In other articles on Hacking Chinese, I discuss how you can learn characters, words or grammar patterns more efficiently. Since all these articles rely on a common theme, it seems reasonable to give an introduction to that theme along with some more detailed information and help. The general theory is that disassociated learning, i.e. learning things that aren’t connected to something else, is bad, and that you should at all times try to associate what you learn with something you already know. This is the essence of holistic learning even though this post will deal more with details and memory aids in general.

Note that this post is not about the practical aspect of memory aids and mnemonics. There are two other articles of interest that describe how to apply these principles when learning characters and words:

What we’re going to talk about here is the principle behind these posts and mnemonics in general, so if you want hands-on information on how to improve your learning, checking those two articles is probably better than reading this one. If you want to know more about tricks to boost your memory, read on!

What is mnemonics?

If given a list of random numbers or words, how many could you remember after studying the list for just a short time? The usual answer is 5-9 items, because that’s what normal people can hold in the working memory at any given time. If you want to remember more than that, you have to use some kind of technique. With a very simple method, you can easily remember thirty items in order and without fault. It will take some practise getting good at it, but it’s not hard. In the case of words, simply connect the words with each other in a unique way. If there are numbers, you typically have to convert them to something else that’s easier to remember first (like letters). This requires preparation, but is worth it.

The most important thing that a good memory can be achieved through practice, it’s a skill that can be trained.

The story method

The first example is an easy method where you simply connect the words to each other directly. If the words are limousine, paper and elephant, war, Paris and green (this is just an example), you connect these words by by picturing a well-dressed elephant sitting in the spacious back seat of a limo, reading some papers, while the car is moving through war-struck Paris (perhaps with the Eiffel Tower broken) and enemy aircraft dropping green paint over the entire city. A story like this takes seconds to create and with practise you don’t even need to think. If I ask you tomorrow what the five words were, would you be able to recall them? I think you would. If not, the story was not good enough or didn’t suit you, but more about that later.

The journey method

The journey method relies on similar principles (everything does, really) but instead of a story with things going on, you picture yourself on a journey, preferably through an environment you are familiar with. Along the way, you encounter the words, people or whatever you want to memorise. This is nice because you don’t need any preparation and is thus easy to use on the fly. Using this method, you might picture yourself walking to school/work and along the way you will see lots of things happening, preferably interacting with the environment.

The loci method

The third and last example is perhaps very similar to the second one, but I want to bring it up anyway because it’s so useful. The above technique used spatial memory to associate something meaningless with a well-known structure (i.e. the road on which you make your journey). The loci method is simply a general term for techniques that make use of this ability of the human mind to remember things (it’s also called “memory palace”).

It’s important to realise that the environment doesn’t have to be real! You can prepare certain rooms beforehand, which only exist in your mind and then later use these to store information. This is for instance very common for multiple blindfolded cubing, i.e. where people look at several Rubik’s cubes and then solves them in succession without looking. It’s actually a lot easier to do that most people think, but it would be hopeless without some memory aids like the loci method.

How to associate A with B

All these methods and all holistic learning is based on the principle that you can connect more or less random pieces of information with each other. Sometimes the connection is logical and it comes naturally without having to think too much about it. This is true for any kind of association which fits perfectly into our overall framework for a certain subject. If you encounter a word you haven’t seen in Chinese, but which follows every single rule you know and just makes sense in general, you won’t forget the word easily. However, languages are naturally evolved and there will naturally be lots of situations where you have to create the link yourself, using your imagination and previous knowledge.

You can base your links on many different kinds of associations which will probably work differently for different people, here I will simply share my own experience. This list of how links can be formed just contains some examples, it’s not exhaustive and you will be able to add your own. I will use random words to associate here, simply because I talk specifically about Chinese everywhere else and because it will be a lot easier to find examples that anyone can follow, regardless of language ability.

Five characteristics of a good mnemonic

- Absurd – Usually, the more exaggerated the picture you form for a certain connection is, the easier it will be to remember. Relying on logic is not very good here, so if you want to remember the word “Santa Claus” and “reindeer” it’s not a very good idea to picture Santa sitting in a sledge pulled by reindeer, because this is reasonable and easy to forget. Do it the other way around! Think of Santa pulling a sledge full of reindeer. Make big things small, few things many, overturn any kind of logic you can find.

- Shameful – Any kind of embarrassing link is good, especially if it deals with taboos. Sex is awesome (from a pure language-learning perspective, of course). I’ve heard this from almost everybody who uses this kind of associations, that the shameful and embarrassing associations are those that stick the longest. What is embarrassing for you might be different from what is for me, but I think you get the idea.

- Disgusting – Any association which is revolting and very unpleasant is also likely to be stronger. Again, it differs greatly what people think is disgusting, but you can probably come up with connections that involve all three points I’ve mentioned so far, even though I’m not going to give you an example of that here!

- Scary – What are you afraid of? Using the answer to that question is also likely to enable you to form stronger connections between words. I’m not afraid of many concrete things (such as snakes or spiders), so I don’t really use this very often, but picturing scenes that are in some way scary is still possible.

- Funny – Try to use humour as much as you can. Why? Because it’s fun, of course! On a more serious note, funny things are also easier to remember. Typically, funny associations are also absurd, but they don’t have to be. Note that it doesn’t matter if anyone else thinks it’s funny or not as long as you do.

The list can be made longer. Do you notice any common theme? Yeah, that’s right, strong emotions and things that are unique.

Make your connections vivid

If you follow the above-mentioned principle of using strong emotions, make sure that you also make your associations as vivid as possible. A connection is often a mental picture of how two things interact with each other. It’s very important that you don’t simply say the two words together in a sentence. Saying “Santa pulling reindeer” is a connection that will probably fade over time. What you need to do is use all your senses and try to make the scene as vivid as possible. Smell the sweat running down Santa’s back, hear the cracks as he’s being whipped by the reindeer, see the haughty looks on their faces.

If you feel that this is difficult, don’t worry! Most people require practise to become good at this, but fortunately it’s both quite easy and occasionally also entertaining. Simply imagine yourself noticing details in the scene, making the impression of it stronger.

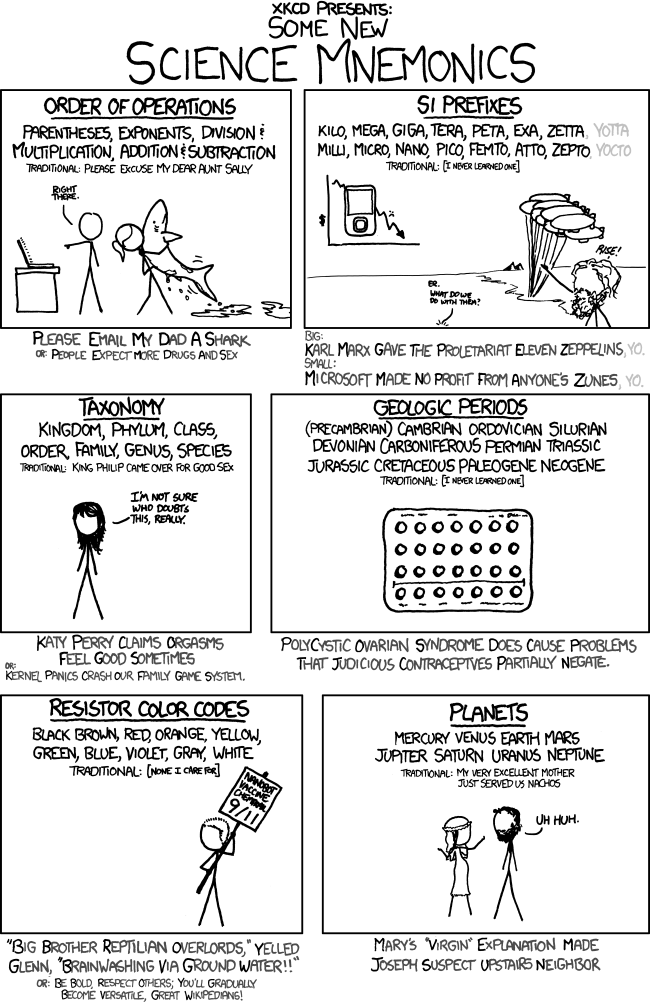

Here are some excellent examples from xkcd:

Connections are your own

If you have strong emotions combined with vivid pictures, you will quickly realise that some associations aren’t suitable for publication. That is not a problem, because no one will force you to explain the associations you have made. Regardless of how taboo something is or how revolting or silly (or both) a specific connection is, it doesn’t matter because you are the only one who will ever know. The only two categories that are really suitable for sharing are the absurd and funny ones, and it can be truly entertaining to read what bizarre associations other people make!

Maintaining connections

Even if you’re an expert, there will be connections that fade quickly for some reason. Sometimes you can spot the problem and you understand why you can’t remember it. In cases the solution is obvious, just make the connection stronger by changing the association a bit. At other times, though, you just can’t remember something even though you think you should. Don’t hesitate to recreate the connection in these cases, abandoning principles that don’t work. After doing this for a while, you will know more about yourself, what works and what doesn’t.

Good connections can last a very long time. For instance, if given the start of a story I’ve used for blindfolded (Rubik’s) cubing, I can sometimes remember the complete story, even if I did the solve weeks or months ago, and I didn’t even want to remember it for longer than five minutes! However, if left completely alone, most images fade, if not in days, weeks or months, then years. Therefore, you need to go through your web in various ways. Since we’re talking about language learning on this website, it’s quite easy to do that, but it’s still important that you do it. Use the language a lot, listen and read as much as you can and use spaced repetition software to make sure you know what you need to know. These are all ways to use the words you have and after a while you don’t even need the connections any more. Maintaining connections is also a central of spaced repetition software, such as Anki.

Further reading

There is a plethora of information on the internet about memory techniques and using any search engine will give you more information than you can possibly read. Look at what other people have said; trying it is the only way to know if it works or not. By way of concluding this article, I’d like to share a few of my favourites:

- The memory methods thread on Speedsolving.com

- Memory methods at ChangingMinds.org

- The article on mnemonics at Wikiepdia.org

Questions for the reader

- What memory methods do you use?

- Do you use these methods for other things than Chinese?

- Do you have any other tips, tricks or suggestions?

46 comments

Do you know where I can find printable flashcards? I checked out zdtwordlists and they have some but I’d like the pinyin and english on one side, Character on the other…

@Dan: If you have access to any kind of computer or smart phone, I see no reason to use printed flashcards since they are severely limited compared to computer software. Thus, I haven’t tried to find programs providing this function and I can’t help you more than saying that there should be such programs and a little googling will probably allow you to find them.

I have learned Chinese for 2 years, finally, my Chinese is still very low so far.

Do you have comments for improving Chinese better. Hop I can receive your good advice.

Thanks

Sinith

This entire website tries to answer that question. Check the categories in the right-hand menu (top on mobile), select which category you’re interested in and see if you find anything interesting!

I have found a new (to me), fun use for mnemonics.

I’ve been cramming new characters for 3 weeks now as I plan to learn a few hundred in a relatively short time. Based on the suggestions of this site, I use mnemonics built with the components to learn the meaning of those characters, which seems to work well up to now. However, I often have problems learning the pronunciation. The reason may be that, by definition, these are characters I’ve never seen, used or heard, so I’m condemned to learn them out of context, which I hate.

Now, I’m trying to use mnemonics not only for the meaning, but also for the sound.

I don’t rely on vague comparisons with my mother tongue or English, which are too different from Chinese, making any approximation useless. What I’m trying in some cases is this: if I can’t seem to learn the pronunciation of a character (say 翰, han4), I find other characters with the same pronunciation and I invent a one-sentence story (the more striking the better), say: “Writing with a brush 翰 dipped in sweat 汗 is a Chinese 汉 specialty”. Now, most probably, I know the pronunciation of at least one of these words. Ergo I can remember the pronunciation of all of them.

Of course, many people will tell me that learning yet another mnemonic is, by itself, an additional burden. To which I reply that the mnemonic, in my experience, tends to vanish rapidly from memory while its effect, i.e. having learnt something, tends to last. Second, I believe this is an efficient way of using mnemonics, since I can learn the pronunciation of several characters with one sentence. Besides, a new, unknown fact is tied to a network of previously learnt facts. I even suspect that such sentences will help me remember not only the pronunciation, but also the meaning of the character(s). Finally, I’m not saying that this would be useful for everybody or in every case. However, it certainly has been for me, in many cases.

This is interesting in more ways than one. Before I say anything else, I’d like to point out that the whole idea with a mnemonic is that you don’t have to spend time learning it. You create it and it’s so vivid that you don’t have to review it actively at all. Sure, it pops up now and then when you study, but you don’t need to work hard. If you have to review a mnemonic, you’re doing something horribly wrong. 🙂 I’m not suggesting that you are, I’m just supporting your approach.

I’ve basically come across two ways of memorising tones for tricky characters: using colours in mnemonics (e.g. paint stuff red for first tone, blue for fourth and so on) and associating the tone with the character itself (a teacher of mine did this, like remembering it’s third tone because the character starts with 氵). I think the first method is quite good, the second is fairly limited. What you suggest is interesting though, because if the sentence is vivid and clear in your mind, you don’t really need much more. I actually use this sometimes, even though I didn’t realise it could be done the way you’re doing it. I usually remember long words (or idioms) that have characters pronounced with the same tone. It’s easy to remember that 俱乐部 is three fourth tones or that 第二次世界大战 is all fourth tones. This isn’t exactly what you’re doing, but close enough.

Could this be mixed, added, amended or something?

Another great post Ollie!

Reminds me of this book (author of no relation to me) called Moonwalking with Einstein. Basically a journalist goes into the world of memory masters and becomes one himself.

My biggest takeaway was that memorizing things isn’t an 死记硬背 rote memorization, but an act of creativity, like you mention here.

@Alan: Sounds interesting. Is the book worth reading? I mean, in itself, not just because it teaches you things that can probably be found on the internet. 🙂

Hi I have been reading this website over the last few days and want to adapt my study methods.

Previously I had been learning individual characters with no understanding of the components. Recently I purchased a book by Turtle ” Learning Chinese Characters – HSK level A” which I now know uses mnemonics to help you remember elements, then creates stories to help you connect these elements.

If I now start to compile a separate list of radicals and components making my own mnemonics, am I likely to get everything mixed up and confusing my self?

The whole concept of Holistic learning and Mnemonics is very new to me, so I don’t want to put a load of work in only to realize I have approached incorrectly.

Thanks.

Hi David! I don’t think you’re likely confused. I started learning radicals and character components from day one and I didn’t feel very confused (more than anyone else who has just started learning Chinese, that is). Learning a character component is just like learning a normal character, but usually easier. I think making your own mnemonics is a good idea, simply because these are very individual. What I think is great might be useless to you, and vice versa. Still, I would try to go a bit easy on the components if you’ve just started. Learn components you see more than once, but don’t bother to learn every single component you ever encounter. There might come a time you’ll want to do that, but it comes very late, if indeed at all. Good luck!

Olle, how would you use the journey method, for example, for learning Chinese? Would you create an example funny or absurd sentence using all of the words you want to learn? I’m interested in giving it a go, but can’t see how it would be applied?

I thought Journey method is a little more useful if you need to remember a list or a group of items (e.g. your shopping list, or the names of the 7 dwarfs).

So if you wanted to remember the 8 main cuisine types in China, you might find this useful. If you just want to how to say each one you can create absurd images/stories for each one. But if you need to list them all out on demand, you need to link them together – so journey or loci are good for this – and you can link each image/story to a location along a journey.

Thanks for that great article. I just watched a TED Talk about this and was sure there will be something about the method of loci on hackingchinese. 😉

But actually I’m not quite sure yet how to actually use it to learn Chinese better. Would I first have to start building my imaginary house and then start adding words (in the form of silly mnemonics as laurenth [see above] does)?

Maybe the idea still sounds like a lot of work as I haven’t started building my imaginary house yet?

On a basic level, the thing you should take with you from the video is that you need to connect things together in meaningful (albeit strange) ways. The house it optional. Read more about characters and words, starting here: Creating a powerful toolkit: Character components.

I started learning Chinese with a simple story/picture for every Pinyin pronunciation. For example, I see a window, with a bed in it, a man breaking in and a cut on his hand. In this order (the 4 tones order) I can remember the pronunciation of ‘chuang.’ Chuang1 = window; Chuang2 = bed; Chuang3 = to break in; Chuang4 = cut, wound. Very simple for pronunciation (at least for me). 🙂

I’m an absolute beginner at Chinese, and have been looking for a method like the one you describe, Michael. Could you (or anyone) tell me where to find a directory of Pinyin sets like the ‘chuang’ set you describe?

I’m surprised no one here mentioned Heisig’s method (primarily developed for learners of Japanese kanji but now extended to hanzi): here’s the beginning of the book where the method is explained: http://nirc.nanzan-u.ac.jp/en/files/2012/09/RH-Simplified-sample.pdf. Someone even developed a flashcard-based website allowing people to share their stories: http://hanzi.koohii.com/ (for the hanzi version). Unfortunately, the community of users using it for hanzi is not very developed yet (unlike the Japanese counterpart) but it’s still a great tool.

Hi, I’m learning Chinese since three years, but first this year started to learn characters. Thus my speaking and listening is far ahead of my reading skills.

That brings the need of learning quite a lot of characters in a short time frame.

Rote learning is a pain. For some characters I have stories, but it’s only very few.

One general question is on my mind: composing the story is one thing, but do you write down the story? Or memorize it until you have it embossed into your neurons?

What’s with your stories one day later? Give days later? Do they vanish? Most likely a lot of them will fade away. Do you invent new stories then?

I normally don’t do stories, just a single scene or picture that is easy to remember (think of something that could potentially be shown in one single frame). And yeah, I normally remember them, that’s kind of the point. If I forget them, I come up with a new one and hope it sticks. After doing this for a while, you learn what works and what doesn’t, so you’ll get better at coming up with associations that stick. I never write any mnemonics down.

Understood. Thanks a lot.

Dear Olle,

I am new to Chinese. Please suggest if I want to start with a reading skill first. For other skills (speaking, listening, writing) are the next steps.

Thank you.

Jo

I normally recommend people to start with the spoken language, unless you have a particular reason for not doing so. Delaying learning characters is mostly a good thing, something I wrote more about here: Should you learn to speak Chinese before you learn Chinese characters?

Hello, and I must say I am very impressed with your website’s extensiveness. I’ve looked for the better part of an afternoon and evening at various links in your website. I was initially drawn in by the TED talk video that you strongly recommended, which was really motivating.

However, I am having trouble comping up with ways to apply the memory techniques (such as memory palace or object association) specifically for learning writing, and learning more vocabulary.

I am in a bit of a unique position in which my family sometimes speaks Chinese, so my pinyin is mastered, and my spoken Chinese (at least for everyday use) is stronger than any of the other forms, with writing being especially problematic (I’m learning simplified). I’m already familiar with semantic-phonetic characters, the basic stroke orders, and ~50 of the most basic characters.

With that in mind, would it be possible for you to share some examples of mnemonics you used to learn writing, so I can take some inspiration? For example, here are some of the words I’m having trouble with right now: 就表决要办快简成.

For more context, these are from a beginner textbook from China.

Gratefully,

Hexa

Did you try to use memory palace for learning characters? How would you represent the information? One image for let’s say the English word, one for the Pinyin (without tone), another one for the tone..or would you create a list of images you can reuse for the finite set of initials and finals + the tones? It’s a lot of work, I’m trying to understand how I could encode all the information I need with the least effort possible.

No, this seems like massive overkill in most cases, so I never did more than play around with it. One problem is that you need a lot of pegging, because you can’t just place actual combinations of strokes anywhere, and once you’ve learnt many hundreds of components and then how characters work in general, you don’t actually need the memory palace. I guess it could be useful if you’re trying to construct encyclopedic knowledge of rarer characters or maybe character etymology, but I’m convinced that for the average learner (even the average learner interested in memory palaces), it’s not a wise investment of time! I wrote about something related to this here, actually: https://www.hackingchinese.com/dont-use-mnemonics-for-everything/