Many people who don’t study the language think of Chinese as being a language much like English, with some variety but still mutually intelligible dialects. To most people, that’s what a dialect is: a way of speaking a language particular to a a region or group of people.

Many people who don’t study the language think of Chinese as being a language much like English, with some variety but still mutually intelligible dialects. To most people, that’s what a dialect is: a way of speaking a language particular to a a region or group of people.

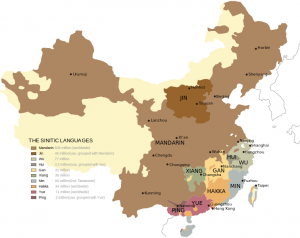

Linguistically speaking, it’s hard to draw a line between dialect and language, and Chinese is a good example of this. Many Chinese dialects are mutually unintelligible, meaning that two speakers from different dialects might not understand each other (see Tang & van Heuven, 2009, for a quantitative analysis of this).

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many other platforms!

At the same time, Norwegian and Swedish are typically treated as two separate languages, even though I can understand a lot in Norwegian based only on my proficiency in Swedish. As Max Weinreich famously said (or at least popularised): “A language is a dialect with an army and a navy.” So what you choose to call something is more about politics that linguistics, in other words.

For Chinese specifically, Victor Mair popularised the word “topolect” to correspond to 方言 (fāngyán in Mandarin). I will use this word throughout this article, which is actually not about dial… I mean topolects. Instead, we’re going to talk about how these other lang… topolects influence how people speak Mandarin in particular.

Understanding regionally accented Mandarin

According to 新华 (Xīnhuá), a state-run news agency, 73 % of the Chinese population spoke some form of Standard Chinese (普通话, Pǔtōnghuà) in 2015. This does not mean that they all speak it as their first language, though, as it’s very common to speak another topolect at home and learn Mandarin through education, mainstream media and so on. Regardless where in China you are, most people you encounter will not speak Mandarin with the standard accent you’re used to from your teacher or textbook recordings.

Indeed, this is true for native speakers of Mandarin as well, as the official standard is not the same as the Beijing dialect, although they do overlap to a large extent. In general, people will not speak perfectly standard Mandarin unless they have trained specifically to do so, and it is required for teachers, news broadcasters and so on.

This means that real people you talk to in China will bring bits and pieces of their native tongue into their Mandarin, or will speak it with a regional flavour. At first, this looks like a daunting challenge for learners, because even slight differences in sounds might make you unable to understand anything. Anyone who has arrived in a new place with a new accent will surely know what I’m talking about!

I remember a few confused situations, all taking place during my first year in Taiwan, but the examples I bring up here are relevant for speakers of many southern topolects in general.

Tea, happiness and familial bliss?

I was out walking late at night and wanted to have some green milk tea. None of the stands selling tea were open, so I headed over to a convenience store. I found my preferred brand of milk tea, placed the carton on the counter and handed over the money. I was about to turn around and leave when the clerk suddenly asked:

Yào jiā lè ma?

My brain couldn’t parse this. I shook my head in confusion. The guy looked at me compassionately and said it again, more slowly this time. He could probably see the vocabulary lists scrolling in my brain. Do you want to add happiness? Do you want a happy home?

No, sorry, I don’t understand.

Then, eureka! He was asking:

Yào jiā rè ma? (要加热吗/要加熱嗎)

So if I wanted him to heat the tea for me! Of course. In hindsight, that’s so obvious it baffles me that I didn’t understand what he said the first time (or even the second time).

He just pronounced /r/ as /l/. Beginner mistake on my part, I should have figured this one out, but I didn’t.

There is no něng. Or is there?

The next example left me even more perplexed. It happened at around the same time as the previous example while I was waiting for the bus with a friend, and she asked me:

Nǐ bú huì něng ma?

This particular friend usually speaks very good Chinese (or at least, I’ve heard other people say so), so I didn’t expect anything fishy. But still, I was pretty sure that there is no něng syllable in Mandarin, or if there is, I definitely didn’t know any word with that pronunciation.

She repeated the question several times, but it was only when she hugged herself as if freezing that I realised that she was asking me if I was feeling cold or not:

Nǐ bú huì lěng ma? (你不会冷吗/你不會冷嗎)

This time, /l/ had turned into /n/. Albert Wolfe shares an even better example of this, mixing up nǐ and lǐ in sòng lǐ (送礼/送禮, give a gift) vs. sòng nǐ (送你, give to you (for free)).

How’s your humu these days?

The third and last example comes from a radio program. I’ve forgotten what it was about now, but there was a guy talking for about 20 minutes about his hùmǔ. I had no idea what a hùmǔ was, but I thought that I would find out if I kept listening. After a while, I figured out that it had to be family related. Maybe 护母/護母 (hùmǔ, “protective mother”). Then, suddenly I realised that he had been talking about his parents the whole time! He just pronounced 父母 as hùmǔ, switching “f” and “h”.

Your example

Above are three encounters with regionally accented Mandarin that tripped me up the first time I encountered them. I’m sure that most people who have been speaking Chinese outside of the classroom have plenty of similar examples. What did you find difficult the first time you heard it? Or maybe something you still find difficult? Leave a comment!

Dealing with regionally accented Mandarin as a student

So, where do these examples leave us? It’s obvious that we have to make considerably adjustments to our mental maps of the sound system when we start to speak with people who aren’t teachers or news broadcasters. First and foremost, even before we consider what you might be able to do about it and how it affects communication, it’s important to get the attitude right.

In short:

If you don’t understand what someone is saying to you, it’s your fault

This sounds simple enough, but I’ve heard so many people rage and rant about how people from such and such a place can’t pronounce certain sounds or don’t speak Mandarin in an intelligible way. This might indeed be true, but that’s that’s not the problem.

Will the phenomenon go away if enough foreigners complain about it? No, of course it won’t. So deal with it. This is the way the world works and it’s up to you to handle it. Fuming about it won’t help at all, and might even hinder you.

Instead, start liking regionally accented Mandarin! Make a conscious effort to think “charming” and “interesting” instead of “weird” and “stupid”. A shift in attitude can do wonders. You might still not understand what people with heavy accents say, but at least you’l be open to learning and dealing with the problem.

Some practical advice

While it can be argued that it takes two to tango and that it’s also the responsibility of the speaker to make sure the listener understands, it’s also true that we can’t realistically hope that people will adjust to us as individuals. We can, however, influence what we ourselves do. Here are some things I suggest to help you deal with regionally accented Mandarin:

- Diversify your listening practice

- Experience the accents and learn from that

1.1 Travel around China to immerse yourself in certain accents

1.2 Watch TV programs/shows with normal people in them

1.3 Talk to new people/strangers - Read about the characteristics of these accents (if you know of a good overview online, please let me know as I have been unable to find one)

- Mimic dialects in order to understand them better

Of course, these aren’t mutually exclusive, so I would suggest talking with lots of people and looking up their various dialects.

Regionally accented Mandarin: A matter of practice

As is the case with listening ability in general, learning to understand regionally accented Mandarin is mostly a matter of practice. The examples I listed above were all from my first year in Taiwan and I quickly got used to the way people speak there. That doesn’t mean I’m used to every single dialect nowadays, but I’ve heard enough people with different background speaking Mandarin to not get tripped up by simple and common switches like those. As everybody else (including native speakers), I still struggle with the tax driver from some place I haven’t been and whose accent is new to me.

After you’ve listened to people who switch sound A for sound B for a while, you’ll get used to it. Of course, there are many, many As and Bs, so you need lots of practise, but the principle remains the same. The important thing to understand, though, is that regionally accented Mandarin isn’t that hard to understand once you learn these systematic changes. It might sound like a different language at first, but provided that your listening ability is okay in general, once you break the code, comprehension will increase very quickly.

Unless they really are speaking a different topolect, of course, in which case it’s more like learning a different although closely related language.

Over the years, I’ve gone from thinking that regionally accented Mandarin is dangerous, bad and incomprehensible to thinking that it’s quite charming, valuable and not that hard once I actually try to learn. Combined with my interest in phonetics in general, I find myself analysing and categorising the way people speak. I think this journey could have been completed much, much faster if the thoughts in this article would have been available to me when I first arrived in Taiwan.

That’s why I wrote it, so that maybe you don’t have to take the long way around to figure out how to deal with regionally accented mandarin!

Editor’s note: I’m mostly talking about pronunciation here, but it should be noted that there are of course also differences in vocabulary and grammar. This article, originally published in 2012, was rewritten from scratch and massively updated in June, 2021.

References and further reading

Tang, C., & Van Heuven, V. J. (2009). Mutual intelligibility of Chinese dialects experimentally tested. Lingua, 119(5), 709-732. Accessible online here.

Sommers, M. S., & Barcroft, J. O. E. (2011). Indexical information, encoding difficulty, and second language vocabulary learning. Applied Psycholinguistics, 32(2), 417-434.

新华社. (2017). 我国普通话普及率约达73%. Accessible online here.

Image credit: Wyunhe, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

36 comments

These 12 comments were retrieved manually after a server crash:

Harland: How about adding “tolerate that horrible Beijing accent” to the list? It can be quite jarring to hear it, especially when you live in “the real China”. 儿 is for talking about kids and that’s all.

February 19th, 2012 at 11:09

Sara Jaaksola: Excellent post! Most of your examples sound familiar to me because I live in Guangzhou. I remember when a clothing shop assistant said “you yen” when she meant “you ren” (there’s someone in the fitting room already). I also used to have a teacher who couldn’t tell the difference between n and l. And in the beginning I couldn’t say if my boyfriend (his native language is a sub-dialect of Cantonese) was saying “e” (hungry) or “re” (hot).I think after two years I’m quite used to the way people speak here in Guangzhou. What really puts me of when I meet a person with a strong erhua, adding “r” after almost every word. I had a teacher like this before and it was really hard to understand him.

There also one difficulty here in the south. Sometimes it’s really hard to say if it’s 4 yuan (si) or 10 yuan (shi), also number 7 might be tricky to recognize. Some Cantonese people tend to pronounce all different S-sounds in the same way, it’s all si si si.

February 19th, 2012 at 14:15

WPH: I am from Taipei now live in Sweden. I do recognize the difference between N. and S. Taiwan Mixing up “N” and “L” are indeed very common. Many people also mix up ㄕ v.s. ㄙ and ㄔv.s. ㄘ. The Taiwanese – dialect does not seem to have many words with retroflex initials ( 捲舌音 ㄓZH ㄔCH ㄕSH ㄖ), but more dental sibilant initials (ㄗZ ㄘC ㄙS). Therefore, when the Taiwanese-dialect speakers speak Mandarin, such Taiwanese accent 台灣國語 is very noticeable. Sometimes I wonder if 台灣國語 is actual a ‘natural’ way for language development. I have observed my daughter and wonder about this for a long time. We live in Sweden so I am the only one teaching my kids Chinese here. I have taught my daughter the formal way of pronouncing words since she’s a baby. But still, between 1~3yo, her pronunciation sounded 台灣國語. She just didn’t say ㄓㄔㄕㄖ. When she is older, she’s better with 捲舌音.As a Swedish-language learner, I thought there are also regional differences among Skåne, Stockholm, Gotland, Småland… I thought words starting with “SK” and words ending with “R” are most noticeable. But so far, I don’t think the regional difference confuses most Swedish-language learner. I wonder why is that. Perhaps the teachers have explained in the classroom? Perhaps the words do not alternate the meaning because of the pronunciation?

The comment from Harland about Beijing accent is also interesting. When I lived in USA and had friends from various part of China, this Beijing access with “儿” was also commented by many other Chinese friends (ex-Beijing). “No we don’t say “儿” like that”. The Chinese language used in Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam also have many influences by it’s local languages, Fukianese and Kantonses, and thus have special accent.

I have no intention to promote which way (TW or CN, Beijeing or Taipei) is the best to learn Chinese. It’s learners’ own choice. But it is very interesting for me to meet Chinese native speakers from various background and open up my knowledge. Now I found your blog. It is even more interesting to re-learn my own language, from foreigner’s view, in a structural and more analytical way.

BTW, There is a website that has a collection of phrasis used in TW and CN. Hope you find it interesting too. http://chinese-linguipedia.org/clk/diff/list.do

February 19th, 2012 at 23:14

Niki: This is truly interesting post for me, a Mandarin native speaker. Sometimes I cannot understand Mandarin with accent either. In my family, we use Hakka and Mandarin simultaneously. I found that sometimes my Mandarin is mixed up with my Hakka accent which makes my Mandarin out of the right tune.

February 20th, 2012 at 12:20

Harland: Oh, and just today I saw one of the guanjia’s at work doing some typing test program. She was using Pinyin for some strange reason, maybe she’s not very good with computers. I watched as she tried to type 客户 as “ke fu” and she never got the right character. I had to correct her.Chinese really does suck as a language…as I get more fluent I realize native speakers have tons of problems.

February 20th, 2012 at 13:21

maozhou: @Harland

Where is the ‘real china’? I think most Mainlanders would be annoyed at such a patronizing comment from a ‘laowai’. Like it or not so called Standard Chinese is based on the Beijing Dialect. Its not a matter of tolerating it, it is a fact of life.

February 21st, 2012 at 04:48

vermillon: I think I’m quite accent-biased, but I don’t think it’s an arbitrary bias. The degree of standard-ness of a speaker is strongly correlated with their level of education and socio-economical situation, anywhere in any country. Then it’s up to the learner to decide what kind of person they want to communicate with or listen to, obviously, and if they want to communicate perfectly with shopkeepers, then I’d say “go for it”.To nuance what I’ve just said, I think we should not confuse it with a China/Taiwan problem, which would be like saying which of British or American English is standard. Each of them has its “general accent” and that’s indeed something you need to adapt, but these are broad changes that one can easily adapt to.

Finally, the fact that Niki says he can’t understand some other people shows, imho, that it’s not “our fault” if we don’t understand. That’d be the same if I claimed that it’s not my fault if Chinese people can’t understand my speech just because I have my own accent and way of pronouncing things in a non-standard way (I’m particularly thinking of “blurring tones altogether” compared to “blur z/zh, c/ch etc”).

February 22nd, 2012 at 11:15

Olle Linge: Hi everybody and thanks for sharing your thoughts, it’s always interesting to see how other people think. I don’t have much to add, but I want to highlight to things:

1) The website WPH shared is really useful for anyone interested in weeding out differences between usage in Taiwan and on the Mainland

2) I want to point out that I said “it’s your fault” because this attitude is helpful when learning, not because it’s necessarily true (if taken to extremes, you could argue that it’s your fault that you can’t speak all the languages on earth, which is obviously daft), the point is that if you blame others, your shifting focus to something over which you have no power whatsoever

February 22nd, 2012 at 13:40

vermillon: Agree on that last point, though of course, it can also be healthy to know when to say “it’s not my fault”, to focus more on something else. Learning is supposed to be “fun” they say, and guilt is usually not very fun.You can see learning (to recognize, or even speak!) different accents, and that can be fun if that’s the person’s interest. Personally it’s clearly not one of mine, so I prefer to consider it’s not my fault and focus on other things I’m more interested it. “zen”

February 24th, 2012 at 13:01

maozhou: @vermillon One thing I do is to try to remember my three children and what it was like when they began to speak. They didn’t worry about being correct or grammatical. They wanted to get the idea across and if they said something really wrong or embarrassing they thought it was funny and just laughed.So I try NOT to worry so much and just copy the accents and structures that I hear. The Chinese are infinitely patient with foreigners if they are sincerely trying and will gently point you in the right direction. I take every opportunity to chat with strangers and people on the street.

I have honestly never had a bad experience and have learned much of the local dialect. Not just Putonghua but Beijing Hua and a lot of great “lao Beijing” slang. The grimmest most unfriendly people break in to a grin and begin to chatter away if I greet them like a ‘lao Beijinger”. It comes in handy when you are trying to get a taxi driver to drive you to Shunyi at 4:30pm on a Friday!

I have also through this approach met some very interesting and prominent people who by their accent and dress would not appear at all highly educated or connected. I’ve learned not to judge a book by its cover or accent.

February 26th, 2012 at 07:08

maozhou: @Sara Jaaksola How true! I’ve also noticed that from my Sichuan friends who in addition pronounce my mingzi Zhou as more like dzhou! One of my favorite sports is to go to the silk market or yashow in Beijing and chat with the sales people and try to guess their home province.

February 26th, 2012 at 07:12

Selly: When I started lessons with my current Chinese teacher in late August of last year, I was shocked to find out that I couldn’t understand her at all. Up until then I’d been living a very sheltered live in terms of wonders of regional dialects Mandarin has to offer. My first teacher was from Northern China but she lived in Beijing for a long time and speaks perfect standard Mandarin with the pronunciation just as it should be or so she kept reminding me whenever I messed up my pronunciation which happened (still does) at least 12 times a lesson. My teacher shared some funny stories with regards to different regional dialects but I mostly laughed them off, thinking I wouldn’t have to deal with them for a good while. But then, like I said, I changed teachers and during our first lesson I spent about three hours panicking over the fact that I had a teacher, from the very south of China, whom I couldn’t understand. I think she sensed it for she spoke really really slowly and accentuated every word. Nada, still didn’t get her. We got there eventually and now we have our own little inside jokes which are mostly related to my standard mandarin going downhill to a lovely lazy Taiwanese accent and I actually find it quite difficult to speak standard Mandarin now. I have been thoroughly southernised. The funny thing is that since most of my friends are from Southern China they are worried that I don’t understand Northern Chinese when we go to a restaurant, etc. it is a whole load of fun to surprise them by chatting away to the waiter while they are idly wondering why on earth I understand the accent. Dialects are wonderful things really, they make for amazing misunderstandings sometimes and are the cause of much laughter, at least among me and my friends.

February 27th, 2012 at 20:16

This article is excellent. I encounter people from many different regions and I have been trying to understand differences in pronunciation. This is a difficult subject to discuss for several reasons. I have not studied Chinese language for a long time. Some speakers do not have as much exposure to Chinese speakers from different regions. Different regions use different terms to communicate about parts of language. I will try and spend some time on the web site http://chinese-linguipedia.org that WPH shared

Thanks a lot for this article! I appreciated the examples, and I’m looking forward to hearing more of the variations when I live in Taiwan this year.

I too can’t stand Beijing and Northern accents in China, they do way too much tongue rolling and add ‘er’ on the end of everything. The best sounding accents are Fujian, Taiwan, and I guess newscaster Mandarin, they flow smoothly and aren’t harsh.

If you think about how an accent of a language becomes the prestige accent and regarded as standard, they are often an accent not from the capital. For example, the General American accent (or sometimes called NPR accent) for US, which is from the Mid-West, rather than the accent from Hollywood or New York. RP for British English, a southern accent spoken by the educated, and not an accent from London. In French, the accent of the Tours area, which is considered the best, the most beautiful. Also accent from the the Toulouse area is considered the most sexy.

I think it’d be more healthy to think of Mandarin like how the Spanish is spoken in Spain. While the locals speaks Basque, Catalan, Galician, or Occitan, while everyone speaks and understands Spanish. Don’t most Taiwanese people speak both Mandarin and Hokkein / Hakka and switching them back and forth ?

I can’t say which accent is the best. But one certainly hears mandarin spoken more often (well, to be honest, yelled out by Chinese tourists) all over the world. I always think a language is part of the country’s culture. I once talked to a young student from China and he was telling me how nice China has become. I had to stop him — a country whose pollution’s level is literally off the chart. A country whose citizens often have to go outside the country to buy baby’s formula because they don’t trust its food supply. I can go on… What’s there to learn and to admire ?

You started talking about accents and then went on spreading hatred. No one needs you to continue your rant about everything bad in China. As if your country was so perfect.

A resource I’ve found to help with understanding regional dialects is “A Bite of China” (舌尖上的中国). It’s a beautifully produced series on foods which covers all regions of China. You can find it on YouTube.

I think that map is not very accurate or correct. Because I live in Chongqing and the dialect that is being spoken in Chongqing as well as in Sichuan is nowhere near mandarin or like standard mandarin. I would class the sichuan/chongqing dialect as its own dialect and not mandarin because even Chinese people visiting this city has real troubles to understand the locals. Old people here can’t even speak mandarin, even some young people has huge troubles to speak standard putonghua.

I work as a medical interpreter in the US. Passing all the tests in order to become a certified interpreter takes time but it can be done. Learning all the medical vocab also takes time but can be done. The most difficult part of interpreting (besides all the non-Chinese related communication stuff) is the regional accents. Even the nationally certified native Chinese speaking interpreters have lots of trouble understanding people when they speak a dialect or with a heavy accent. The only way to combat this in my experience is to listen a lot to these dialects and accents. Hujian = Fujian, li = ni, etc.

Indeed! I think we can perhaps find some solace in the fact that native speakers also have problems with this, as you say. That doesn’t make the situation less problematic, but at least it’s not your fault. 🙂

Great article Olle! My Wu-accented Mandarin examples are “sh” converted to “s” (Sanghai for Shanghai, “say” for shéi 谁) and “zh” to “z” (Hangzou for Hangzhou). The most unusual things I’’ve heard on Chinese language CDs (and even in Pleco) are “Ying-yong” for Yīngyǔ, chee-yung for qǐng 请), and “vey” for “wei” (w to v transition) as in 为什么 – these are apparently northern variations.

Great piece.

You should do one with common variations on Mandarin for different regions. I think it’s often surprising for a beginner that f/h n/l sh/s get replaced, but it would be interesting to know which changes correspond to which regions!

Here in southern Jiangsu I often meet people from northern Jiangsu who don’t distinguish (even switch) sh/s. So when my tones early on weren’t so good someone saying shi4 was actually saying 四, but I heard it as 十 (and vice versa)

Yeah, I remember sometimes having problems with the difference between “tenth floor” and “fourth floor” in elevators because of this.

A valuable insight into Chinese Mandarin. I have bee slowly learning buts as I travel, but I have been caught out with regional variation. I’d learned that a pinyin ‘c’ on its own is pronounced as a ‘t’ so ‘can’ would sound more like ‘tan’. (rough approximation). But in lots of places the ‘ch’ still sounds like ‘ch’ as in ‘chew’. That was fine and I was going with it, until I got to Chengdu and was asking for taxi’s and orange juice. chuzuche and chengzhi. I got blinks of incomprehension in reply. Fairly quickly I found out that they change their ch sound to a ‘t’ sound as well. Taxi sounded more like (excuse my phonetics) too-zoo-ter. Indeed they pronounced Chengdu as more like Tengdu. I think this interpretation is fairly widespread in that part of China.

The other thing that I take away from this is most native Mandarin speakers in their home-towns have pretty tight front-end filters on their language. I mean, in English, I have been exposed to and can understand English with heavy Scot, Indian or deep-south American inflections, all fairly well, despite these huge variations. In China it seems that I only have to be 2 or 3% off the local norm and they don’t have a clue what I’m trying to say. (and I don’t think they’re faking it) I put it down to the locals not getting around much and not hearing anything but local dialect for most of their lives. Just another layer of difficulty for a wannabe Chinese communicator.

Still, I can get my revenge upon Chinese tourists visiting Australia by replying in rhyming slang… Maybe they just think I’m a Merchant Banker.

I also love the fact that there’s variation in a language, and I hope people keep having these different accents and their own ways of pronunciation. But still, it doesn’t hurt as a native speaker to sometimes get your shit together when a language learner doesn’t understand you.

I’m meeting many learners of my native language, and because I also have a heavy accent, I make an effort to speak more standardized (depending on their level ofc).

Yes, I would do the same (although my accent in Swedish is so mild that most people can’t tell where I’m from for sure). However, I still think we don’t really have a right to demand than someone does this, even though I agree that adjusting to help a foreigner is the right think to do. Some people might not be able to, though, or may not be aware of the problem.

I wonder why you didn’t remark on how all your examples are of variation in how consonants are pronounced. It seems to me that this is a major difference between speakers of tonal and other languages: the former listen principally for vowel pronunciation, while the latter generally construct a mental framework of sounds based on consonants.

I don’t know what the right answer is here, and as I said, I haven’t been able to find a good study that tallies up different types of issues. However, it’s certainly not just an outsider perspective. When talking about accented Mandarin in Mandarin with native speakers, the examples I brought up are among the most common ones, but also of course the retroflex series and sometimes the alveolo-palatal series as well. Finals are mentioned, but the only very common one is -n/-ng in various words. Maybe -iu as well.

I can’t come up with many good examples where this caused trouble for me, though, and the examples were of course my own. Do you have examples where you misunderstood what someone was saying because of differences in finals? My family name is 凌, which is often rendered the same as 林, which sometimes causes trouble, but that’s the only case I can come up with!

There might be something to your argument about tonal languages, but I think vowels are more important in English too. I found one study that says that the vowel information is even more important in Mandarin, but this is not exactly what we’re talking about here, but here’s the reference if you want to check it out:

Chen, F., Wong, L. L., & Wong, E. Y. (2013). Assessing the perceptual contributions of vowels and consonants to Mandarin sentence intelligibility. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 134(2), EL178-EL184.

And:

Chen, F., Wong, M. L., Zhu, S., & Wong, L. L. (2015). Relative contributions of vowels and consonants in recognizing isolated Mandarin words. Journal of Phonetics, 52, 26-34.

Thanks for the references. I hadn’t thought of distinguishing further between types of consonants depending on their position related to syllables.

Not really pertinent to the discussion, but vowel sounds in English vary so widely, and as has been pointed out, there is so little resistance to understanding variants, that I’d dispute your suggestion they matter very much for comprehension in English. However, as a Scot in the UK whose pronunciation of a much more limited range of vowel sounds (probably from a Gaelic substrate) is the local norm, I find the many English voices that all seem to be chewing while pronouncing vowel sounds very distasteful! As we say in English, chacun à son goût! 😀