Board games are more than just fun, they’re a powerful way to learn Chinese, boosting vocabulary, fluency, and communication skills!

I’ve used games extensively to learn and teach Chinese, and, at university, I also teach a professional development course for language teachers focusing on how to use games in the language classroom.

In this article, we’re going to have a closer look at what board games have to offer for learners of Chinese!

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode (#238):

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

Previously on Hacking Chinese

I’ve written several articles about this already, including how to use computer games to learn Chinese (and a separate article about StarCraft), as well as an article about playing word games to improve oral fluency. I have also designed text adventure games for learning Chinese.

In this article, I’d like to discuss board games and how they can be used to learn Mandarin. While I have written about Mahjong 麻將 (ájiàng), “mahjong” before, in this article I will focus on playing board games for language learning in general, even if the games themselves are not specifically related to Chinese.

Why board games are great for language learning

Board games are great for language learning for several reasons. Naturally, not all of these apply to all games, but by choosing the game carefully, you can get the right mix of features you’re after:

Playing board games in Chinese encourages you to focus on meaning and real communication. Students spend much too much time studying vocabulary and grammar for its own sake, and when speaking and writing, teachers encourage them to practice the words they’ve learnt, but not to practice the language, not to use it to communicate. When playing games, you use Chinese to communicate, which is necessary for effective proficiency development.

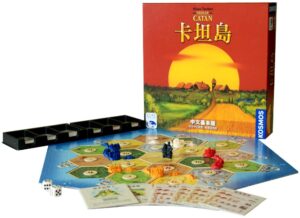

Playing board games in Chinese encourages you to focus on meaning and real communication. Students spend much too much time studying vocabulary and grammar for its own sake, and when speaking and writing, teachers encourage them to practice the words they’ve learnt, but not to practice the language, not to use it to communicate. When playing games, you use Chinese to communicate, which is necessary for effective proficiency development.- Playing board games allows you to repeat words and phrases without being bored. The language used in most board games focuses on a small cross-section of vocabulary. If you play Settlers of Catan in Chinese (卡坦岛 (kǎtǎndǎo), “Catan Island”), you’ll repeat the resource types 羊毛 (yángmáo), “wool”, 煤矿 (méikuàng), “ore”, 木材 (mùcái), “lumber”, 砖头 (zhuāntou), “brick” and 小麦 (xiǎomài), “wheat” until these words become second nature. You will also get good at using words for trading and haggling. A game with money in it will require you to use related vocabulary frequently. There are also many phrases that are common to many games, such as 该你了 (gāi nǐ le), “it’s your turn”. See the end of this article for a list of general board game vocabulary.

Playing board games makes language a tool for fun and entertainment. When playing a game in Chinese, the goal isn’t primarily to learn the language, it’s to have fun, win the game, or both, depending on what kind of player you are. This doesn’t feel like studying at all; instead, you’re using the language to achieve something. You can use your passion for games to read up on the game, understand the rules (in Chinese), and so on. Remember, having fun is important and long-term motivation is essential for mastery.

Playing board games makes language a tool for fun and entertainment. When playing a game in Chinese, the goal isn’t primarily to learn the language, it’s to have fun, win the game, or both, depending on what kind of player you are. This doesn’t feel like studying at all; instead, you’re using the language to achieve something. You can use your passion for games to read up on the game, understand the rules (in Chinese), and so on. Remember, having fun is important and long-term motivation is essential for mastery. Playing board games is social. Playing games is a good reason to meet other people (most board games do, of course, require more than one participant). While modern board games are not as popular in the Chinese-speaking world as they are in the West, there are still people who enjoy them. There are even cafés and clubs dedicated to board games (and I don’t mean only Chinese board games, I mean roughly the same games that are popular in the West). Find them! Relatedness is one of the basic psychological needs in one of the most well-researched frameworks for human motivation.

Playing board games is social. Playing games is a good reason to meet other people (most board games do, of course, require more than one participant). While modern board games are not as popular in the Chinese-speaking world as they are in the West, there are still people who enjoy them. There are even cafés and clubs dedicated to board games (and I don’t mean only Chinese board games, I mean roughly the same games that are popular in the West). Find them! Relatedness is one of the basic psychological needs in one of the most well-researched frameworks for human motivation. Playing board games allows you to teach and instruct others. Talking about games, or explaining the rules, is something that even beginners can do (depending on the game, of course). I remember explaining the rules of Carcassonne (卡卡頌 (kǎkǎsòng), “Carcassonne”) to fellow students in Chinese during my first semester of learning. I used a lot of gestures and pointing, yes, but it still worked. Explaining your favourite game successfully to a native speaker, or understanding how to play a new game someone has demonstrated in Chinese, is very satisfying! Teaching is a great way of learning Chinese.

Playing board games allows you to teach and instruct others. Talking about games, or explaining the rules, is something that even beginners can do (depending on the game, of course). I remember explaining the rules of Carcassonne (卡卡頌 (kǎkǎsòng), “Carcassonne”) to fellow students in Chinese during my first semester of learning. I used a lot of gestures and pointing, yes, but it still worked. Explaining your favourite game successfully to a native speaker, or understanding how to play a new game someone has demonstrated in Chinese, is very satisfying! Teaching is a great way of learning Chinese.

Which board games to play to learn Chinese

Naturally, your experience will be different depending on what game you play. The most important factor as a second-language learner (apart from whether you think the game is fun, of course) is how important language itself is in the game.

Some games involve little or no language. For example, you can play a game of chess without saying anything apart from “check” (將軍, jiāngjūn).

In other games, language is a crucial part of the experience. The classic board game Diplomacy (外交 (wàijiāo), “diplomacy”) is a good example, as the whole game revolves around talking with other players, forging alliances and planning how to backstab your friends.

Naturally, this type of game requires advanced levels of Chinese, whereas chess can be played without knowing a single word. This isn’t meaningless if you like chess, there’s plenty to talk about; it’s just not a requirement to play the game.

For a much more in-depth discussion about games and learning (or teaching) Chinese, check this article: How and why to learn and teach Chinese through games.

You need a source of proper language to play

When you play a game in Chinese, you need a good source for vocabulary and sometimes grammar. This will differ from game to game, so it’s hard to compile a complete list of useful words, but I have tried to gather generally useful words at the end of this article.

If you have a native speaker around, that’s, of course, ideal, but even if you don’t, you can still play because the rulebook is an excellent source of vocabulary.

I suggest that you start with a game you already know how to play in your native language, then read the Chinese rules (it should be possible to find these online if it’s a relatively popular game, or you can buy something locally) and extract all the language you need from there. You will internalise the vocabulary, sentence patterns and so on by playing the game.

For popular games, you can also find instructions in Chinese online. For example, in my article about Mahjong 麻將 (májiàng), I have included videos about the game. I also included the vocabulary you need to play the game.

Here are the rules for Settlers of Catan:

Video about playing board games in Chinese

Skritter has produced an awesome video based on this article. You can check it out below. It also contains some language you might need!

Learning Chinese by playing board games

I have played a number of games in Chinese and explained many more (because I’ve introduced them to Chinese-speaking exchange students in Sweden). This has been great fun and also a great way to learn and reinforce vocabulary and grammar.

Have you played any board games in Chinese? How did it go? Have you introduced any of your favourite games to your Chinese-speaking friends? Give it a try!

Vocabulary for playing board games in Chinese

General terms

| Simplified | Traditional | Pinyin | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| 桌游 | 桌遊 | zhuōyóu | board game |

| 色子 | 色子 | shǎizi | dice (also 骰子, tóuzi) |

| 掷色子 | 擲色子 | zhì shǎizi | roll dice (also 骰子, tóuzi) |

| 棋盘 | 棋盤 | qípán | board |

| 棋子 | 棋子 | qízǐ | counter, piece |

| 队 | 隊 | duì | team |

| 第一名 | 第一名 | dì yī míng | irst place |

| 第二名 | 第二名 | dì èr míng | second place |

| 轮到 | 輪到 | lúndào | turn (to the next player) |

| 开始 | 開始 | kāishǐ | start |

| 停止 | 停止 | tíngzhǐ | stop |

| 继续 | 繼續 | jìxù | continue |

| 计时器 | 計時器 | jìshíqì | timer |

Game actions

| Simplified | Traditional | Pinyin | English |

| 抛硬币 | 拋硬幣 | pāo yìngbì | flip a coin |

| 石头剪刀布 | 石頭剪刀布 | shítou jiǎndāo bù | rock paper scissors |

| 顺时针 | 順時針 | shùnshízhēn | clockwise |

| 逆时针 | 逆時針 | nìshízhēn | counterclockwise |

| 减一分 | 減一分 | jiǎn yī fēn | minus one point |

| 加一分 | 加一分 | jiā yī fēn | add one point |

| 得分 | 得分 | dé fēn | gain points; score |

| 洗牌 | 洗牌 | xǐpái | shuffle; mix |

| 发牌 | 發牌 | fāpái | deal (cards) |

| 换牌 | 換牌 | huànpái | swap cards |

| 加总 | 加總 | jiāzǒng | add up (the points) / The total (score) |

| 第一回合 | 第一回合 | dì yī huíhé | round one; the first round |

| 合计 | 合計 | héjì | total |

Some useful phrases

| Simplified | Traditional | Pinyin | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| 面朝下 | 面朝下 | miàn cháo xià | face down (on the table) |

| 面朝上 | 面朝上 | miàn cháo shàng | face up |

| 拿一张牌 | 拿一張牌 | ná yī zhāng pái | take one card (also 摸一张牌) |

| 轮到谁了? | 輪到誰了? | lúndào shéi le? | Whose turn is it? |

| 是我吗? | 是我嗎? | shì wǒ ma? | Is it my turn? |

| 该你了 | 該你了 | gāi nǐ le | It’s your turn |

| 游戏结束 | 遊戲結束 | yóuxì jiéshù | game over |

| 开始游戏 | 開始遊戲 | kāishǐ yóuxì | start the game |

| 下一个回合 | 下一個回合 | xià yī gè huíhé | next round |

| 我们是顺时针玩吗? | 我們是順時針玩嗎? | wǒmen shì shùnshízhēn wán ma? | Are we playing clockwise? |

| 我们算一下分数吧? | 我們算一下分數吧? | wǒmen suàn yíxià fēnshù ba? | Let’s confirm the score. |

| 你确定吗? | 你確定嗎? | nǐ quèdìng ma? | Are you sure? |

| 我可以看一下规则吗? | 我可以看一下規則嗎? | wǒ kěyǐ kàn yíxià guīzé ma? | Can I check the rules? |

| 我可以反悔这一步吗? | 我可以返回這一步嗎? | wǒ kěyǐ fǎnhuǐ zhè yī bù ma? | Can I take back my move? |

| 我的回合结束了。 | 我的回合結束了。 | wǒ de huíhé jiéshù le. | My turn is over. |

| 不准作弊! | 不準作弊! | bù zhǔn zuòbì! | No cheating! |

| 你能再解释一次吗? | 你能再解釋一次嗎? | nǐ néng zài jiěshì yí cì ma? | Can you explain that again? |

| 付2个硬币给银行。 | 付2個硬幣給銀行。 | fù liǎng gè yìngbì gěi yínháng. | Pay 2 coins to the bank. |

| 把你的筹码放在这里。 | 把你的籌碼放在這裡。 | bǎ nǐ de chóumǎ fàng zài zhèlǐ. | Place your token here. |

| 把那张牌弃掉。 | 把那張牌棄掉。 | bǎ nà zhāng pái qìdiào. | Discard that card. |

| 请把色子递过来。 | 請把色子遞過來。 | qǐng bǎ shǎizi dì guòlái. | Please pass the dice. |

| 你同意吗? | 你同意嗎? | nǐ tóngyì ma? | Do you agree? |

| 你有木头、砖块等等吗? | 你有木頭、磚塊等等嗎? | nǐ yǒu mùtou, zhuānkuài děngděng ma? | Do you have any wood/brick/etc.? |

| 再掷一次。 | 再擲一次。 | zài zhì yī cì. | Roll again. |

| 你想交易资源吗? | 你想交易資源嗎? | nǐ xiǎng jiāoyì zīyuán ma? | Do you want to trade resources? |

| 洗一下牌。 | 洗一下牌。 | xǐ yíxià pái. | Shuffle the cards. |

| 那违反规则。 | 那違反規則。 | nà wéifǎn guīzé. | That’s against the rules. |

| 游戏现在结束。 | 遊戲現在結束。 | yóuxì xiànzài jiéshù. | The game ends now. |

| 我该怎么做? | 我該怎麼做? | wǒ gāi zěnme zuò? | How do I do this? |

| 你有多少分? | 你有多少分? | nǐ yǒu duōshǎo fēn? | How many points do you have? |

| 等一下,我还没准备好! | 等一下,我還沒準備好! | děng yíxià, wǒ hái méi zhǔnbèi hǎo! | Wait, I’m not ready! |

| 我需要掷色子。 | 我需要擲色子。 | wǒ xūyào zhì shǎizi. | I need to roll the dice. |

| 我们需要记录分数。 | 我們需要記錄分數。 | wǒmen xūyào jìlù fēnshù. | We need to keep track of points. |

| 过。 | 過。 | guò. | (I) pass. |

| 这个符号是什么意思? | 這個符號是什麼意思? | zhège fúhào shì shénme yìsi? | What does this symbol mean? |

| 我交换资源。 | 我交換資源。 | wǒ jiāohuàn zīyuán. | I’ll exchange resources. |

| 下一步做什么? | 下一步做什麼? | xià yībù zuò shénme? | What’s the next step? |

| 我出这张牌。 | 我出這張牌。 | wǒ chū zhè zhāng pái. | I’ll play this card. |

| 谁先开始? | 誰先開始? | shéi xiān kāishǐ? | Who goes first? |

| 我把这个留到之后。 | 我把這個留到之後。 | wǒ bǎ zhège liú dào zhīhòu. | I’m saving this for later. |

Editors note: This article, originally published in 2016, was rewritten from scratch and massively updated in February 2025.

7 comments

Great article! I love board games.

It would also be good to include at least a few games that you recommend and what level of Chinese would you need to play them ..

Great idea. Any suggestions on good board games? My first thought would be standard board games that happen to be in Chinese like Monopoly.

I played 卡卡頌 for the first time in Taiwan with the rules explained to me in Mandarin (though after the rules were explained, it’s not a game which requires much talking). It was only recently that I learned that the English name of the game is Carcassonne. The fact that I still remember it all these years later shows just how memorable the experience was.

Recently played “Guess Who?” in English with my friends from China’s daughter who is learning English. It was a great game for simple and repetitive conversations and I think I might buy the game for the Chinese language classroom.

Hello!

Love the article, thank you!

I think you can also mention some games that represent a communication challenge : such as Imagine (a kind of pictionary with transparent abstract figures), Codenames (you have to make others link different words based on a single clue), Spyfall (everyone knows where they are except the spy, all is in the questions the players ask).

三国杀 can be played freely online (mobile). Agricola (农场主) is available in Chinese. Dixit is one of the picture games which can be played in any language.

Yeah, I’ve played Dixit many times with Chinese people! Definitely some differences in how people associate and think.