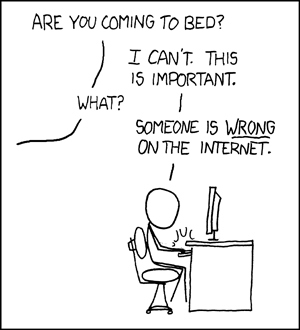

The best way of handling most things you don’t agree with on the internet is to simply ignore them, an approach that is much healthier than giving in and trying to correct every wrong and straighten every question mark you see. Considering how much dubious material there is on the internet (and elsewhere) about learning Chinese, I would surely die without this strategy.

Chineasy and Learn to read Chinese with ease! have received so much attention lately and I receive so many questions and comments about it that I need to write this.

Learn to read Chinese with ease!

So I tried ignoring ShaoLan’s Learn to read Chinese… with ease! and similar discussions about learning Chinese characters, but since I still receive recommendations to watch her TED talk (mostly from people who don’t study Chinese) and questions about the content (mostly from people who do study Chinese), I think it’s time to write a little bit about learning to read Chinese.

I’m not going to bash either ShaoLan’s TED talk or her product (which I haven’t seen); this has already been done by others. Instead, I’m going to address some questions related to the content of her talk. I’m also going to expand on my answers and discuss how some of the difficulties with learning to read Chinese can be overcome.

Please note that even though I use ShaoLan as an example here, what i say ought to apply to a lot of other people and products as well.

First, let’s have a look at her TED talk, which is only six minutes long:

Learn to read Chinese with ease?

In general, I think being encouraging and optimistic about language learning is good, even if some difficult and depressing facts are ignored or brushed over. This is especially true for Chinese, which has earned a reputation for being impossible to learn, which is evidently not true. Even though I think the claim that learning to read Chinese is easy while learning to speak is hard is exactly opposite to most people’s experience, I’m not going to dwell on speaking Chinese now.

Instead, I want to address an issue which is common in product introductions and advertisements (not just the above TED talk), namely that of numbers relating to reading ability in Chinese. The claims are different in different sources, but these are from ShaoLan’s talk:

- A Chinese scholar knows 20000 characters

- 1000 characters will make you literate

- 200 characters to read menus, basic web pages and newspaper headlines

- Chinese characters are pictures

I’ll address these one by one. In some cases, there are no exact answers, but I’ll try to provide different points of view here, as well as my own opinion.

Chinese has a bazillion characters

For some reason, it’s quite popular to first scare students and say that there are 20000 or 50000 characters, making Chinese sound impossible. However, the truth is that most Chinese scholars certainly don’t know 20000 characters. That’s a ridiculously high number and the only ones who will stand a chance of reaching that are people who spend serious time focusing only on learning as many characters as possible. Divide the number by three and you get closer to the number of characters university educated Chinese people actually might recognise.

You don’t need that many characters to read Chinese

The next step to make your product look attractive is to make the amount of characters you actually need to learn look really low, which is much easier if you start with a very large number. It sounds much better to first say that Chinese scholars know 20000 characters and then say you actually only need to learn 1000 (5%), rather than go from 6000 to 3000 (50%), doesn’t it?

There are different numbers, but I think 2000 is the most common one, but ShaoLan chose 1000. Whatever the number is, it’s usually followed by a percentage telling you how much you can understand of Chinese text knowing that many characters. In the case of 1000 characters, it’s 40% in the video.

The problem is that any such comparison is completely meaningless. In Chinese, meaning is conveyed using words and most words consist of two characters. Thus, knowing a certain amount of characters isn’t directly related to reading ability at all. For instance, if you know that 明 means “bright” and 天 means “sky” you will have no idea that 明天 means “tomorrow”. This is not apparent from the constituent parts of the word, although knowing the constituent parts certainly makes it easier to learn the word.

Characters and words are not the same thing

Furthermore, even if you did know all words that could be created with all the characters you know, it still wouldn’t tell us much about your reading ability. The problem is that if you know the most common 1000 characters, you’re bound to know a lot of common pronouns, nouns, verbs and particles.

However, these are rarely the key vocabulary in sentences. Knowing 50% of the words in a sentence does not give you 50% reading comprehension! It might actually result in 0% reading comprehension in some cases and perhaps even more than 50% in others. Unless you’re reading fiction where there’s a lot of fancy adjectives and adverbs, I think not knowing key components in a sentence tends to reduce reading comprehension a lot more than the percentage of characters you know implies. See this article for a deeper discussion about reading and understanding.

Apart from this, there’s also grammar and a lot of other things to learn which aren’t related to the number of characters you know either. To sum things up, learning a certain amount of characters will have little direct effect on reading ability (although the indirect effects can be substantial).

200 characters to read newspaper headlines?

This claim is somewhat unique for ShaoLan, I think, and I have no idea where she got this from. In my experience, headlines are often the trickiest part of a newspaper article. When I took a course in newspaper reading in 2009, we usually saved the title until after we read the article because it only made sense for us when we already knew the story. 200 characters won’t take you close to understanding newspaper headlines; 2000 probably won’t either. This claim is so ridiculous I don’t really know what to say.

The same is true for menus, but in a different way. The problem with menus in Chinese is that there are so many characters that are only used for food. I don’t really care that much about food and haven’t bothered to learn some infrequent food characters, so I find menus confusing even though I can write about 5000 characters.

Approaching a menu with the 200 most common characters will probably only give you hints for a small part of the menu and will most likely only tell you if it’s rice, noodles or soup. If you’re lucky, you might be able to deduce what animal has died to provide your meal.

It would be interesting to take a few menus and see how many of the characters on them fall within the 1000 most common characters. If you have a menu and some spare time, feel free to contribute! Let’s use this list for frequency data. If you want to know more about roughly what you need, you can start with this article over at Sinosplice.

Chinese characters aren’t pictures

I’m sorry to say this, but Chinese characters aren’t pictures. Yes, there is a (very) small percentage of characters that originally directly represented objects in the physical world, such as 日 “sun” and 月 “moon”, but these characters make up a small fraction of characters in use today. I have several books that teach Chinese characters through pictures, and the problem with all of them is that they are mostly cherry-picking easy cases that make good pictures.

You can probably learn a few hundred characters this way, but the problem is that the characters you learn are not going to be the most frequently used characters. All of the discussion above about what you can use characters for assume that you’re learning the most useful characters, not the ones that are easiest to make cute pictures for.

For instance, while it’s true that 囚 means “prisoner”, this character doesn’t appear in the most commonly used 2500 characters and will help little to increase your reading ability. The same is true for 姦, which is actually a traditional character (simplified is 奸). Bot these are easy to show in pictures, but won’t actually boost your reading ability at all.

This reminds me of something else. If you’re learning Chinese, you should choose to learn either traditional or simplified characters and stick to one set until you know it relatively well (it doesn’t really matter which you choose). You can learn both sets later and it’s not very hard, but choosing one or the other on a character-by-character basis because one might be easier to learn than the other is not a good idea (for instance, ShaoLan uses traditional 姦 but simplified 从).

Learning to read Chinese is not easy

This should come as no surprise to anyone who has learnt to read Chinese. Still, the point with this article isn’t to discourage you and say that Chinese is impossible to learn either, but I do think a that a measure of realism is needed. Learning a hundred pictographs and combinations of such isn’t all that hard and there’s nothing really new with that method.

But what about the rest? What about the remaining 3000 characters you need to approach actual literacy? Here are a few things you can do to boost your character learning and make learning Chinese possible, although it will still take a lot of time:

- Most Chinese characters (around 80%) are combinations of meaning and sound. Learn how these characters work and you will save yourself a lot of time and trouble. I have written two articles about this:

Phonetic components, part 1: The key to 80% of all Chinese characters

Phonetic components, part 2: Hacking Chinese characters - Use clever memory techniques (mnemonics) to learn characters. This is not something new, it’s been practised basically forever, but our understanding of why and how mnemonics work has improved immensely. I have written about this many times:

Memory aids and mnemonics to enhance learning

Remembering is a skill you can learn

Creating a powerful toolkit: Character components - Don’t rely on rote learning if you can avoid it. There are some thing you will have to rely on brute force to learn and that’s okay, but whenever you can, try to make learning meaningful. If you want pictures like those used in the TED talk above, Memrise is a good place to start (it’s also free). In any case, avoid rote learning. It might work, but it’s horribly inefficient.

You can’t learn Chinese characters by rote

Holistic language learning: Integrating knowledge

Conclusion

Learning to read Chinese is not impossible, but it’s not easy either. Exactly how difficult it is depends on a lot of factors, some of which are beyond your control, but ShaoLan definitely has a point when she argues that learning Chinese needn’t be as hard as people think. Personally, I don’t like the way she does it; it looks way too much like someone trying to sell a product regardless of the truthfulness of the sales pitch.

Moreover, cherry-picking examples to prove your point isn’t very good, although I have made myself guilty of that as well. Still, if this makes people just a little bit more optimistic about learning Chinese, making them start learning the language or keep on studying even if it feels impossible at times, I’m not really complaining.

31 comments

Yay for some smart anti-Chineasy writing!

I’d be harsher than you in the overall judgement – and I think that faux-panaceas such as this one are actually quite harmful. On the one hand, they make politicians, corporates and fund-allocators believe that you can ‘do it more simply’ – and has real risk for serious programs, or those of us trying to put together more modest and effective methods for learning. On the other hand, rather than encouraging, I think that badly managed expectations can actually deter people forever, and create a depressing sense of inadequacy ‘how come I failed, when it was supposed to be so simple’? I for one generally tell my students what they’re doing is incredibly hard :-). Maybe that’s a different take on learning psychology.

I mostly agree with what you say, but I think other people (most notably Victor Mair) has already discussed the obvious shortcomings of the approach, so I chose to focus on other aspects. The only part I’m not sure I agree with you on is whether or not this will really deter people from learning Chinese. I think it’s questionably that someone will think Chinese is easy just because of this. Most normal people will realise that learning any language is a time-consuming task. Even if they do, I think we gain more people who try Chinese, like it and stay than we lose through disappointment. In short, I think we get more people learning Chinese like this, which is good. I still don’t like the way it’s done, though.

Yes, her TED talk is quite irritating.

It seems to me that very few native Chinese speakers, including those who hold CSL qualifications, have much of an idea about how non native speakers learn Chinese. Even worse, they don’t have any curiosity about how it’s done either.

‘Bout time you and the guys at Skritter/Anki get together and do a TED talk yourselves…??

I agree, but the problem is that more realistic ways of learning don’t make good headlines. Saying that you can learn Chinese in three months or that learning to read Chinese is easy sound much better than learning Chinese in two years and learning to Chinese is actually pretty hard, but there are some things you can do to make it easier. I think people who are already into Chinese will care more about things that actually work, though, but these tasks are obviously direct at people who have never learnt Chinese and probably never will either. Sorry, but I’m a bit pessimistic in this regard. 😀

I’m so glad you brought this up! I constantly get recommendations on her work and TED talk and I’m sick of it. She is everywhere lately, the funny thing is that I don’t think anyone who is studying Chinese seriously believes on her method, but she still managed to convince everyone else. I won’t deny her pictures are pretty and maybe a nice and soft way of starting with Chinese, but nobody should rely on her method if they are serious about learning this language.

Thanks for this articule!

Teresa

Thanks Olle for this article! I too get sent her stuff regularly and it’s frustrating to have to be the one to explain that no, Chinese isn’t as easy and beautifully logic as she paints it to be. We can definitely definitely find ways to make the learning process easier…just maybe not hers!

I think Shaolan herself knew she wouldn’t get backed by “serious” Chinese learners (i.e people who actually learn Chinese); why would she have put her project in the “design” category on Kickstarter otherwise? Also, she mostly applies for Design awards…Rightly so, her designer is really good!

When I started out trying to learn Chinese on my own, I fell for some of these more naive methods, and marketing methods.

Way way back, when I was still under the illusion that having a Chinese speaking girlfriend meant I could pick up Chinese easier than everyone else. I remember thinking I could download a list and memorize it. Then, I would be a hundred times awesomer. And even back then, there were blogs, and people telling me it was “easy.” Nowadays, I still see these lists as useful, but not in the same way. I see them more as one of many ways to check my progress. Nowadays, I also compile these lists myself. I don’t trust as easily anymore. When using these lists, I ask myself questions like “How many different words can I use that character to create?”

As far as the products go. Again, way back before I started seriously studying. I remember reading a blog where a non-multilingual person was singing the praises of Rosetta Stone because he met an eastern european girl who sounded “Perfectly American” after using it. After hearing this from a stranger on the internet I had to go check it out. The guy selling it at the Mall said things like “You only need X words for basic conversation” and “this product teaches you through images and sound, no english, so you learn like a native” and so on. I thought it was right for me and I bought it, and started learning it. It was useful, but far from perfect, and for sure not the only learning tool I would ever need. I still remember when I finally figured out that 窗户 wasn’t apartment, several lessons after I had learned the term.

—-

I guess the big questions that this article brought up for me to you are:

What is your 5 minute pitch to encourage people to learn Chinese without making it sound too easy, or too difficult?

Would you discourage beginners from trying to learn by frequency lists?

Is there a program, or a method to take one of these lists and push all the characters through to find all/most/some of the “common” word permutations and grammar that could be created from the list and turn learning by list into something more useful?

I think there are several things that are quite easy in Chinese, such as basic grammar and reaching some kind of conversational level. I think the best encouragement is to focus on the easy parts and not mention or at least not highlight the really hard ones. Focusing attention is not the same as misinformation, I think. Regarding frequency lists, I think they are great as support for learning or for plugging gaps, but my general advice is to only use lists that target a level below your own, so I usually advice against using lists to extend your knowledge.

I didn’t resist to give my 2 cents.

Based on my own experience I do think it’s easy, when I learned kanji I speed up everything, it was all quick and dirty, from the mnemonics to the components, and I don’t even put a lot of them in anki because I wanted to starting learning words asap. But despite all of that here I am, all literate.

That’s natural, after all we are learners, we don’t pick words from our mothers we pick from the text or the dictionary, if we know a word we can also read it.

You said a big truth about kanji≠reading. I don’t actually know many kanjis (their isolated meaning) but I can read the words that use them just as well, so I don’t even bother.

That being said I want to give another view, I understand that outside of our little language learning sphere learning Chinese is difficult, but that’s nothing to do with Chinese or anything. The big truth is: People simply doesn’t know what learning is. In other words, they can’t distinguish what is actual learning and what is just decoration. Let me picture a sarcastic example:

1- learnchinesein1second.com launches its new smartphone app, it cost just U$50 a month which is nothing compared to the benefits (or so the creators say). You starting learning to write hanzis like “hao” and “wo”. You draw them on the screen with your finger and moves to the next, there’s no review, you just move following a list, but there’s a cool xp system that shows your “progress”. But wait! There’s more! There’re also a lot of awesome games and “cultural” content, that are completely essential to the method and aren’t a waste of time at all.

2- Poorramdomstudent doesn’t buy the app, he decides to user another method, which is of course inferior, after all it’s free. He download a deck with 3000 hanzis on anki, he puts the hanzi on the answer to recall them from his memory not from the screen, write them once on a real paper, grade the card and let anki take care of not forgetting them.

Of course 2 is the best, but most people would fall into 1. That’s something that happens with everything, people going to the gym when they can just ride a bike, buying piles of textbooks to collect dust, spending hours on forums to collect “useful” resources they’ll never use. They believe that whatever it is, it can’t be made on your own but if you just throw money at it then everything becomes possible.

为时不晚 – wéi shíbù wǎn – it is not too late…..

Wise words, isn’t it? To link with the (marvellous) article, please let me add that once we realize that Chinese is not actually a biblic monster, in the end is just a matter of getting started.

Thanks for the article and the link to Victor Mair and the awesome Language Log (best comment snark: “So it’s Cheesy?”). Though I’m surprised by VM’s own “Chineasy” slip: “Chinese is the easiest language I ever learned to speak”. That’s pushing it!

It’s a relief to read your post, as until now I only had a short Skritter thread to point people to. And I felt like a grouch for failing to enthuse about the nice Chinese lady with the pretty, clever drawings.

I just realized what bugs me most about her presentation: she illustrates a danger familiar to anyone who navigates between cultures: talking seductive nonsense about one world to a rapt audience from a different world, just because you can, and because there’s no one around to call you on it.

As Language Log writes in another post: “Your passport has just been stamped for entry into the Land of Bullshit” (line originally from Gawker).

To follow your article’s example and try to stay positive, I’ll add that, as a collector of Terrible Ways to Learn Chinese (soon available in your nearby airport bookstore), I’m impressed by this fun new technique, and I’ll admit Shaolan’s materials taught me a few mnemonics I wasn’t aware of. And learning Chinese may not be as easy as she says, but it certainly is fun.

Thank you for this. As a very long time student of Chinese, (I started in college in 1973),I am ever daunted by the difficulty of reading fluency. In the previous computer world, we would look up each fantizi character by radical and strokes and then try to find the right combination word. More than one person has suggested that I might be interested in this trivializing Ted talk. I have used the simplicity of pictographic characters to induce interest in the language, but it is little use beyond recognizing a few isolated characters and visualizing the history and culture of Chinese written language. Really learning a language and understanding the culture it represents is not an easy pursuit.

Chineasy won’t teach anyone Chinese, but it does generate interest in the Chinese language. For that reason, I view it as a positive contribution.

Thanks for this article, as a beginner I have been really excited by her approach and materials online. I’m glad that I was able to hear an alternate view on Chineasy.

I’m also grateful you mentioned only learning simplified or traditional at a time. I’ve been learning both, and while initially I was able to retain it, it’s become really daunting remembering both, as well as remembering which is simplified and which is traditional!

Traditional Chinese characters have more strokes than simplified.

Hello Olle! I am reading articles on your website already some weeks, so since I knew about your site and I have still so many to read! Is it possible for you to make/use an extension for making a friendly, printable version of any article – or maybe will you prepare a mobile Hacking Chinese version for easier reading on phones, Kindle, etc.?

Thanks for writing a great articles. It is my first comment here, but hope that not the last.

I don’t know if it’s just coincidental, but judging from various writings about Chinese learning or language learning in general I’ve been recently comng across on the net, there seems to be a backlash of sorts against claims of ‘easy’ or ‘fun’. And I think it’s healthy.

I myself realize I have been guilty of encouraging people to keep learning ‘fun’ on my site. When in fact, to get through the intermediate levels of learning Chinese, ‘fun’ is not necessarily the best slogan, nor is ‘easy.’ For my own part, however, my mistake is understandable because I wrote those things when I was somewhere in the middle of intermediate Chinese, and going with the flow, merely following your inclinations can get you through the elementary stages ok!

But I’ve come to learn that it doesn’t cut it if you are going to pass through intermediate on to advanced. Good habits and consistency, at the cost of other affective concerns play an increasingly critical role the higher you progress.

Unknowingly, unintentionally or otherwise, we do a disservice when we overplay things like ‘fun’ or ‘ease’ in our descriptions of learning – unless the learners target goals are more modest than becoming an advanced learner, and that’s seldom or never something we can assume is the case.

I think that we’re probably the wrong target market for Shao Lan’s book – her book (which I’ve bought for my kids) won’t teach you to ‘read’ Chinese any more than a colourful alphabet book will help somebody to ‘read’ English. But it’s great for the first step – recognising a few characters, and taking a few baby steps to realise that Chinese characters aren’t just random squiggles.

It helps beginners start out seeing Chinese as “fascinating and exciting, not weird and stupid” to use Olle’s words – and I think anyone who comes up with creative ways to do this should be aplauded. I agree with James. Even my mother-in-law can now recognise some characters.

I have been looking for years to try and find a free course on line. None seem to exist so my learning is hit and miss. I don’t need a pay course because there are days and weeks when I cannot study. My learning has not really progressed and sounds are non existent for me. i wish there was a simple organized course, not the hit and miss I have to use.

How about using a normal textbook and then hiring a tutor to help you through it? You could hire one only when you need to, of course, so it wouldn’t matter if you can’t study all the time. There ought to be thousands of courses online, by the way, although I have used few of them myself.

You can see similiar pictures in the stories of the app Zizzle. http://www.zizzle.io/free-stories

I have downloaded the Chineseasy app and finished all the 500 levels.

And i can tell you this,, i have learned more about the Chinese language in 1 month using Chineseasy than i did in 12 years in school while i was studying English.

The genious about the Chineasy approach is that they don’t explain too much, you just start and learn basics as you go, which is perfect for a beginner.

Psychologically, Chineseasy motivated me more to continue learning Chinese, even more so after finishing the 500 levels.

And that’s the reason i have started reading Hackingchinese in the first place.

I was really really disappointed to hear your opinion about someone who made me love the Chinese language.

She can connect with people & make people connect with the language, something not many people can do.

If you ever read my comment, i hope you give it a chance and take another look at it.

Thanks for your efforts here in Hackingchinese.

Hi Astro! Thank you for your comment! I should say first that this article is seven years old and relates to the product and marketing that was available back then, so it’s possible that things have improved since then. However, I think your comment tells me more about the dismal state of your experience in school rather than Chineasy! I think the reason many people working with Chinese language education dislike Chineasy is because of the disingenuous marketing rather than the product itself (see my comments in the article, which are still true). To really answer your question, I’d need to have a new look at the product, but it’ll have to fight for my time with hundreds of other resources I want to look at!

Hello again,

Thanks for reading my comment, I really appreciate that.

You’re definitely right about my school. I’m from the middle east and everything here is bad, especially education.

But i think it’s also about how learning languages is counted in hours, not years, as you said in one of your articles.

I just have seen that almost all the comments here was negative, and i just thought it wasn’t fair (although your article was pretty fair), and it might scare someone away from the app, effectively stopping them from learning Chinese, since Chineasy is easily the best app out there, IMO (most other free app made me quit after a day or two).

Anyway, i want to say thank you, because I’ve read in one of your articles about the Outlier dictionary, which have a short characters explanation, functional components and a relevent etymology (the same feature that i loved most about the Chineasy, because it makes it much easier to remember and create mnemonics for it).

My goal is to be able to read Wikipedia articles in Chinese by 2023, if that happenes, it’ll be all thanks to you and to Hackingchinese.

Yes, well put, it’s time spent engaging with the language that counts! There’s plenty of time to do that before 2023, so I wish you the best of luck! 🙂