In a recent article, I discussed learning pronunciation in general and some important things related to writing down pronunciation in particular. In this article, I’m going to build on that foundation and discuss the merits of three commonly used transcription systems: Pinyin, Zhuyin and IPA.

In a recent article, I discussed learning pronunciation in general and some important things related to writing down pronunciation in particular. In this article, I’m going to build on that foundation and discuss the merits of three commonly used transcription systems: Pinyin, Zhuyin and IPA.

I think they all have their own merits and I know all three myself, so this article isn’t meant to be a competition where I crown the king of transcription systems, but rather a clear explanation of each and an encouragement for you to get to know them.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

Does it matter?

The transcription system you use probably won’t have a major impact on your pronunciation, simply because other factors are much more important, such as how much time you spend on pronunciation, how much help you get from a competent teacher, your attitude, which methods you use to practice and so on.

All research I have read about comparisons between Pinyin and Zhuyin are either inconclusive, methodologically flawed or show no significant difference between the two. If you have found any research that doesn’t fit this description, please let me know! I think there ought to be a small theoretical edge to Zhuyin if only accurate pronunciation is considered, but more about that later.

The point of this article is that even if most people can’t choose which system to use (it’s chosen for you by teachers and schools or where you study), you can still learn a lot about Mandarin pronunciation by learning an additional system, regardless of which one you started out with. Of course, there are many more systems than the three I talk about here, but these are the most commonly used.

Pīnyīn (汉语拼音/漢語拼音)

This is by far the most widely used transcription system for Mandarin and it’s also the most common system for teaching foreigners pronunciation. The system uses the Latin alphabet and was developed and implemented in the 1950s. I used Pinyin exclusively for the first year of learning Chinese, before I moved to Taiwan and learnt Zhuyin as well. Pīnyīn means “spelling sound”, which is what it’s for.

- Pros: The main advantage with Pinyin is that it’s widespread and used in most teaching materials, which means it’s easier to find resources for learning. Since it uses the Latin alphabet, it is also easier to remember how to write and therefore easier to learn (I’m talking about the symbols here). Another advantage is that you use a normal keyboard and if you can already type quickly, you can transfer that skill to typing Chinese as well.

- Cons: The major disadvantage with Pinyin is that if you’re not careful, you might fall into one of the many traps and pitfalls, meaning that you think something is pronounced in a certain way because of the spelling, but actually it’s not. If you learn the spelling rules properly, this is okay, but if you miss something, your pronunciation will suffer. Remember, learn the sounds before you learn to write them! Having letters familiar from your native language floating around in your head might also block you from hearing the real sounds. Don’t think that even simple letters like “t” and “d” are the same in all languages. Vowels are even worse.

Zhùyīn (注音符号/注音符號, ㄅㄆㄇㄈ)

Zhuyin has been around for a lot longer than Pinyin. It was introduced in the 1910s in China, but has only survived to any great extent on Taiwan. It is still the official transcription system there and widely used in educational material (including native children) and in input methods for computers and phones. I learnt Zhuyin during my second year of studying, but didn’t really use it unless required to. Zhuyin means “annotate sound” and Bopomofo are just the first four sounds in the system (which would be the same in Pinyin).

Pros: Zhuyin doesn’t have the disadvantages that Pinyin has since it doesn’t use the Latin alphabet. The symbols are instead arbitrary (from the learners point of view) and there is no interference from native language orthography. This also avoids another common issue with Pinyin, namely that it’s hard to avoid reading it if it’s on the page, thus ignoring the characters. Zhuyin is also more consistent in spelling of sounds, but still not perfect.

Cons: On the downside, Zhuyin doesn’t have the advantages Pinyin has either. First, it’s mostly used in Taiwan, so if you use it, it will be much harder to find learning materials. If you’re learning simplified characters, it’s almost impossible. Learning Zhuyin also takes longer because of the unique symbols you have to learn, although this is a reasonable trade-off considering that the sounds take much longer to learn than the symbols anyway. You also have to learn a new keyboard layout if you want to use it as an input method.

IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet)

When you write about spoken language in a scientific way, you have to be able to write down sounds accurately. Thus, the IPA, the International Phonetic Alphabet was created to work as phonetic notation for all the world’s languages. In IPA, one symbol stands for one sound and one sound only, which is the main difference between IPA and the other two systems here. It’s a system for phonetic notation, not a transcription for writing down the sounds of a single language. I learnt IPA for Mandarin many years after I started learning the language.

Pros: The main advantage is that the notation is much, much more accurate than Pinyin and Zhuyin. One sound one symbol, so you don’t need to remember the three different pronunciations of “i” or if there were supposed to be dots above “u” or not. Transcriptions in IPA can be in two forms, narrow and broad. Narrow transcription means that the representation is as accurate as possible, whereas broad transcription ignores many smaller nuances that make no difference in the language in question. Narrow transcription is usually too detailed for language learners, but can still be very interesting.

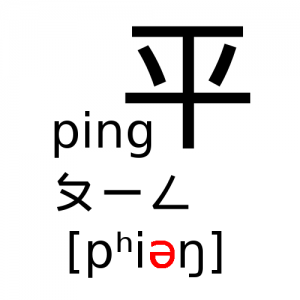

Cons: The obvious disadvantage is that IPA is harder to read and much harder to write: wu̯ɔ3 ɕi3xu̯an5 ɕy̯œ2 tʂʊŋ1wu̯ən2 doesn’t make much sense to most students or native speakers (it says “我喜欢学中文/我喜歡學中文”). Also, to benefit from using a system like this, you need to know what the letters mean. This is cool, because if you do, you can use them to learn other languages later! For instance, you will see that “zh” in Pinyin is not the same as the “j” in English “jump”, [tʂ] vs. [dʒ]. What does that mean? Well, that’s why you need to learn basic phonetics to make sense of IPA. I will talk about that more later. Still, even if you don’t know much about phonetics, seeing spelling in IPA can sometimes be helpful, such as seeing the [ə] in “ping”. In addition, IPA is really hard to type on a keyboard and almost no educational resources use it (Glossika is the only one I know of).

Converting between the systems

There are many tools for converting between the three systems, but I think this site is the most useful. It allows you to convert between all three systems, from simplified or traditional characters. If you know of other resources, please consider posting them on Hacking Chinese Resources.

Which system should you use?

As you can see, each system has its own merits. I use Pinyin because I can type characters much, much faster that way. I can already touch type with my keyboard layout (Dvorak), I don’t want to have to learn another layout just to write Chinese characters. If your keyboarding is lousy, though, learning a new layout can actually be a good opportunity to learn.

I also learnt Zhuyin after having studied Chinese for about a year. It was a big eye-opener for me since some syllables were written differently, which made me more aware of how Mandarin is pronounced. I don’t have personal experience of this, but I’m sure something similar would have happened if I had switched in the other direction, i.e. from Zhuyin to Pinyin (if you’ve actually done this, please share your experience with us).

When I started doing research into pronunciation, it became essential to master IPA, because that’s the only viable way of writing in academia and it’s also the only way to represent sounds accurately in writing. If you’re going to describe how students with different backgrounds pronounce the same syllable, you can’t use either Pinyin or Zhuyin, they only work for exactly the syllables they are meant to represent. When I learnt IPA for Mandarin properly, I had several eye-openers as well, figuring out many things that I had been only vaguely aware of before.

Conclusion

Don’t use just Pinyin or just Zhuyin to learn Mandarin pronunciation. You can of course use only one of them for everyday typing once you know the language, that matters little, but if pronunciation is your goal, you should learn more than one system. Of course, you should try to understand one of them before you try the others, I think learning both in parallel is overkill and will take too much focus from actual listening and pronunciation practice. Since which system you choose is mostly decided by your teacher and course, my advice is simple: learn the other system as soon as you feel comfortable with the first.

If you are really interested in pronunciation, though, nothing beats IPA. It’s when you understand accurate descriptions of Mandarin pronunciation that you really start understanding how it all works. Children can pick this up automatically, but adults often cannot. For us, understanding is essential. IPA shows you in writing what your ears may fail to hear. This is no guarantee that you will be able to sound exactly like a native speaker, but gaining a good understanding of your voice, how it works and how the sounds of Mandarin are written with IPA is of great help. This is covered in the next article in this series:

https://www.hackingchinese.com/learning-to-pronounce-mandarin-with-pinyin-zhuyin-and-ipa-part-3/

4 comments

Man, I freakin’ hate IPA. Talk about a user-hostile experience. I understand what it’s for, but unfortunately too many learning materials use it. Why? Because it’s what professional linguists use, and they either don’t know or don’t care that everyone else finds it incomprehensible. Yet another one of my flaming hatreds for look-down-their-noses academic linguists who make learning Chinese much harder than it ever needed to be.

What learning materials are using IPA for Chinese? I know of only Glossika, which might me “too many” if you really, really hate it, but I’m still curious which other books are using it. 🙂

If your comment was for English language teaching, I agree. I was also force-fed IPA without understanding it when I learnt English. It didn’t help at all and I remember nothing of it from that time. I only started liking it when I studied phonetics at university and had a brilliant professor.

Shouldn’t a link to the third article be present at the end of this one?

Yes, there should be! It’s sometimes easy to forget to update things like this, so thank you so much for pointing it out! I’ve added a link now.