Most Chinese character components are well-behaved; they look the same in different compounds and aren’t hard to recognise. Some components are sneaky, though; they change appearance depending on context.

Most Chinese character components are well-behaved; they look the same in different compounds and aren’t hard to recognise. Some components are sneaky, though; they change appearance depending on context.

One of the major challenges when learning to read and write Chinese is that the link between the spoken and written language is not obvious and sometimes non-existent. By realising that characters that look different are actually the same, you make the learning process a little bit easier, so let’s have a closer look at these shapeshifting characters!

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

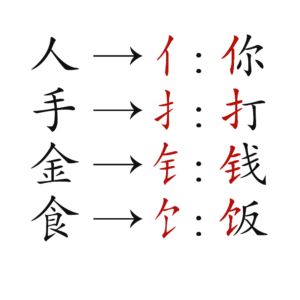

An example: 人 changes shape to 亻 when on the left in compounds

Let’s begin with an example most readers will be familiar with. The character 人 (rén), “person”, is written as 人 when used as a stand-alone character, but when it appears on the left side of compounds, it’s written 亻. In Chinese, this component is called 单人旁 (dānrénpáng). Here are some common compound characters with this component:

- 你 (nǐ), “you”

- 他 (tā), “he; him”

- 休 (xiū), “rest”

It’s still the same character, though. It contributes the meaning of 人, “person”, to these characters and is best thought of as a different form of 人 rather than as a new character. This is not obvious if it’s the first time you see these characters, however. There are characters that are much more similar than 人 and 亻 that do in fact mean different things! If you want to know more about this, I’ve written a series of articles about it over at Skritter.

Another sign that they are indeed the same character is that when in characters where it’s the phonetic component (i.e. where its function is to indicate sound), the pronunciation is still rén. For example, in the character 仁 (rén), “benevolence”, 亻 is the phonetic component, which is not hard to guess since the whole character is also pronounced rén.

Colloquial names for shapeshifted Chinese character components

Still, when talking about 亻, Chinese people don’t just say rén because that would make it impossible to distinguish it from 人. Instead, all common character components have colloquial names, and so 亻 is called 单人旁 (dānrénpáng), “single-person-side”. For a more comprehensive list of colloquial names, check this table from my article about the 100 most common Chinese radicals:

Kickstart your Chinese character learning with the 100 most common radicals

Note that the colloquial name is not always a reliable indication of the origin or meaning of the component in question. For example, the component 彳 looks very similar to 亻 and is even called 双人旁 (shuāngrénpáng), “double-person-side”, in Chinese, but it’s completely unrelated to 人. Instead, it’s the left side of 行 (xíng), originally showing a road intersection, often included to point out movement or action.

You’ll learn these easy cases just by looking at them…

Most characters simply get a bit squeezed when they are written in compounds. For example, 口 (kǒu), “mouth”, becomes smaller in a compound like 喝 (hē), “to drink”, and 子 (zǐ), “child; son”, needs to be more narrow to fit in the character 好 (hǎo), “good”), but since these are essentially identical, there’s no reason to discuss them further here.

Many characters do change shape when appearing in compounds, however. We already looked at 亻as an example, which is just a slightly morphed version of 人. Once you’ve noticed that, you’re unlikely to forget that they belong together. Here are some other cases that are equally easy to learn:

- 手 (hand): 扌(left) as in 打, 龵 (top) as in 看*

- 牛 (cow): 牜 (left/right) as in 物 or 件, ⺧ (top) as in 告

- 示 (altar): 礻 as in 视

- 竹 (bamboo): ⺮ as in 筷

- 羊 (sheep): ⺶ as in 着, ⺷ as in 美*

- 衣 (clothes): ⻂ as in 裤

- 足 (foot): ⻊ as in 踢

*See “Everything is not as it seems” below for details.

…but some cases require extra attention

Naturally, it’s somewhat subjective which shifts in shape should be considered tricky, but here are some that are not obvious if you haven’t seen them before. Some of these are easier to see in traditional characters, though:

- 刀 (knife): 刂 as in 别

- 心 (heart): 忄 (left) as in 忙, ⺗ (bottom) as in 慕

- 水 (water): 氵 as in 没

- 火 (fire): 灬 as in 热 or 熊*

- 犬 (dog): 犭 as in 狗

- 玉 (jade): 王 as in 玩

- 言 (speech): 讠(simp.) or 訁 (trad.) as in 说/說

- 肉 (meat): 月 (simp.) or ⺼ (trad.) as in 胖**

- 金 (metal): 钅 (simp.) or 釒 (trad.) as in 钱/錢

- 食 (food): 饣(simp.) or 飠 (trad.) as in 饭/飯

* See “Everything is not as it seems” below for details.

** If you wonder why this character doesn’t have a traditional counterpart, check this article.

The last four examples are good examples of why traditional characters might be easier to recognise, even if they take longer to write. For a complete discussion of this topic, see Are simplified characters really simpler to learn?

Shapeshifting Chinese characters with subtle differences

The differences between the stand-alone and component forms of some characters are extremely subtle, and you might not have noticed some of them even if you have studied Chinese for a decade or longer. Let’s do a mini-quiz!

- What’s the last stroke in 车, “vehicle”?

- What about when it appears in 轻, “light”?

- What’s the last stroke in 牛, “cow”?

- What about when it appears in 特, “special”?

The answer is that the stroke order changes when these characters get squeezed into the left component position in compounds:

- In 车, the last stroke is ㇑

- In 轻, and other compounds, the last stroke of 车 is actually ㇀

- In 牛, the last stroke is ㇑

- In 特 and other compounds, the last stroke of 牛 is actually ㇀

These examples are from a blog post over at Skritter, which also includes the following helpful animations where you can compare the stroke order:

I can hear some of you wondering why on earth the Chinese writing system is so needlessly complicated, but if you think about it, this difference in stroke order makes perfect sense if you consider that to write the next component, you have to move almost straight up, and that’s just easier to do from a ㇀ than a ㇑!

How to deal with shapeshifting characters as an independent student of Chinese

As I have shown in this article, there are two categories of shapeshifting characters. First, we have the easy cases where simply seeing them together once and paying attention is probably enough. For these characters, you don’t need to do much, so let’s move on.

Second, we have tricky cases that might take a long time to learn if you don’t give them some care and attention. If you’re not careful, you might think that these are indeed new characters you didn’t know, so looking them up or seeing them in the list above can be very helpful. That is indeed one of the reasons I wrote this article!

Still, I don’t think it’s a good idea to study shapeshifting characters explicitly in detail, especially not out of context. You don’t need to add the examples in this article to your deck of flashcards, for example. Reading this article should be enough to make you aware of what’s going on; the rest will come with more reading and writing. Flashcards are great for learning some things, but you shouldn’t adopt the habit of relying on them to learn everything.

When you learn more about characters and do look things up in a good dictionary, you’ll notice that some things that look different are the same, and that some things that look the same are different, something we’ll turn to next.

Everything is not as it seems:

Not every component that looks like a certain character is actually that character. If you’re just after a quick way to memorise a character, you might not need to delve deep into how it evolved, but if you want to understand Chinese characters, you need to know about something called “empty components”.

Empty components are components that express neither meaning nor sound. In other words, it’s not a meaning component (such as 扌 in 打) or a sound component (such as 亻 in 仁).

You can’t know this just by looking at the character, but the 龵 in 看 (kàn), “to see”, is not actually 手, “hand”, even though folk etymology says it’s a hand shading an eye. It is in fact an empty component and used to look very different. This might not help you memorise the character, however, so if you think the hand-shading-an-eye mnemonic works, then stick with it!

Another example: the 灬 in 熊 (xióng), “bear”, is not actually 火 “fire” as indicated above, but is instead a corrupted version of 大. Again, this is great to know if you want to really understand Chinese characters in themselves, but it’s definitely not needed if your goal is just to be able to recognise the character. It is possible to delve too deep sometimes, which I discussed in more detail here:

5 levels of understanding Chinese characters: Superficial forms to deep structure

So, not everything is as it seems. This is by definition hard to know, and most native speakers don’t know that 彳 is unrelated to 亻, that 龵 in 看 is not actually a hand, and that 熊 has nothing to do with fire!

Learning more about Chinese characters and character components

So how do you know what something actually means? How do you know when 灬 is not 火, when 龵 is not 手, and that 彳 is unrelated to 亻? You ask the experts, of course! Outlier Linguistics offers a dictionary that makes all this information easily accessible on your phone. I highly recommend this resource and you can check out my full review here:

If you want my best advice about learning Chinese characters, check out my guide here: My best advice on how to learn Chinese characters

https://www.hackingchinese.com/my-best-advice-on-how-to-learn-chinese-characters/

2 comments

Interesting article! I think there might be a typo here: “most native speakers don’t know that 彳 is in fact the left half of 行”. Based on context, do you mean “is NOT in fact”?

No, I think I meant what I wrote, but I can see that it’s not worded very clearly! I think that most native speakers think of 彳 as 双人旁, and that very few would connect it to 行. Obviously, they know that the left part of 行 is also 彳, but I meant that the connection from 彳 to 行 is not something the average person knows. Does that make what I meant clearer? I changed that part of the sentence to “most native speakers don’t know that 彳 is unrelated to 亻”, which is more consistent with how the other examples are treated and in practice means the same thing.