What’s the best way to learn Chinese characters as an adult foreign learner? This is a complex question we definitely don’t know the full answer to yet, but that doesn’t mean we have no clue. In this article, I will talk about my most ambitious attempt to teach

We know some things that are important for learning in general, such as understanding (as opposed to rote memorisation), and active retrieval (as opposed to passive recall). Thus, a good method will involve learning the meaning of components and how they form compound characters. It will also involve an active approach where you need to actively retrieve and use what you have learnt.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

Then there are other things, such as spaced repetition, which are uniquely well suited for learning Chinese characters. There are also many things which are not well suited for learning Chinese characters, some of which I listed in my article How to not teach Chinese characters to beginners: A 12-step approach.

There are many methods that follow these principles, and since individual factors and preferences are also important, it’s hard to say that one method is strictly better than the others. Some people love being creative with mnemonics, others prefer more traditional methods.

For me as a teacher and educator, the question of what method for learning Chinese characters is the best is of more than just personal interest. Indeed, it’s something I’ve been thinking about over more than a decade of teaching Chinese and writing about learning the language.

My thoughts on the topic have changed over the years, but have come to rest recently. A while back, I started working on a Chinese character course for Skritter, which forced me to systematically look at the challenge of beginner character learning and figure out the best possible solution. If you’re not familiar with Skritter, it’s an app for learning Chinese and Japanese, and you can check my in-depth review here:

While not perfect, I believe that the final result of this project, The Skritter Chinese Character Course, is as close as I’m likely to get. In this article, I’ll share some thoughts about the course itself, but also about what it was like creating it. I’ll also show some excerpts from the course itself and how you can access the full course for free!

The Skritter Chinese Character Course

The course is aimed at beginners, ranging from those of you who don’t know a single Chinese character to those who have learnt a few hundred, but without really understanding how the writing system works. More advanced students would benefit more from other courses, such as the one offered by Outlier Linguistic Solutions.

The course consists of 16 video episodes, each roughly 6 minutes long, covering a wide range of topics presented in a carefully designed order. Here’s the first episode where I introduce the course:

Here’s the full syllabus (the link goes to the relevant section in Skritter, and you have full access even during the trial period):

The Skritter Chinese Character Course

- Introduction (see above)

- Pictographs

- More Pictographs

- Simple Ideographs

- Stroke Order

- Semantic Compounds

- Character Composition

- Shapeshifting Characters

- Complex Pictographs

- Phono-semantic Compounds

- More Phono-semantic Compounds

- Even More Phono-semantic Compounds

- The Chaotic Nature of Chinese Characters

- The Most Common Chinese Characters

- Word Formation

- Character Variation

Here are a few examples available on Skritter’s channel on YouTube:

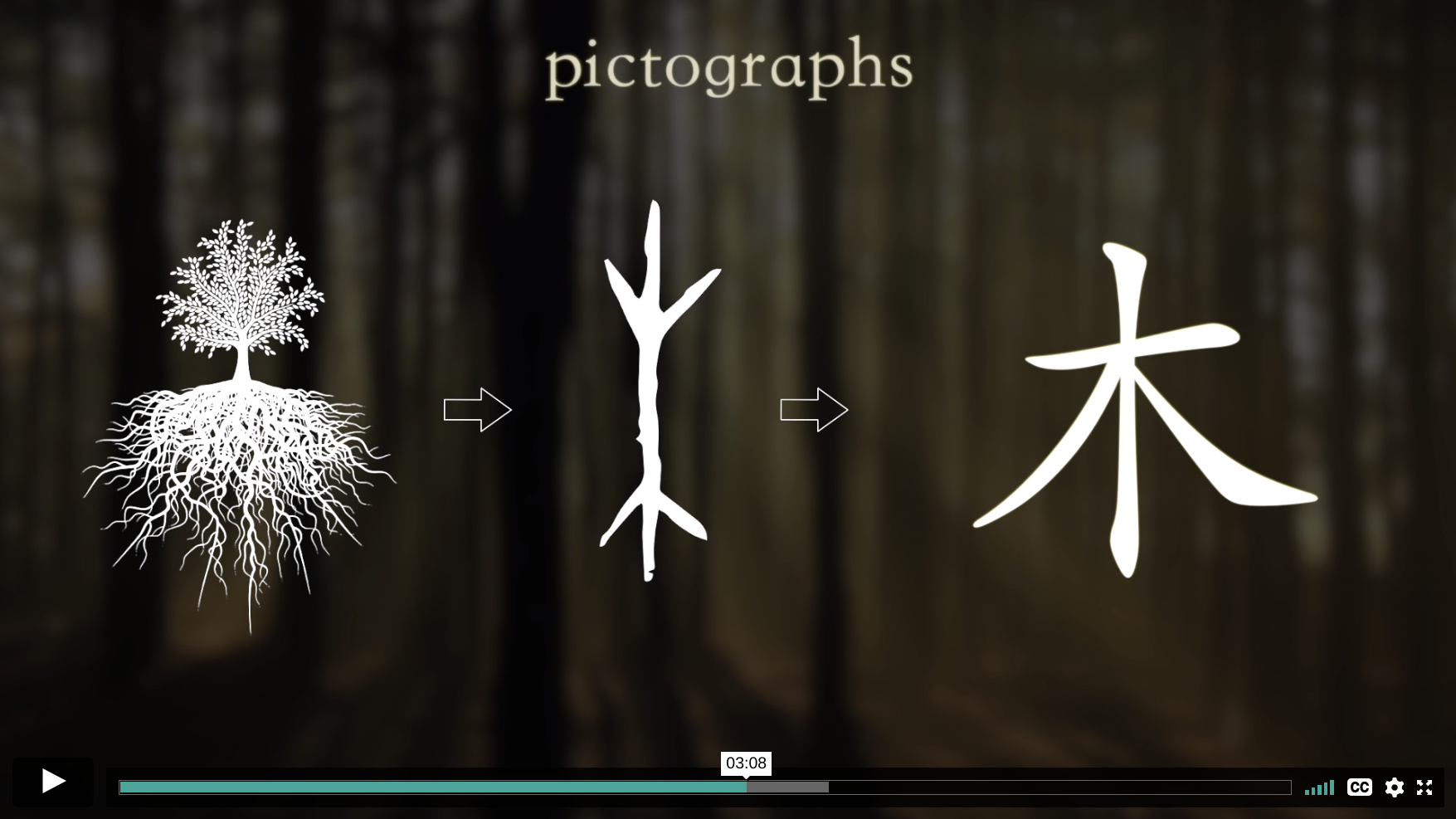

From Episode 2: Pictographs

From Episode 9: Complex pictographs

From Episode 10: Phono-semantic compounds

While I’m the architect behind the approach and content of this course, the final product is a team effort. I would never have been able to produce video and graphics of this quality, and the content wouldn’t have been as optimised without feedback from team members and students.

Another thing I can’t do here on Hacking Chinese is combine great content with a tailor-made technical solution. Skritter is built on fifteen years of experience creating software for teaching Chinese characters, which is important, because just watching videos won’t really teach you characters, you have to actually write characters. Naturally, you could do that on paper, but digital handwriting with corrective feedback and spaced repetition is much more powerful in the long run.

The course i s provided at no extra cost for all Skritter subscribers. If you’re already using Skritter, just use the link above to access the course. If you’re not using Skritter, you can still start a trial, which will give you full access to all features and content, including the character course. If you like Skritter, you’re welcome to stay subscribed, but if you just want to check out the course, you can easily finish it before the trial is over.

If you do end up subscribing, using this link or the code HCSKRITTER will give you 10% your first payment and will also help support Hacking Chinese!

Key principles in the Skritter Chinese Character Course

When designing a pedagogical project like this, I think it’s important to be clear about what the key principles are, because they will underpin every decision you take throughout the entire project. I have already mentioned some important insight about learning above, but here are some more specific things I focused on when designing the content:

- Healthy balance of theory and practice – The goal of the course is not just to teach you the most common characters (we do teach 150 very high frequency characters and character components), but also the necessary theory to understand how they work. This will enable you to learn thousands of characters later.

- Only extremely useful characters – I have spent dozens of hours planning the exact sequence of characters used in the course. I refuse to use rare or obscure characters to prove a specific point. All characters that are introduced in the course need to be immediately useful for beginners.

- Logical and coherent sequence – Every episode in the character course builds on earlier episodes. At no point are you required to know something that isn’t explained in an earlier episode of the course. This is not easy to achieve, and I’ll say a few words about it below.

- Simple but not to the point of being misleading – Chinese characters are very complex and it’s impossible to teach everything in 16 short episodes. This means that pedagogical models and explanations need to be distilled to present the essence, but without being misleading. Making stuff up because it’s cute or sounds good is not an option.

- Built-in repetition and consolidation of learning – While you’re supposed to practise writing the characters taught in the course as you progress through the episodes, there’s also plenty of reviewing built into the episodes themselves. We use a purpose-built tool to make sure that we recycle characters and components as much as possible to optimise the learning experience.

There are of course many more important principles for creating good learning materials, but these are the ones that are the most specific to this course in particular.

For most of you, knowing the above will be more than enough to tell you if the course is worth checking out, but since I like reflecting on things I do, especially big projects like this, I will now share my thoughts on two challenges I faced when developing the course. This might be interesting for other teachers or just curious students.

Course development challenge #1: Building a pyramid with no missing blocks

One of the main challenges when planning the content in the course is the sequencing of ideas. As mentioned above, the goal is that you should be able to understand everything in the course based only on what you have learnt so far. This might seem trivial at first, but it’s not.

For example, how do you teach stroke order if you only have 20 characters available? The answer is that you plan the characters very carefully and teach stroke order only when you have taught characters that can illustrate the rules you want to teach.

Another example is compounds. How do you teach compounds without flooding the student with new components and characters? You plan the sequence very carefully, so that components taught in earlier episodes appear in later episodes to form compound characters.

This turns course development into a huge jigsaw puzzle, where moving a single character around can disrupt the flow in other parts of the course. Characters are introduced to serve multiple purposes at once, some of them not being obvious until much later in the course

Course development challenge #2: Remembering what it’s like to not understand

The Chinese writing system is very different from English, which is easy to appreciate for anyone who has learnt both. Obviously, to design a course like this, you need to know how the writing system works, but you also need to remember what it was like not knowing how it works, because otherwise you can’t explain it in a way that makes sense to beginners.

A central idea I settled on early is to present the writing system in phases of complexity, starting from pictographs, moving on to ideographs and then to compounds of various types. This sequence is presented as a journey through time, where the student gets to follow the thought processes that might have led to the writing system we have today. The goal is not to teach the actual history of how characters developed, that’s much too complicated and not very useful for beginners, but to show that the writing system actually does make sense if you look at it from the right angle.

Along the way, I use various analogies I think are good for explaining certain aspects of written Chinese, such as using numerals in English to show that we also have symbols that mean things and are linked to a spoken word, but where this is not visible in the written symbol. You have to learn that “3” is pronounced [θriː] and there’s nothing in the shape of the numeral that indicates this, just as there’s nothing in 木 that shows that it’s pronounced mù in Mandarin. Both symbols have some link to their respective meaning, although it’s not obvious if you don’t know it in advance.

Concluding thoughts about the Skritter Chinese Character Course

I found it challenging and immensely satisfying to work on the Skritter Chinese Character Course. It was in production for a long time and has been out for a while now, but even so, I don’t look at the episodes now feeling that we should have done things differently. Of course, there is always room for improvement, but on the whole, I’m very happy with the result.

I would have given a lot to have a course like this available when I started learning Chinese. It encapsulates most things that you have to know to be able to learn characters effectively, and this knowledge and guidance are typically not found in most textbooks and courses. Some of these things took years to figure out, but they should have been available from the start. I don’t have a time machine, so I can’t go back to 2007 and show the course to myself, but at least I can make sure that people who start learning Chinese now have an easier path towards mastering Chinese characters!

Check out the Skritter Character Course here!