Chinese characters can be magically beautiful and mysterious. I still remember what it feels like to look at them and be attracted by them without understanding what they meant. Indeed, many students start learning Chinese because of the characters!

Chinese characters can be magically beautiful and mysterious. I still remember what it feels like to look at them and be attracted by them without understanding what they meant. Indeed, many students start learning Chinese because of the characters!

Chinese characters can also be frustratingly difficult and, compared with any other major language, extremely time-consuming to learn. This is particularly true for writing characters by hand, which takes many times longer than learning to read.

Considering how much time it takes to learn to write characters by hand, it’s only natural to ask if it’s worth it: Do you have to learn to write Chinese characters by hand? Or to make it a bit more interesting: Should you learn to write Chinese characters by hand?

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

That’s what this article is about. I will look at these questions from different angles, with the goal of helping you find an approach that works for you, or if you’re a teacher, an approach that works for your students. I have divided the content into six parts. If you already have basic knowledge of the Chinese writing system (i.e. you understand the problem I’m addressing here), you might want to skip the first part, which I’ve included for those new to the subject.

- Writing by hand in Chinese is a separate skill

- The practical argument: Do you need to be able to write by hand?

- The interest argument: Do you like to write by hand?

- The education argument: Are you required to be able to write by hand?

- The processing argument: Do you learn more if you write by hand?

- Conclusion: Learning Chinese without learning to write by hand?

1. Writing by hand in Chinese is a separate skill

In most other languages, having learnt basic spelling and then relying on reading and typing is enough to maintain the ability to write by hand. This is because remembering how to write the letters of an alphabet is not hard, while remembering how to write thousands of characters is hard.

For example, I have not written much by hand in English in my life, and almost nothing since graduating from university. Still, I’m sure I could write the article you’re now reading by hand if I wanted to, even though it would make my hand hurt. If the article had been in Chinese and I hadn’t practised handwriting for a decade, I would certainly not be able to write much at all by hand.

The main reason is that typing and writing by hand are cognitively very different processes in Chinese. In English, each letter is associated with a key or combination of keys on the keyboard, so each time you type a word like “accommodate”, you need to know how many times to hit c and m, and each time you type “receive”, you need to make sure to hit the e and i in the right order. Every time you type these words, you reinforce your ability to spell them. If you blindly rely on auto correct 100% of the time, this might not be enough, of course!

In Chinese, the most common way to input characters is via phonetic input, which means that you type how something is pronounced, and a program called an IME (Input Method Editor) then picks the characters it thinks you want to use based on character and word frequencies, as well as prior typing habits and sophisticated machine learning.

Modern input methods are very good at picking the right characters given context, at least if you stick to standard and common language. This means that typing in Chinese requires you to know the pronunciation of the character and sometimes the difference between characters with the same pronunciation. Clearly, typing does not reinforce the knowledge required to write by hand, which includes structure, components, stroke details, as well as the ability to keep similar characters apart.

I should mention that here are input methods that aren’t phonetic, but these are rare. Those that are built on what the characters look like and how they are structured are also very difficult to learn for partly the same reasons handwriting is difficult to learn. If you want to know more about input methods in general, I suggest you check out this article and podcast episode: Chinese input methods: A guide for second language learners

This brings us to reading, which is a comparatively passive way of processing written characters. In English, there are less than a hundred commonly used letters and symbols, so learning them once and then seeing them over and over every time you read a text is usually enough.

In case of rarer characters, this might not always work. For example, I remember as a teenager having to think a bit before writing an ampersand (&) and occasionally flipping capital Greek sigma (Σ) horizontally. Obviously, I knew what these symbols meant and could read them much earlier than I could write them. I bet it’s not uncommon to be at least a little bit unsure of how they are written by hand!

This is what writing Chinese by hand is like, except you don’t have a handful of these symbols, but thousands, and they can have everything from just a few strokes up to dozens of strokes, making the average character far more complex than an ampersand or a sigma. Reading and typing alone is clearly not enough to either acquire or maintain the ability to write most Chinese characters by hand. Recognition is always much easier than recall.

2. The practical argument: Do you need to be able to write by hand?

Now that we know what the problem is, let’s continue by looking at it from a practical point of view: Do you actually need to be able to write Chinese characters by hand? If sticking to reading and typing will save so much hassle, can you just skip handwriting?

Naturally, the answer to this question will vary from person to person because we need different things, but to establish a foundation, let’s ask an easier question: When was the last time you needed to write something in your native language by hand?

Some people, including myself, don’t write much by hand in their native language at all. These days, my handwriting is limited to:

Notes when reading printed articles

Notes when reading printed articles- Brainstorming when I want to be free of digital distractions

- Small notes written to family, neighbours and the like

- Addresses on envelopes on the off chance I need to send something by mail

- Writing on a whiteboard when teaching on campus (which I rarely do)

Your list might be shorter or longer than mine, but if we stick to things you need to do by hand, most lists can be shrunk to almost nothing. I could take notes digitally, brainstorm with a computer, print addresses and so on, it’s just that I prefer not to or that it’s more convenient to write by hand sometimes. I could probably get away with not writing on the white board either and use a projector instead.

But Olle, you live in Sweden, of course you don’t need to write Chinese by hand very often!

Yes, that’s true, but even when I lived in Taiwan (which I’ve done for four years), I rarely had to write by hand outside the confines of language schools and universities (a perspective I will return to later in this article). I occasionally encountered some of the situations mentioned above (notes, small messages, addresses, and the occasional form), but in all these situations, I could have used my phone to look up how to write the characters if need be.

I didn’t, because I had to sit long, handwritten exams in linguistics and pedagogy in grad school, so I had to know how to write by hand well, but I could have managed without, at least outside my education. If you talk with other advanced learners, including those who live in China, this experience is rather common; handwriting is almost always optional, and when you do need it, you can usually “cheat”.

So, in short, the answer to the question if you need to be able to write by hand from a practical standpoint is almost always “no”. While there could be scenarios, such as specific lines of work, where you really need to write by hand, it seems far fetched to study with the assumption that you will end up with such a job, especially since you can always learn to write by hand later.

3. The interest argument: Do you like to write by hand?

Before we continue the discussion about whether or not you should learn to write by hand, let’s acknowledge that some learners love characters, and like I said in the introduction, some even start learning Chinese because of characters. For you, learning characters is a pleasure. Maybe you like the intricate history behind each character, maybe you like calligraphy, maybe it’s something else, but you are interested in characters, just like other people might be interesting in football, bird watching or knitting.

If this description fits you, you can take most of what I say in this article with a pinch of salt; I’m not trying to convince you to stop doing something you love! However, that doesn’t mean that everything I bring up here is irrelevant, because even if you love characters, it doesn’t automatically follow that pouring all your available time into learning them is a wise strategy. There are other areas of learning that might be even more important to reach your goals!

Still, most of what I talk about here is for those who don’t love learning characters and would rather spend that time improving other areas of the language, or on football, bird watching or knitting.

Personally, I’d place myself somewhere in the middle: I don’t love characters, but I’m certainly interested in them and enjoy learning more about how they are structured and where they come from. This interest is not strong enough to make me write characters for fun, but it’s enough to make me enjoy building a character course over at Skritter and work with Chinese language standards and corrections. I have also learnt at least 6,000 characters and mostly don’t regret doing that (although maybe I do for the rarest 1,000 or so that really aren’t that useful).

This is the trailer for the course, presented by Gwilym James.

4. The education argument: Are you required to be able to write by hand?

If you ask advanced students about when they were last required to write Chinese characters by hand, most of them, including myself, will answer “in school”, including language schools, university courses and everything in between. If they answer something else, it’s usually because they have very specific jobs that require them to write Chinese by hand, but that’s exceedingly rare. I have worked with Chinese language education full time for about a decade and have never been required to write characters by hand, even if I often do so when teaching because it’s more convenient than typing, especially when teaching on campus.

While curricula vary across the world, handwriting is often a compulsory component in many educational settings. This, however, is a very weak argument for handwriting. If you don’t need to write by hand, and many advanced students say that they hardly ever do, why should it be a required part of the curriculum?

This question is much too big for this article, but the answer is probably more related to tradition than students’ needs. While there is a case for learning to write some characters by hand (more about this later), it’s certainly a bad idea to learn to write all characters by hand. This is an area where I think the curriculum for teaching Chinese in Swedish schools is spot on: Students are required to be able to read and type texts about certain topics at a certain level, but they are only required to write a smaller subset by hand.

This is also reflected in the new standard for the dominant proficiency test for Chinese learners, HSK, which comes with a separate list of characters for handwriting. This list is considerably shorter than the general vocabulary list for a given level, indicating that in many cases, reading and typing is enough. I wrote more about the new HSK 3.0 standard here:

5. The processing argument: Do you learn more if you write by hand?

As I pointed out earlier, writing a character requires you to process it more deeply than if you just read it. In general, deeper processing leads to better learning, so one argument for learning to write by hand is that you will then learn and remember more characters.

This is probably true, but it’s important to not forget to take opportunity cost into account. If your teacher gives you twenty characters to learn by next Friday, it takes much longer if you’re meant to be able to write them by hand compared to if you just need to recognise them. That’s time you could have spent reading and listening. Thus, while deeper processing is certainly better, it also takes much longer, so is it worth it?

It’s impossible to answer to answer this question, because there are so many situational factors to take into account, so instead, I’ll give you a summary of my take on the issue of handwriting characters in language classrooms. This is mainly for adult second-language learners, but it’s applicable in senior high-schools too.

I think the sequence ought to be something like this:

- Acquire a solid foundation in the spoken language

- Learn to read things you can already understand in the spoken language

- Learn the basics of how characters work and some handwriting

I’ve argued the case of delaying characters before, so I won’t elaborate here, but check out Should you learn to speak Chinese before you learn Chinese characters? if you’re interested.

Should you learn to speak Chinese before you learn Chinese characters?

People who argue that characters should be introduced from day one are usually the same people who argue that you have to learn to write characters by hand, otherwise you’re not really learning Chinese. This is, in my opinion, a bit silly, because nobody learns Chinese like that outside foreign-language classrooms. Native speakers certainly don’t; they have many years exposure to the spoken language and can use it fluently when they start learning to read and write.

Once you have a foundation in the spoken language, the question then becomes how many characters you should learn to write by hand , assuming that your goal is to understand characters to boost your reading ability further down the line. Handwriting is useful here, because recalling how to write characters from memory is an active process that requires you to really know the characters. You can’t just say “it’s that character with a tree on the left and then a shape that looks vaguely like this on the right”, you have to really know the components.

Exactly how many characters you need to learn to write before you get a good feel for the writing system is hard to tell. If you just mindlessly copy them, you can learn 10,000 characters and still have no clue how they work, but if you take the course I built with Skritter, learning the 150 or so characters that are included might be enough. If you’re not interested in the Skritter course and want a free, written alternative, I suggest this series of articles that start with The building blocks of Chinese, part 1: Chinese characters and words in a nutshell

The building blocks of Chinese, part 1: Chinese characters and words in a nutshell

Or you can check out a more advanced course from Outlier Linguistics (and the dictionary they offer; neither is free):

I’ve already mentioned HSK 3.0 above, but I want to repeat that the standard there makes a lot of sense. If you’re about to leave the beginner stage (having reached new HSK 3), knowing 300 characters by hand is not unreasonable. If you’re about to complete the intermediate phase (new HSK 6), knowing another 400 characters isn’t too much to ask. And if you’ve already reached an advanced level (new HSK 7-9), adding another 500 for a total of 1,200 seems reasonable.

Can you get away with less than this? Of course you can, but I would still suggest that learning these characters and then letting the rarer or more difficult of them go over time if you don’t need them is better than not learning them in the first place.

6. Conclusion: Learning Chinese without learning to write by hand?

If you say that you’re learning Chinese, but that you don’t know any characters, most people will say that you’re only learning half the language. And rightfully so: Learning Chinese without characters is very limiting and it’s impossible to be fully functional in a Chinese-speaking social or professional context without being able to at least read and type.

Still, for some people, ignoring characters is the right choice, because being fully functional is not part of their goal for learning the language. If you just want to be able to talk to your in-laws or chat with Chinese tourists, knowledge of characters is not required. Useful, yes, but not required, and it’s not worth the huge effort needed to learn them.

If you say that you’re learning Chinese, but that you don’t care about writing by hand specifically, fewer people will be horrified, and most of those who would be horrified are traditionally-minded teachers you can safely ignore. In addition, not being able to write everything by hand is a problem even educated native speakers can relate to. They also forget how to write characters on a regular basis.

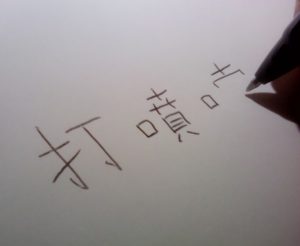

A infamous example of this is to ask native speakers if they can write dǎ pēntì de tì (打喷嚏的嚏, i.e. 嚏) by hand. Students usually can, but adults with a decade or more between now and graduation often can not. There’s even an idiom for this: 提笔忘字, literally “lift brush/pen [as if to write], forget character”. It’s not a new phenomenon either, even though it has of course become much worse with an increased reliance on the phonetic input methods mentioned earlier.

A infamous example of this is to ask native speakers if they can write dǎ pēntì de tì (打喷嚏的嚏, i.e. 嚏) by hand. Students usually can, but adults with a decade or more between now and graduation often can not. There’s even an idiom for this: 提笔忘字, literally “lift brush/pen [as if to write], forget character”. It’s not a new phenomenon either, even though it has of course become much worse with an increased reliance on the phonetic input methods mentioned earlier.

In the end, how you choose to approach Chinese characters and how much you focus on handwriting is up to you. If you’re unlucky, it might also be determined at least partly by your environment, especially if you’re enrolled in formal courses.

My goal in this article was to discuss the question from different angles to provide you with a basis to form your own opinion. And remember, if you change your mind later, you can always pick up handwriting again if you actually need it, or the reverse, realise that being able to write 6,000 characters by hand is overkill and lower the bar. You’re the one learning the language, you know best what you need!

I’ve written a lot about learning characters here on Hacking Chinese, apart from the articles I’ve already linked to. Here are a few that I think are particularly relevant and that I recommend as further reading:

A minimum-effort approach to writing Chinese characters by hand

Editor’s note: This article, originally published in 2012, was rewritten from scratch in June, 2022.

34 comments

Thanks for the article, I liked it.

So you know MORE than 5,000 hanzi? That’s insane! How many do you know exactly? (passive recognition / can write at least mentally). How did you get to learn so many, is that really the number of characters you encounter if you read a lot?

“Don’t just look at the characters and say “I know this” and click “next” […]”

I hope there aren’t any more people out there who review from character to meaning…

I have a confession to make. I finished learning the 2,000 most common characters for Japanese almost one year and a half ago now. Even when I was learning, I wrote by hand most of them only one time. But the worst thing is, since then, I never ever wrote a single word of Japanese by hand… My handwriting must be terrible. I probably have one of the highest (knowledge of Japanese)/(characters written by hand) ratio ever… And for Chinese, well, the sole character I ever wrote was 你, I believe… How bad is that.

(However, when SRSing my characters, I ALWAYS write them in the palm of my hand with the finger (mostly in the subway, ahah), and according to Anki, that’s 32,120 finger-written characters as of today, so I’m probably not completely bad at that little game… Rather than now knowing, it’s more like the proportions would be weird if I used a pen).

I plan to work on by handwriting skills one day, but that’s really, really low on my priorities. I just can’t feel this same “urge” that I have to learn more vocabulary, more grammar, read and listen more.

If you read reasonably often and read different kinds of texts, I think you get to 5000 without trying very hard (meaning that you don’t have to really look for hard characters). However, after this I’ve found that you either need to start reading things with lots of 成語, texts with specific vocabulary or with lots of place names. It seems like most new characters I see that I don’t already know at least passively are either names of places or food. I usually don’t bother to learn those unless I have a specific reason.

I think I know about the same amount of characters as you (around 5,000); have you noticed how the only new characters now are in place names and given names? It’s incredibly frustrating that I can read aloud every character in some text, but then when it comes to a person and his village’s name, there will be some crazy, ridiculously uncommon character. Memorizing and retaining them is also not easy, since they have no surrounding context of worth.

When I’m learning a new word, I usually start out by writing the new character five times and saying it out loud. Subsequently, each day, I write out the entire list of new words strictly from memory, without looking. If I forget a word, I review the dialog that goes with the vocabulary list and see if I can recreate it from memory and dredge up the forgotten word that way. Any words I just can’t recall, I write five times on that day to try and remember them better for the next day.

By the end of the week I’ve usually got pronunciation, meaning, character recognition and writing fairly solid on about 10 minutes a day. I still find I have to go back and review from time to time, as small pieces of a character fall out of memory, but that review seems to solidify and put things into a long-term memory at that point.

I personally think the writing really does help distinguish similar characters from each other, as well as helps put the character into more long-term memory. If I’m struggling to remember the character, sometimes if I just write it on a piece of paper, the muscle memory and stroke order kicks in for me, and it suddenly comes right out.

If I just look at characters (tried that early on) they more easily evaporate or get confused with others.

Maybe it’s just me, I am after all only a beginner, but I don’t find learning to write them taking any more time than learning them period since I combine them all into the one exercise.

Renee your method looks like an improvement on mine. I’m going to start using it and hopefully more characters will stick in my brain. 🙂

I agree with you that learning characters to write characters above a certain set to start with is probably not a good investment of time. Nevertheless, I’ve always loved writing characters itself, no matter how limited the use.

Brilliant, thoughtful post. I’m really curious as to how handwriting skills are changing in China now that there are so many apps and other ways to write. A project of mine here is finding the remaining brushmakers in China, and the ones I’ve met all complain that no one uses brushes every day, so it’s no longer a good way to earn a living.

This area is one that I’ve personally had several different opinions on over the years. For the first few years at school, we had to handwrite everything. Personally, I thought all the time spent learning characters would have been better spent I the other foundational areas. While I can read around the three or four thousand character mark, I can only write about 1200 by hand. Still, as a personal goal I want to be able to write about 6000 or 7000 characters. As for students, I think addresses and locations are probably the only thing that one absolutely needs to learn to write. Still, good luck on the quest for an answer.

I agree this is an important question to confront maybe at various points in one’s Chinese learning ‘career’. I don’t do much of any writing these days. I do remember fondly when I was copying sentences by hand somewhat regularly as a way to practice not just writing, but other skills too. Because writing slows you down, the sentence I was copying – the sound of the sentence as if they were spoken – would repeat naturally in my head as I would write. I felt I was internalizing language this way. And I find it peaceful and meditative to copy sentences.

I agree with this article, and wouldn’t object to someone feeling writing is dispensable. At the same time, I would be surprised if you could find a student of Chinese who spent a lot of time writing and feels regret about it.

I don’t have a Reddit account, so I am going to post my own answer to the ‘you should learn handwriting to improve you ease in reading’ argument.

When I was a beginner, I did invest in handwriting. I never was able to hand-write more than 500 characters, but that was enough to get the principles such as ‘radicals’ and ‘stroke order’ down. It’s been so long since I’ve practised that the character I can hand-write from memory now is probably much lower.

I am pretty comfortable with using a stroke-based paper dictionary even with my atrophied hand-writing skills.

Now, ‘reading Chinese with ease’ is an imprecise metric, so I’ll be more specific – on most days I read over 100 pages of Chinese (mostly fiction) without inconveniencing myself. Whether I can read it with ‘ease’ depends on the difficulty of the writing, as well as the familiarity with the relevant vocabulary. I recently breezed through a Gu Long novel, but I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t be able to read a Wu Wei novel with ease yet (she sprinkles her novels with a lot of classical Chinese and historically-specific vocabulary)

I can read most kinds of fiction at about 80-90% of the speed I would read the equivalent text in my native language. If I tried to read a financial analysis in Chinese, that percentage would be much lower, but I think the way to fix that would be to improve my financial vocabulary and actually read a financial analysis or two in Chinese, not work on my hand-writing.

I think hand-writing is a worthy skill in its own right, and I actually would like to return to it when it is a higher priority for me. However, I think the ‘without hand-writing you won’t be able to read Chinese with ease’ argument is rubbish. If one’s goal is to read Chinese with ease, my recommendation is to read 100 bloody pages of Chinese per day (or if that’s unrealistic, work oneself up to the point that it is realistic).

Thanks for analysing this aspect of Chinese. Very good article3.

I am finding that when you are in meeting or in class (on any subject) it is more efficient to take notes in the language spoken rather than translate what is being said into English. I am wondering if takes a long time to learn to take notes in Chinese to the extent you can do so without having to think too much. Or is it the case that there will always be some characters where one has to stop and think oh how do I write that and by that time the topic has moved on. Whereas in other languages you can always down write the word and look it up later, but at least the notes will be clear.

I don’t know. I’m sure you can learn to take notes without too much problem in Chinese, bit I usually don’t think it’s worth it, just takes too much time to write. It’s not that I don’t know the characters, it’s just that I haven’t written enough to be able to take notes continuously while focusing on what the lecturer says at the same time. I take notes in a mixture of languages: Swedish, English, Chinese (both pinyin and characters). I think being able to write things down in several languages is an advantage and I don’t really see why taking notes in English would make the notes less valuable, provided that you know the relevant vocab in both languages. Also, a significant part of the academic literature is actually in English anyway, so even if the lecturer speaks Chinese, it makes sense to take notes in English.

Thanks for sharing your experience on this.

You are probably “write”, one could take notes but it would take a lot of time to practice for it to become second nature as it were. I am finding it takes longer to write in Chinese so that even translating into English and writing it in English is quicker, and even that can be a long process during which you are trying to understand contents. Note taking is probably a skill too.

I don’t really practise character writing but I do know the stroke order. I currently live in Hangzhou where none of the taxi drivers speak English and don’t know pinyin as they didn’t grow up with that. By far the most crucial reason for me to know how to write characters is when I see my phone is about to run out of battery. I write down the place name, my phone dies, I show the note to the taxi driver and all is well. Apart from dead battery, I’ve found little use for character writing.

Great article for any learner and teacher. First, How long ago did you started thinking really about to write or not the Chinese characters? And, for a beginner what do you recommend, even though they really don’t know at this time their goals and how long will they learn? Myself, I study Chinese sinc.e 2008, and also know Armenian, Spanish, Portuguese, German , English and some French. I’m looking forward to keep learning and know have the opportunity to teach Chinese as a foreign language but, more than 5 different jobs requests all demand me not to teach Hanzi, characters and to write. They say is useless for they employes to learn handwritten language, but I don’t agree. What do you think is the best outcome teaching only by pinyin?

I’d like to point out that you do not need to learn to write by hand if you want to pass the HSK 6. Just find a test center which offers the internet based test, there you’ll be able to type (using pinyin input method). I learned this today and it blew my mind. I’ll now first learn how to read and learn the hand writing later at a low pace.

I have been four months in Taiwan, and I am taking a Chinese course, and I understand I love learning Chinese, but I hate to write (this consume a lot of time and effort); that no made sense because I am a professional guy where only I need a computer and phone.

The problem is that the university takes me up writing exam! And I have insufficient qualifications, haha.

And I am trying to figure out if I need to write “for learning” because I use flashcards (help me memorize).

By the way, my goals are talked, reading, and listening.

good article!

Yeah, sometimes learning goals are imposed on us by other people. I want to maintain the ability to write by hand for many reasons, but that doesn’t apply to many students. Ideally, Chinese course should allow students some leniency and let them choose what they want to do. Some teachers I had while studying Chinese in Taiwan let people do 聽寫 with a computer, for example, but far from all! For many teachers, skipping handwriting (or cutting down on it) is just not an option.