The most common question I receive about learning Chinese is how difficult the language is. Most people assume that it’s hard, but they want to know how hard it is. This question is more complex than it seems, so let’s have a closer look!

In short, learning Chinese is difficult, but not in the way people think. Learning Chinese doesn’t require talent, high intelligence, a good ear for tones or anything like that, but it does require persistence. In this article, I will discuss in what Chinese really is difficult, and more importantly, in which sense it is not.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

The question of how difficult it is to learn Chinese is bunk

Some people argue that the question of how hard it is to learn Chinese is bunk. And they have a point. If you are reading this as a student of Chinese, it’s unlikely that that what I or anyone else says about difficulty changes anything. If I were to convince you that learning Chinese is harder than you think, what would you do with that information? If I instead persuaded you that learning Chinese is in fact easier than you think, how would that affect your learning?

Not at all, probably!

For people who are considering learning Chinese, but haven’t started yet, the question of difficulty makes more sense, but only slightly. While it’s not wrong to factor in difficulty when choosing what language to learn, other considerations should weigh more heavily. What language do you want to learn? What do you want to use it for? Besides, most people assume that learning Chinese is difficult, so if your goal is to pick an easy language to learn, it’s unlikely that you’d be reading this article.

…or is it?

Still, I don’t think that discussing how difficult learning Chinese is entirely pointless. Having realistic expectations is important, and having the wrong idea of what it means to learn Chinese can have real consequences for your learning.

If someone fooled you into believing that Chinese is easy to learn because it has no tenses, no gender and no articles, and so on, a reasonable conclusion to draw when you realise it’s not so easy is that you’re not smart enough or talented enough to learn. If the language is supposed to be easy, but you find it hard, there must be something wrong with you. This is wrong; there’s nothing wrong with you.

On the other hand, if someone tells you that learning Chinese as a foreign adult is impossible, this is not constructive either. It’s also clearly wrong, as there are plenty of foreigners who have learnt Chinese to an advanced level as adults. I started learning Chinese when I was in my mid-twenties, and I know many that started learning much later than that and have still been able to attain their goals.

How difficult is Chinese for whom?

When talking about difficulty, it’s important to keep in mind that most factors determining how hard a language is to learn are not absolute, but rather relative, depending on what languages you already know. Learning Italian as a native speaker of Spanish is not easy because Italian is inherently easy, but because the languages are close and lots of vocabulary, grammar and culture overlap. Learning Italian as a native speaker of Chinese would be much harder.

Similarly, learning Chinese is difficult because there is close to zero overlap with English or any other Indo-European language you already know. To appreciate the relative difficulty, consider what it’s like learning English for native speakers of Chinese, who of course face the same zero-overlap problem that we do when learning Chinese. Mastering tenses, articles, plurals and the like in English is extremely difficult for native speakers of Chinese.

Challenges specific to learning Chinese

Then there are some things that are intrinsically difficult with the Chinese language. The best example of this is the writing system, which is much harder to learn than in any language that uses a phonetic writing system. Yes, English spelling is a beast, and Arabic letters change their shape depending on where in a word they appear, and Greek has its own alphabet, but this is nothing compared to learning several thousand Chinese characters.

If you want to read more about Chinese-specific challenges that learners face, I check out the following articles:

Why is listening in Chinese so hard?

6 challenges students face when learning to read Chinese and how to overcome them

6 challenges students face when learning to read Chinese and how to overcome them

Can you become fluent in Chinese in three months?

And if you haven’t read it already, I also suggest you check out David Moser’s Why Chinese Is So Damn Hard, even though some of those challenges have become much easier to tackle thanks to The new paperless revolution in Chinese reading (also by David Moser).

Chinese is easy to learn! Chinese is impossible to learn!

There are many claims about the difficulty of learning Chinese, from “it’s easy”, which is usually followed by a sales pitch for a product that puports to make it easy to learn, to “it’s impossible”, which is closer to what the average person thinks. As I’ve already said, none of these extremes makes much sense and both are provably false.

Claiming that Chinese is easier than people think, relatively speaking, is more defensible as an attempt to counter the notion that learning Chinese is impossible. This doesn’t need to involving trickery, because there are in fact several points on which Chinese is easier to learn than many other languages. I have in fact done so myself here: Learning Chinese is easier than you think

Is Chinese difficult to learn? Yes, but not in the way you think!

To understand the question of difficulty better, we need to look closer at what we mean when we say that something is “difficult”. There are two distinct ways in which something can be difficult, but we usually mix them up in the everyday usage.

Let me introduce vertical difficulty and horizontal difficulty:

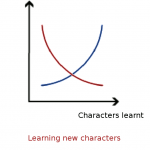

Vertical difficulty is when each step is difficult and is what most people think of when they say that something is difficult. It means that to advance, you need to improve your skill in a way which isn’t merely incremental, and success isn’t necessarily guaranteed just because you try over and over. For instance, I’ve tried bouldering a few times and even though I meet the physical requirements, if I try a difficult route, I simply won’t succeed, even if I try a dozen times. This is where vertical difficulty comes from; you need to master new skills to advance, and progress is not guaranteed. It might depend on your method, instructor, ability in other areas, luck and much more. You need to change something you’re doing, not just doing more of the same. If you fail, you fail because the next step was simply too hard.

Vertical difficulty is when each step is difficult and is what most people think of when they say that something is difficult. It means that to advance, you need to improve your skill in a way which isn’t merely incremental, and success isn’t necessarily guaranteed just because you try over and over. For instance, I’ve tried bouldering a few times and even though I meet the physical requirements, if I try a difficult route, I simply won’t succeed, even if I try a dozen times. This is where vertical difficulty comes from; you need to master new skills to advance, and progress is not guaranteed. It might depend on your method, instructor, ability in other areas, luck and much more. You need to change something you’re doing, not just doing more of the same. If you fail, you fail because the next step was simply too hard. Horizontal difficulty is when each step is easy, but it’s the total number of steps required that creates the difficulty. This requires you to do the same or similar things over and over, for a long time. It requires grit; it’s the kind of activity where success in guaranteed eventually as long as you don’t give up. An example would be to walk a thousand miles, which most people won’t fail because a certain (literal) step along the way is too hard, but because there are too many steps in total. This is where horizontal difficulty comes from. You will succeed if you persist, and doing more of the same thing will bring you closer to your goal. If you fail, it will be because there are too many steps.

Horizontal difficulty is when each step is easy, but it’s the total number of steps required that creates the difficulty. This requires you to do the same or similar things over and over, for a long time. It requires grit; it’s the kind of activity where success in guaranteed eventually as long as you don’t give up. An example would be to walk a thousand miles, which most people won’t fail because a certain (literal) step along the way is too hard, but because there are too many steps in total. This is where horizontal difficulty comes from. You will succeed if you persist, and doing more of the same thing will bring you closer to your goal. If you fail, it will be because there are too many steps.

These are two distinct types of difficulty. Naturally, there are no tasks that are perfectly vertical (not even climbing, which is literally vertical) and there are no tasks that are perfectly horizontal either (not even walking, which is literally horizontal). It’s a spectrum. Or a slope with varying steepness.

Is Chinese difficult in a vertical or horizontal sense?

Learning a language is a complex process, so we shouldn’t expect all challenges it presents to be difficult in the same way. As we shall see, what kind of difficulty a certain aspect has also depends on your level, because in general, the more familiar you are with a process, the more horizontal the difficulty becomes.

Let’s have a look at some things with vertical and horizontal difficulty that students of Chinese encounter:

Aspects of learning Chinese with vertical difficulty

Learning basic pronunciation and tones – This is a clear example of vertical difficulty. As an adult, you cannot count on learning decent pronunciation by osmosis. There’s a real risk of failure, especially if you don’t prioritise pronunciation. Simply listening and speaking might work for some, but it’s far from guaranteed to work. If you’re interested, you can check out my pronunciation course here: Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence.

Learning basic pronunciation and tones – This is a clear example of vertical difficulty. As an adult, you cannot count on learning decent pronunciation by osmosis. There’s a real risk of failure, especially if you don’t prioritise pronunciation. Simply listening and speaking might work for some, but it’s far from guaranteed to work. If you’re interested, you can check out my pronunciation course here: Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence. Understanding characters – Learning many characters is a good example of horizontal difficulty, but getting the hang of the writing system in general is more vertical. It requires concentrated effort and some guidance. This is not hard to get (check this series of articles for example), but it’s certainly a challenge for most students. Note that learning large numbers of characters is clearly a horizontally difficulty process (see below).

Understanding characters – Learning many characters is a good example of horizontal difficulty, but getting the hang of the writing system in general is more vertical. It requires concentrated effort and some guidance. This is not hard to get (check this series of articles for example), but it’s certainly a challenge for most students. Note that learning large numbers of characters is clearly a horizontally difficulty process (see below). Handwriting (beginners) – Writing by hand as a beginner is hard because you haven’t internalised the rules and conventions that underpin the writing system. Writing more helps, but there’s more to handwriting than that. To learn to write by hand properly, you can use tools such as Skritter.

Handwriting (beginners) – Writing by hand as a beginner is hard because you haven’t internalised the rules and conventions that underpin the writing system. Writing more helps, but there’s more to handwriting than that. To learn to write by hand properly, you can use tools such as Skritter.

Aspects of learning Chinese with horizontal difficulty

Learning thousands of characters – Once you’ve learnt a basic set of characters and character components (such as the 150 we teach in the Skritter Character Course), learning more characters and components is not hard in the vertical sense anymore. The problem isn’t that each character is hard to learn, but that you need to learn thousands of characters to become literate. You also run into the real challenge with learning Chinese characters, namely to keep characters a part. This is the clearest example of horizontal difficulty I can think of when it comes to learning Chinese.

Learning thousands of characters – Once you’ve learnt a basic set of characters and character components (such as the 150 we teach in the Skritter Character Course), learning more characters and components is not hard in the vertical sense anymore. The problem isn’t that each character is hard to learn, but that you need to learn thousands of characters to become literate. You also run into the real challenge with learning Chinese characters, namely to keep characters a part. This is the clearest example of horizontal difficulty I can think of when it comes to learning Chinese. Learning thousands of collocations – To sound natural in Chinese, you need to know which words tend to go with which other words, which is called “collocations” in linguistics. In Chinese, the sun is “big” when it’s sunny (太阳很大, tàiyang hěn dà), and so is “rain” when it rains (雨很大 yǔ hěn dà). There is no way to know this without having encountered these phrases, so the only way to learn it is on a case-by-case basis, and then sometimes by spotting patterns. This can be hard, though. For example, there are many characters that mean “person” in some sense, including 家 (jiā), e.g. 作家 (zuòjiā) “author”, 者 (zhě), e.g. 记者 (jìzhě) “journalist”, 生 (shēng), e.g. 学生 (xuésheng) “student”, 师 (shī), e.g. 律师 (lǜshī) “lawyer”, 人 (rén), eg. 军人 (jūnrén) “soldier”. How do you know when to use which? You don’t, unless you have encountered words these characters are contained in many, many times. Read more in this article: The building blocks of Chinese, part 6: Learning and remembering compound words.

Learning thousands of collocations – To sound natural in Chinese, you need to know which words tend to go with which other words, which is called “collocations” in linguistics. In Chinese, the sun is “big” when it’s sunny (太阳很大, tàiyang hěn dà), and so is “rain” when it rains (雨很大 yǔ hěn dà). There is no way to know this without having encountered these phrases, so the only way to learn it is on a case-by-case basis, and then sometimes by spotting patterns. This can be hard, though. For example, there are many characters that mean “person” in some sense, including 家 (jiā), e.g. 作家 (zuòjiā) “author”, 者 (zhě), e.g. 记者 (jìzhě) “journalist”, 生 (shēng), e.g. 学生 (xuésheng) “student”, 师 (shī), e.g. 律师 (lǜshī) “lawyer”, 人 (rén), eg. 军人 (jūnrén) “soldier”. How do you know when to use which? You don’t, unless you have encountered words these characters are contained in many, many times. Read more in this article: The building blocks of Chinese, part 6: Learning and remembering compound words. Improving listening ability – Despite everything I’ve written about listening ability here on Hacking Chinese, improving listening ability is still mostly a matter of practice. Sure, you can use different methods to improve faster, but the results will be more dependent on how much you listen than how you listen, provided you stick to reasonable approaches to listening, making sure that you understand what you’re listening to. There are very few shortcuts when it comes to listening ability.

Improving listening ability – Despite everything I’ve written about listening ability here on Hacking Chinese, improving listening ability is still mostly a matter of practice. Sure, you can use different methods to improve faster, but the results will be more dependent on how much you listen than how you listen, provided you stick to reasonable approaches to listening, making sure that you understand what you’re listening to. There are very few shortcuts when it comes to listening ability.

As you can see, all the examples listed for vertical difficulty are limited to the beginner stage of learning and most of the horizontal difficulty follows later. This is not necessarily true in all cases, but it is a general trend. I could also have added many more examples of horizontal difficulty, such as handwriting for non-beginners, reading ability (especially reading speed) and many more.

How you learn Chinese matters in different ways

One consequence of the above argument is that the method you use for learning Chinese has a different impact on aspects of the language with vertical and horizontal difficulty. For horizontal difficulty, the most crucial factor is how much time you spend, so finding methods that you like and are willing to invest a lot of time in are superior to those you don’t like and avoid using for that reason. Still, you also want to make sure that each hour you invest counts for as much as possible. Read more in Should you use an efficient method for learning Chinese even if you hate it?

Should you use an efficient method for learning Chinese even if you hate it?

When you encounter a challenge with vertical difficulty, the method is important because it can make it possible to succeed. This is more about effectiveness than efficiency. A good method allows you to improve, whereas a bad one doesn’t.

Let’s have a look at pronunciation as an example. You could try to learn tones by reading the Pinyin in your textbook aloud, but this would horribly ineffective, and any success you might see is despite the method, not thanks to it. If you instead focus on listening intently, mimicking and getting feedback, you stand a better chance of succeeding. This is why I created a whole pronunciation course to help students speak clearly and with confidence:

Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence

When I designed the course, I made sure to structure lessons as intuitively as possible. Just to take one concrete example, the sounds j, q and x are often taught in that order, but this puts the easiest sound last. Instead, by focusing on x first, and then learning how to use that tongue position to also nail j and q, learning this series becomes easier. And if you thoroughly understand the differences between pairs like d/t and b/p, you can rely on this knowledge to master j and q as well.

This is a good example of vertical difficulty, because trying to learn how to pronounce j and q without having mastered d, t and x is just unnecessarily hard. This also happens to be the same process as for z/c/s and zh/ch/sh, which can be helpful if taught properly.

Varying the slope: Learning more by making it easier or harder

Let’s expand the concept of difficulty as a slope of varying steepness. As a learner, you can influence the slope to make learning more horizontal or more vertical

For example, when it comes to reading, you can focus on reading extensively, which entails reading a lot of text at a relatively easy level, or you can read intensively, where you focus on more difficult texts, but read less characters in total. Both these are valuable, but since students in general already focus too much on intensive reading, I recommend extensive reading:

I have deliberately sought out difficult challenges many times on my Chinese journey, so I also think that making learning more vertical can also be helpful, something I discussed in more detail here: Is taking a Chinese course that’s too hard good for your learning?

Is taking a Chinese course that’s too hard good for your learning?

Learning Chinese is difficult in a horizontal way

Yes, learning Chinese is difficult, but more in the sense that walking a thousand miles is difficult, not in the sense that climbing is difficult. At least once you get past the beginner hump. Thus, it might seem like Chinese is hard, even impossible to learn, and that succeeding requires abilities or talents you don’t have, but it isn’t so. If you find it hard to get past the beginner hump, I have collected my best advice in my course Unlocking Chinese: The ultimate course for beginners, but if you want free advice, you can also check the beginner page here on the site.

Learning Chinese requires commitment and perseverance. Most people who fail to learn Chinese do so because there are too many steps, even if each step is easy, not because of a specific step being too hard. This should be encouraging, because it means that anyone can learn leran Chinese, you just need to keep at it!

Did you find Chinese easier or harder to learn than you expected? Leave a comment and share your experience!

Editor’s note: This article, originally published in 2014, was rewritten from scratch and massively updated in July, 2023.

18 comments

The answer, by the way, is yes.

Yes, but that would have made for a poor article. 🙂

I found your vertical/ horizontal distinction interesting, and I agree that the biggest problem with learning Chinese is the necessity of a long-term commitment, but it does seem as if you are trying your best not to say that learning Chinese is significantly harder for many Westerners than learning a language more closely related to one’s mother tongue. In all categories of language acquisition, Chinese offers substantial hurdles that do not exist for a learner of many other languages popular in the West. This starts with the absence of an alphabet, where an unfamiliar character offers only vague and unreliable pronunciation hints and ends with having to adapt to a tonal language full of homophones that must be distinguished by context. In the middle are the standard grammatical pitfalls and stumbling blocks that one always encounters when learning a foreign language. As a personal anecdote, I have spent 1/10th of the amount of time learning Dutch as I have spent learning Chinese, and already my Dutch is better than my Chinese in every aspect. I realize that it’s not good to focus too much on difficulties, but learning Chinese offers more than a handful.

I think that, on the whole I agree with what you’ve said, Olle. To add to it, I also agree with the comment above about difference from the mother tongue.

I often find myself embroiled in the ‘do you need to study/have lessons or can you just learn by talking to people’ argument and I think that, with certain language, an English speaker can do quite a lot by just practising. Take Spanish, for example. If I wanted to say ‘I am 3 years older than you’, in Spanish I can more or less use Spanish words in English order and I have a good chance of being correct, or at least perfectly comprehensible. With Chinese, it’s a very different story. That, I think, is the real difficulty with Chinese. Once one knows the sentence patterns/structures, then it’s a fairly easy language to put together (once, as you say, the learner has got over the pronunciation hurdles etc). If one never actually learns these structures properly and just makes it up from English, ones Chinese remains eye wateringly poor and one never improves. I’ve seen that happen time and time again with the ‘I don’t need to study/I haven’t time’ people and I’ve yet to meet someone who made a success of Chinese by failing to study!!

Yes, learning vocab and characters etc can be seen as ‘hard’, but it becomes easier as one becomes more familiar with the way Chinese characters and indeed words are formed, the less of a struggle it becomes. Vocab learning is a drag with many languages. I have an awful time remembering German vocab, but that is, I strongly suspect, something to do with my not putting nearly enough time in on it….!!!:)

It’s like any endeavour – you only get out what you put in.

Chinese is so darn ‘horizontal’ that a beginning learner might do well to look hard at the opportunity cost involved in the endeavor! However, on the flip side, even just reaching an elementary level can offer some excellent rewards.

I am a Chinese speaks mandarin(Chinese of normal accent). After reading your article, I come up an idea that you should teath a Chinese person such as me, to learn English rather than teaching Chinese to English native speakers. And maybe, in exchange, I can take your job to teach them Chinese. As you know, a native speaker get the vertical skills natively naturally advantageously than a foreign learner. Even an advanced of years of learning still get much closer to the origin, or they just use another way to get similar effect, but not the origin. The very reason is just because the vertical skill is too too abstract to be expressed literally for a foreign to get accurately in the learning process. After all it is mystery of nature, the vertical skill is like 任督六脉. A native baby or child breaks it through easiliy but not an advenced learner. After that, the rest is all about time consuming and blocks building as a native learns their owns to get literate.

I like the article a lot. As a native Chinese guy born in a family without talents in languages, I had a very hard time in learning English at school. Only after 6 years of overseas study in England from 1998-2004, and with continuous learning after my return, I am now much more confident than before in handling this foreign language in public. Of course, mistakes are still many. By reading the author’s words, it rings bells in my head and reminds my own hard times. To be honest, English is as scary to Chinese, as Chinese is to non-native speakers. The article explains pretty well about the potential difficulties one may encounter in learning Chinese, in an objective manner. I may speak Chinese a bit more fluent than the author, but the latter is certainly much more capable of helping Westerners to learn Chinese than I am. So, for beginners, I suggest you trust what the article says, it surely has my endorsement.

I have found Chinese to be both the hardest language I have ever learned but also one I have seemed to apprehend the fastest. Perhaps the speed is because of my obsessive immersion, more so than my previous language endeavors.

The hardest things for me have been:

1. My vocabulary expansion being slowed by having to learn characters.

2. Rearranging sentence structures in my brain.

3. Getting over my personal need to SEE new words in pinyin before I feel like I actually can hear them properly.

4. Knowing which Hanzi to learn first.

When learning Latin, my biggest hurdle was noun and verb endings, the biggest hurdle for me in Chinese is learning to read so I can consume more content and build vocabulary and grammar. I’ve never started learning a new language whilst also being illiterate before. It’s really something.

Thanks for sharing! You mention something here I didn’t mention in the article or podcast, namely that because languages are difficult in somewhat different ways, people will also have different experiences depending on preference/aptitude/attitude. I engage a lot with teachers in upper-secondary school here in Sweden, and it’s common for students to choose Chinese because they want to learn something different, sometimes even to get away from the endless grammar of German or French. Naturally, I think this also indicates that there are problems with how these languages are being taught, but it’s certainly true that student prefer different things, and that will influence how they perceive the difficulty of learning Chinese.

As for your list of hardest things, I have experienced all those myself too. I think the first one is probably the biggest in terms of impact, but the others are important too. The third one I think goes away once you’ve fully learnt Pinyin. There aren’t that many syllables and once you’re familiar with them, it’s more a matter of which sound it is than what sound it is. For tones, this persists longer, I feel, and I still sometimes double check tones with native speakers to make sure I got it right.