Learning to read and write Chinese characters is a unique challenge. To be able to read normal text in Chinese, you need to know around 3,500 characters, even though the exact number depends on what you are reading, and there’s more to reading than just knowing characters. It should be clear to anyone that this is not an alphabet, then, and that Chinese characters do not represent sounds the way our letters do.

Learning to read and write Chinese characters is a unique challenge. To be able to read normal text in Chinese, you need to know around 3,500 characters, even though the exact number depends on what you are reading, and there’s more to reading than just knowing characters. It should be clear to anyone that this is not an alphabet, then, and that Chinese characters do not represent sounds the way our letters do.

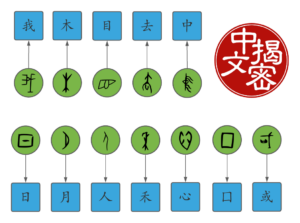

That doesn’t mean that Chinese characters are pictures, though, even if it is true that many basic characters started out as such. It’s not too hard to imagine that 木 (mù) shows a tree, or that 人 (rén) is a sideways view of a person.

The letters in our alphabet had similar origins, but we only use them to represent sounds these days. In contrast, there’s nothing in 木 or 人 that hints at their pronunciation. You just have to learn that, just like you need to learn that the numeral 6 is read “six” and that $ is read “dollar”, you can’t know that by just looking at the written form.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcast, Overcast, Spotify and many other platforms!

Chinese characters are not pictures

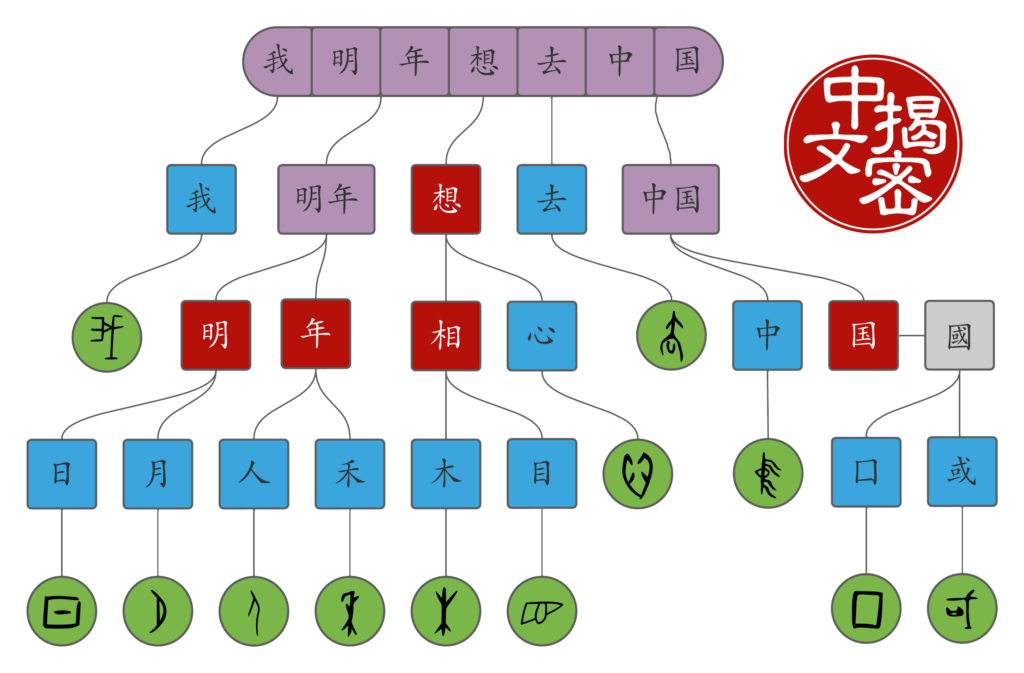

Most characters are not simple pictures, though. Instead, they are combinations of other characters, which means that a very large majority of those 3,500 characters we might be our long-term goal aren’t actually unique symbols you need to memorise, but are rather combinations of a smaller set of components.

To continue our example above, the character for “to rest”, 休 (xiū), shows a version of person 人 (rén) next to a tree 木 (mù), suggesting the idea of resting in the shade of a tree. Another example is putting two bright objects, namely the sun 日 (rì) and the moon 月 (yuè) next to each other to form the character for “bright”, 明 (míng). There are also other types of compounds we will get to later.

To learn to read or write, you need to go beyond individual characters, though, because most words in modern Chinese consist of two characters, not combined into a new character like 休 (xīu) above, but just written next to each other. For example, the word for “China”, 中国 (zhōngguó) consists of two characters: the characters for “middle”, 中 (zhōng) and “country; kingdom”, 国 (guó).

Other cases are less obvious, such as “next year”, 明年 (míngnián), consisting of “bright”, 明 (míng) and “year”, 年 (nián). Note that in Chinese, there’s an almost perfect 1:1 correspondence between characters and syllables, so a two-syllable word will be written with two characters.

Thus, learning to read and write Chinese characters is done on several levels. These are not steps where you have to complete one before advancing to the next, but parallel processes all learners work with all the time when learning Chinese.

In order to learn to read and write, you need to:

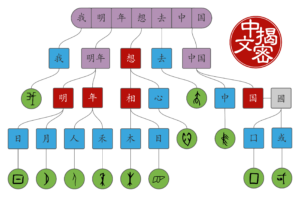

Learn basic characters, such as 木 (mù) “tree”, 人 (rén) “person”, 日 (rì) “sun” and 月 (yuè) “moon”, which can sometimes be used on their own, but also function as components in compound characters. In the image above, the basic characters are shown in blue, with their original forms in green (more about this later). This is covered in the next article in this series: The building blocks of Chinese, part 2: Basic characters, components and radicals.

Learn basic characters, such as 木 (mù) “tree”, 人 (rén) “person”, 日 (rì) “sun” and 月 (yuè) “moon”, which can sometimes be used on their own, but also function as components in compound characters. In the image above, the basic characters are shown in blue, with their original forms in green (more about this later). This is covered in the next article in this series: The building blocks of Chinese, part 2: Basic characters, components and radicals.- Learn to combine basic components into compound characters, such combining 木 and 人 into 休 (xiū) “to rest”, or combining 日 and 月 into 明 (míng) “bright” . There are many different ways this can be done, we’ll explore the most important ones in the next. In the image, compound characters are shown in red. We’ll go through compound characters in detail here in part 3: Compound characters and part 4: Learning and remembering compound characters.

- Learn to combine individual characters into words, such as 中国 (zhōngguó) “China” or 明年 (míngnián) “next year”. Compound words like these are often more straightforward than compound characters, but as you can see, they are not always as easy as the word for China. We will still look at some useful strategies to learn words more effectively. In the image, words are shown in purple; more about this in part 5: Making sense of Chinese words as well as part 6: Learning and remembering compound words

- Learn thousands of characters and words efficiently and effectively, which brings in long-term retention and strategies for avoiding mixing characters up, which becomes increasingly harder the more you learn. We will discuss this in the last instalment: The building blocks of Chinese, part 7: Mastering Chinese characters as an adult.

Here’s a list of all the articles in the series:

- Part 1: Chinese characters in a nutshell

- Part 2: Basic characters and character components

- Part 3: Compound characters

- Part 4: Learning and remembering compound characters

- Part 5: Making sense of Chinese words

- Part 6: Learning and remembering compound words

In this series, I will go through the above processes with the goal of explaining how written Chinese works and how to approach characters as a student. I will try to stick to the most important things, but will provide links to more reading for those who want to know more. When you’ve finished this series of articles, you should know not just how characters work, but also what characters to learn and how to go about it!

If you prefer to watch a video course talking about these concepts in much more detail, I invested a lot of time in creating a video course about Chinese characters for beginners over at Skritter, where you can also practise writing the characters. Accessing the course requires a subscription, but you can get 10% off by using this link when signing up on the website. If you want to stick to free stuff, this article and the rest in this series are completely free, as are more than 400 other articles here on Hacking Chinese! Here’s a trailer for the character course:

Learning Chinese characters as an adult foreigner

Before we get into learning characters, though, I want to say some general things about learning written Chinese and some things you should keep in mind when reading the rest of the series.

First of all, should you learn the spoken and written language in parallel, learning to write what you can say and to read what you can listen to? The short answer is that it’s probably best to delay learning the written language a bit to reduce the cognitive load and focus on learning things like pronunciation and tones properly first. Delaying characters have no serious long-term downsides, but delaying pronunciation can be really bad. Of course, you can and many students do learn the spoken and written language in parallel, but letting the written language lag behind is beneficial. I wrote more about this here:

Should you learn to speak Chinese before you learn Chinese characters?

Learning written Chinese: Building a house from the bottom up

In this series, we’re going to look at the Chinese writing system from the bottom up. That means that we’re going to start with the smallest building blocks, then move on to more complex compounds, then compounds of compounds and so on. The goal is to teach you how the writing system works.

The real problem you face when reading Chinese is the opposite, though, where the house is already finished and you need to break it down in order to make sense of a text. However, the goal here is to explain the writing system in general, rather than understanding a specific text, and then a bottom-up explanation makes more sense for most learners.

The best way to learn to read is to read

It’s important to not go on tilt and invest all your time into learning individual characters. The goal is to learn to read and/or write Chinese, not to memorise vocabulary for its own sake. Both reading and writing are very complex processes that can’t be reduced to just a number, even if it is very tempting.

What I’ve found works best, and is what most research into both reading and vocabulary acquisition supports, is to combine input (reading and listening) with targeted vocabulary practice. Input here should be comprehensible, meaning that you should be able to understand as much as possible. As a beginner, you won’t be able to find texts you can read without lots of support, but do your best to find easy texts. Using one or more textbooks is fine, but you can also find lots of free reading resources here: The 10 best free Chinese reading resources for beginner, intermediate and advanced learners

The 10 best free Chinese reading resources for beginner, intermediate and advanced learners

Vocabulary practice can involve many things, but here I include anything that relates to characters and words that isn’t directly linked to practical communication. For example, learning about the origin of a Chinese character or the composition of a compound can make it easier to remember, but looking things like that up doesn’t count as reading practice. Reading this series of articles doesn’t count as reading practice either, but my hope is that it will boost your learning significantly by making learning meaningful, which has been shown over and over to be essential for learning in general.

Reading, typing and handwriting: What’s your goal?

It’s also important to understand that the difference between knowing how to read Chinese and being able to write it by hand is much bigger than in English. Reading requires you to recognise characters in context, but writing by hand requires you to actively recall every detail of every character. Typing usually works by writing how something is pronounced and then making sure the input method chooses the right characters (which it usually does), so it’s more akin to reading than writing by hand.

This raises the question of whether you really need to learn to write by hand at all, as it takes much more effort and is unlikely to be of much practical use. The short answer is that you probably should learn to write the most common characters by hand, if for no other reason than getting a good grasp of how characters work, but that in the long run, most students would be okay with just reading and typing. If you feel that this answer is not enough, you can read more in this article: Is it necessary to learn to write Chinese characters by hand?

So the answer is that it depends on your goals for learning, but that you shouldn’t feel compelled to write by hand everything you can read. If you’re a teacher or want to read more about why it’s so bad to force all students to write everything by hand, please check Chinese character learning for all students.

What you don’t need to learn: Traps to avoid when learning Chinese characters

Most people will only tell you what to learn, but sometimes knowing what not to learn can be even more useful and save you a lot of time and frustration. Here is a short list of things related to Chinese writing that you can safely save for later or avoid completely:

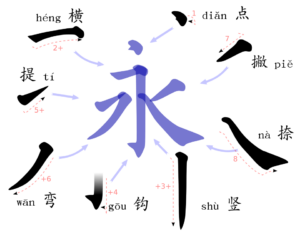

Don’t waste time learning the names of all the strokes, especially not combinations of strokes. If your teacher uses them when writing and you learn them by pure exposure, fine, but you should not spend extra time learning the names. Don’t focus on smaller things than basic characters and functional components (see the next article in this series). Read more about stroke names here: Should you learn the names of the strokes in Chinese characters?

Don’t waste time learning the names of all the strokes, especially not combinations of strokes. If your teacher uses them when writing and you learn them by pure exposure, fine, but you should not spend extra time learning the names. Don’t focus on smaller things than basic characters and functional components (see the next article in this series). Read more about stroke names here: Should you learn the names of the strokes in Chinese characters? Don’t obsess over theory. In this series, I will teach you how characters work and how to learn about the origins of specific characters and their development. Such information is only useful if it helps you understand and remember. If you want practical knowledge, the overwhelming majority of your time should be spent in close engagement with the language, not theoretical explanations in English. A valid method for learning is one that is closely connected to real-world communication.

Don’t obsess over theory. In this series, I will teach you how characters work and how to learn about the origins of specific characters and their development. Such information is only useful if it helps you understand and remember. If you want practical knowledge, the overwhelming majority of your time should be spent in close engagement with the language, not theoretical explanations in English. A valid method for learning is one that is closely connected to real-world communication. Don’t clump reviews together when writing. Many people, including many teachers, will tell you to write characters dozens or even hundreds of times in a row, and might even claim that this is the only way to learn. However, while doing so will improve your penmanship, writing the same thing over and over again is really inefficient for long-term retention. Spread the reviews out over time! We’ll return to this later in this series. You can also have a look at this article: Spaced repetition software and why you should use it.

Don’t clump reviews together when writing. Many people, including many teachers, will tell you to write characters dozens or even hundreds of times in a row, and might even claim that this is the only way to learn. However, while doing so will improve your penmanship, writing the same thing over and over again is really inefficient for long-term retention. Spread the reviews out over time! We’ll return to this later in this series. You can also have a look at this article: Spaced repetition software and why you should use it. Don’t worry if your handwriting is ugly. How nice your characters look depends a lot on how good you are at writing by hand in your own language, but you don’t need to care about aesthetics when you start out. You should instead focus on problems that might make a native speaker misunderstand what you wrote. If you really want to learn to write neatly, here are some suggestions: How to improve your Chinese handwriting.

Don’t worry if your handwriting is ugly. How nice your characters look depends a lot on how good you are at writing by hand in your own language, but you don’t need to care about aesthetics when you start out. You should instead focus on problems that might make a native speaker misunderstand what you wrote. If you really want to learn to write neatly, here are some suggestions: How to improve your Chinese handwriting.- Don’t feel too daunted by the journey ahead, because even though it might feel like learning thousands of characters is almost impossible, it becomes easier the more you learn. Also, it’s not the case that you need thousands of characters before you can read anything. Every character you learn and every hour you spend reading increases your reading ability! I’m not saying that becoming literate is easy, just that it can be done with some persistence and effort.

These points all came from this article: How to not teach Chinese characters to beginners: A 12-step approach.

We’ve now reached the end of this introductory article. In the next article in this series, we will start by looking at basic characters and components. As we shall see, learning a few hundred fairly simple characters will unlock the Chinese writing system and make it possible to learn thousands of characters. Read the next article here:

https://www.hackingchinese.com/the-building-blocks-of-chinese-part-2-basic-characters-components-and-radicals/

3 comments

Olle,

simply: excellent!!!

Great thanks for all your efforts to help,

Michael

Just to say THANK YOU for all the content. Discovering your site/ podcast has been like discovering a new world! So grateful for the generosity and the amount of info you share. Loving this journey of learning Mandarin!

Hi Sonia! I’m so happy to hear you say that! I know many people read and listen to Hacking Chinese, but not everybody tells me what they think. My main motivation for doing all this is of course to help students, so hearing that you find the content helpful makes it easier to write the next article and record the next podcast episode!