they’re considerably harder than most other passages in the game. Take your time and make sure everybody’s on board before moving on. Draw images or use props if you want.

Completing the whole game using some variation of the approach presented in this article ought to take anything from a few hours up to ten hours, depending on the students’ level, age and how much they dwell on each scene. If they discuss each choice carefully, need lots of guidance and frequent use of the built-in dictionary, then finishing the game will take a very long time.

If time in the classroom is not enough, you can tell the students to finish the game on their own as homework. If you do, make sure that they register on WordSwing; otherwise they can’t use checkpoints and will need to start from scratch every time.

Below, I present the approach I used, which is inspired by Diane Neubauer, who wrote about her experience using Escape! in her Chinese class. Her post also includes a 15-minute video of her class, so check it out if you want a direct experience of what playing the game in a classroom can be like.

Understanding in-game text

Playing Escape! can be broken down into two steps:

- Reading and/or listening to displayed information

- Making choices based on said information

These two steps are then repeated, as each choice leads to more information that then leads to even more choices. The game ends either when really bad choices are made or when the students successfully complete the game.

When using the games to teach a group of students, the reading and listening part can be treated as any comprehension-based activity, and your favourite approach can be used. I think the best approach is to play the game together, where the students make choices collectively.

I suggest that you play the game in a web browser, zooming in enough to make the characters big and friendly, then displaying this on a projector so everyone can see clearly. Online, this is of course even easier. The teacher can then use the whiteboard to write new vocabulary and draw pictures or a map (or outsource these tasks to students).

Here are some options:

- Play audio first – Most students will find this very difficult, but it can be an excellent way of practising listening ability. Listen a few times and ask students to share what they were able to pick up, reconstructing the message together. Let them listen and read the text only after you’ve done this. When they can’t get further on their own, help them out with any gaps or answer questions. Listening first is important because while there is a lack of good reading materials, there’s an even bigger lack of good listening materials!

- Play audio together with the text – This will probably be the default approach for most situations. Having the text on screen is a great help for people who struggle with listening, and having the audio is of equal help to those who struggle with reading. The game underlines what words are currently being read, so it’s easy to follow along and make connections between the two. You can then do the same reconstruction exercises as mentioned above.

- Let students summarise or explain the passage – As a teacher, you have of course played the game in advance, so you know what is important and what isn’t. Let the students summarise in their own words what information is contained in the passage and what it implies. Let them help each other, and help them out if need be!

- Maintain a vocabulary list on the board – Escape! contains some words that the students might not be familiar with. It could be words important for playing the game like this, like 往… 走, or game-specific vocabulary such as 窗台 or 警卫. For a list of words like this, see the end of this post. Be prepared to teach these. Write them on the side of the board so that you and the students can easily refer to them throughout the lesson.

- Draw a simple map – By design, the game does not come with a map. The idea is of course that the students should be able to get the information they need from the text and that including a map is therefore, in a sense, cheating. However, to make sure that your students follow along, drawing a map as you play can be very helpful. It shows where you have been, what options might be available that they haven’t tried yet and so on. A map is also great for keeping track of relative directions (left, right and so on), which can be confusing otherwise. To engage students, ask them to draw the map. Here are some examples of student maps from various games.

- Draw pictures of objects and act out situations – The game contains no pictures for the same reason it doesn’t have a map, but again, drawing can help students understand what’s going on. If explaining in Chinese doesn’t work, drawing can make a situation clear without resorting to English. Props and acting have the same effect.

Making choices as a group

The comprehension part of playing Escape! is not magical by any means; like I said, it’s more or less like any reading or listening activity. After the students have understood the information presented to them, the real fun begins!

Since you’re playing with your students as a group, they need to make a collective decision about how to proceed. This is where communicative language learning takes place. In a small group, everybody can discuss together and present their thoughts about how to proceed. In a bigger group, you could consider dividing the students into smaller groups to discuss particularly crucial decisions in the game before reconvening. Prompt them not only to say which choice they prefer, but also why they think that’s the best option.

Here’s what it might sound like:

老师:你们觉得我们要选哪一个呢?

学生甲:不要第三个!

老师:第三个是什么意思?

学生甲:跳下去。

老师:跳下去为什么不好?可能这样可以逃出去!

学生乙:因为我们在很高的地方,不能跳下去。

老师:你怎么知道我们在很高的地方?

学生乙:我们在一个很高的房子上,跳下去很危险!

老师:好。那么你们觉得我们应该选哪一个呢?

学生乙:我觉得要选第二个。

老师:其他人呢,你们觉得我们应该选哪一个?

学生丙:我同意选第二个!

And so on.

Not all choices are interesting in the game, but many are. For example, there are many ways to approach the other prisoner in the cell next the one you start in, and students might disagree about how to solve the problem. Are they going to ignore him? Convince him to come with them? Threaten him? Let them discuss the options and decide.

Your role as a teacher should only be to make sure that they understand the options; don’t meddle too much in the decision making. If necessary, have a quick show of hands to see which option is the most popular and select that one.

This kind of discussion, both between students and between teacher and student, is the most powerful part of using these games for teaching Chinese. It makes the reading and listening both before and after important and combines it with action-oriented communication. The more students are invested in the story, the more they care about convincing the others to make the choice they think is best.

Focus on form after playing the game

An important idea in task-based language teaching is that focus on form should only come after the main task has been completed. I think this approach can be effectively applied when playing text games as well. When the students play the game, you shouldn’t spend too much time correcting pronunciation errors or fixing grammar mistakes.

If you really want to focus on these things, do so that afterwards. Since the game is quite long and will take hours to finish, I don’t mean that you should wait until the whole game is finished, just that the students should be allowed to enjoy the game and use Chinese while playing it before you focus on the language itself. Once you’ve played for a desired amount of time, feel free to bring out any form-focused activities you like.

Another useful activity that works well after playing the game is to go through the word list you created while playing the game. You will find that many of the words that recurred frequently throughout the game are no longer new to the students and they might even remember them without being prompted. Others will have only appeared once or twice in a certain part of the game and can be ignored unless you think they are important for some reason.

Text games beyond the classroom

Escape! is free to play, so students can sign up for their own accounts and play on their own. However, I suggest you don’t tell them that until you’ve finished the game once, or at least until you’ve played as much of the game as you intend to play in the classroom. You can then have them play the game on their own, exploring alternative paths and endings (there are two ways to win the game, for example). Getting a higher score can also be a good goal (155 points is the maximum). This will also give them ample time to use the built-in dictionary and actually study some of the language they might have missed in class. The options in the game are presented in random order to avoid students mechanically clicking through the game, using a specific set of choices.

You can of course also follow up with extended practice of various kinds, including writing tasks related to the story in the game. I trust that most teachers do this for other classroom activities as well and adventure text games are no different in this regard.

Resources for playing Escape! in the classroom

Most of the resources needed to play Escape! are already included in the game, but the teacher can prepare certain things regarding vocabulary. Diane used props for items she knew would appear in the game (such as having a plastic fork and a metal knife in the classroom). In order to make it easier for you as a teacher (and as a student), here are some words that are significantly harder than the rest of the game that you might want to be prepared for:

| # | Simp. | Trad. | Pinyin | Definition |

| 1 | 窗户 | 窗戶 | chuānghu | window |

| 2 | 守卫 | 守衛 | shǒuwèi | to guard |

| 3 | 走道 | 走道 | zǒudào | corridor |

| 4 | 窗台 | 窗臺 | chuāngtái | window sill |

| 5 | 实验室 | 實驗室 | shíyànshì | laboratory |

| 6 | 面具 | 面具 | miànjù | mask |

| 7 | 王 | 王 | wáng | (a surname) |

| 8 | 箱子 | 箱子 | xiāngzi | box |

| 9 | 好像 | 好像 | hǎoxiàng | as if |

| 10 | 试着 | 試着 | shìzhe | (coll.) to try to |

| 11 | 大门 | 大門 | dàmén | entrance |

| 12 | 楼梯 | 樓梯 | lóutī | stair |

| 13 | 逃 | 逃 | táo | to escape |

| 14 | 柜子 | 櫃子 | guìzi | cupboard |

| 15 | 抓住 | 抓住 | zhuāzhù | to grab |

| 16 | 刀 | 刀 | dāo | knife |

| 17 | 继续 | 繼續 | jìxù | to continue |

| 18 | 并 | 並 | bìng | (emphasis for negative words) |

| 19 | 钢刀 | 鋼刀 | gāngdāo | steel knife |

| 20 | 讨论 | 討論 | tǎolùn | to discuss |

| 21 | 情况 | 情況 | qíngkuàng | circumstances |

| 22 | 墙 | 牆 | qiáng | wall |

| 23 | 逃跑 | 逃跑 | táopǎo | to flee from sth |

| 24 | 转 | 轉 | zhuǎn | to turn |

| 25 | 引起 | 引起 | yǐnqǐ | to give rise to |

| 26 | 成功 | 成功 | chénggōng | success |

| 27 | 锁 | 鎖 | suǒ | to lock up |

| 28 | 托盘 | 托盤 | tuōpán | tray |

| 29 | 伤 | 傷 | shāng | to injure |

| 30 | 受 | 受 | shòu | to receive |

| 31 | 通过 | 通過 | tōngguò | by means of |

| 32 | 敲门 | 敲門 | qiāomén | to knock on a door |

| 33 | 警报 | 警報 | jǐngbào | (fire) alarm |

| 34 | 地下室 | 地下室 | dìxiàshì | basement |

| 35 | 尽头 | 盡頭 | jìntóu | end |

| 36 | 塑料 | 塑料 | sùliào | plastics |

| 37 | 打败 | 打敗 | dǎbài | to defeat |

| 38 | 镜子 | 鏡子 | jìngzi | mirror |

| 39 | 戴 | 戴 | dài | to put on or wear (glasses, hat, gloves etc) |

| 40 | 掉 | 掉 | diào | to fall |

| 41 | 推 | 推 | tuī | to push |

| 42 | 留 | 留 | liú | to leave (a message etc) |

| 43 | 拉 | 拉 | lā | to pull |

| 44 | 出现 | 出現 | chūxiàn | to appear |

| 45 | 假装 | 假裝 | jiǎzhuāng | to feign |

| 46 | 印记 | 印記 | yìnjì | imprint |

| 47 | 逃走 | 逃走 | táozǒu | to escape |

| 48 | 脚步 | 腳步 | jiǎobù | footstep |

| 49 | 房子 | 房子 | fángzi | house |

| 50 | 扔 | 扔 | rēng | to throw |

| 51 | 响 | 響 | xiǎng | echo |

| 52 | 到底 | 到底 | dàodǐ | finally |

| 53 | 方向 | 方向 | fāngxiàng | direction |

| 54 | 发生 | 發生 | fāshēng | to happen |

| 55 | 等 | 等 | děng | class |

| 56 | 实验 | 實驗 | shíyàn | experiment |

| 57 | 反应 | 反應 | fǎnyìng | to react |

| 58 | 文件 | 文件 | wénjiàn | document |

| 59 | 合作 | 合作 | hézuò | to cooperate |

| 60 | 试图 | 試圖 | shìtú | to attempt |

| 61 | 锁眼 | 鎖眼 | suǒyǎn | keyhole |

| 62 | 刀子 | 刀子 | dāozi | knife |

| 63 | 水池 | 水池 | shuǐchí | pond |

| 64 | 货车 | 貨車 | huòchē | truck |

| 65 | 图标 | 圖標 | túbiāo | image |

| 66 | 穿着 | 穿着 | chuānzhe | wearing |

| 67 | 讲话 | 講話 | jiǎnghuà | a speech |

| 68 | 刚刚 | 剛剛 | gānggang | just recently |

| 69 | 查看 | 查看 | chákàn | to look over |

| 70 | 躺 | 躺 | tǎng | to recline |

| 71 | 家具 | 傢俱 | jiājù | furniture |

| 72 | 对面 | 對面 | duìmiàn | (sitting) opposite |

| 73 | 压 | 壓 | yā | to press |

| 74 | 脱 | 脫 | tuō | to shed |

| 75 | 停 | 停 | tíng | to stop |

| 76 | 不管 | 不管 | bùguǎn | not to be concerned |

| 77 | 收 | 收 | shōu | to receive |

| 78 | 死 | 死 | sǐ | to die |

| 79 | 另 | 另 | lìng | other |

| 80 | 自然 | 自然 | zìrán | nature |

| 81 | 任何 | 任何 | rènhé | any |

| 82 | 躲 | 躲 | duǒ | to hide |

| 83 | 吓 | 嚇 | xìa | to scare |

| 85 | 确定 | 確定 | quèdìng | definite |

| 86 | 行为 | 行爲 | xíngwéi | action; behaviour |

| 87 | 示意 | 示意 | shìyì | to hint |

| 88 | 溜 | 溜 | liū | to slip away |

| 89 | 喂 | 喂 | wéi | hello (when answering the phone) |

| 90 | 开灯 | 開燈 | kāidēng | to turn on the light |

| 91 | 撞倒 | 撞倒 | zhuàngdǎo | to knock down |

| 92 | 纹身 | 紋身 | wénshēn | tattoo |

| 93 | 房门 | 房門 | fángmén | door of a room |

| 94 | 小声 | 小聲 | xiǎoshēng | in a low voice |

| 95 | 额头 | 額頭 | étóu | forehead |

| 96 | 招手 | 招手 | zhāoshǒu | to wave |

| 97 | 救命 | 救命 | jiùmìng | to save sb’s life |

| 98 | 囚犯 | 囚犯 | qiúfàn | prisoner |

| 99 | 快要 | 快要 | kuàiyào | almost |

| 100 | 午饭 | 午飯 | wǔfàn | lunch |

| 101 | 高楼 | 高樓 | gāolóu | high building |

| 102 | 用力 | 用力 | yònglì | to exert oneself physically |

| 103 | 转身 | 轉身 | zhuǎnshēn | (of a person) to turn round |

| 104 | 车子 | 車子 | chēzi | car or other vehicle (bicycle, truck etc) |

| 105 | 远处 | 遠處 | yuǎnchù | distant place |

| 106 | 院子 | 院子 | yuànzi | courtyard |

| 107 | 出门 | 出門 | chūmén | to go out |

| 108 | 透过 | 透過 | tòuguò | to pass through |

| 109 | 窗口 | 窗口 | chuāngkǒu | window |

| 110 | 沿着 | 沿着 | yánzhe | to go along |

| 111 | 有用 | 有用 | yǒuyòng | useful |

| 112 | 不清 | 不清 | bùqīng | unclear |

| 113 | 前进 | 前進 | qiánjìn | to go forward |

| 114 | 跟着 | 跟着 | gēnzhe | to follow after |

| 115 | 白色 | 白色 | báisè | white |

| 116 | 想法 | 想法 | xiǎngfǎ | way of thinking |

| 117 | 得到 | 得到 | dédào | to get |

Good luck escaping and let me know what you think in the comments below!

4 comments

Great post, Olle. I am not teaching learners who are yet to the level of this game, but have very fond memories of playing with US high school year 4 and AP students. Thank you for making this game available free!

Something else I did with words or phrases that I felt were useful and wanted students to retain: I introduced those words in other settings in weeks that led up to playing this game together. Many words I introduced in context, as we played, but to lower the amount of new vocab they’d encounter, I felt some could productively be introduced in advance. The opening paragraph of the game, in particular, has several terms and phrasing like that.

Yes, that’s a great idea! With hindsight, the game should probably have been written in a way that reduced the amount of new words in the opening paragraph. Of course, it will contain more new vocabulary than most other passages (as do the opening paragraph of any graded reader I have looked at), but the “shock” could have been reduced somewhat. Perhaps it would even be a good idea to deal with the first paragraph separately before actually playing the game, such as by studying it as any other text prior to starting the game.

Olle,

I am a great fan of yours. You have provided tremendous help for me leanring Chinese.

However, there is a small mistake in the sentence above: “老师:好。那么你门觉得我们应该选哪一个呢?”

Best regards, Jon

Hi Jon! Thank you for pointing this out, I have now updated the article (and the Chinese version, too, which had the same error). Also glad to hear I’ve been able to contribute to your learning!