Tones pose a major challenge for most learners of Chinese. What are tones? How important are they? How do you learn to hear and say them? What are the best resources for learning tones?

Tones pose a major challenge for most learners of Chinese. What are tones? How important are they? How do you learn to hear and say them? What are the best resources for learning tones?

Tones are changes in pitch (tone height) that are used to differentiate words in Mandarin, much like vowel length is in English (compare “bid” and “bead”). They are an integral part of the language and can’t be ignored more than vowel length can in English.

Learning to hear and pronounce tones as an adult takes time but with the right methods and resources, you can do it! This article is a guide to learning tones for students of Chinese as a second language.

A guide to learning tones in Mandarin

This article is meant to gather the many articles I have written on the subject of learning tones, providing an overview for students and teachers. To keep this article readable, I will summarise the main points from other articles and link to further reading for those who want it.

This article is divided into several sections:

- What are tones? How do tones work in Mandarin?

- How important are tones when learning Mandarin?

- How do I learn to hear and say Mandarin tones?

- Resources for learning tones

- Conclusion

- Comments

Hacking Chinese Tones: Speaking with Confidence

Before we get to the main parts of this article, I’d like to mention that I offer a course that will help you figure out tones, either as a beginner or as a more advanced student struggling with tones or other aspects of Mandarin pronunciation. You can check it out here: Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence

The rest of the advice on this page is for free, however, including all the articles I link to, so the course is mostly for those who want a video course covering everything you need to know about Chinese pronunciation.

1. What are tones? How do tones work in Mandarin?

In this section, I will explain what tones are and how they work in Mandarin. I’ve written this explanation for complete beginners and you need no prior knowledge to make sense of it. I will use text, sound, diagrams and links to further reading to help you make sense of tones! If you have any questions, feel free to leave a comment below the article!

In this section, I will explain what tones are and how they work in Mandarin. I’ve written this explanation for complete beginners and you need no prior knowledge to make sense of it. I will use text, sound, diagrams and links to further reading to help you make sense of tones! If you have any questions, feel free to leave a comment below the article!

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode #183:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

1.1 Tones are differences in pitch that are used to differentiate words in Mandarin

Tones are differences in pitch that change the meaning of a spoken syllable. For example, in Mandarin, the syllable mā, with a high, flat tone, means “mother”, but the same syllable with a low or dipping tone, mǎ, means “horse”.

This might lead your thoughts to intonation, which is also about differences in pitch. For example, when someone asks if you want something hot to drink, they might say “Tea?” with a rising pitch, indicating a question, but when you answer a question about what you want to drink, you might say “Tea!” with a falling pitch, probably followed by a “please” for politeness sake.

However, tone and intonation are two different things. Tones are about the basic meanings of words. If you change the tone, you change the word, so if you say mā instead of mǎ, you change the word from “mother” to “horse”. This is not the same as intonation, because regardless of what pitch you use when you say “tea” in English, it still refers to the same hot beverage; it doesn’t suddenly mean something completely different. In Mandarin, it does!

Still, intonation can be a useful analogy, because a one-word question in English, such as “Tea?”, is quite similar to a rising tone in Chinese, such as in má, meaning “hemp”. A firm statement in English has a falling tone, not unlike the falling tone in Chinese, such as in mà, meaning “scold”.

It’s worth noting that Mandarin has intonation too, but it’s unnecessarily complicated to talk about tone and notation at the same time, so if you’re new to learning the language, focus on tones first!

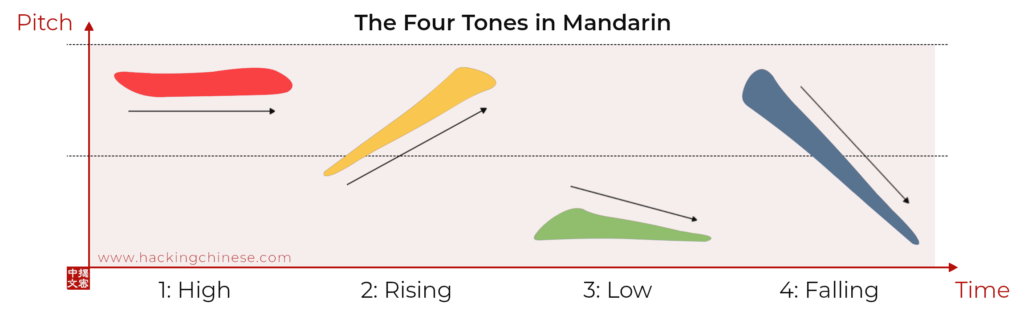

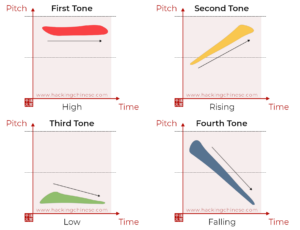

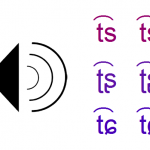

1.2 Mandarin has four tones: high, rising, low, and falling, plus a neutral tone

Mandarin has four different tones, usually numbered from one to four (click the link to hear the word):

The first tone is high, as in mā, “mother”. To beginners, it often sounds a bit unnatural, both because it’s quite high and because it’s flat. In English, we normally don’t speak like this, but it might be similar to the sound you make when opening your mouth and saying “aah” at the dentist’s. Identifying this tone usually does not cause too much trouble because it stands out as having a steady pitch, but pronouncing it can be hard because it sounds unnatural at first, especially if you have several first tones in a row or at the end of a statement.

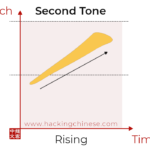

The first tone is high, as in mā, “mother”. To beginners, it often sounds a bit unnatural, both because it’s quite high and because it’s flat. In English, we normally don’t speak like this, but it might be similar to the sound you make when opening your mouth and saying “aah” at the dentist’s. Identifying this tone usually does not cause too much trouble because it stands out as having a steady pitch, but pronouncing it can be hard because it sounds unnatural at first, especially if you have several first tones in a row or at the end of a statement. The second tone is rising, as in má, “hemp”. As mentioned, this tone sounds like a single-word question in English. It starts in the middle of the pitch range and rises to the top. The most common issues students have with the second tone are that they don’t rise early enough and that they start too high, which means that there’s not enough room to rise. Beginners also might feel it’s strange to rise like this when you aren’t asking a question. Read more here: Learning the second tone in Mandarin Chinese.

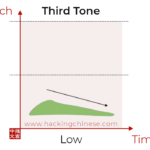

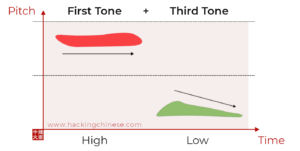

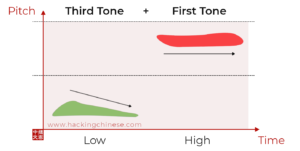

The second tone is rising, as in má, “hemp”. As mentioned, this tone sounds like a single-word question in English. It starts in the middle of the pitch range and rises to the top. The most common issues students have with the second tone are that they don’t rise early enough and that they start too high, which means that there’s not enough room to rise. Beginners also might feel it’s strange to rise like this when you aren’t asking a question. Read more here: Learning the second tone in Mandarin Chinese. The third tone is low, as in mǎ, “horse. The third tone is traditionally taught as a dipping tone, mǎ, even though it’s very rarely a dipping tone in reality. Unlike the other tones, the third tone changes its pitch contour depending on the following syllable, so in front of another third tone, it turns into a rising tone. In front of any other tone, it’s just a low tone. For details about how this works, along with examples and illustrations, please read Learning the third tone in Mandarin Chinese.

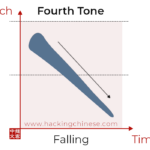

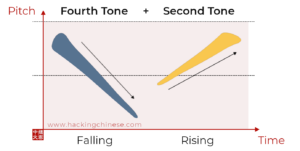

The third tone is low, as in mǎ, “horse. The third tone is traditionally taught as a dipping tone, mǎ, even though it’s very rarely a dipping tone in reality. Unlike the other tones, the third tone changes its pitch contour depending on the following syllable, so in front of another third tone, it turns into a rising tone. In front of any other tone, it’s just a low tone. For details about how this works, along with examples and illustrations, please read Learning the third tone in Mandarin Chinese. The fourth tone is falling, as in mà, “to scold”. As mentioned, it’s not unlike a firm statement in English, such as when saying “No!” to a child about to do something they shouldn’t. However, it’s not louder than the other tones, so don’t be too firm! Start at the top of your pitch range and fall to the bottom, but don’t hurry. Some students mix up the second and fourth tones because they both change pitch, albeit in the opposite direction, but this usually goes away quickly. Start high, end low, but don’t hurry and don’t shout!

The fourth tone is falling, as in mà, “to scold”. As mentioned, it’s not unlike a firm statement in English, such as when saying “No!” to a child about to do something they shouldn’t. However, it’s not louder than the other tones, so don’t be too firm! Start at the top of your pitch range and fall to the bottom, but don’t hurry. Some students mix up the second and fourth tones because they both change pitch, albeit in the opposite direction, but this usually goes away quickly. Start high, end low, but don’t hurry and don’t shout!

Learning tones in isolation is not too hard, but nailing them in sentences while speaking will take time to master. We will talk more about how to learn tones later in this article, but my advice is that as soon as you think you’ve got single tones down, put all your energy into truly mastering tone pairs.

1.3 The neutral tone lacks a pitch of its own and instead borrows it from its surroundings

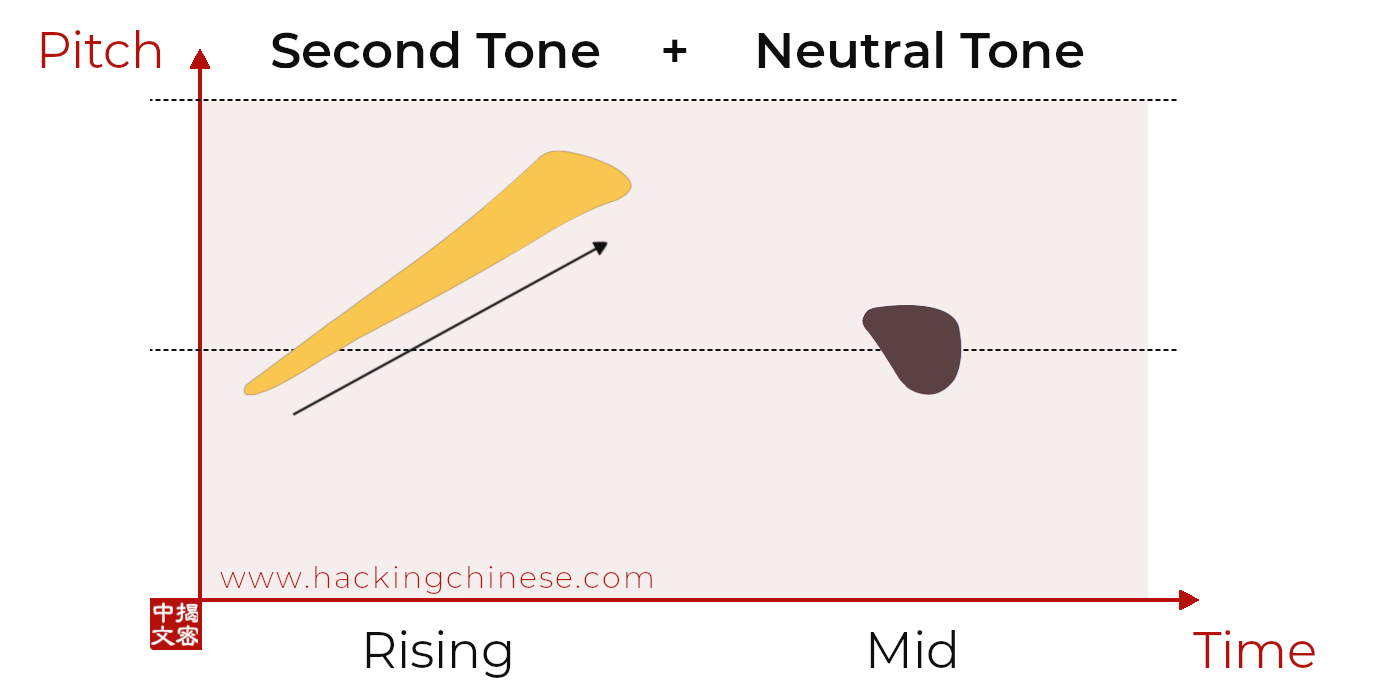

Apart from the four basic tones, Mandarin also has a neutral tone, which is not a fifth tone, but rather an unstressed syllable that has no inherent tone of its own. Instead, it borrows its pitch from elsewhere, usually the preceding syllable or intonation. It follows then that it’s hard to pronounce a neutral tone on its own, so here’s an example in a word: júede, “feel; think”. The second syllable in that word is not stressed and has a neutral tone.

Apart from the four basic tones, Mandarin also has a neutral tone, which is not a fifth tone, but rather an unstressed syllable that has no inherent tone of its own. Instead, it borrows its pitch from elsewhere, usually the preceding syllable or intonation. It follows then that it’s hard to pronounce a neutral tone on its own, so here’s an example in a word: júede, “feel; think”. The second syllable in that word is not stressed and has a neutral tone.

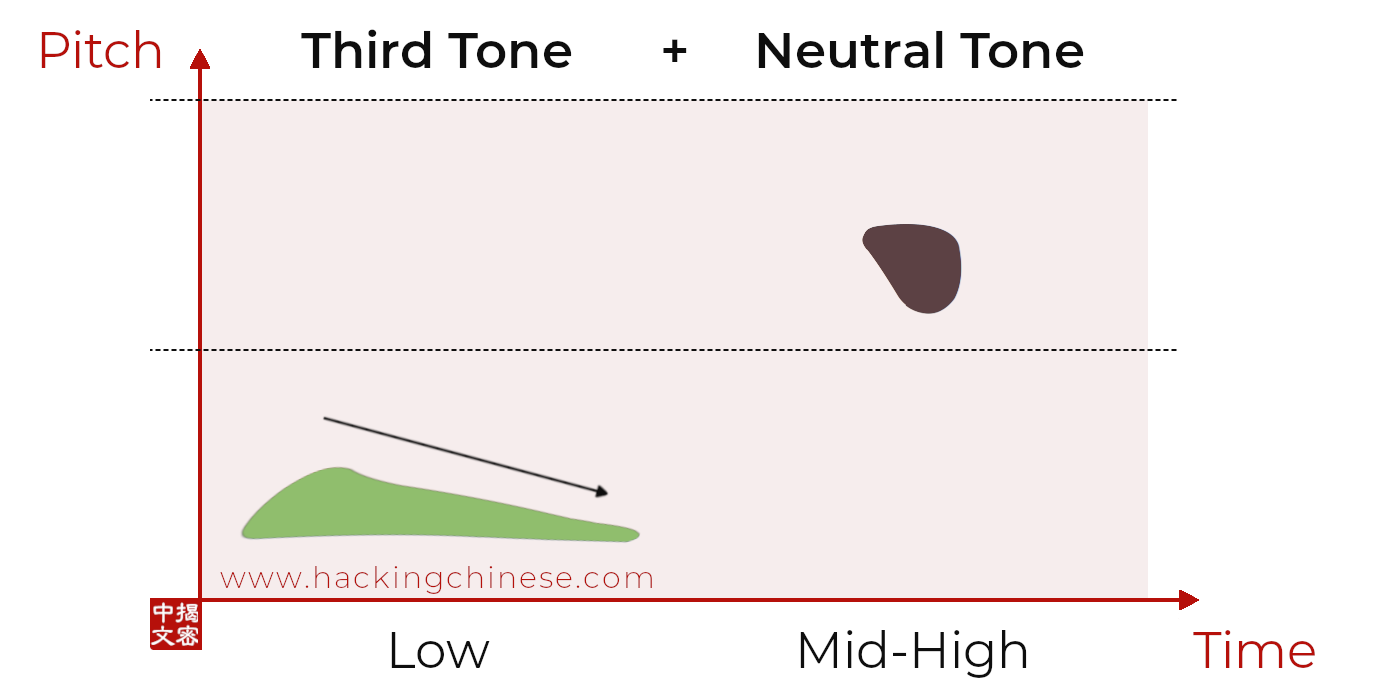

By default, the neutral tone is pronounced with a slightly lower pitch than the preceding syllable. If you listen to the recording above and the accompanying diagram, the neutral tone is lower than the end of the rising tone that comes before it.

By default, the neutral tone is pronounced with a slightly lower pitch than the preceding syllable. If you listen to the recording above and the accompanying diagram, the neutral tone is lower than the end of the rising tone that comes before it.

This is true after the first tone and fourth tone, too, although after the fourth tone, you can’t go much lower, so it’s just low. The only exception is the third tone, after which a neutral tone is pronounced with a high pitch. Listen: yǐzi, “chair”.

Note that the reason the neutral tone is not a fifth tone is that the underlying tone of the syllable itself does not matter. For example, the de in juéde is originally a rising tone, but not here. No matter what the original tone is, a neutral tone is pronounced the same in a given context.

Read more: Learning the neutral tone in Mandarin

1.4 Tones in Mandarin sometimes change depending on the context

A challenge when learning tones is that they’re rarely pronounced one at a time and that there are several rules you need to learn to master how tones change depending on the context. We already saw that the third tone changes to a rising tone in front of another third tone, so kěyǐ, “can”, is in practice pronounced kéyǐ, although it’s never written like that. Listen!

A challenge when learning tones is that they’re rarely pronounced one at a time and that there are several rules you need to learn to master how tones change depending on the context. We already saw that the third tone changes to a rising tone in front of another third tone, so kěyǐ, “can”, is in practice pronounced kéyǐ, although it’s never written like that. Listen!

Another example of tone change (called “tone sandhi” in linguistics) is that bù, “not”, and yī, “one”, are both pronounced with a rising tone in front of a falling tone. This might sound unnecessary, but it makes it easier to pronounce these words in context, which happens often because they are so common. For full details about how this works, please read Obligatory and optional tone change rules in Mandarin.

Fortunately, these are the only cases that you have to learn. In other Chinese dialects, tone sandhi is very complicated, so if you think this section gave you a headache, pity those who are trying to learn Cantonese or Hokiien!

Still, I should mention that other tone changes in Mandarin happen quite naturally and that you don’t need to worry about them as a beginner or even an intermediate student. Those are also covered in the article about tone change rules if you are curious!

1.5 There are many ways to write down the tones in Mandarin

By far the most common way to write the tones in Mandarin is as I have done throughout this article, i.e. as diacritic marks above the main vowel: mā, má, mǎ, mà. However, it’s good to be aware that there are other ways of writing down the tones that might be more useful in some cases.

A problem with using diacritic marks is that they only roughly approximate the pitch. If you want to specify how a fourth tone is pronounced without drawing a diagram, you can use tone numerals, which indicate pitch on a scale from 1 to 5, with 1 being the lowest and 5 the highest. The word zhōngwén, “Chinese”, would be written zhong⁵⁵wen³⁵, enabling you to see that it’s a high flat tone (55) followed by a rising tone that starts in the middle and rises to the top (35).

Another popular option is to use colour to mark tones, which can be combined with either method mentioned above: zhōngwén or zhong⁵⁵wen³⁵, or even with Chinese characters directly: 中文. This method can be practical, but considering that there are many different colour schemes, it might hurt more than it helps! Read more in Does using colour to represent Mandarin tones make them easier to learn?

Another popular option is to use colour to mark tones, which can be combined with either method mentioned above: zhōngwén or zhong⁵⁵wen³⁵, or even with Chinese characters directly: 中文. This method can be practical, but considering that there are many different colour schemes, it might hurt more than it helps! Read more in Does using colour to represent Mandarin tones make them easier to learn?

There are other, less common ways of writing tones, including using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), tonal spelling and others. For an overview, including advice for students, please refer to 7 ways to write Mandarin tones.

2. How important are tones when learning Mandarin?

Tones in Mandarin are roughly as important as vowels. This means that you can still be understood in some situations even if you use the wrong tones, but it means that you can no more ignore tones than you can ignore vowels in English. If you already consider learning tones essential, you can skip this section and continue reading about how to learn tones instead. If you’re not convinced or would like to read more about why other people are not convinced, the rest of this section is for you.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode #184:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

2.1 Learning tones in Mandarin is not optional

If your native language is not tonal, which is true for Indo-European languages in general, including English, it’s natural to doubt the importance of tones. Your teacher might tell you that tones are important and I have already mentioned that tones are and I just said that tones are as important as vowels, but as a student, it’s hard to feel the importance of tones. This is especially true if you don’t hear the tones.

If your native language is not tonal, which is true for Indo-European languages in general, including English, it’s natural to doubt the importance of tones. Your teacher might tell you that tones are important and I have already mentioned that tones are and I just said that tones are as important as vowels, but as a student, it’s hard to feel the importance of tones. This is especially true if you don’t hear the tones.

Tones are important, however. If you neglect tones when you start learning Mandarin, you will regret it later. I have studied, taught and researched Mandarin for well over fifteen years now, and if you’re willing to take my word for it, just accept that tones are important, even if you can’t feel it. I have nothing to gain from trying to convince you that they are important if they weren’t. You don’t need to take just my word for it: I have so far never met an advanced learner of Mandarin as a second language who claims that tones are not important.

Moving beyond experience, I haven’t read any research that claims that tones are not important either. There is a lot of research about how tones or the absence of tones influence communication in tonal languages, however. Generally speaking, it’s possible to understand spoken Mandarin even when the speaker makes mistakes with tones, or even when tones are removed entirely.

This is not surprising, however, and the same thing can be said about vowels, but nobody would take this to mean that a learner of English can ignore vowels. That would be ludicrous, and ignoring tones in Mandarin is bad for the same reason.

The reason people can understand spoken Mandarin without perfect tones is that when processing language, we use all available information and rely heavily on context. You can understand spoken English even if all vowels are replaced by the same sound (see below), and many written languages, such as Hebrew, have optional vowels and are still readable.

Let’s talk more about the role of context!

2.2 Beginner learners of Mandarin tend to underestimate the importance of tones

Doubting the importance of tones is natural and quite common among students, especially if you can’t hear the tones yourself. You might also have noticed that people might understand you even if you make many mistakes with tones, making you doubt the importance of tones. Let’s dig deeper into why some students feel that tones are not as important as everybody claims.

I think there are three main reasons for this:

Context plays a bigger role in listening comprehension than most people think. You can be understood in any language while making mistakes with pronunciation, as long as the listener can use context to figure out what you mean. Beginners incorrectly conclude that tones, or accuracy in general, are not important, but that’s only because most things they say are highly predictable and can be easily guessed based on the context. For more about context in listening comprehension, see Beyond tīng bu dǒng, part 3: Using what you already know to aid listening comprehension in Chinese.

Context plays a bigger role in listening comprehension than most people think. You can be understood in any language while making mistakes with pronunciation, as long as the listener can use context to figure out what you mean. Beginners incorrectly conclude that tones, or accuracy in general, are not important, but that’s only because most things they say are highly predictable and can be easily guessed based on the context. For more about context in listening comprehension, see Beyond tīng bu dǒng, part 3: Using what you already know to aid listening comprehension in Chinese.- Teachers are extremely good at understanding Chinese spoken by beginners. They have listened to hundreds or thousands of students mangle tones and can figure out what you mean even if your pronunciation is horrendous. Your teacher also knows which words you know and which sentence patterns you’re able to use. Thus, the fact that your teacher, or someone else who knows you well, can understand what you say without tones, does not mean that other people will be able to.

Students often don’t hear the tones. Learning to hear tones as an adult takes time. This leads some students to believe that native speakers don’t use tones when they speak naturally and that the best approach to sound fluent is just to speak faster. This is wrong, however. Native speakers certainly use tones when speaking, but they will not pronounce them as clearly as your teacher or the audio that comes with your textbook. Pronunciation also tends to change in context, especially as people speak faster, but this happens in all languages. We will talk more about how to learn to hear tones in the section about how to learn tones below, but if you want to read more right now, check: Learning to hear the sounds and tones in Mandarin.

Students often don’t hear the tones. Learning to hear tones as an adult takes time. This leads some students to believe that native speakers don’t use tones when they speak naturally and that the best approach to sound fluent is just to speak faster. This is wrong, however. Native speakers certainly use tones when speaking, but they will not pronounce them as clearly as your teacher or the audio that comes with your textbook. Pronunciation also tends to change in context, especially as people speak faster, but this happens in all languages. We will talk more about how to learn to hear tones in the section about how to learn tones below, but if you want to read more right now, check: Learning to hear the sounds and tones in Mandarin.

The first reason above about context is the most important one, so let’s turn to that next.

2.3 Tones become more important as you say more interesting things

As mentioned above, you can say basic things in English and be understood using only a single nowel sound:

If I wiri ti spiik Inglish with iii ising inli thi viwil “i”, iii wiild still indirstind whit I miint.

It would be harder to understand than if I used the correct vowels, but it would be understandable. This is because not all information in an utterance is carried by the vowels, we also have consonants, and in most cases, your knowledge of English vocabulary will let you know that “viwil” probably means “vowel”. You can also use your knowledge of English grammar to figure out that “whit” is actually “what” because the latter makes sense in that position in the sentence while the former does not.

This is what it’s like to speak Mandarin without tones. People will be able to understand what you say, provided they can guess what you mean based on context. However, I think you’d agree that just because I can speak English using only the vowel “i”, it would be terrible advice for a learner of English to do so. Ignoring tones when learning Chinese is an equally terrible idea.

For more about why tones might feel less important than they are, see The importance of tones is inversely proportional to the predictability of what you say.

The importance of tones is inversely proportional to the predictability of what you say

2.4 Why tones in Mandarin matter more than you think

Even though it’s true that native speakers might understand you without using correct tones, vowels or consonants, it’s safe to say that doing so is not easy. In addition, learners of Chinese as a second language don’t only have problems with tones, but also with word choice, sentence structure and much more, which means that problems add up, resulting in a communication breakdown.

As your Mandarin improves, you will also want to say more complex and less predictable things, and then tone accuracy starts to matter a lot. As an advanced student myself, it’s not uncommon that one missed tone in an otherwise perfect sentence results in a blank stare and a request to repeat what I said. This is of course not limited to my own experience, but is quite common.

Finally, if your goal is to just barely be understood in clear contexts, you can ignore lots of things, not just tones. I assume that if you’ve read this far in this guide, you care about your ability to communicate more than that. I’ve written more about why clear pronunciation matters here: Two reasons why pronunciation matters more than you think.

2.5 Even a single tone mistake can lead to confusion

As we have seen, the importance of tones increases as the complexity of what you want to express increases and the listener is not able to predict what you’re going to say. This means that at an advanced level, tones sometimes feel subjectively more important than they do at a beginner level! However, this is mostly an illusion created by the dependence on the context discussed above.

There are many cases where even a single tone mistake can lead to confusion, regardless of your language level in general. This happens when two words are pronounced with the same initial and final, but with a different tone, and those words are also interchangeable in the sentence they appear in. This makes the listener unable to rely on the content to guess, leading to confusion.

Here are a few examples:

- mǎi/mài, “to buy”/”to sell”, 买/卖 (買/賣),

- nǎlǐ/nàlǐ, “where”/”there” , 哪里/那里 (哪裡/裡)

- chòu/chǒu, “smelly”/”ugly”, 臭/丑 (臭/醜)

- bēizi/bèizi, “cup; glass”/”quilt”, 杯子/被子 (杯子/被子),

- huā/huà, “flower”/”painting”, 花/画 (花/畫)

For explanations of each and many more examples, continue reading Tone errors in Mandarin that actually can cause misunderstandings:

Tone errors in Mandarin that actually can cause misunderstandings

So, tones are important.

Learn them. Now!

But how?

3. How do I learn to hear and say Mandarin tones?

First and foremost, you can learn to both hear and say tones correctly as an adult learner of Mandarin. Anyone who says it’s impossible, that it requires musical aptitude or some other rare talent is probably wrong. This doesn’t mean that it’s easy or that you are guaranteed success regardless of what approach you take, so in this section, we’ll delve deeper into how to learn tones effectively.

Tune in to the Hacking Chinese Podcast to listen to the related episode #185:

Available on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, YouTube and many other platforms!

This section is divided into several parts:

- Learning to hear the tones

- Learning to say the tones

- The importance of tone pairs

- How to remember tones

- Identifying and fixing problems with tones

- Questions and answers about tones

3.1 Learning to hear the tones in Mandarin

As babies, we can hear all possible speech sounds, but as our brains adapt to the languages around us, we gradually lose the ability to distinguish sounds that are not important. Thus, growing up with English, you maintain the ability to hear the difference between “bid” and “bead”, but since tone is not used to distinguish words in English, your ability to hear them will fade out.

As babies, we can hear all possible speech sounds, but as our brains adapt to the languages around us, we gradually lose the ability to distinguish sounds that are not important. Thus, growing up with English, you maintain the ability to hear the difference between “bid” and “bead”, but since tone is not used to distinguish words in English, your ability to hear them will fade out.

In contrast, a person growing up with Mandarin doesn’t need to differentiate “bid” and “bead”, so will lose that ability, but since tones are an integral part of their native language, they identifying them will remain natural to them.

In the literature, this is called “categorical perception”, because it’s about sorting sounds into categories appropriate for the language in question. Learning to do this as an adult is hard, but not impossible. It requires extensive exposure to a wide variety of languages over time with prompt feedback. Thus, the most important thing you can do to learn to hear tones is to listen more. However, you need to be able to make the correct connections between spoken sound and intended tone, so putting on a TV show you don’t understand won’t help much.

There’s been a fair amount of research into learning to hear new speech sounds as an adult, and there seem to be two different methods that work:

High-variability training is when you are systematically exposed to the target sounds and given immediate feedback if you perceived them correctly or not. This has to be done across many different speakers to be effective. As part of a research project, I have created a free tone course that uses this approach to successfully help you identify the four basic tones in Mandarin.

High-variability training is when you are systematically exposed to the target sounds and given immediate feedback if you perceived them correctly or not. This has to be done across many different speakers to be effective. As part of a research project, I have created a free tone course that uses this approach to successfully help you identify the four basic tones in Mandarin.- Learning by exaggeration means that you work on your perception of tones with a tutor who exaggerates the differences for you in a way that allows you to identify the tones. For example, the first tone can be made very high, the low tone very low, and so on. This exaggerated pronunciation then gradually returns to a more normal way of speaking as you learn to keep the tones apart.

Learn more here: Learning to hear the sounds and tones in Mandarin.

How hard it is to learn to hear tones varies dramatically between individuals. I have taught hundreds of beginners over the years, and some of them seem to grasp tones in a matter of weeks, while some still struggle with basic tones after a semester. Most students fall somewhere in between.

There is one thing that matters more than anything else, however, and that is your ambition. If you think tones are important and invest time and energy into learning them, you will succeed. The students with the worst tones are often those who think it doesn’t matter or can’t be bothered to take pronunciation seriously.

3.2 Learning to pronounce the tones in Mandarin

Learning to hear and say the tones are connected. In general, it’s hard to be able to consistently pronounce something correctly if you can’t identify if what you say is correct or not. That doesn’t mean that you have to focus only on listening first, but note that more speaking practice is not always the solution. Successfully mastering Mandarin pronunciation rests on four pillars:

Listening is about connecting spoken sounds (including tones) to meaning and making sense of what someone says in Mandarin. Beyond that, there’s no specific way of listening that works better than others, so aim for variety and quantity. The more you listen, the better, and listening to different people speaking a lot is the best! Read more about how to listen here: 7 ideas for smooth and effortless Chinese listening practice.

Listening is about connecting spoken sounds (including tones) to meaning and making sense of what someone says in Mandarin. Beyond that, there’s no specific way of listening that works better than others, so aim for variety and quantity. The more you listen, the better, and listening to different people speaking a lot is the best! Read more about how to listen here: 7 ideas for smooth and effortless Chinese listening practice. Mimicking native speakers is by far the best way to learn pronunciation in general and tones in particular. It combines attentive listening to native speakers, producing sounds yourself, and comparing your output with the target audio. There are many ways of mimicking and they are all good for learning tones. I have described the method I think is most effective in great detail here, including with video: Improving your Chinese pronunciation by mimicking native speakers.

Mimicking native speakers is by far the best way to learn pronunciation in general and tones in particular. It combines attentive listening to native speakers, producing sounds yourself, and comparing your output with the target audio. There are many ways of mimicking and they are all good for learning tones. I have described the method I think is most effective in great detail here, including with video: Improving your Chinese pronunciation by mimicking native speakers. Theory can help you notice key features of tones. If you think the third tone is a dipping tone, you will struggle to understand how it works (it’s a low tone, as discussed above). If you have a basic understanding of how tones change in context, it will be easier both to understand and to pronounce them. Still, theory is not a substitute for listening and mimicking and can only offer limited benefits. Read more here: How learning some basic theory can improve your Mandarin pronunciation.

Theory can help you notice key features of tones. If you think the third tone is a dipping tone, you will struggle to understand how it works (it’s a low tone, as discussed above). If you have a basic understanding of how tones change in context, it will be easier both to understand and to pronounce them. Still, theory is not a substitute for listening and mimicking and can only offer limited benefits. Read more here: How learning some basic theory can improve your Mandarin pronunciation. Feedback is essential for learning tones. I’ve already mentioned that knowing if you heard a tone correctly is crucial for establishing the right tone categories, but it’s also essential for pronouncing tones yourself. It’s almost impossible to evaluate how good your pronunciation is without professional feedback or at least some way of checking systematically. Native speakers will typically praise your pronunciation regardless of how good it is. I offer a detailed pronunciation check-up as an optional add-on to my pronunciation course, but if that does not suit you, make sure you get feedback some other way. Read more here: How to get honest feedback to boost your Chinese speaking and writing.

Feedback is essential for learning tones. I’ve already mentioned that knowing if you heard a tone correctly is crucial for establishing the right tone categories, but it’s also essential for pronouncing tones yourself. It’s almost impossible to evaluate how good your pronunciation is without professional feedback or at least some way of checking systematically. Native speakers will typically praise your pronunciation regardless of how good it is. I offer a detailed pronunciation check-up as an optional add-on to my pronunciation course, but if that does not suit you, make sure you get feedback some other way. Read more here: How to get honest feedback to boost your Chinese speaking and writing.

If you want to read more about learning pronunciation, including tones, as a beginner, check How to learn Chinese pronunciation as a beginner.

You should also check out these two courses.

- Unlocking Chinese: The Ultimate Guide for Beginners covers everything you need to know about learning Mandarin as a beginner, including pronunciation and tones. If you want to dig deep, you should check out the pronunciation course instead, which works for both beginners and more advanced students.

- Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence is a full video course where I teach you everything you need to know about Mandarin pronunciation. As mentioned, there is also a feedback option if you want to either get feedback as you learn (beginners) or a thorough, systematic check-up of how far you’ve come (more advanced students).

3.3 Why you should focus on tone pairs

When approaching tones in Mandarin, it might seem chaotic. Sure, you have four basic tones and a neutral tone, and when you’ve learnt about them from a tutor, video or this article, they don’t seem that bad. In fact, most students learn to both hear and say the four basic tones rather quickly if they put some effort into them (and some do without putting in much effort either).

But then you start stringing together words into phrases, and the difficulty ramps up quickly. What seemed to be easy in isolation becomes a nightmare when combined with the complexity of words and sentences. How are you supposed to figure out what to say, choose the right words, and then also remember how the third tone changes and what the neutral tone is supposed to do in this specific case?

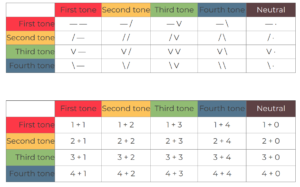

Fortunately, there is a good solution to 90% of these problems: Tone pairs. A tone pair is simply a combination of two tones, usually in a two-syllable word. Most words in Mandarin have two syllables, so finding examples is not hard. Since there are four basic tones and a neutral tone, there are 20 possible combinations of tones (the neutral tone can only appear on the second syllable of a word), and therefore 20 tone pairs to learn.

So how do you use tone pairs? You learn one word for each pair (see below) and you practise it to literal perfection. You should be able to say that single word correctly every time. This will take some time to achieve, but it’s certainly easier than learning to say all words perfectly! Once you have learnt these twenty words, you can then mentally copy the tone pattern to other words you struggle with. Do you know how to say shuǐguǒ, “fruit”, but get kěyǐ, “can”, wrong? Say the words after each other repeatedly and you’ll be able to imprint the correct pattern from one to the other!

Below are 20 handpicked words you can use to learn all possible combinations of tones. The numbers refer to the tones, so 1 = first tone, 2 = second tone and so on. 0 means neutral tone. Click on the Pinyin to play audio. Please note that this content is covered in much greater detail here, including audio and video: Focusing on tone pairs to improve your Mandarin pronunciation.

In the article linked above, you can also find as many examples for each tone combination as you want!

Focusing on tone pairs to improve your Mandarin pronunciation

3.4 How to remember tones

An often neglected problem with tones is that to pronounce a word correctly, you need to remember what the correct tones are. If you don’t aim for the right target, you’re not going to hit it. A common response to this problem is that you should practise listening and speaking so much that the correct tones just feel right, but I think this is oversimplifying things too much. I have probably been listening to well over ten thousand hours of spoken Mandarin and I sometimes need to think about which tones a word has and only then am I able to pronounce it correctly.

So how do you remember the tones? A good method is to rely on one of the standard colour systems for tones described earlier in this article. You can then use standard mnemonic strategies to remember what tones a word has. Mnemonics are clever memory techniques that people have been using for thousands of years to memorise all sorts of things, but they work best with concrete objects, not abstract things like tones.

Thus, we peg each tone to a colour and an element and then use those to create associations or stories that allow us to recall the correct tones. You shouldn’t do this all the time, or you’ll spend too much time creating mnemonics, but it’s a great way to remember tones you keep forgetting. Here’s the pegging system I use:

- First tone – Fire (red) – Use a burning inferno as the setting for your associative chain.

- Second tone – Light (yellow) – Incorporate dazzling light in the background of your mnemonic.

- Third tone – Plants (green) – Place your story in a verdant jungle.

- Fourth tone – Blue (water) – Let your story take place underwater.

Read more about how to do this in practice here: Extending mnemonics: Tones and pronunciation.

3.5 Identifying and fixing problems with tones

Regardless of how diligent or talented you are, you will at some point realise that you have a problem of some sort related to tones. Maybe you misunderstood how the third tone is supposed to be pronounced (like I did), or it’s something more subtle. How do you identify such problems? And how do you fix them?

First and foremost, it’s hard to fix a problem you aren’t aware of, so identifying the problem in the first place is already halfway to a solution. Most students are not aware of how good (or bad) their pronunciation is and don’t know what they should work on either. There are many different problems related to tones and they all have different solutions. Here’s a quick overview of the most common ones:

- Not hearing the tones

- Not being able to produce basic tones

- Not remembering the correct tone

- Not being able to produce tones in demanding contexts

- Not being aware of phonological rules

- Mixing up tones and intonation

- Falling back into old habits

It should be clear that depending on what the problem is, a different solution is required. If you don’t remember the correct tones for the words you’re saying, no amount of speaking practice will help you improve. If your problem is that you’re not aware of phonological rules, learning a bit of theory might be necessary to start paying attention to the relevant tone changes. I wrote more about these seven kinds of tone problems here.

To figure out what your problem is, both in general and more specific, you need feedback, preferably from a professional teacher. As mentioned before, I offer comprehensive feedback on your pronunciation as an add-on to my pronunciation course, but the important thing is that you get feedback, the earlier the better.

There is a clever method to figure out problems with tones, that is completely free to use, however. If you have studied Mandarin for a while and want a reality check on how good your tones are, try the following exercise:

Print the table in this article (shown on the right).

Print the table in this article (shown on the right).- Randomly select ten combinations and write them down on a piece of paper without showing anyone.

- Choose any syllable you like, such as yi or ma, and pronounce each of the combinations using only this syllable. For example, if the combination is third tone + second tone, say yǐyí or mǎmá.

- Ask a native speaker to guess what combination you are saying. If you say yǐyí or mǎmá, she should point at the 3 +2 cell in the table. You might need to explain what you’re doing for this to work.

- Go through all the combinations and see how many she will guess correctly! If you’re very serious, go through all combinations more than once, preferably with different native speakers.

- Do the reverse and have your native-speaking friend pronounce various combinations to see how well you can identify them.

This is a form of minimal pair bingo, and I have described the process and why it’s useful in the article linked below. If you are a beginner, you can use this test, but with only one row or column at a time! This exercise is harder than most students think, so take it easy. A smart method to discover problems with Mandarin sounds and tones.

A smart method to discover problems with Mandarin sounds and tones

3.6 Questions and Answers about tones

Below, I have collected some common questions about learning tones in Mandarin that I haven’t brought up in other parts of this article. If you have a question that isn’t answered in this article, please leave a comment below!

- I’m [age], am I too old to learn tones? No, you’re not too old. I’ve taught many students in their 60s and 70s and they were able to learn tones. So will you. Learning tones becomes harder the older you get, so the best time to start is in the womb, but the next best time to do it is now. There is no sharp cut-off point where learning new speech sounds becomes impossible, but delaying certainly won’t make it easier. So, no, you might be too busy or too lazy to put in the effort to learn Mandarin, but you’re not too old!

- Does using colours make it easier to learn tones? It probably doesn’t make it easier to hear and say tones, but it can make it easier to remember them and more practical to study them. I covered how to use colours to remember tones earlier, and colours can also make it easier to see tones. It also enables you to include tone information without Pinyin, which can be beneficial. I wrote more about the pros and cons of using colours here: Does using colour to represent Mandarin tones make them easier to learn?

- Is musical aptitude necessary to learn tones? No, but it might make it easier to perceive and pronounce tones initially. Tones in Mandarin are different from musical tones because they are relative. The first tone is higher than the third tone, but it’s not at an absolute pitch height. It’s about contours, how pitch changes over a syllable, such as falling or rising, not about hitting a specific note. You can be tone-deaf and still speak perfect Mandarin, and Chinese people don’t all have perfect pitch.

- How do tones work in music? A follow-up to the previous question is that if both music and tones are about pitch height, how do you combine them? The simple answer is that you don’t and that most songs in Mandarin simply ignore tones. This makes them harder to understand, but as we have discussed above, it’s often possible to understand anyway based on context. I discussed this more in a student Q&A podcast episode (#178).

- What are the best resources for learning tones? That’s a great question! There are many resources available to help you learn tones, but as we have seen, you can get far with a media player and a microphone. Of course, you do need something to mimic, and other tools might be helpful too, so let’s move on to the next section.

4. Resources for learning tones

There are many resources for learning tones and this list is not meant to be exhaustive. Please refer to Hacking Chinese Resources for a full list (just search for “tones”). If a significant resource is missing there, please let me know and I will consider adding it!

4.1 More guidance from me

If you want to learn more about learning Mandarin from me, I have two courses that are relevant here:

- Hacking Chinese Pronunciation: Speaking with Confidence is a full video course where I teach you everything you need to know about Mandarin pronunciation. As mentioned, there is also a feedback option if you want to either get feedback as you learn (beginners) or a thorough, systematic check-up of how far you’ve come (more advanced students).

- Unlocking Chinese: The Ultimate Guide for Beginners covers everything you need to know about learning Mandarin as a beginner, including pronunciation and tones. If you want to dig deep, you should check out the pronunciation course instead, which works for both beginners and more advanced students.

4.2 Online tools and apps

There are digital tools and software that can help you with specific aspects of learning tones in Mandarin. Here are my favourites:

- The Hacking Chinese free tone training course was created by myself and Kevin Bullaoughey over at WordSwing for a research project. It helps you learn to identify the tones correctly. It’s great if you struggle with the basic tones, but is limited in that it only covers single tones, not tone pairs or tones in phrases and sentences.

- Mandarin to IPA Translator allows you to annotate a text in Chinese characters with IPA (the International Phonetic Alphabet). This can be helpful if you already know IPA, but if you don’t know it already, I suggest that you learn the basics first. This is included in my pronunciation course, but you can also check out Wikipedia or AllSet Learning Chinese Pronunciation Wiki.

- Talking Chinese to Pinyin/Zhuyin Converter is a tool for annotating text with either Pinyin or Zhuyin. You can also choose to only add tone marks, which is great if you want to focus on tones without being distracted by Pinyin. You can also add colours if you want. The tool is provided by Purple Culture, and they offer lots of other nifty tools, mostly for free. For more about learning Pinyin, Zhuyin and other transcription systems, please read the series starting here: Learning to pronounce Mandarin with Pinyin, Zhuyin and IPA: Part 1

- Praat: doing phonetics by computer is a freely available tool for phonetic analysis. It’s designed for researchers and other people with a keen interest in acoustic phonetics, so don’t expect a modern interface and a user-friendly experience. If you take the time to learn the program, though, it’s great! I’ve spent hundreds of hours with Praat,!

Learning to pronounce Mandarin with Pinyin, Zhuyin and IPA: Part 1

4.3 Sound and tone references

Mandarin only has a bit over 400 unique syllables, and if you include tones, the number is about three times that. This is limited enough to present in a single, comprehensive chart. These charts allow you to click any syllable and hear it spoken with any tone. Here are my favourites:

- Chinese Pronunciation Wiki Pinyin Chart (AlSet Learning)

- Mandarin Chinese Pinyin Chart with Audio (Yabla)

4.4 More about Mandarin pronunciation

If you want to read up on Mandarin pronunciation, phonetics and phonology, here are two books in English that I recommend:

- Lin, Y. H. (2007). The Sounds of Chinese with Audio CD (Vol. 1). Cambridge University Press. This is an introduction to Mandarin phonetics and should be readable for the average student. The author describes all sounds and tones and does a decent job of doing so in a pedagogical manner.

- Duanmu, S. (2007). The phonology of standard Chinese. Oxford University Press. If you already have a foundation in phonology and want to read up on the phonology of Mandarin (Standard Chinese), this is the best book I know. Be warned that without some knowledge of phonology, this book will be hard to understand.

For references in Chinese, check:

- 王理嘉、林燾. (2013). 語音學教程. 五南出版社.

- 朱川. (2013). 外國學生漢語語音學習對策(增訂本). 新學林出版社.

There are also some good resources online, some of which I have mentioned already:

- Standard Chinese phonology on Wikipedia

- Mandarin Chinese Phonetics by Ptatrick Hassel Zein

- AllSet Learning Chinese Pronunciation Wiki

I collected some more resources for improving your Mandarin pronunciation here: 24 great resources for improving your Mandarin pronunciation.

24 great resources for improving your Mandarin pronunciation

Conclusion

Puh, that was one of the longest articles on Hacking Chinese! I hope that you have found this guide helpful,! If you’ve read this far, either because you read through the whole article, or because you read what was relevant to you and then scrolled here, please leave a comment below to let me know what you think! Was the guide helpful? Do you still have questions after reading it? Or do you perhaps have some suggestions or recommendations?

Editor’s note: This article, originally published in 2018, was rewritten from scratch and massively updated in February, 2024.

First tone

First tone

Third tone

Third tone

Fourth tone

Fourth tone

7 comments

Excellent article. Our Hanping Chinese Dictionary app has a soundboard section to help with tones. Rather than the common approach of laying out the pinyin table as initial-final combo, it asks the user to first select an initial or final and then presents a table of all corresponding syllable-tone combos. This way, you can really drill down into learning, say, one initial in all its various forms. Furthermore, you are only given sounds that actually exist (1298 single-syllable sounds in total). Also supports Zhuyin.

The Pro version additionally includes the ability (HSK Tone Pairs tab) to hear two-syllable sounds from HSK level 1 to 5. Note: if you have purchased the HSK (2 to 5) add-on, all tone-pairs are available, otherwise only the tone pairs in HSK 1 are available.

Lite: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.embermitre.hanping.app.lite

Pro: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.embermitre.hanping.app.pro

I’ll need to revisit these function in Hanping again. I haven’t checked anything out since you released the sound box, which was great. Thanks for reminding me!

I learned tones with a spectrograph. I was initially unable to even differentiate the tone of my own speech, but after many hours with a spectrograph, I could hear and reproduce tones.

I agree that tones are absolutely critical to learn. But I would say that the hardest thing about learning tones is keeping one’s motivation up during the learning process. Memorizing tones can feel really boring and dry.

I found this game “Ka Chinese Tones” https://chinesetones.app/ that was helpful in mastering tones that I now recommend to all my friends trying to learn Chinese. It was easy to use, and after using it for a while, it made tones feel very natural for me.

There is a broken link for the audio file in this article’s section 3.3 for:

3+4 mǐfàn, rice

You may want to correct it.

Thank you for pointing this out, I’ve now fixed the error!

This post really clarifies the often confusing topic of Mandarin tones! I appreciate the tips on practicing and the examples provided. I can already see how focusing on tones will improve my speaking skills. Thanks for sharing such valuable insights!