As frequent readers will have noticed, I usually write articles about how to learn rather than what to learn, not because I don’t think what is not important, but because I think that others are already good at covering this.

As frequent readers will have noticed, I usually write articles about how to learn rather than what to learn, not because I don’t think what is not important, but because I think that others are already good at covering this.

That is not true for Mandarin pronunciation in general and the third tone in particular!

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many other platforms!

Learning the third tone in Mandarin Chinese

In this article, I will talk about the third tone. Based on ten years of teaching Chinese, with a particular focus on pronunciation, along with hundreds of hours of research into tone acquisition, it’s safe to say that the third tone is by far the most problematic tone for most learners, at least those coming from non-tonal languages, including English, Spanish, French, German and so on.

This is partly because the third tone is inherently more complex than the others, but also because the third tone is badly taught. In this article, I will explain the problem and what you can do about it, regardless if you’re a student or teacher of Mandarin.

The third tone in Mandarin: Basic facts

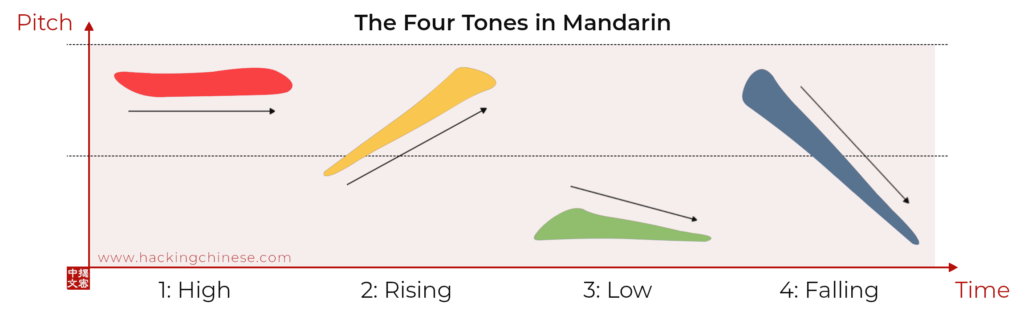

Just to make sure that everyone is on the same page, here is how the third tone is pronounced:

- Before a 1st, 2nd or 4th tone, the 3rd tone is pronounced as a low tone

- Before another 3rd tone, the first 3rd tone is changed into a rising tone

- In final position, the 3rd tone is often (but not always) a low tone

- In isolation, the 3rd tone is usually pronounced as a falling-rising tone

There is little controversy regarding this, with the possible exception of the third tone in final position, but research suggests that even well-educated native speakers with good pronunciation do not go up at the end, even when reading aloud. See Duanmu San’s The Phonology of Standard Chinese (2007) for example. Note that when I say “low”, I actually mean “mid-low to low”, which corresponds to the first half of a full third tone, usually called 前半上 in Chinese (上 is pronounced shǎng here and is a different name for the third tone).

The only related area where there is still serious debate is how to analyse many consecutive third tones (see Duanmu’s book again for a discussion of various approaches). That’s beyond the scope of this article, though, here we’re looking at the basics, but if you want a quick rule of thumb, breaking up a sentence into meaningful units (words, for example) and applying the above rules within words first, will yield decent results. However, rate of speech does influence the outcome, so the faster someone speaks, the more tone changes will occur.

The third tone is an essentially low tone

Of the above cases, the first is by far the most common, the others do appear, but much less frequently. This means that the third tone in Chinese is an essentially low tone. If you think of it as dipping tone, your pronunciation is likely to suffer (more about this later).

Here are some common two-syllable words that most learners get wrong. These are supposed to be pronounced with a low tone on the first syllable. You should never rise on the first syllable! You can listen to a native speaker from Beijing pronouncing each of the words by clicking on them.

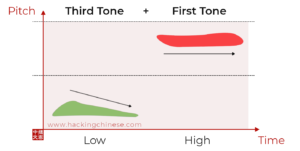

- Third tone + first tone (left), as in 老师 lǎoshī “teacher” or 北京 běijīng “Beijing”

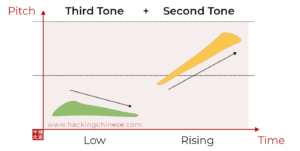

- Third tone + second tone (right), as in 可能 kěnéng “maybe” or 女儿 nǚ’ér “daughter”

This means that the only time a third tone is actually pronounced in a falling-rising manner is in isolation or sometimes at the end of an utterance (but this is optional; it’s normal to pronounce it as a low tone even at the end of sentences).

Now, if an alien read this article, it would probably assume that the third tone is described as a low tone to beginners. After all, if it’s almost always pronounced like that, so why make it much harder for learners by teaching it as a falling-rising tone?

Good question! The answer is that it’s taught as a falling-rising (dipping) tone for reasons of history and tradition; not because of what makes most sense when teaching foreigners.

Does it matter? What’s the big deal?

This might sound reasonable, but why do I make such a big fuss about it? Because it really is a big problem for many students. In fact, I hear more students who make this mistake than students who don’t!

Let’s look at the example words above again:

- 老师 lǎoshī “teacher”

- 北京 běijīng “Beijing”

Can you hear the low tone? The tone pattern here is supposed to be low + high. Do not rise on the first syllable!

Let’s look at the next pattern:

What about now? Still no rise on the first syllable. Keep it low! The most common student error is to go up on the first syllable in all these examples.

Another common example is 美国 měiguó ”USA”; I can’t even count the number of Americans I’ve met who pronounce the name of their country as méiguó!

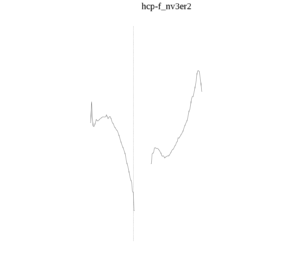

On the right, you can see what the pitch contour of a correct third tone plus second tone might look like in Praat (the dotted line is the boundary between syllables).

If you think of the third tone as a low tone, tone changes become easier

While pedagogy can’t get rid of the complexities of the spoken language itself, it can make them easier to approach. Compare teaching the third tone as a low tone with teaching it as a dipping tone when it comes to tone sandhi (tone change) rules:

Teaching the third tone as a low tone:

- No rule required in a large majority of cases

- When two appear in a row, change the first to a rising tone

- When in isolation, add a rise to the end

Teaching the third tone as a dipping tone:

- In a large majority of cases, change to a low tone

- When two appear in a row, change the first to a rising tone

- No rule required in isolation (quite rare in connected speech)

In the first case, we’re talking about applying some kind of rule maybe 20% of the time. In the second case, we’re talking about a applying tone sandhi maybe 80% of the time. If 80% of cases are exceptions, I think there’s something wrong with the rule. By considering the third tone to be a low tone, there are only 20% of cases that need special treatment.

How to fix issues with the third tone as a student

So, by now you should be aware of the problem, but unless you are very confident, do not trust your own listening ability here, because you might think that you’re doing it right, but in fact you’re not.

A good way to figure this out is to play tone bingo, where the listener simply can’t guess what you’re trying to say and have to be honest with you:

A smart method to discover problems with Mandarin sounds and tones

So, assuming you have this problem, what should you do? Here are some quick suggestions:

- Make sure you know how the tone is supposed to be pronounced (see above)

- Listen as much as you can and see if you can hear the difference (if not, then check Learning to hear the sounds and tones in Mandarin)

- Ask a native speaker to exaggerate the difference for you, then gradually returning to more normal pronunciation

- Mimic as much as you can: record, compare, ask for feedback; repeat (more details here)

- Learn one word to perfection for each tone combination, then use that as a model (see tone pairs)

- Check your pronunciation with native speakers regularly (such as tone bingo)

- Don’t give up! 千里之行,始于足下!

I know this is hard, because I’ve been through it myself. I had studied Mandarin for more than two years before someone alerted me to the fact that I was pronouncing the third tone wrong. I almost didn’t believe them at first. How could it be that the ten different teacher I’d had up until that point didn’t point this out? Of course, I did have a problem with the third tone. It took me a lot of effort to undo that, so part of my motivation for writing this article is to help you avoid the same problem!

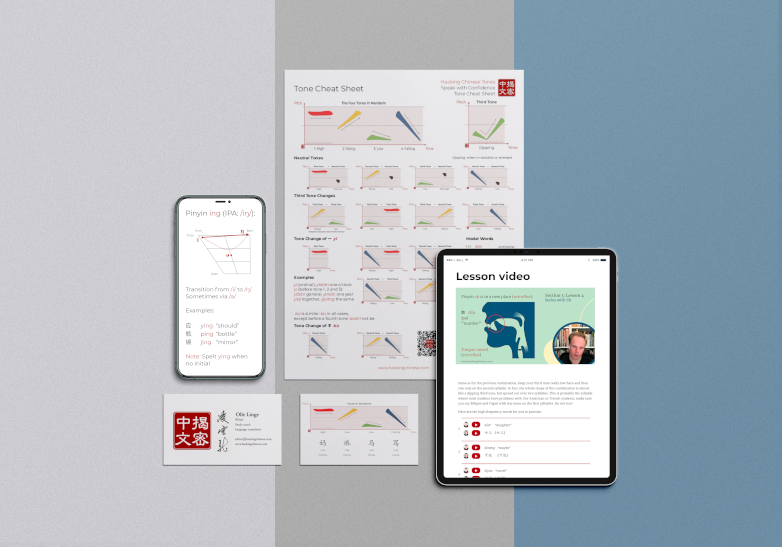

Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speak with Confidence

As should be clear by, I’ve spent a serious amount of time and energy on learning, teaching and researching Mandarin phonetics and how to learn and teach it effectively. I have put all of that into a comprehensive pronunciation course, covering everything you need to know about Mandarin pronunciation, including tones, initials, finals, prosody and also how to learn these things. Here’s the first episode, where I introduce the course:

The course is not always open for registration, but you can always sign up to the waiting list. I also announce when the course opens through my newsletter and on social media, so as long as you follow Hacking Chinese anywhere, you won’t miss it!

More about learning tones in Mandarin

You will sometimes hear people say that tones aren’t particularly important in Mandarin, and that the Chinese themselves don’t care that much; if you can just speak fluently and quickly, you will be okay.

This is wrong.

It’s true that tones aren’t always pronounced the way they are described in textbooks, but that is not an excuse to ignore tones when you learn Chinese. I have met people who really have completely ignored tones when learning and they have all bitterly regretted that, having to go back and relearn almost everything. I wrote about this problem more in Learning tones in Mandarin is not optional:

Now, if your goal is to make people who don’t speak Mandarin think that you speak the language well, speaking faster is a great idea, but it won’t fool anyone who actually understands the language. If you really want to learn to speak fluently and with clarity, focus on clarity first.

There is a huge difference between a native speaker being sloppy with pronunciation and a foreigner being sloppy. A native speaker is sloppy in a way that others are used to and that makes sense based on the phonology of the language. All native speakers do that and it’s very natural. However, most Chinese people are not used to your sloppy, rushed pronunciation. So: Learn by exaggerating: Slow, then fast; big, then small).

Finally, I think the reason some say that tones don’t matter is that they’ve spoken Chinese in an environment where the listener can guess what they are going to say. If you stand with all your luggage outside your hotel, looking very much like a foreign tourist, as long as you say roughly the right thing, the taxi driver will understand that you want to go to the airport.

Now try the same thing, but choose an obscure address the driver does not expect you to go to. It generally doesn’t work unless your pronunciation is spot on. Also try discussing or expressing something fairly complex using more advanced vocabulary, and you’ll find that wrong tones makes people unable to understand what you’re saying. Sometimes even a single mistake can make the listener not understand. I’ve written more about this in: The importance of tones is inversely proportional to the predictability of what you say:

The importance of tones is inversely proportional to the predictability of what you say

Further reading

This article was originally based on the bachelor thesis in Chinese I wrote in the spring of 2011, which still contains a lot of references for those who want to read more. However, since writing the thesis, I’ve taught Chinese for another ten years and also studied two years in a master’s degree program for teaching Chinese as a second language, so the below text is not really something I would be proud of today. Still, I haven’t written anything more up-to-date, so I’ll present it here anyway.

Here is the abstract, a link to the thesis itself is provided at the end:

The goal of this paper is to examine various representations of the third

tone in Standard Chinese, both in academic literature and textbooks for

beginners, and then evaluate what consequences the choice of

representation has for tone instruction. It was found that linguists primarily

prefer two models, even though slight deviations were found: either a

traditional approach describing the third tone as a falling-rising tone or a

model representing the third tone as an essentially low tone.A survey of fifteen textbooks showed that a huge majority used the

traditional (falling-rising) representation of the third tone; only one textbook

described the third tone as an essentially low tone. Except for this

discrepancy, tone instruction was found to be homogeneous across the

spectrum of textbooks analysed.After a careful discussion of the various flaws and merits of the two

different methods, it was found that considering the third tone as a low tone

would be beneficial for learners of Standard Chinese, mostly because it

conforms to the wide distribution of low pitch third tones in natural speech

and thus leads to easier rules for tone sandhi that need not be applied as

often as those applicable to traditional representation of the third tone.Finally, it is suggested that the third tone should be described as a low tone

for beginners, but that more empirical research is needed in this direction

to confirm the theoretical analysis. There is also much research left to be

done in the realm of practical tone instruction and how to best convey tones

to beginner students of Standard Chinese.

Teaching the Third Tone in Standard Chinese: Tone Representation in Textbooks and Its Consequences for Students (PDF, 464 KB)

Editor’s note: This article, originally from 2014, was rewritten (almost) from scratch in February 2021.

96 comments

I’ve heard about similar ideas about the third tone, but I’m not sure what to believe. My Chinese teacher in Finland (from Tianjin) sain to us many times how wrong it is to say ni2hao3 and it should be ni3hao3. Native speakers and teachers have different opinions on this, so what to do?

Even though I think tones are important in Chinese, I do have noticed that when speaking full sentences the tones aren’t as important as when saying an isolated word. At least it feels like that on this elementary level I’m on at the moment.

You gave some good tips to imporove pronunciation! I think a good way to practice is to listen to an recording and reading aloud after that. Also having a tutor was very helpful for me. I’m not sure about the 5th part though. I do read aloud slowlier when I’m practicing pronunciation, but when speaking with people I use more natural speed of speaking. I’m afraid that if I start speaking slowly and stressing everything very clearly, then I would just sound stupid.

p.s. I really like your blog and the how approach to learning Chinese. You are right, there aren’t really other blogs with the same idea!

@Sara

First, thanks for the kind words. I do my best to provide original content and even though I know that many people read the articles, it’s still very nice to hear you say that.

As for the third tone, there are some controversies, but not concerning what you say. I can say for sure that either you have misunderstood your teacher or your teacher is wrong. I’ve read hundreds of descriptions of third tone sandhi in articles and books. I have also been taught by at least ten different teachers. I have never encountered any suggestion that third tone change I suggested in the article is wrong. Feel free to check any of the sources I list in the thesis.

It is true that tones matter less on sentence level, mostly because a sentence gives the listener a context, making it easier to guess. This is true in any language and becomes even more true if you look at entire conversations.

Regarding the fifth suggestion, yes, you will sound stupid, but that’s okay. The goal of learning Chinese isn’t to sound smart while you learn (or so I hope). The rationale behind the suggestion to talk slowly is that it’s very easy indeed to speed things up, but extremely hard to slow things down if you’ve never learnt to pronounce things properly. However, you don’t need to speak slowly all the time, just do it sometimes!

The whole idea that something like tones are even “confusing” or are sometimes disagreed upon makes me sad.

Why would I want to risk learning a language where something so trivial like the tones are “controversial” or cannot be agreed upon by everyone?

Makes me scared to continue, it seems like Korean was a better choice 🙂

I may have worded some of that wrongly, but I think you will know what I mean.

It just scares me that I may be saying something wrong.

You will encounter misunderstandings or incompetent teachers in any language, that’s not reserved for Mandarin Chinese! There is no serious debate how the third tone is actually pronounced, the discussion is about how to teach it best. While I have encountered many inadequate descriptions of third tones in textbooks and teachers, very few have been factually wrong. So, in other words, I have never encountered a teacher like the one Sara tells us about. I think that’s very rare. Don’t worry! Make sure you get feedback from teachers and/or native speakers often and you’ll be fine.

The fact that something isn’t agreed upon just means it’s a matter of style, which, I would guess, is inherent in every language? Even if a language was enforced by law to be spoken in an exact manner, there would be people who spoke it differently over time (I’m “arm-chairing,” here.)

I guess my teacher was wrong then, because she said it very clearly. But how can a Chinese teacher who have been teaching Chinese for years not know it? Gets me thinking what else did she taught me that wasn’t quite correct.

To be honest, I have no idea. Perhaps she was referring to the way it’s written? I mean, you don’t actually change the third tone to a second tone, it’s just pronounced that way. You would still write two third tones.

Recently I’ve realized that there were lots of things my teacher didn’t teach us back in Finland.

And also I’ve had to change my opinion about the importance of tones. Natives seems to usually understand me pretty well, but that might be because thei guess or are used to Cantonese people pronuncing things wierdly (is that possible?).

The revelation came in a form of a fellow foreign student who has very good pronunciation and tones. He doesn’t understand if I say si1bai3 when I meatn 400 si4bai3.

I also got a confirmation by my teacher (when I asked her directly) that my tones are off.

I hope that those who are on the beginner levels will concentrate on the tones in the beginning so they don’t have to do as I’m doing, go back to the basics.

This is something I hesitate to write an artcicle about, simply because it’s mostly speculation, but I think that, somewhat paradoxically, tones become more important the more advanced your Chinese becomes. Let me use a very simple example.

Student A has a very limited vocabulary and asks for two beers in a bar. Any native will understand this, even if the tones are completely off. Actually, it might even work if he speaks in Russian.

Student B has a somewhat broader vocabulary and can talk about her family. Even if she misses some tones here and there, the native speaker can follow this because the conversation is easy to follow.

Student C is at a fairly advanced level and discusses and ethical problem and want to use a metaphor to explain his reasoning. If the tones are off, the native speaker will be confused. I personally find myself in ths situation now and then, thinking to myself (couldn’t you have guessed that, I just missed one tone?).

This is related to the predictability of what you’re saying. As it drops (as in the above examples), tones become more and more important. If your friend can guess what you’re going to say, tones aren’t very important, but if she can’t, then you they become very important indeed.

Take place names as an example. I’ve heard numerous stories of foreigners trying to give directions to taxi drivers with miserable results. Place names are very hard to predict, so tones are very important (except if you’re going where all foreigners are going, of course).

Oops, I think I just wrote another blog post. This might pop up again in a slightly modified format in the near future. 🙂

I’m studying Chinese for literacy, but I’m also an ABC who grew up in a Chinese household, and I have never heard ni3hao3, if that’s any help…

Now, just tell us how to say the fifth tone correctly, and we’ll be set. “No tone” my butt…what the heck does that mean?

I’m with you on hating textbooks. There is not a single good textbook for English speakers to learn Chinese. They’re all academic exercises, written by linguists to teach students of linguistics.

Textbooks are certainly not written by linguists. Linguists consistently give much better advice than the textbooks, for example on the third tone as discussed on this page. I do not understand how textbook authors can so constantly ignore linguists like San Duanmu and Yen-Hwei Lin.

@Harland

The fifth/neutral tone is different depending on the preceding tone. Basically, it falls somewhat after a first or second tone, goes up after a third and falls very low after a fourth. This picture might offer you some help: http://www.lenaia.com/images/pronunciation/pronunciationintroduction/tone1234neutral.gif

However, the real problem for learners regarding the neutral tone is when it should be used and when it shouldn’t, at least that’s what I find most difficult. Hope you find this useful!

Thank you!

I’ve been living in Taiwan for the past 3.5 years, and I don’t know if I’ve EVER heard the rising part of the 3rd tone (except, as you said, in an isolated word when someone is specifically explaining how to say it). And yet 99% of the learning materials I’ve read always start off with the full dip-and-rise 3rd tone.

It would make SO much more sense to teach the 3rd tone as low-falling, like you said.

@Stephen C

Actually, it is more common with a low tone in Taiwan than it is on the Mainland, especially in final position. However, the difference is not very big (i.e., most Mainland speakers also have a low tone in final position, it’s just more common in Taiwan). Creating teaching material that matches what is actually said should be helpful, both to improve students’ Chinese and their self-confidence (it’s quite annoying being told that something is pronounced in a a way which is usually isn’t).

Yes your teacher is wrong but this is common with natives speakers of ANY language, you often don’t know what you’re saying, you just naturally know what is right. Easiest thing is rather than listen to her explanation, get her to actually say 你好 and listen if the 你 becomes second tone – and you can be 100% sure it will!

That is right, and it reminds me of the time when one of my French friends asked a common Norwegian friend how to pronounce “hvordan går det?” (‘how is it going’). My friend, who is from Oslo, pronounced it without hesitation as [ˈʋûɾdɑn ˈɡòːɾ ˈdeː], which is as unnatural as two dipping tones in a row in Mandarin. What he normally says is [ˈʋûɖɑŋˈɡòːɖɛ], but because he was explaining it to a foreigner, he automatically switched to hyper-pedagogic foreigner-talk.

I agree, and this is why I think it’s not always a good idea to only rely on native teachers as a beginner. Some people can learn pronunciation just by listening to their teacher, but for those of us who need explanations, asking a foreigner who has reached a decent level might be a better idea. Native speakers will be very good at correcting mistakes and pronouncing correctly themselves, but don’t count on them being able to explain what they say, especially not in English!

I am a native Mandarin speaker and I am from Taiwan.

I (or we) have never learned “when two 3rd tone words together, the first word will change to 2nd tone” since day one.

Yes, when two 3rd tone words together, the first word “sounds like” a 2nd tone word. It will “sound like” a 2nd word natually; don’t need to memorize it or to emphasize this at all.

Make sure you always pronounce 3rd tone correctly, either in a slow speed or in a fast speed. See these two examples:

http://www.mymandarinchinese.com/mov/Ni3Hao3.m4v

http://mymandarinchinese.com/mov/Bu4Leng3.m4v

**That website is under construction.

Tracy

The third tone is still a third tone, of course, but it’s pronunciation changes to that of a second tone. It’s unclear whether the changed third tone is identical to a second tone or not, but it’s very close (same contour, but perhaps slightly lower). It’s easy for you as a native speaker to say that this comes naturally and that we don’t need to emphasise it, but this simply isn’t true for foreign learners. We need to learn this by having it explained, listen to it pronounced and practise ourselves.

Naturally, we should always try to pronounce all tones correctly. That goes without saying. I’m not sure what you mean by correctly here, though. I really don’t like the two examples you provided. No-one ever pronounces 你好 has two full third-tones, so I don’t think this is meaningful to practise. Instead, this might make students confused, because the teacher is saying one thing when speaking slowly and another whiles peaking at natural speed. If the teacher fails to explain this, some students will have problems. The third tone is mostly pronounced as low tone in Mandarin and this should be emphasised. Sometimes, before other third tones, it’s pronounced as a second tone. This needs to be explained as well.

*erm* I think you just solved all the problem(s) I ever had with Chinese in one blog entry (or one thesis, rather). So that’s why I never got it right when _trying_ and got it right when not thinking about it. *uhu* wow *_* thx orz

Glad to be of service! 🙂

Based on the textbook I’m using and information from teachers and on what I hear in the dialogue CD, I thought the half tone preceding a fourth was a half-tone rising, not falling. ie qing(3) jin(4) would be half tone up on qing and fourth on jin.

Also, one of my teachers explained to me once it’s not a full second or a full fourth tone in these cases, it’s always a half. So when it’s rising, it never goes as high as second and when it’s falling it starts kind of in the middle of a full fourth tone.

This helped my pronunciation enormously to think of it that way, and I am usually understood and told that my tones are unusually clear.

Read my text a little more closely and guess I misunderstood the teacher, but it is correct as you stated it, falling before a fourth tone. I noticed trying to read with this new thought in mind that it is going to be some work to undo this incorrect habit!

Thanks for this post. 🙂

Regarding the “half rising tone”, this is complicated. I’ve read numerous papers arguing that the rising tone resulting from two third tones in a row is identical to a normal second tone. However, I have also read papers which argue that there is a difference. The point is that if there is a difference, it’s very small and it’s not significant for ordinary students in most cases.

Like most students I learned early on that T3 becomes T2 if it precedes another T3. But I’m starting to wonder if that isn’t the same kind of myth as T3 always being falling-rising.

My current teacher has been much better than most natives at explaining tones, including teaching us about the low third tone, and other differences between prescriptive tones in dictionaries and such and the way natives actually speak.

While she has heard of the T3+T3=T2+T3 rule, she says that isn’t really true.

For example 你好 is much more likely to be pronounced as “low falling”+”traditional third” than as “second tone”+”traditional third” or “half rising”+”traditional third”.

This is also the way it sounds to my ears.

I wonder if you have heard anything similar and how much merit you think there is to this.

No, that pronunciation of 你好 would be really odd.

I somehow didn’t see Nuno’s comment befor Mp replied to it, but my answer would have been the same. I can, with considerably confidence, say that the teacher who said that the first syllable in 你好 is pronounced with a dipping tone is wrong.

I studied chinese for at least 4 years with different

chinese born teachers all of them teaching the “falling-rising” of the third tone. Also used Pimsleur that constantly talks about falling-rising. Then suddenly one non-chinese teacher fluent in chinese said “Oh, by the way, the 3rd tone is just a low tone – skip the rising part and it will be easier and you will sound more correct”. Thank you for letting me know after four years!!

I think part of the problem is that chinese-born people often try to teach “foreigners” the same way they were taught in a chinese way. Maybe the theory is that the 3rd tone is fallingrising but every one already speaking their mother’s chinese know how to pronounce it in daily speech. So they learn a theory in school

And teach us the same theory, but we have know other source

Thanks for this nice article. For a native speaker who is trying to teach Mandarin, your article gives me very good idea about how to explain things in English. Sometime it’s hard to put myself into the shoes of a foreigner who is learning Chinese. And it’s really important to stand in their place to find ways to solve problem.

The wrong description of the third tone might be very well one of the reasons i’m completely incapable of hearing any tone difference at all. I could do it in isolated cases but never in speach. It just was not consistent at all. (2 and 4 still sound exactly the same to me though.)

Thanks a lot, very helpful indeed!

I think, even though this approach might improve students’ pronunciation, it will also make it more difficult for students to attain a native-like level of pronunciation. Sun (1998) explains that telling students to always pronounce the third tone as low is a form of “putting the cart before the horse,” because full third tones do occur in every day speech. Lin (1985) outlines three instances where she observed full third tones in every day life. Anyways, I think there is a quite a bit of evidence that suggests that the best way to learn the Mandarin tones is through attentive listening and lots of practice.

I think very few people dispute that the best way of learning is through attentive listening and lots of practice. However, I fail to see why the fact that the third tone is indeed sometimes pronounced 214 would make much of a difference. The surface form is the same, it’s just a matter of how we get there. Describing what is true in 80-90% of cases and then describe the remaining exceptions (T3+T3 and stressed/full T3) makes much more sense than describing the exception and then going for the much more common form. In any case, I think it’s quite obvious that many teachers fail to emphasis on the lowness of T3, which means that many students incorrectly pronounces T3 as T2.

Thanks for replying.

Quick question, when you say low, do you mean half-third or you actually mean low as in it does not go down? (ie. similar to the first tone but just low).

I think it is unclear why a “low-third” tone will be easier for students. This method assumes students will be able to control their pitch in such a way that they will not confuse third and first tones. But if then can control their pitch that well, why not just pronounce the third tone the way it is supposed to be pronounced?

Describing T3 as 21 (low-falling) or 11 (low) is essentially the same. It’s very hard to to produce a low pitch directly, so if you tell people to produce a low tone, they more or less automatically produce a low-falling tone. Studies have shown that the difference between 21 and 11 isn’t very important, and since it makes it much more clearer to just say that it’s a low tone, that’s why I think it’s better than saying low-falling.

The arguments in the second paragraph are equally applicable to any kind of tone instruction. It’s all about pitch control. In the experiment I made with 40 students, T3/T1 confusion was almost unheard of, but that might be different for students of different nationalities. I think T3/T4 confusion is much more likely, to be honest, because we now have two tones that are actually falling in pitch. That’s why I stress the lowness rather than the falling. Still, this kind of confusion seems to be much less frequent than the T3/T2 confusion that is normally the case.

Lol, just had my first lesson with a native speaker today. Whenever I tried to say the third tone in combination with other sounds, he kept telling me over and over that I was making T2. Now I understand why…

Thanks for the post. Just started Pimsleur’s Mandarin I and was noticing this “disappearing” of tones. When the words are pronounced slowly, the 3rd tone is always heard as a dipping tone. When the third tone is part of a word or phrase, it seems that it disappears. Meiguo ren (american) or ni hao (hello).

It doesn’t disappear! It changes to a low tone in front of all other tones except another third tone, when it changes to a rising tone.

Thanks for this blog post. I’m sitting here after a couple of months teaching myself Chinese and I started to notice discrepancies in pronunciation in Skritter examples that couldn’t be explained by the “usual” descriptions of 3rd tone changes. This blog post cleared up my confusion really well.

It’s amazing how simple and clear-cut you’re able to present it here, while other, more traditional resources simply add to the confusion. Well done.

Your comment (and several others with a similar gist) gradually convince me that I should write some kind of pronunciation guide to Chinese, not because I’m really an expert compared to some people I know, but because most existing resources are so bad. Thanks for the thumbs up and good luck with your studying! 🙂

Thanks for the well wishing! Your post has really given me some food for thought since reading it, but it raised an important question that might be useful for a future pronunciation guide: what is defined by an “isolated character”?

For instance, is 我 in “我是” isolated? True, they’re two separate words, so you could argue that it should be pronounced with the full rising/falling tone, however it’s also immediately followed by a 4th tone, which might also have an effect on its pronunciation given the pronunciation changes you write about in this blog entry.

There’s probably a clear answer here, but for someone learning on his own, it could use some clarification.

Matti’s comment, “I think part of the problem is that [C]hinese-born people often try to teach “foreigners” the same way they were taught in a [C]hinese way”, hits the nail on the head: most learning materials are still under the shadow of the (inefficient) repetitive methods habitually practised in Chinese classrooms.

Proof of concept? Just listen to callers to radio phone-ins from places where languages other than Mandarin are used, and remember that all these people were schooled solely in Mandarin for years on end, yet some can only speak haltingly in Mandarin; presumably, many more avoid speaking it at all.

instead of thinking about graphics a use the lowest point of my voice, that “strong” intonation and the the beginning and the end of the syllables as a reference:

beginning end

no strong no strong – tone 1

strong no strong – tone 2

no strong strong – tone 3

strong strong – tone 4

With kind of back and white contrast I become able to hear and say the tones more intuitively, without pretending to make a question every time I want to say tone 2 (and without overemphasizing it like in a question). And really understand what’s going on on my vocal cords. I also feel that by touching my neck above my chin I can feel the differences in intonation with my touch.

This reminds me of a commentary that said that people overthink the difficult of tones, and I agree, getting them effortlessly at fast speech takes time but actually understanding them and producing tone pairs right while concentrating can be done fast. It just doesn’t happen that way because the material is bad or the learner don’t care.

This would be better explained in a video, but hopefully it’s clear. I wonder if other learners did something similar to this.

I think there are two reasons people have huge problems with tones and tones being super-difficulty isn’t one of them. The first is what you said, most people simply don’t care enough to correct their problems, especially if they feel that the problem is manageable. The second problem is that many people think that their tones are good or at least okay, but in my experience almost all students overestimate their own ability further reducing the perceived need to fix the tones. It would be interesting to do a study and see which of these are more common and if there are other reasons. Simply investigating how people’s perceived ability of their tones relates to their actual tone production would be a start, perhaps this has already been done?

I decided to run a mini-research based on Brett’s question. Here’s the results:

wo_zai

wo_zai_wan

shi_bu_shi_you

wo_lao_chu

In all cases 我 is a half-tone which just makes sense, why pronounce the full tone if we can just be lazy and say to low one? That’s more than laziness tough, Chinese is stress-timed, in this case she took only 0.11 seconds to say 我, she wouldn’t be able to make a falling-raising tone even if she wanted.

Also the other words, including the stressed ones, have flatter curves than those perfect isolated tones, the faster they are spoke the flatter is the tone, but most of them still curved enough to make the tone clear.

We don’t need to think to much to see that grammar-related, high frequency words are often unstressed, specially if the came after other words, it’s clear that 是不 and 是有 are pronounced like two words and the 不 and 有 becomes just a extension of the 是 tone.

I think that all ones need to do is keep trying to get the tones right in single words and when the time to make full sentences comes their stress and length will naturally starts to change the tones.

how to pronounce if more than 2 3rd tones come together followed by other tone.

我想买米饭。

There is no perfect method, but dividing it up into semantic (meaning-based9 units is a very good start. To start with, deal with words separately, so 我想买米饭 should be separated into at least two parts: 我想买 and 米饭. Change all T3 + T3 combinations within these groups to T2 + T3. If you speak quickly, all the first three characters could be T2.

Whao, I studied Mandarin now for a while and I just watched that video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3wV8B4bx1lM

She also is explaining the third tone as a low tone. And I really have never heard that before, so Google got me to this article.

So now, this feels just weird, that I have learned such a basic thing wrong the whole time. Basically I always learned it as a falling-rising tone. This also shows that the didactics of teaching Chinese is still at an early stage.

Same exact situation for me as for Felix. I found that video, looked up the third tone, and here I am. I think this article is excellent. I’m very much a beginner in Chinese, but I noticed the tones weren’t exactly as described in various lessons. So when I listened to this video, I was very curious indeed. I’ve studied a lot of other languages, and your article/site reflects a lot of what I’ve been thinking about learning languages. The importance of the “how.” The usefulness of exaggerating sounds first (and I tend to learn good pronunciation before most students do because I prioritize it). Xie xie for this!

Hi Olle,

Thanks for the great article. Could you address how to pronounce more than 2 third tones in a row, which can happen in a single word or a mix of one/two syllable words. I chuckled at Tracy’s comment “Yes, when two 3rd tone words together, the first word “sounds like” a 2nd tone word. It will “sound like” a 2nd word natually; don’t need to memorize it or to emphasize this at all.”

I don’t understand why 2+ syllable words starting with a series of 3rd tones like 展览,你好,左转 are ever taught as 3/3 since they are never, ever pronounced that way in normal speech. Why not TEACH nihao as 2/3, and zuozhuan as 2/3? I hope it’s not to try to get people to associate tones with characters, because that falls right apart with very common characters like 为,长,重, etc. It kind of drives me nuts. I think part of the reason tones are very poorly taught to non-native speakers is that native speakers don’t ever have to learn tones in school, they learn it growing up (or at least from the very first school year – I know there are some toneless dialects).

How are these combinations of 3rd tones pronounced?

3 word combo 我很喜欢

1 word 胆小鬼

2/1 combo 展览里

1/2 combo 我理想

I found your very very useful pages via twitter. Pronunciation and listening has always been a big problem and I’ve given up – several times. I study by myself, so I’ve mostly focused on reading (but not aloud). Last week I promised me one more try, this autumn I will learn how to speak Chinese. I feel it embarrassing because I have to go back to basics though I’ve made HSK5 two years ago! But it seems that there is no other way.

Thank you for all your advice you give on your pages, I have never seen anything like this before. Now I have installed Anki and Audacity and have started a serious work to reach my goal.

About the topic, I found an interesting book: Chinese pronunciation course: Peking University press, 2006. ISBN 978-7-301-07834-1. It has a figure of “real pronunciation of 4 tones”, exactly as you told it.

How about the 3rd tone before a 5th tone? I guess it should be falling-rising?

Not really, normally just low again. But since the following neutral tone is often high, the whole word gets a falling-rising contour.

Nice to see this discussion is still going. I was wondering if my own trick I came up with might eventually backfire or not: Have you ever noticed when you try lowering your voice as far as it goes that, the harder you try, the higher it rises again, unintentionally? I felt that speaking third tone words in this “faux-barritone” register might mean I would never have to concentrate on whether my voice rose again or not. In other words “if not then fine, if by accident no harm done”. Does it sound wrong, this concentration on a low register?

I’m not sure I understand exactly what you mean, but I assume you mean that your voice tends to rise higher afterwards if you first go lower, right? I haven’t noticed that myself, but the cases where you want it to rise at all are very few indeed. The only case where I would say it’s required is when you enunciate something for clarity, such as when announcing a number or when repeating something the listener missed and want you to clarify. Thus, aiming for a pure low tone is a much better starting point than anything else.

This has been so, so helpful. My god, why is the third tone taught wrong all across the world?! This is why people quit. This is why people get frustrated. This is why people hesitate to practice in a live setting. Irresponsible teachers who only know how to parrot a language book from 1980. There should be some sort of small revolution/reformation in the teaching of Mandarin tones. Thank you so much for the clarification, I think I’ll be getting back to practicing now!

In my opinion, that “v” shaped mark for the 3rd tone is misleading. I think it should be changed for another sign like an underscore (or just underlining the vowel) when the 3rd tone appears in a pair. I am a visual thinker so for me la̲oshī would make more sense than lǎoshī as in this case the 3rd tone is pronounced more like a flat low tone.

Yeah, a different tone mark would be preferred, although I think it might be confusing to place them beneath the vowel since no other tone marks are. I’ve sometimes seen something that looks like a rotated and flipped “L”, i.e. a short vertical stroke, followed by a longer horizontal stroke. Even if a satisfactory symbol was found, the chances of gaining widespread use is close to zero, I’m afraid!

Wow, this is so interesting. I have noticed for a bit now that something is weird with the third tone, but could not quite put my finger on it. Especially during the recent listening challenge. I was wondering why it was so much easier to identify third tones in single words rather than whole sentences. Now I have the answer – I have been listening for the down and up pattern, when really I should have listened for a low tone.

Exactly the same here!!

“There is little controversy regarding this”

No, no, no, no, no, no, a thousand times NO!

Find a single language textbook that supports this weird “low tone” idea. Start with the Beijing Language and Culture University Press. Particularly New Practical Chinese Reader, the standard textbook that foreigners learn from. You won’t find it anywhere.

So you’re saying you, Mr. Random Foreigner, knows how to teach Chinese better than Chinese people who speak the language natively, have certifications in Mandarin high enough to be a news reader, and have spent their entire lives furthering the teaching of Chinese? Come off it man. This is just some local Taiwanism that you’ve discovered and you falsely believe it to apply to all Chinese spoken everywhere. It’s no wonder, the way that mainlanders are looked down upon and those who use of simplified characters are considered deplorable. Why bother asking them? I wish you all the best in your ongoing battle with reality. Yours respectfully, a logical person.

I think you are maybe misunderstanding what I’m saying here, at least partly. The bit you quoted, i.e. “There is little controversy regarding this” refers to phonetic descriptions of the tones in basic words, and there really is no controversy here. Are you claiming that any of the rules right above the quote is not true? If so, which one? The only one that is up for discussion is the third one, which I also explain in the following paragraph. The others are certainly true, which is obvious to anyone who has spent time with acoustic phonetics.

I have never seen a phonetic/phonological description of Mandarin that claims otherwise. If you find one, that would be very interesting! When studying the sounds of a language, we look at phonetic/phonological analyses of the language, not textbooks for foreigners. I’m perfectly aware of the fact that almost no textbooks teach the third tone as a low tone, that’s even the conclusion of the analysis I did on a fairly large number of them. However, many of them do list these rules! Except the third one, as per my earlier statement.

So, the discussion here is not about how the tone is pronounced, but how it should be taught. Here, there’s obviously room for discussion and debate. However, I’m not sure that’s what you’re after, because the way you wrote your comment makes it look much more like an attack on me than a sensibly worded argument. The idea that native speakers somehow have automatic priority and are always right when teaching their own language is very strange. For example, I’m Swedish and I have no particular insights into how Swedish pronunciation is or should be taught. It seems rather pointless to discuss this if anything I say, whatever it is, is countered by “Mr. Random Foreigner”. Would it help if I said that the approach to teaching the third tone presented here was originally proposed by a native speaker of Mandarin? The first occurrence I know about is Dr. Liao’s presentation An Alternative Way to Teach Mandarin Tones in Speaking at the Chinese Language Teachers Association in 2008. I highly doubt that’s the first time anybody thought about it or wrote about it, but evaluating these ideas based on who came up with them first seems strange anyway.

Also, I’m not sure about where Taiwan comes into this. Why do you bring this up? What’s simplified characters got to do with it? Having spent a lot of time talking with people mainly from Beijing and various places in Taiwan, my personal observation is that the main difference when it comes to the third tone is that some in Taiwan pronounce the third tone as a low tone even in isolation, more so than people from Beijing. However, this is not part of this article as I don’t claim that the third tone in isolation is pronounced like that. I’m a bit confused by your attitude, could it be that you came here from somewhere else and maybe brought part of some other argument into the mix? I don’t know what I’ve done to deserve your comment, which was, frankly speaking, not respectful at all.

Find your novel third tone idea in New Practical Chinese Reader. I dare you. Or any other textbook. I await your citation by edition and page number.

But you won’t be doing that, because it’s not there. Who is more credible, J. Random Laowai or the Ph.Ds who made it their life’s work to teach Chinese as a foreign language?

望文生義

Like I said before, textbooks for foreigners is not where one would normally look for descriptions of tones, but if you insist, this is actually covered in New Practical Chinese Reader (I have the first edition, printed in 2003). The first rule I list (the one about the low tone) is covered at the top of page 32 and the second rule I list (about third tones in a row) is covered on page 9.

When it comes to the third tone, they say that it, “when followed by a first, second or fourth tone, or most neutral tone syllables, usually becomes a half third tone, that is, a tone that only falls but does not rise”. The traditional way of describing the pitch contour of the full third tone is 214 (1 being the lowest pitch, and 5 the highest, so 214 would be the dipping third tone), so the half third tone would be 21 (mid-low to low), which is often just called “low”, as I have done here. I’ve indicated the slight slope in the graph, as you can see.

For two third tones in a row, they say that the first “should be pronounced in the second tone”, or in other words, that it should rise.

Also, the description of the third tone I use in this article is neither novel nor mine, which I pointed out (with references) in the previous comment.

Thank you for this article. I have noticed this phenomenon myself, but thought I had heard it wrong. Even native Chinese teachers could not make this point clear! Now, my belief that Chinese pronunciation can be learned is back again!

Glad to be of service! 🙂