Reading aloud in Chinese is really hard, much harder than reading aloud in most other languages. Ever since exploring this topic in a recent article, I’ve been thinking about reading aloud in Chinese and what factors are involved. In particular, I want to know why I’m not good at it and what to do about it. The goal with this article isn’t merely to discuss reading aloud, though; I also want to show how I tackle weaknesses in my language ability. I also want to show that even though reading aloud is hard, it’s not impossible.

A brief summary: Why reading aloud in Chinese is hard

A brief summary: Why reading aloud in Chinese is hard

In the article referred to above, I said that what makes reading aloud in Chinese extra difficult is that Chinese characters might have clues about pronunciation, but they’re not phonetic. When reading silently, we just need to be able to recognise the characters and associate them with meaning, but when reading aloud, we also need to retrieve the correct pronunciation from memory and we need to do it quickly.

To add insult to injury, there is no such thing as word spacing in Chinese, which further increases the cognitive load. Finally, since Chinese is an analytic language, a significant share of the communicative burden lies on the reader, who needs to decipher ambiguities and use context to determine the meanings of words and clauses.

I also summarised the skill components needed to read aloud in Chinese as follows:

- Map characters to meaning (character recognition)

- Group characters into meaningful words (vocabulary)

- Group words into meaningful sentences (grammar)

- Understand the meaning of sentences in context (pragmatics)

- Understand the writer’s intent (reading between the lines)

- Map characters to pronunciation (pronunciation recall)

- Understand how the pronunciation syllables influences each other

- Understand how meaning influences pronunciation (intonation, sentence stress)

What am I lacking? Why am I not better at X?

This is the basic process I go through whenever I encounter a language learning problem:

- Identify and describe the symptoms

- Find out what I need to be able to do to achieve X

- Find out which part is the weakest link

- Practise that component and see if it helps

- If it doesn’t, there’s probably a mistake in step 1-3

So, let’s do this for reading aloud. I have dealt with step one and two already, so let’s move on. Looking at the above list of skills, I can exclude a number of factors immediately. The first five can’t be the reason why I’m bad at reading aloud, because I can read silently about twice as fast as I can read aloud (~250 characters/minute for relaxed material). This means that getting the meaning of a text is not the problem. The three remaining factors are more interesting, though.

To test this, I decided to dramatically increase the amount of Chinese I read aloud, to try to figure out not only which the limiting factor is, but also if there might be more to it than this. I had the nagging feeling that reading aloud is a skill in itself, so even if I had all the components above, I might still not be good at it.

The experiment: Reading a novel aloud

To test this hypothesis, I decided to read an entire novel aloud in Chinese and time each chapter. Rate of speech is not a very good measurement of one’s ability to read aloud, because quality is definitely more important than raw speed, but since I was the only test subject, I could be quite sure that most other variables were kept constant during the experiment. For instance, my comprehension of the novel stayed roughly the same throughout the entire text and I’m quite sure pronunciation quality didn’t deteriorate, but might have increased somewhat.

I selected a novel I thought would be relatively easy without being childish (I didn’t want to have too many cases where my reading was actually limited by poor character recognition, for instance). For reasons not connected to the experiment, I chose the Chinese translation of Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games (飢餓遊戲). If you haven’t read the Chinese version, I can tell you that it’s slightly easier than other translated works of fantasy that I have read, but not by much, it still contains a fair amount of flowery language and idioms, but it’s not a difficult read in any case.

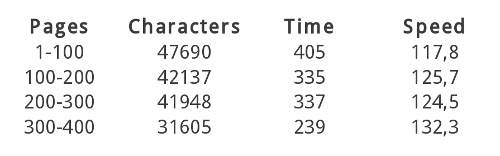

Here are some statistics for characters used in the novel, which of course doesn’t give a complete picture, but should still give you an idea (the numbers are calculated for comparable lengths of each book):

- Unique characters in 飢餓遊戲: 2800

- Unique characters in Twilight: 2600

- Unique characters in 醜陋的中國人: 3000

- Unique characters in the Bible: 3000

In case you want to count unique characters in electronic texts, I suggest using DimSum:

The question: Which factors influenced my performance?

The question I asked myself was what factors were slowing me down. Based on the list above, I identified four potential problem areas. As we shall see, most of them turned out to be irrelevant or of marginal importance.

- Character recognition (which is the first half of factor #6 above) can be ignored because the number of characters I didn’t recognise in the novel were fairly evenly spread out and were far and few between (no more than 100 in the entire book). This factor was clearly not interfering significantly with fluency and even though I learnt a few new characters, that certainly didn’t improve reading fluency in any measurable way. it might have saved a few seconds here and there.

- Character pronunciation recall time (which is the other half of factor #6 above) was more important, because even though I knew almost all characters, I sometimes found it hard to recall their pronunciation quickly enough. This was typically not a question of whether or not I could recall the pronunciation, but rather how long it took to do it. A delay of a second or more is quite noticeable on the rate of speech. Even though the recall rate should have dropped a bit throughout the novel (familiar objects, locations and so on), there are so many characters than I doubt that my overall recall speed increased at all during the experiment.

- Understand how the pronunciation of one syllable influences other syllables (#7 in the list above) would be a factor if someone never read anything aloud. When you read silently, you don’t have to parse several consecutive third tones, you don’t have to worry about tone changes for 不, 一 and so on. However, I have read a fair bit aloud in Chinese before and since I know I get this right most of the time in speaking, I don’ think it’s a major factor in this case. Still, my ability to do this quickly might have increased throughout the experiment.

- Understand how meaning influences pronunciation (#8 in the list above) was largely ignored in this experiment. I simply can’t parse the text quickly enough to figure out where the sentence stress should fall or how the type of sentence should influence pronunciation. I simply focused on reading the sentence correctly. This is a factor which is beyond being able to read aloud in a fluent manner and is closer to being able to read aloud well compared with native speakers.

The result: Reading speed might be a separate skill

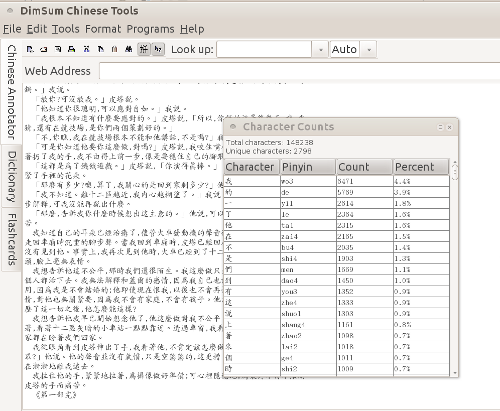

I spent 1316 minutes (about 22 hours) reading 163380 characters. This is what reading speed looked like across the length of the novel, measured in characters per minute:

As we can see, there is an expected increase in reading speed between the first two parts, which is easily explained by the fact that I got used to the characters in the novel, some setting-specific words and the author’s style. As we can also see, the speed didn’t increase much from page 100 to page 300.

As we can see, there is an expected increase in reading speed between the first two parts, which is easily explained by the fact that I got used to the characters in the novel, some setting-specific words and the author’s style. As we can also see, the speed didn’t increase much from page 100 to page 300.

But then something interesting happened.I started feeling that I could look ahead much more than before and that speed crept up quite a bit. Thus, the increase towards the end was definitely noticeable subjectively and actually didn’t flatten out towards the end of the book (the final chapter had an average speed of 145).

Even though the skill factors listed above did improve during the experiment, I don’t think the they are enough to explain the ~12% increase in reading speed. This is further supported by the subjective feeling that reading page 300-400 was qualitatively different from reading page 200-300.

Conclusion

Reading aloud in Chinese is hard, but apart from reinforcing the separate components, reading aloud itself is also a skill. By reading aloud, you increase your ability to pronounce words and, while doing so, looking ahead at the subsequent few words, as well as the ability to anticipate tone sandhi problems.

Your ability to read aloud in a fluent manner depends largely how much processing capacity you have left over to focus on something other than what you’re currently saying and I believe that this split attention can and should be practised, at least if you want to be able tor read aloud in Chinese.

However, that being said, I think most people have more fundamental problems than that. Based on personal experience, I think most students are unable to read aloud fluently simply because they either don’t know enough characters/words or can’t remember the pronunciation quickly enough. Still, if you’re reasonably good at reading silently, but is struggling with reading aloud, remember that reading aloud is in itself a skill you need to practise!

24 comments

While I agree that some of the components are specific to Chinese, I would say that reading aloud is a skill that needs to be practised to be good even in your own native language. i think most native English speakers are not that good at reading out loud. Sure, if they are highly literate, they can generally understand what they are reading and get the phonetics mostly right – but it will still sound very unnatural unless the reader has a lot of practice with reading out loud.

One factor you leave out – and which is actually pretty important for reading aloud – is breath control. You have to breathe once in a while, and when you breathe, you pause. To read aloud well, you have to train yourself to breathe at the ‘natural’ pauses. This can be inhibited by lacking in skill number 3, but it can also be inhibited by poor breath control (I’ve seen this happen with native English speakers reading aloud in English, and I’m pretty sure it’s not because they were lacking in component #3). If you have to read slowly because of low Chinese skill, that makes breathe control trickier (you can get fewer works said in one breath, which means your breaths need to be more frequent, which makes it harder to breath at natural pauses). Of course, how much breath you needs varies widely – it depends on volume (speaking louder requires more breath), your lung capacity, what types of breathing you’re doing (are you taking full deep breathes – which require longer pauses but means you can go longer before your next breath – or quick tip-up breaths which can be done much more quickly but also mean you need to breath more frequently).

There’s more to the skill of reading aloud than that … but I think I’ve made my point.

Perhaps this differs between individuals, but I have never found breathing to be a problem in any language. Sure, if we’re talking about reading well and being professional, but not if we’re talking about reading smoothly and correctly. In this particular novel, it wasn’t a big problem because I could usually read one sentence per breath, which eliminates the need to think about when to breath (full stop = breath). I imagine this would be harder for texts that only occasionally use full stops, though, but I still think this is discussing rather fine details between reading well and reading really well. I’m talking about a foreign language here, not reading in your native language, which is bound to have much, much higher requirements and standards.

Regarding breathing… it is related to pace.

If you are going to study or teach via reading aloud, the student should create a pace that is neither too slow or too fast.

Too slow is simply detrimental to progress. But the same goes for too fast as it is easy to hide mistakes and to presume the listener will figure out what is what. (So some students just read fast to seek less critisism from their teacher). If you construct a scale of crawl, walk, and run.. speach should be a leisurely walk so that all the pronunciation is present and yet the pace allows one to breathe. It is certainly not the pace you hear in a TV news broadcast in Chinese.

To get in touch with reality, I try to watch Chinese subtitled cartoons and to listen to what is said. Cartoons are geared for kids, so the vocabulary is more available to 2nd language learners and the animation provides the context to help recognize vocabulary.

But even in cartoons, you will find some phrases where the phonology of certain characters drops out. The same thing is present in Jackie Chan movies. Native Chinese do imagine that they say each and every character, the textbooks seem to assert that claim as well, but there are dropouts. So I am not sure that perfect character for character reading is teaching the student what to expect in the real world.

I think your ability to read aloud well in your own language is directly related to being able to read aloud well in a foreign language. If you do it very poorly in your own language, you probably aren’t going to do it well in another language. In fact, if you can’t do this well in your own language, you should probably practice getting at least proficient at it in your own language before working on it in your target language.

This is to be expected if reading aloud has a separate skill component. Being able to see things further down the line and some other tricks ought to transfer from one language to another. Obviously, if more basic problems exist, this won’t help, it doesn’t matter how good you are at reading ahead if you don’t know how to pronounce the characters, for instance, but that doesn’t make sense. Still, I’m reasonably okay at reading aloud in Swedish and English, so that shouldn’t be the main limiting factor for me personally. In other words, there’s more to it than that (I don’t mean to say you claim that this is the only factor, of course).

Very interesting article. I was especially struck by the fact that you read (silently) without recalling the pronunciation. When I read, I cannot help but recall the pronunciation – if I can’t recall it, I have to force myself to go to the next word, and maybe guess the correct word (in terms of pronunciation) before from the context. Only if I’m able to pronounce the sentence in my head I feel like I understood it.

Also, as a physicist, I wouldn’t fit that polynomial curve to these four data points. There’s just not enough data in the plot to do that. Just fit a straight line and call it a linear increase.

Stopping subvocalising is the key to reading speed in any language, but it’s not that easy to do. Some people recommend keeping the phonological loop busy by saying nonsense syllables aloud when reading, but I’ve found that I can do that and still hear the sound of the characters in my head. Still, trying to read faster than you are capable of is the key to achieving this. And about the graph, it just happens to look polynomial, whereas in fact it just has the edges smoothed out. I know this isn’t strictly accurate and will replace it if I can only find the original document. 🙂

My observations and students’ feedback have indicated that some learners of Chinese read texts without connecting to the sounds of the characters and some do. Some of my students (more visual ones?) read and understand the meaning but have trouble remembering the pronunciation of the characters. Some have trouble recognizing and/or writing characters but if I reverse the skills, say, give them the English meaning of the sentence or paragraph, they can say it in Chinese with relative ease. I think Chinese is unique in this regard.

Well, reading aloud in Chinese is indeed certainly different. But the focal points remain similar.. tempo, phrasing, and emphasis.

Trying to read characters without phonology indicated along side is a huge burden and I doubt that it is worthwhile for most. It might even be best to begin with all phonological representations of Chinese and skip the characters completelely. That is where Yale University and the U.S. Government started with teaching Chinese to American’s representing the USA in Chinese.

But even then, accent differs by location. Moving 100 miles can get a bit different phonology. And Taiwan is certainly different that Beijing standards. It is almost like comparing a Boston accent to one from Atlanta, Georgia.

I have mentioned before that the educators seem to present phonology over three to six months, whereas first language children develop their ability over 5 or more years. Expecting too much too soon can be frustration.

And since I live in Southern Taiwan, talking with a Beijing accent is rather absurd. People react as if I am a Martian.

So to begin with, embrace the accent that is most useful to you personally and don’t try to build phonology from tapes and CDs that have you talking like you are from somewhere else. I have a big library of tapes that are all Beijing accent and I set them aside 15 years ago.

The original material and tapes for the US government available free online as the US Constitution requires all government publications to NOT be copywritten. It is a great resource, but when in doubt… try to adapt pronunciation to fit in with your local community. You will get a lot more real interaction and progress.

An accept that you need to spend time every year on pronunciation review.. for at least the first 10 years.

I agree with the comment that like most or all skills related to foreign language learning, if you do it well in your L1, you will tend to do it well n you L2.

For myself, it has never occurred to me that reading aloud in Chinese is unusually difficult. On the contrary, my pronunciation when reading aloud is far better than in other speaking situations. It surprises me that this is not common experience.

My daughter likes her Chinese kids books more than those in her English collection and is happy for me to read them to her every night. I will ask her if she minds that Daddy’s reads so slowly. She always says she doesn’t mind which is a nice stroke of my ego 🙂

In fact this night time reading has appeared to increase my silent reading speed, though hasn’t had much of an impact on my vocabulary as you might expect. The words that are new to me in children’s books I dare say are not especially useful for normal communication and I tend not to retain them well.

I think most people have serious problems when reading aloud in Chinese, so your case is not typical. It would be interesting to know more about your case. Provided that you read correctly (correct tones, correct sounds, but not necessarily good intonation and so on), how fast do you read when you read aloud? How fast do you read silently? I know these will be very rough estimates, but it would be interesting to see what you have done to avoid something (almost) everybody else thinks is really hard.

Hi Olle,

I did a quick sampling as you suggested and here’s what I got:

reading aloud: 87 chars per minute

reading silently: 125 chars per minute

I recorded the aloud portion so I could truly see if it sounded ‘good’. I wasn’t displeased with it. The tones sound correct, though there were probably occasional errors with tones or a final or two. If I were to do a rereading of it, the flow and intonation would improve significantly from the ‘cold’ one.

I did not try to rush the aloud part at all, and just went at what was a comfortable pace for me.

Again, I don’t find it so difficult, but rather enjoy it. I don’t know what my speed says about this, if it is slower than expected or not. I’m happy to know what you think with this data in hand!

After posting, I looked up carefully at your own numbers. It’s interesting that the 125 mark seems perhaps significant, if not a coincidence, seeing that you leveled off there, too, before your jump.

I should note that I did this sample with a book (non-fiction) whose vocabulary range I am already practiced with.

Thanks for posting your data! The thing is that speed is the major factor that makes reading aloud in Chinese difficult. To give you an idea of what’s consider fairly slow and clear speech when reading a short article for instance, this article is read at about 225 characters per minute and to my ears, the reading is very slow. News broadcasts are much faster still. So, the thing is that I’m struggling with reaching 70% of this speed. If you read at 87 characters per minute, you’re not even up to 40% of the speed.

So, my guess is the reason that you think that it’s not hard is because you read too slowly. The extreme case would be reading one character every two seconds or so, which would obviously be very, very easy. Perhaps I should have said “reading Chinese at a reasonable pace is very hard”! Try and see what happens if you try to increase speed a bit, I think you will find that it becomes much harder very quickly.

I hope you don’t perceive my comment as overly critical of your Chinese ability, I simply want to highlight the fact that the speed factor is a crucial factor for the difficulty of the task. I’m not able to read aloud at anywhere near the target, which would be something like the article I linked to above (i.e. 225 CPM). Obviously, this is still much slower than most native speakers are capable of, but it’s a reasonable goal, I think!

Hi Olle,

I’m curious if you understood the novel as well as if you had read it silently, and if that might be another way that reading aloud in Chinese is different from other (foreign for the reader) languages. I’ve taught English quite a bit, and I’ve noticed that students don’t understand a text if they have to read it aloud before reading it silently, even if they are reading a text that is easy for them to understand if read silently. It seems they focus so much on pronouncing everything correctly and sounding out the word that they don’t really process what it all means. It seems that might happen less in Chinese simply because it is sometimes easier to remember the meaning of a character than its pronunciation, whereas in a language like English it is easier to figure out the pronunciation of the word than its meaning.

Thanks for writing such an interesting blog!

Emily

The phenomenon you describe is in fact very common when Chinese is taught as a second language. I know the problem exists in other languages as well, but it’s even worse in Chinese, because you can actually (in theory) be able to read a text without having the slightest clue what it’s about (if you’re really good at recognising characters but lack words/grammar, for instance).

To answer your question, if I would have spent as much time reading it normally as I would reading it aloud, I would obviously have understood it better. As I mentioned, my normal reading speed for this kind of text is roughly twice as fast, so slowing down means more time to think. It’s also quite clear that removing one aspect of reading should leave more processing capacity to other areas.

Competency at reading aloud is a skill mastered only with perhaps several hundred hours of practice (whether in or out of class). Court Reporting students are one class of professionals who spend hundreds and hundreds of hours reading aloud from their own tape-code (which is English rendered as CODE). Toastmasters is a group that encourages “out loud” reading and speaking. The point is that there aren’t any easy, stress-free ways of reaching the point where your speaking will sound natural and professional. You practice until you get it! If hundreds of hours are required, so be it. Far too many people simply lack the necessary discipline, motivation, resolve. Remember the Greek Demosthenes, who used to talk with pebbles in his mouth and recited verses while running. To strengthen his voice, he spoke on the seashore over the roar of the waves. (My note: There’s no such thing as too much practice. Old Japanese saying: 10,000 times I practice, I’m still a beginner.)

Another aside: I’ve learnt and am learning quite a bit from observing professional Chinese newcasters on various CCTV sites, and BonTV. Observing means using my eyes and ears to the utmost. The spaces between the words are as important as the words themselves. The newscasters’ eye movements say volumes on their processing of the material from which they’re reading. Also, I’ve found listening to ChinesePod QingWen Media audio extremely helpful in relating to the flow of words; as well, the radio broadcasters on Chinese radio stations are a study in reading aloud. Just listening while feeling how my body responds to the sounds is highly informative. Is this how babies feel while learning their Mother Tongue?

I find it difficult to read texts aloud to a class without stopping on a word… I think an a article based on finding a phonetic hint within components such as radicals might be helpful in cases such as mine.

Such as these two, perhaps? 🙂

Phonetic components, part 2: Hacking Chinese characters

Phonetic components, part 1: The key to 80% of all Chinese characters

As Chinese, i will say reading Chinese aloud is hard. In my junior high Literature class, we often did 阅读接龙.When ever a student made a mistake he/she must sit down and next one continued reading. Some people even couldn’t read a paragraph. But I was good at it. My record was 2 pages.

Reading Chinese is different from reading English. When reading Chinese, you have to map the whole sentence into your brain and then read it out. In English it is pretty much word by word, phrase by phrase.